I first met the director Barrie Kosky when he wrote me asking if I would help him conceive of a spectacular pageant to open the 2026 Gay Games, an LGBTQ+ sporting event that, at the time, the city of Munich was vying to host. Kosky had been engaged to develop the opening ceremonies if Munich won.

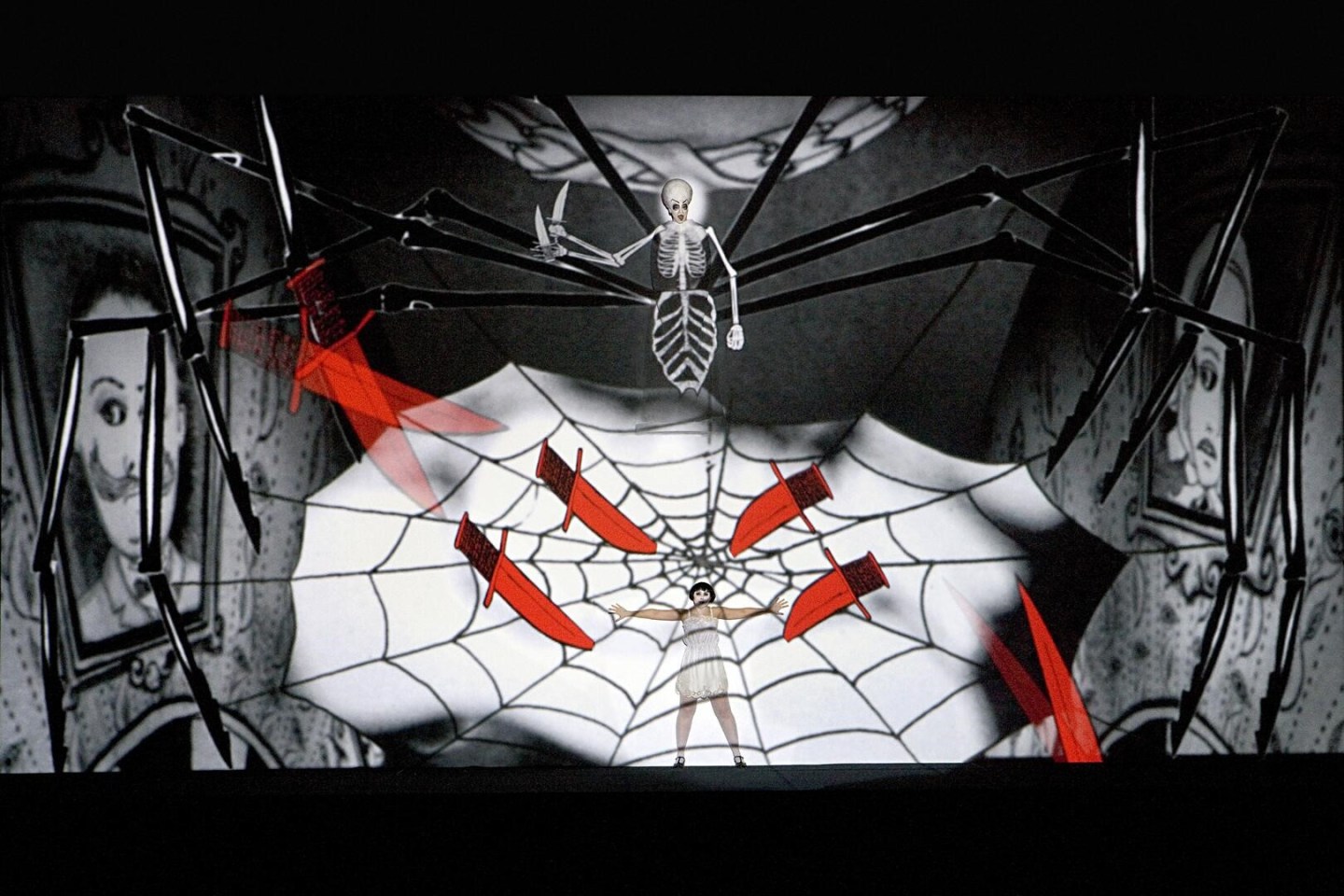

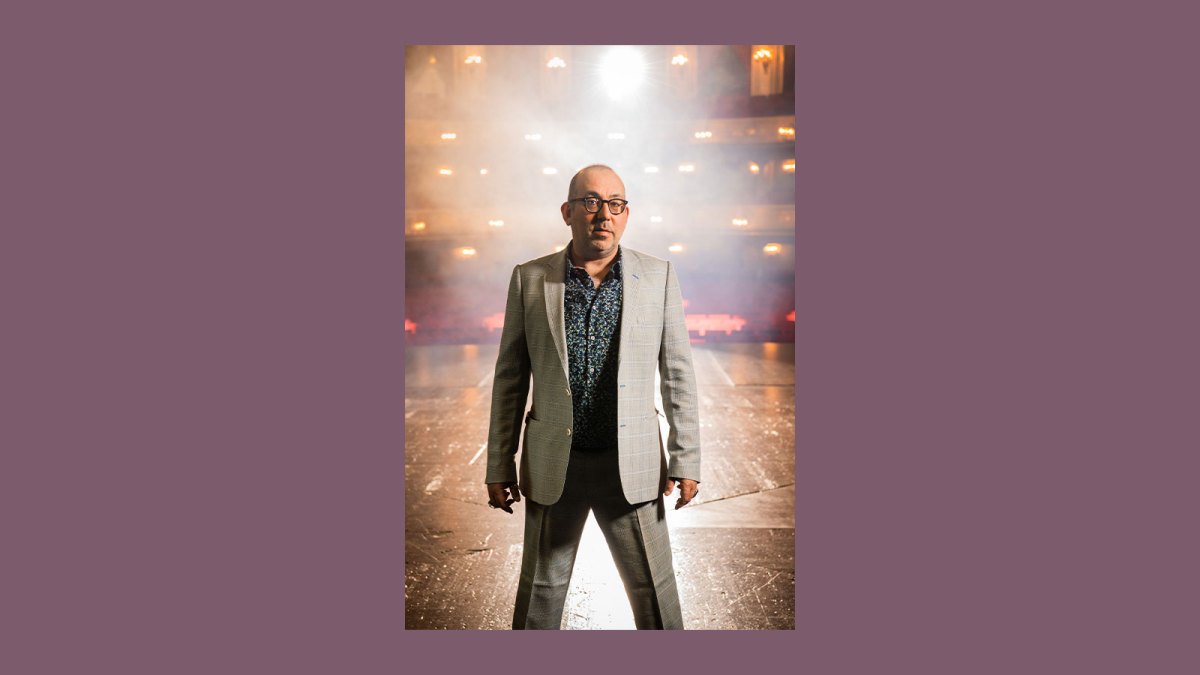

That Munich’s bid was unsuccessful means the world will never see the performance we were just beginning to sketch out with the artist Liz Rosenfeld and the literature professor Elahe Haschemi Yekani; a fever dream of the troubled history of German queer life with tap-dancing Leni Riefenstahls and at least one appearance by Ludwig II. Since then we’ve become friends. We sat down in a cafe in our neighborhood (with Kosky’s omnipresent Goldendoodle/German Hound mix, Sammy, bouncing about our feet) to discuss Kosky’s tenure at the Komische Oper (which began in 2012 and which is ending this summer with a new production called “Barrie Kosky’s All-Singing, All-Dancing Yiddish Revue”), the need for more rehearsals in opera, life as a diaspora Jew in Germany, and being attacked by priests at Bayreuth.

VAN: Your time at the Komische Oper is generally considered to have been a successful one. Why do you think that is?

Barrie Kosky: I mean, I’m very glad that it was successful. What does success mean? How do you measure ten years? Because not every production can be successful. So you have flops, and you have successes, and you have a whole spectrum of very subjective judgments. I like to measure success in three areas. And that is, firstly, what the artists think. Do artists like being in my house? Do artists like coming back? Do artists feel respected and challenged? This is my first criteria because I’m an artist as well as an administrator. Secondly, I judge it by the audience. And I don’t mean just box office, because before COVID, we had a 92 percent box office. Now, it’s up and down, but it’s probably about 80 percent, which is still pretty good. People want to see operettas at the moment; they want to be entertained. They don’t want dark pieces right now.

But back to the last ten years: Success for me isn’t that we can sell out 92 percent of the house, it’s that we can sell out a run of Schoenberg’s “Moses und Aron.” That’s success in an audience. Our audience is loyal. They come back. They are stimulated and entertained at the same time. The third thing, the thing that I’m the most proud of, is that we have become a family. Every theater production has to be a family, a family you choose to be with as opposed to the family that you are born with. And I know that we have a very special spirit there, offstage in the Komische Oper. That does not happen by accident. We tapped into two big sources that made sense for the house: the Metropol theater and the Berlin operetta tradition, which had been abandoned, and the music theater of Walter Felsenstein.

Was that something you knew when you took the job, that you’d turn the house towards the two poles of Felsenstein, who founded the house under the auspices of the East German regime to bring opera to the masses as populist music theater, and Berlin operetta?

When I took the job, I had no idea what the Metropol theater was! I was wondering what the theater was before the war and my dramaturge started doing research and Jesus fucking Christ! Why hadn’t anyone done anything with this before? This was the leading German operetta house, the place where Tauber, Massary, Abraham, and Kallmann conducted and performed. It was an amazing venue up until 1933. What jewels were buried there? And we found them! “Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will,” “Roxy und ihr Wunderteam,” this whole Berlin operetta tradition that we brought back stemmed from that research.

And then there was Walter Felsenstein’s philosophy of music theater. That man radically changed everything we know about the opera. Not just because of his pupils Götz Friedrich and Harry Kupfer, but because he brought Konstantin Stanislavski [whose eponymous technique laid the groundwork for Method acting—Ed.] into the opera house at the Komische in the 1950s. So that building is the mothership of music theater. Even though in my work there is no aesthetic relationship to Walter Felsenstein, I think we tapped into the spirit of Felsenstein. This is the only opera house in the world founded by a director to be a laboratory of a particular kind of theater.

So that was the ten years: juxtaposing serious music theater—“Moses und Aron,” Mozart, Baroque pieces—with this tradition of Berlin operetta. And the day I was most proud of was in 2015 when I looked at the Spielplan [performance calendar] and I saw Wednesday night: “Moses und Aron,” sold out; Thursday night: “West Side Story,” sold out; Friday night: “Don Giovanni,” sold out. All performed by the same orchestra with some of the same singers and chorus people. And I thought, That’s unique.

To do it, I had to make it my house, to infect everyone with the Kosky style. The programming was just a reflection of my way of working, which is based on respect, humor, enjoyment, and love. And realizing that it’s a privilege to work in the opera in the 21st century, to be paid by the taxpayer. There is no entitlement: You have to earn the respect of the audience, with respect and loyalty and joy and virtuosity on the stage. Which I demanded.

I told the chorus: “I know you have a reputation for being extraordinary actors since the Felsenstein days. I want to see it every night.” And the same with the orchestra, the flexibility is amazing. Schoenberg one night, then Bernstein, then Mozart. I told them: “This is your identity, it’s important that you are proud of this.” I want an audience seeing a third revival of a five-year-old production of mine on a Wednesday that’s better than it was at the premiere. That’s our job. And I think that comes across when you sit in your seat in that house, and realize it feels different because every single person on that stage knows why they’re there and what they’re doing, which is not the case in most opera theaters.

Is that lack of intention why most opera productions are—provocatively asked—so bad, at least from a theatrical point of view? The musical standards are high in all the major houses, but dramatically it’s so often a disaster.

I’ll tell you the difference we had: It’s practical. The Komische Oper has a minimum of three weeks of revival rehearsals for any production. A minimum. Even if it’s the same cast as last year. You do three weeks of rehearsals, not three days. I rest my case.

When you work in a house like Vienna or Munich, where I love working, you get spectacular casts. And, frankly, my productions are so complicated you need two or three weeks of rehearsal to get them on stage. I make my productions deliberately quite complicated in part for that reason. But it’s a different way of working, and I understand why these companies do it, but it makes a huge difference: These companies do 40 titles a year sometimes. It’s so difficult to get stage time. At the Komische, we wanted to make sure the audience would see something great on stage, not thrown on. We may not have the most famous singers in the world, but we have music theater.

As a director and Intendant [artistic director] I always prefer the singer who is spectacular on stage to the singer who has the most perfect voice. A beautiful voice is subjective, and it can be detrimental to the theatrical evening. The definition of a beautiful voice changes—the beloved voices of the 1960s are different to those of the 1920s, and are different to those now. The Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin is one of my favorite singers, and today he probably wouldn’t find work the way he sings… it’s incredibly expressive, almost screaming. Other houses have other priorities, and I respect those priorities. Not every house has to work this way. But any successful opera company is successful because it’s authentic to its history and identity. I think when you pretend to be something you’re not, it’s ridiculous. If I suddenly put Jonas Kaufmann or Anja Harteros on the stage of the Komische Oper, it would be ridiculous. They don’t belong there, and they have other places to be. You have to understand what the house is.

You say this isn’t the way everyone needs to work, but to me it seems like a repertory company focused on theater and building deep relationships to its audience is more sustainable in every way—in terms of money, in terms of carbon—than the star-driven model a lot of other houses are still stuck on.

We’re certainly coming to the end of a chapter in opera where singers could sell out a house. That doesn’t happen anymore. But I do think it’s scandalous that journalists still say “opera is dead.” Hang on a moment. Before COVID we were selling 220,000 tickets a year at the Komische Oper, 700,000 a year [between the three major opera houses] in Berlin. You cannot tell me that it’s dead. You cannot tell me when our average audience age is 49 that opera is a dead form. You cannot tell me that the 40,000 schoolchildren a year coming to the Komische Oper are not interested in the form. The idea that opera is irrelevant comes from the Anglophone world. I roll my eyes when people say that sort of thing.

It’s just as ridiculous as saying Regietheater killed opera. First of all there is no such thing as Regietheater, because theater is collaborative—I collaborate with a conductor, designers, singers. And the biggest problem with a lot of productions is not the director, it’s that there aren’t enough rehearsals! The conductors come in at the last moment. There are glorious exceptions—people I love working with like Vladimir Jurowski, and Emmanuelle Haïm, and Philippe Jordan, and Jakub Hrůša, are fantastic conductors who take their theater work very seriously.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

I think the future is about seeing what models work. We know rehearsal time brings great results, we know that less is more, maybe there’s just too much put on. Maybe we should step back a little bit and ask, How do we allow the conductors enough time with the orchestra? In the repertoire, that the directors get enough time for revivals? That the singers are in rehearsal for the whole time and not just parachuted in for the last week of rehearsal? I won’t say any names, but I’m always annoyed when singers announce they’ll be away for half the rehearsals because they have a concert here and a concert there so the agents can make as much money as possible. Now, I say No. Of course, people have holidays and days off, but I spend three to four years working on these productions. They cost millions in taxpayer money. People are coming to see them and paying exorbitant prices. I’m not going to be so cavalier with rehearsals. People are expecting something really good and should demand it, and the only way to do that is to have rehearsal time. I have to fight for it.

We have to get away from the whole idea that we’re competing with film and TV. Livestreams are fun, but as far as I’m concerned they’re just a marketing tool. I think we have to encourage people towards that basic human desire to sit in a dark room with 1,000 or 2,000 strangers and watch an unamplified voice perform a ritualistic evening of psychology, narrative, and images which leads us back to the ancient Greek theater and which is the best experience you’re going to have outside a religious institution. This is shamanic ritual. Nothing compares to the real event. It’s not elitist. It’s not indulgent. It’s not irrelevant. It’s a dream place. Outside of religious institutions we don’t have many places where you are deliberately not confronted with your daily life. I don’t want to go to the opera to see daily life, I want to go into my subconscious and to go into other worlds, other cosmos. The human voice is the single most potent instrument ever invented. It comes from muscle and air in a human body, and we still don’t know the mystery of how it’s created. And at the end, it links us to the natural, animal and spiritual world.

What are your regrets about the last ten years?

Two big ones: First I wanted, when I got the job, to establish a historical-instrument Baroque ensemble within our orchestra. Like in Zurich. With Baroque instruments and bows. Because no German house has that. In the spirit of the house, to have it actually in the house. At that stage, I don’t know if I had the trust with the orchestra. There were some people who really wanted to do it and we organized some concerts, but I didn’t want to force it on them. I would have loved to leave them with a fantastic Baroque ensemble. At that time they were more interested in some idea of the deutsche Klang [the German sound], which I’ve never understood exactly what that’s supposed to mean. This orchestra is not going to play “Tristan” like the Staatskapelle, its identity is virtuosic diversity.

My other regret is I never found a composer to do a world premiere operetta that could redefine that form for the 21st century. I looked everywhere but never found the right person I could collaborate with on it.

You’re ending your time at the Komische Oper with a new show called “Barrie Kosky’s All-Singing, All-Dancing Yiddish Revue.” Your Jewish identity has been a very public and prominent part of your artistic life. How did it shape your time at the Komische Oper and why did it feel important to end this way?

Well, you know as well as anybody, the diaspora Jewish experience is incredibly complicated, it has many different voices and as many different experiences. I came back as someone who had no German-Jewish family, my family did not come from Germany, like a lot of my German-Jewish friends. So I’m coming as a diaspora polyglot back to Berlin, which puts me in the position of loving the culture but also being able to stand outside it, to look at it and ask, What are the issues or problems here? I found when I arrived here, after five years in Vienna, wondering why audiences there and here had a hard time understanding Jewish art and projects that were not about the Holocaust. Germans and Austrians don’t associate Jewish culture with anything but the Shoah or Israel. I thought it was a cliché but then I realized, my God, it’s true. It’s either an Auschwitz inmate or an Israeli soldier. That is really the mainstream understanding of Jewishness. And I thought: It can’t be, I must be wrong. And then I realized I was spectacularly right.

What is astonishing to me is that there are huge gaps in the German understanding not only of Jewish culture, but of Jewish culture within German culture, which it is. It is a part of German culture, it is not a separate adjunct. We know that the whole of the 19th century was this tango between conflicting forces, which contributed to amazing things, and terrible things in the 20th century. And I’ve always been fascinated by that battle between light and darkness. A lot of Germans don’t really want to look at the Jewishness of Heinrich Heine, or the Jewishness of Franz Kafka.

At the Komische, I started down this path with “Ball im Savoy,” as part of bringing back the Berlin operetta tradition which was so shaped by Jewish creative voices. It was written in 1932. I didn’t set it in Nazi times, I set it in a fantasy jazz world. I thought, This is a fantastic music theater piece. It’s one of the last operettas of the Weimar Republic. I wanted to stage it right, not ending with some giant swastika and everyone being marched into the gas chambers and the audience going, Oh, God. But I realized I couldn’t present it without some context. So I made two decisions: I added a duet between two servants in the third act, a duet from another Abraham operetta, and we did that in Yiddish. And on opening night: I have never heard silence like that in a theater. Anywhere. They danced a beautiful waltz and I thought, I don’t have to say anything.

At the end of the show I did my second thing: We do an encore, after the bows, of Paul Abraham’s famous song “Good Night,” and I said to the audience from the stage—and Dagmar Manzel, who stars in the show, has said this speech instead of me for the last ten years: “Paul Abraham had to leave Berlin in 1933. Abraham stood in this pit right here, and was an important part of Berlin, and we are singing ‘Good Night,’ and as we stand here singing we are releasing his dybbuk.”

Talk about not hearing a pin drop during the duet. They finished singing a cappella. The dybbuk was released. The audience did not applaud for at least 15 seconds, there was complete and utter silence. And that followed three hours of ecstatic joy. I think that said clearly what I was trying to do. To say: I’m doing this music because it’s fantastic art. I want these people to be remembered not because the Nazis did something horrible to them but because they were great artists and part of your culture. Stop exorcizing it out of your culture as if it’s something that’s not part of you. Be proud of it. I give you permission to enjoy it and love it and own it. This is part of the problem: that you’re not owning it. I don’t want people to buy a ticket to go see some entartete [degenerate] operetta. I don’t want that to be the memory of the piece. I want people to think: This was fabulous! Thank goodness the Nazis didn’t win.

What about the more general political climate in Germany around Jewish identity?

The Shoah left a national trauma on both Germany and Israel. Would Israel have happened if the Shoah hadn’t happened? I don’t know. It’s hard to say. But it certainly accelerated the process. Lots of stuff was swept under the rug. It ended all of the other Jewish political possibilities. Many Jews, as you know, were not Zionists. After the Shoah, it happened. And we are now seeing the results of that decision.

We know, you and I, that this relationship between Germans and Jews and German culture and Jewish culture and German culture and Israeli culture, is a labyrinth of quite complicated issues. However, in 2022, there are a number of things that are not complicated. It’s very easy to say the facts are the facts. What successive Israeli governments are doing in the West Bank and Gaza is wrong, full stop. That should be a fact, whether you’re a Zionist or nationalist Israeli or Orthodox Jew or whatever. A fact. It’s wrong. Something has to be done to stop it. And it doesn’t help when the attitude from most German and Jewish organizations in Germany is that Israel can do no wrong and any criticism of Israel is anti-Semitic. This has to change because it is going to be disastrous for Germany and spectacularly disastrous for Jews. It is the responsibility of the diaspora and diaspora voices to offer the Germans alternatives to the propaganda put out by various Israeli governments. I love Israel. I have Israeli friends. Do I want Israel as a country? Yes. Do I want the Palestinians to have a country? Yes. Do I want two countries there? Yes. Share the land.

What is not celebrated in Germany enough is the diversity of Jewish voices. This has to change. For every Jewish person saying Israel can do no wrong, there’s another one saying Oh yes they can, and I know both you and I could give any German a list of very intelligent anti-Zionist academics, artists, and political thinkers that are Jewish.

And the Germans are astonishingly quick to call anyone an anti-Semite—even the Jews! And then you get dragged through the media as an anti-Semite and then worry: Am I eligible for grants? Am I eligible for jobs? For the funding we live off in the arts?

It’s terrifying. And I would say: Well, what can I do? I can’t just sit in a cafe and complain. Now that I’m leaving the Komische Oper, becoming a freelance artist and no longer responsible for the institution, I can say a lot of things I couldn’t before. I think it’s the responsibility of people like you and me to educate the Germans. We have to explain what is happening here: that the German conscience is being manipulated sometimes by Israel in order to not allow contradictory voices to appear. I don’t think the Germans understand how grotesque it is that a non-Jewish German can label a Jew anti-Semitic. I think people are very confused and nervous, which is potentially disastrous. I think the whole education of Germans about their past needs to change. You can’t keep separating the Jewish elements from the rest of it. You can’t say in the 21st century that Islamophobia and homophobia are not as important as anti-Semitism. If you hate anyone, it doesn’t matter if it’s because they’re a Jew, or Muslim, or a gay man, or a trans man. Hate is hate. And let’s face it: Being a Jew in Germany is not as hard as being a Muslim. A white Jew does not have the same problems as an immigrant Muslim in Germany in the 21st century. And when most of the anti-Semitic acts are committed by white German nationalists, where’s that discussion?

We have to get rid of this idea that the Germans dream of, where it’s all going back to the 1920s and there’s going to be this huge Jewish culture here in Germany. Of course there are Jews doing fantastic work all over this country, but just because some Israelis come to Berlin to go to Berghain on the weekend does not mean that there’s a renaissance of Jewish culture here.

And often those people who come are on the one hand celebrated as part of that supposed renaissance and on the other hand silenced or ignored when they are not, as they often are not, supportive of the official Israeli state line.

The problem is that one of the great joys, up until very recently, of the Jewish diaspora and Jewish-Israeli culture has been this smorgasbord, this buffet of voices: secular voices against religious voices and reform voices against ultra-religious orthodox voices; communist atheists arguing with right-wing religious people. This is part of Judaism, this Talmudic metaphor, the best thing the Jews ever gave us, that in every page there is more than one truth and the work is figuring out conflicting arguments about a text. Could there be a better metaphor for life?

Unfortunately, the German world does not hear enough of these voices. So what happens? The first person quoted in the article is the Antisemitismusbeauftragter [an official, usually from the state, tasked with the prevention of anti-Semitism], who is likely not Jewish, and very likely has a specific political agenda. And the second quote is from the Zentralrat [the Central Council of Jews in Germany], which shares that agenda. And I think: No one called me! No one asked the Israeli professor at one of the universities here who would likely have a completely contradictory attitude to what was published in the first paragraph. So this idea of the Jewish expert voice has to be broadened. There are spectacularly brilliant Jewish writers and thinkers in Germany who have the complete opposite opinion of the Antisemitismusbeauftragter and the Zentralrat, which is as it should be. I’m not denying that theirs is an important perspective, but there are also other voices. And I think the German media are fixated on them because they like authority, they like the idea that there’s one person or organization who speaks for all Jews, because it’s easier than trying to wade through and figure it out. But [the German media] have to.

You were the first Jewish director to work at the Bayreuth festival, with a production of “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.” In 2021, the production, which dealt with anti-Semitism, had its last run of performances. How did that feel?

It was a really important project for me, artistically and personally. I exorcized my Wagner demons from my body and soul, which was very healthy. A lot of people didn’t like the production, but the majority were so supportive—I met people who saw it ten times. At the last show, I was talking to a group of French journalists at the first interval and suddenly, down from the top of the Grüne Hugel, we see three priests walking towards us in cassocks. It looked like something out of a Pasolini film: three priests with short hair and crucifixes and cassocks. Now your first reaction as a gay Jewish man is to go, Oh my God, faygelachs! Here are three faygelach Catholic priests, how brilliant. And the French journalists were laughing, saying, “Guess you’ve got fans in the Catholic Church.” And then one of [the priests] spun off and started walking towards me. As he got closer I realized he wasn’t giving off a good energy. He walked up to me—and this was mid-pandemic, and with no distance—he jabbed his finger in my face and said, “I just want you to know how much I hate your production.” With a look in his eyes that was like two thousand years of Jew-hate. My first reaction was shock, and in my shock he turned around and walked away. And I shouted after him, “Excuse me, how dare you speak to me like that, come back here.” And then he turned around and said to me, “And you know why.”

I said, “No, I don’t know why.” The French journalists told me that the uniform indicated the priests were in some very conservative sect. And then I thought: My God, if he hates it now, he’s going to really hate the second act. After the second interval he came back. Talk about the moth to the flame. And this time I was prepared for action. He came towards me again, and I asked, “Have you got anything to say?” And he just stood in front of me for ten seconds and didn’t say anything. I thought, “You’re meshuggah, not only are you a racist, faygelach Catholic priest, you’re meshuggah.” He turned around and walked away, and I said “Excuse me, I think your behavior is outrageous. If you’re going to come up to me like that, I think we should at least engage in some conversation.” And he held up his hand and said nothing. And then I started shouting, loudly, around all these people with their champagne, “Shanda! Shanda!” The last thing I screamed was “shanda” as he walked away. I couldn’t have asked for a more fitting conclusion to my time at Bayreuth than to be abused by a Catholic priest. My theory is: Always provoke, with irony and humor. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.