- Alexandre Kantorow, Tapiola Sinfonietta, Jean-Jacques Kantorow: “Saint-Saëns: Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2” (BIS)

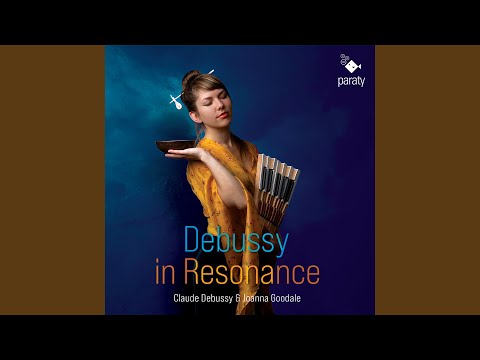

- Joanna Goodale: “Debussy in Resonance” (Paratay)

- Lavinia Meijer: “Are You Still Somewhere?” (Sony)

As the composer himself tells the story, when Camille Saint-Saëns was six years old, he composed a romance for a singer. The 12-bar work left its interpreter’s father so enthralled he gave the young boy a leatherbound score to Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.” It proved prophetic for the young composer:

“Daily in my ‘Don Juan,’ unconsciously though with that wonderful ease of assimilation which is the great characteristic of childhood, I lived in the music, reading the score and acquainting myself with both the vocal and the instrumental parts.… Nothing, unfortunately, is more difficult to interpret than this exquisite music whose every note and pause has a value of its own and where the slightest negligence, whether in letter or in spirit, may be catastrophic.”

No surprise, then, that the first few notes of the opera’s overture turn up in Saint-Saëns’s Piano Concerto No. 2, including the pauses which separate the thoughts between the second and fourth bars of Mozart’s score. It was one of the first things I noticed listening to Alexandre Kantorow’s new recording of the work. It was surprising to do some quick Googling after catching this Hitchcock cameo and find little mention of the reference. Musicians and historians seem to have commented on the elements of seemingly every other composer crammed into the piano concerto, while ignoring this moment just two minutes in. (Pianist Zygmunt Stojowski famously said the work “begins with Bach and ends with Offenbach.”)

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

“Don Giovanni” is like a Rosetta stone for understanding how the seemingly disparate parts of Saint-Saën’s Second Piano Concerto all fit together. Citing the “incongruities” of the opera’s opening scenes, Saint-Saëns praises Mozart’s ability to modify “the character of the music, passing from comic to tragic without breaking the unity of style.” He seems to aim for a similar unity in his own Piano Concerto, beginning with a recognizably Bach-like fugue, before squashing it like a fly under newspaper with the “Don Giovanni” moment. More than 30 years before Rachmaninoff would compose his own Second Piano Concerto, Saint-Saëns’s dabbles in agitated chromaticism, while also fielding moments that share the same creative DNA as Beethoven’s “Pathétique” Sonata. And all of that is just the first movement.

For Kantorow, every reference seems evident, yet he plays them without overstating their significance to the work as a whole. He makes the concerto cohere effortlessly, as if it were one natural thought whose progression he follows from alpha to omega with an Elle Woods-ian sense of “What, like it’s hard?” This collection is the second part of a strong double-hitter of Saint-Saëns’s complete works for piano and orchestra, which Kantorow recorded with the Tapiola Sinfonietta and his father, conductor Jean-Jacques Kantorow. Beyond the opening gambit of the Piano Concerto No. 2, the album is a collection of gems, including the First Piano Concerto and a set of miniatures. It marks the 25-year-old pianist’s seventh album, and continues what has already emerged as a signature for him: taking on works of complexity and ambition by composers in their firebrand eras. It fits Kantorow’s style, at once crystalline and white-knuckled.

Of all things, Kantorow ends his Saint-Saëns cycle with “Africa,” one of several works by the composer that stands as an homage to his second home in Algeria (the winter climate there was more conducive to Saint-Saëns’s always-shaky health). In 2022, that name doesn’t engender much beyond an impulse to share the “Calling Edward Said” meme. Yet when and how Saint-Saëns worked with the musical motifs of the Middle East and Northern Africa is more complex than a simple matter of appropriation. That’s an article for another day, but it is a connection between Saint-Saëns and Debussy, who otherwise saw themselves as diametrically opposed artists working across ideological and generational divides.

Joanna Goodale picks up this thread on “Debussy in Resonance,” a keenly-crafted album that links together many of the composer’s piano solos with Goodale’s own musical responses to those works, particularly in terms of their relationship to both the image of water and Debussy’s geographical and anthropological curiosity. Perhaps it’s my own background as a multicultural mutt, but in the hands of Goodale—a French-Swiss musician born into a British-Turkish family—the album is both a conceptual exercise and a work of standalone beauty. The second track (“Ocean Origin”), for example, is one of Goodale’s originals. Opening with a soft shimmer of gongs, its melody comes through as the happier twin of the subsequent track, Debussy’s “La cathédrale engloutie.” It’s a luminous, rippling étude in the style of the composer. But Goodale’s own Debussy interpretations are the real centerpiece of the project, performed with a grace and subtlety that offer glimpses of the depths of thought and consideration lurking under each note.

In a similar class with Kantorow and Goodale is Dutch harpist Lavinia Meijer, whose Philip Glass album was one of my favorite releases of 2016 both for its performance and curation. Meijer’s follow-up on Sony allows her roving curiosity and capacity for discovering sonic connections to grow. It also furthers her mission of exploring the harp as a contemporary instrument, rather than preserving it as a divining rod for the past.

Some of the strongest compositions on “Are You Still Somewhere?” are Meijer’s own, including the title track, which twirls around a Michel Legrand-ian sense of rue and nostalgia. Even better is the ineffable “Another Lonely Night.” The evening hours plod heavy-footed in the bassline, and there’s the sense of something stagnant in the air; like the midnight hours of a sleepless July evening in a New York City apartment whose air conditioning has failed. A sense, too, of Justina Jaruševičiūtė’s wolf hour. It pairs well with pianist-composer Lambert’s “Stay in the Dark” and Ryuichi Sakamoto’s “Solitude,” three works that get at the heart of being alone and the fine line between companionable seclusion and clammy isolation.

If this is an underlying current of “Are You Still Somewhere?,” it is rendered more literal in the final track, with a spoken-word text by Iggy Pop. The godfather of punk’s unmistakable voice, all gravel and smoke, growls out “Hustle and bustle, baby.” And the two are off. At times, Meijer mimics his cadence in a sort of sprechstimme line. At others, she offsets his woebegone monotone with the sort of pixelated emotional intensity that will sound familiar from her work with Philip Glass. It’s a moving marriage of opposites as Pop moves through a narrative of generational inheritance and loss: “Mom and dad are gone, and I’m not gonna get used to it. I’ll never accept it. I’m gonna find them,” he says at one point, before he underlines the core theme of the entire album: “I have a voice to call out…‘Are you still somewhere?’”

Throughout all of this Meijer makes even the thorniest of passages sound like second nature. Given the inevitability of us all eventually being alone, this virtuosity is a comfort. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.