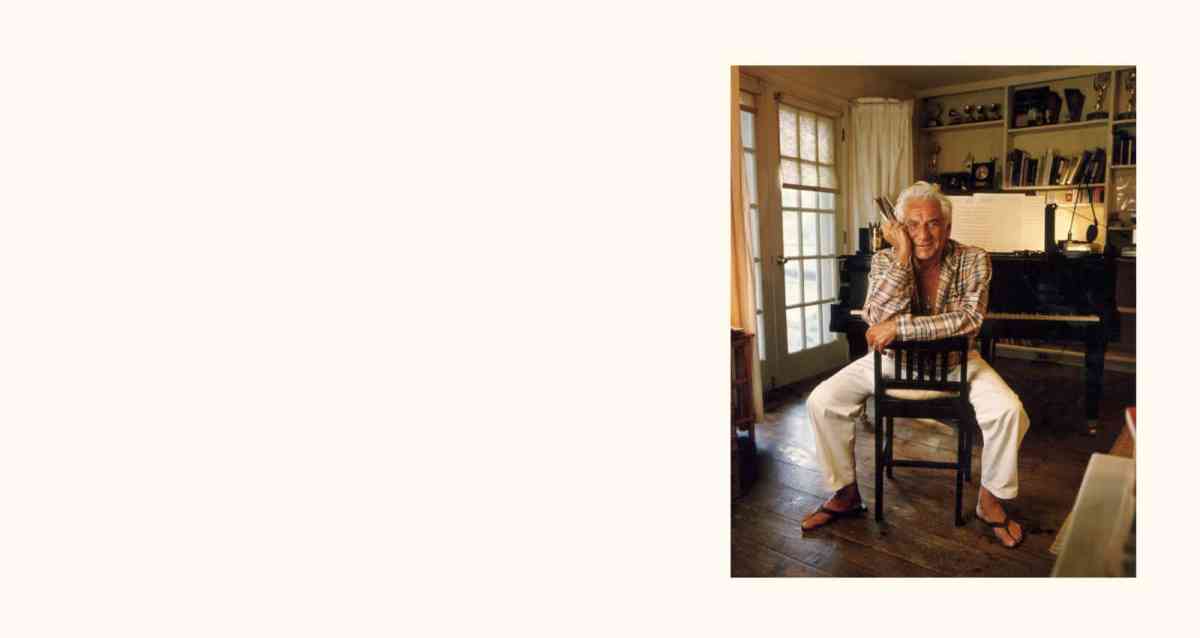

On an unusually sunny February afternoon, I met Craig Urquhart in his apartment at Berlin’s Nollendorfplatz, the beating heart of the city’s gay life. (Christopher Isherwood once rented a place here.) “I’m going to be very bad and have a gin,” Urquhart said, but then realized he didn’t have any ice. Urquhart was a longtime assistant of Leonard Bernstein; he now works as a composer and Senior Consultant for Press and Promotion at The Leonard Bernstein Office. In the centenary year of Bernstein’s birth, Urquhart remembered his boss and mentor.

VAN: I was just listening to a piece Leonard Bernstein wrote for you, from his piano collection “Thirteen Anniversaries.”

Craig Urquhart: Lenny was famous for writing little pieces for his friends and colleagues for their birthdays, wedding anniversaries, these kinds of things. I wrote him a piece for his birthday in 1986, then on my birthday I got a piece of music—five bars, which were inserted into the piece that I wrote to him. That’s how we got started writing music for each other.

On Thanksgiving of 1986, he called me into his studio and he played this piece of music for me. He said, “What do you think of this?” I said, “I think it’s delightful.” And he said, “Well, it’s for you.” The manuscript says, “For Craig with thanks.” It’s a very sweet little piece, I like it a lot.

Does the music capture something about you?

In a way. There are two sides in the music. There’s the sort of allegretto part, where I’m moving around, because I’m working for him and my job is to keep things in order. And there are the little slow chordal moments that show the caring and the love…all this in, what, one minute? It was always a wonderful gift to receive from him.

The last 15 seconds or so are melancholic in a way that really surprised me the first time I heard the piece.

There’s a melancholic side to me. He probably picked up on that too.

Did you ever talk to Bernstein about Tom Wolfe’s article “Radical Chic”?

First of all, the truth about that is all out there. It wasn’t Bernstein’s party, it was his wife’s. And it was not to support the Black Panthers, but to support their right to legal defense. Tom Wolfe crashed the party and wrote this nasty little piece in an attempt to further his career at the cost of facts, I would say. It caused a lot of pain to the Bernsteins. They weren’t limousine liberals—they were really, honest-to-God, caring people.

I’ve talked to other people who were at that event. They said it was interesting because at first it was very awkward, and then people got to talk and it was a great way for people to get to understand the other side. But Tom Wolfe caused a lot of problems with his little “radical chic” thing.

Would you and Bernstein talk about politics, or just music?

You couldn’t separate music and politics with Bernstein. When I first met him, I was interviewed and there was a possibility of me working for him, but I just didn’t feel I was ready. I was very young, and I didn’t want to get into something I couldn’t handle.

Then at the end of ’85 his manager said he was looking for a new assistant. He had me talk to Lenny, and he asked me, “Why now?” It was because I learned he wasn’t what was portrayed in the press: this superstar dilettante. No. He was a very, very serious person, passionately committed to human rights, gay rights, the antiwar [movement]. He used his music to help push that agenda.

Leonard Bernstein, Symphony No. 2 “The Age of Anxiety”; Krystian Zimerman (Piano), Leonard Bernstein (Conductor), London Symphony Orchestra

Bernstein’s belief in music’s ability to heal was obviously deeply felt.

That’s what attracted me to him. You know, he believed in harmony, and he wrote tonal music, which is harmonic. He believed that music did have the power to bring people together, that it was a universal language. On Christmas Day in 1989, you had members of the four powers, the British, French, American and Soviets, plus Germans and a children’s choir from Dresden, all performing Beethoven’s Ninth together, the hymn of universal brotherhood. That was quite moving.

At the G20 summit in July 2017, Trump and Erdoğan listened to Beethoven’s Ninth together.

Well, that makes me sick.

Honestly, I doubt whether events like the four powers playing music together could change anything concretely in world politics.

We’ve changed. It’s a different world than it was 30 years ago.

Has music lost some of its power to heal?

I think certain pieces of music have become clichés—unfortunately, because they’re great pieces of music. Beethoven’s Ninth is one of them. They drag it out whenever they want to do something “profound.” It has lost its message when you have people like Trump and Erdoğan basically shitting on it.

Aren’t even they sharing in an experience of listening to the music?

It’s not the same as making it together.

You mentioned the Christmas Day concert in 1989. There’s a picture of you two at the Berlin Wall together on that day. What was that like?

It was a highly emotional time, especially for Bernstein and myself, because I loved Berlin and I’d been coming here by that time for maybe eight years, and the Wall had always been up and present. It was quite a thrilling year; you had this premonition that something was changing.

So this concert came about, and that morning was amazing: it was sunny in Berlin, which you know is rare, and, typically, for Christmas Day, it was very quiet. The only thing you could hear was people chipping away at the Wall. It was this background cacophony throughout the whole city.

Bernstein gave this profound, moving, incredibly emotional concert at the Schauspielhaus, which is now the Konzerthaus. The last head of the GDR, Egon Krenz, was present and gave Lenny the GDR cross. It had big medals and stuff, but Honecker had already given him one. He didn’t really need two…still, it was a nice gesture.

After the concert, and after the receptions, he said to me, “I’d like to go to the Wall.” I was with a friend of mine, he was with a friend of his. We just told the driver we’d like to go to the Wall. So he took us around; we went through Checkpoint Charlie and ended up behind the Reichstag. And Lenny went over and took a little hammer from this young kid, who’s alive and living in Berlin, and started chipping away at the Wall. It was a very private, intimate moment. It wasn’t like there were reporters or anything. He wanted to take pieces to his family, too.

Did you often spend time together outside of your professional relationship?

We both had our own private lives, we made a point of keeping them separate. I had the people who were important to me in my life, and they came along with me on tours sometimes, that kind of thing. He got to know my friends; he was a wonderful, generous person. But he also had his own private life, and I didn’t feel I needed to be involved in that at all. I was working for him on a professional level to make him function as Leonard Bernstein. I didn’t care what he did in his personal life, as long as it didn’t harm anybody.

I’ve come across rumors to the effect that if someone didn’t want to sleep with him, he would take action against their career.

No. That was never the case. He never was a predator at all. If anything it was the other way around. I saw many young people willing to do anything to be with the maestro. That turned him off. I don’t know anybody who would say that—unless they didn’t get something, didn’t get in the door. He was not that kind of person.

Did anything happen between the two of you?

[One time] he tried to kiss me, and I gave him a tap on the cheek and said, “Lenny, I’m not here for that.” And that was fine.

What was the musical work you were mainly handling for him?

Copying, liaising with librarians and soloists sometimes. He would mark his scores at night, and my job was to make sure his markings were ready for rehearsal. While he was having breakfast, I’d call the librarian or the orchestra. It was always last minute—kind of annoying sometimes.

Did Bernstein get stressed out in those situations?

He didn’t get stressed out. It was the other people around him, including myself. He just figured it was going to be done. And it was.

There was one time with the Chicago Symphony. He would not study the score. I had had the librarians ready from like 5 p.m., and I finally got the score to them at 2 or 3 a.m. Everything was ready for rehearsal; they were up all night. It wasn’t very nice, but he wasn’t trying to be mean.

Dmitri Shostakovich, Symphony No. 1 in F Minor Op. 10; Leonard Bernstein (Conductor), Chicago Symphony Orchestra, June 1988

It often takes a lot of behind-the-scenes scurrying to maintain the kind of spontaneity that many conductors like.

Yeah, but Lenny was a very disciplined person, he really was. He worked harder than most people I’ve met in my entire life.

Is it hard to be a composer and have had such a close relationship with a great composer?

He liked my music, supported it and encouraged me. It’s because of him that I write the kind of music I do. When I met him, I gave him some music, some beautiful, tonal music like I write today, and a big orchestra piece based on Stockhausen. He said, “You know, there’s only one real honest voice here. Are you gonna tell me which one?” And I told him the tonal one. He said, “Then that’s where you write from. You write from your heart.” He was also explaining to me his own dilemma: he wrote tonal music, which wasn’t very fashionable. Academia never took him seriously, though he wanted to be taken seriously as a composer. Now he is.

Is academia taking him seriously now?

I do think the fact that composers, even in academia and at universities, can write with a multiplicity of styles, is the Bernstein effect. Now the composers can use any kind of form or genre, it’s not the strict twelve-tone-system or the Boulez system. So I do think his influence is taken seriously. And there are a lot of dissertations on his music now.

Is the era of the great, Bernstein-style maestro over?

I think it’s a totally different world than it was back then. Those days are gone. That doesn’t mean some of the younger maestros aren’t great; it’s just a different way of going about it. The recording companies are not as wealthy as they used to be, the market is saturated. People don’t buy this stuff [he points to a large Bernstein box set on the side table] anymore, because it’s all done online. It’s fine—music is much more accessible in a way, and I’m a big fan of that.

Also I do think the culture has changed. I grew up in the ‘50s and ‘60s in the United States, and we had something called arts and music education. Musical and artistic literacy was actually considered something good to have; having an education was considered a positive thing. Now we have a situation in the United States were education is being badmouthed, just like the courts, the Justice Department, and they’re cutting all funding for the arts. They’ve been whittling away at this for two generations now. Now you have pretty much illiterate generations who don’t even know who Beethoven is. That is going to have tragic consequences for mankind. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.