The sepia photograph, taken over a century ago, shows Ottilie Metzer-Lattermann in a brimmed hat and pale summer dress, standing on a garden path in northern Bavaria. Today, that same garden is blooming with marigolds, geraniums, and bird of paradise flowers. The path moves uphill past shade trees and a waterlily pond, before turning right onto an allée of yews and 53 tall gray glass panels. One of them commemorates Metzger-Lattermann, a contralto who came to the Green Hill for her debut performance in 1901. Over the next 11 years, she returned again and again to sing the roles of Floßhilde, Waltraute, Grimgerde, and, to acclaim in 1904, the major role of Erda.

Flee the ring’s dread curse! Hopeless and darksome disaster Lies hid in its might.

In 1933, Metzger-Latterman was one of 12 German-Jewish singers invited to participate in an opera tour of the United States, a potential refuge. But plans for the tour fell through. She fled to Belgium. There she was rounded up by the Nazis and sent to Auschwitz, where she was murdered.

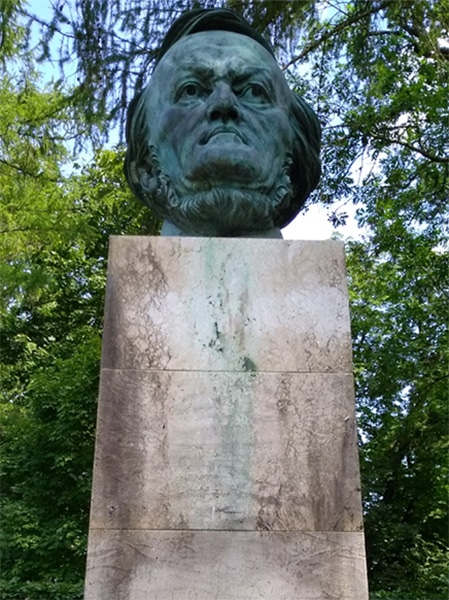

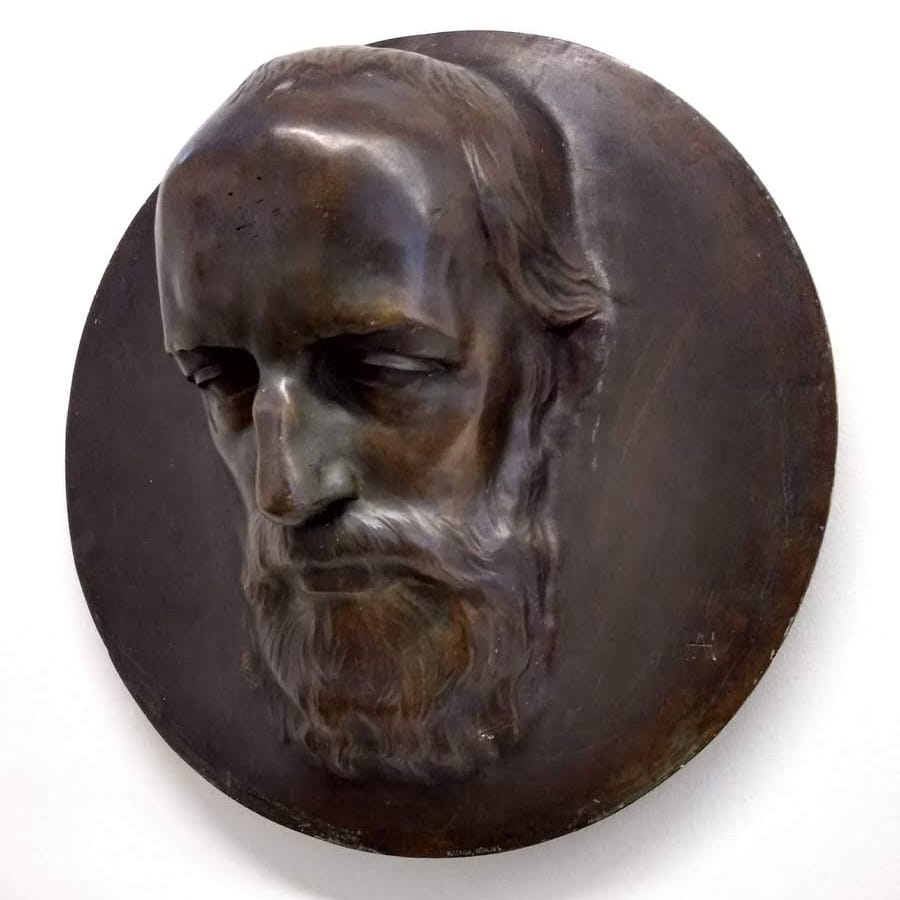

Beyond the memorial panels, at the end of the allée, looms a bronze bust cast in 1986 by Arno Breker. Breker was a member of the Nazi party, a friend of Albert Speer and Hitler, and official sculptor of the Reich. The bust depicts Richard Wagner, the man who gave all of us, including Metzger-Latterman, a reason to come to the city of Bayreuth. The city commissioned the Wagner bust from Breker in 1986. Not 1936. Bayreuth has a way of precipitating the collapse of time, space, ideologies, and fates.

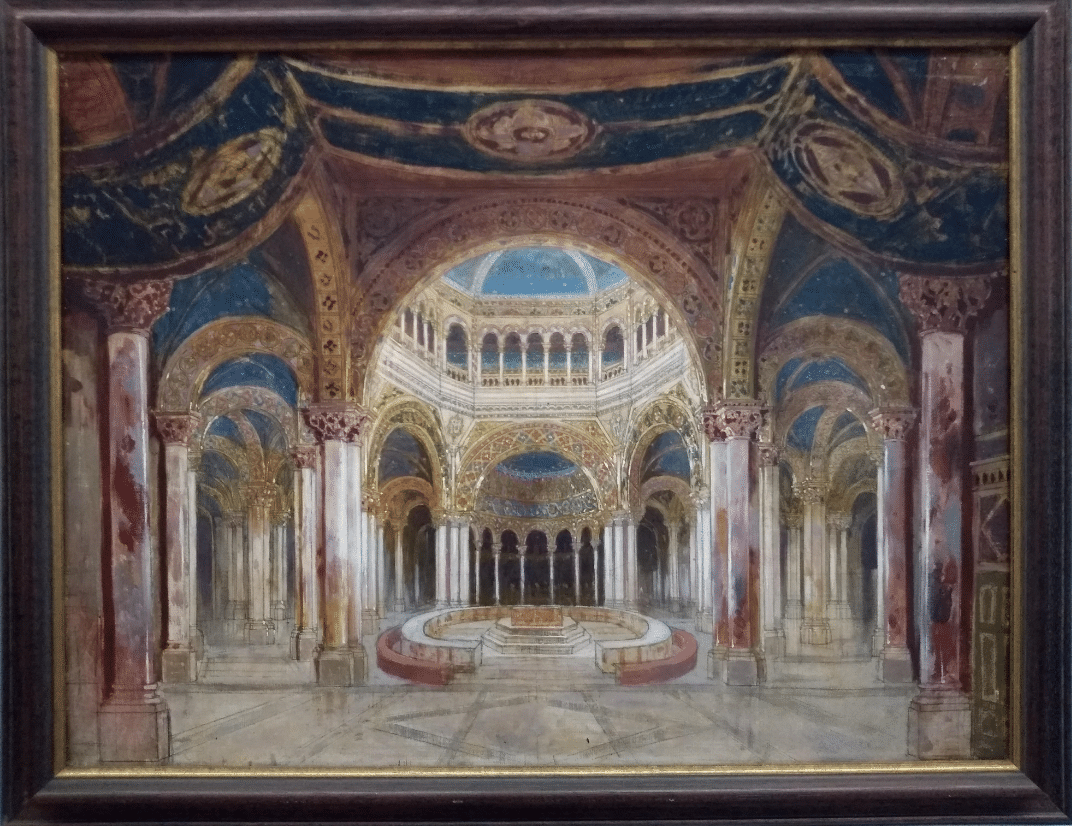

For opera lovers, the name “Bayreuth” connotes the theater, festival, and Wagner’s lifelong dream and masterpiece. He considered himself a creator of “musical dramas,” cross-disciplinary projects of music, poetry, architecture, and design that might finally achieve his ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. Many opera houses mount Wagner productions, but the Festival features his music almost exclusively, in the theater he built for it. Wagner wanted a sunken, covered orchestra pit that would project sound toward the singers, melding it with their voices before bouncing back toward the audience; cushion-free wooden seats for better acoustics; and for his Festival to be accessible to the people, not reserved for the rich and mighty. (After failed fundraising attempts, he had to solicit elite subscribers. But his ideal that every seat in the house, even the budget seats, should be a good seat, prevailed.) The inaugural Festival opened in 1876 with the performance of the first complete “Ring” cycle. In 1882 Wagner premiered “Parsifal,” the Bühnenweihfestspiel, or “stage-consecrating festival play.”

In his foundation-laying speech, Wagner said, “Even now it is firmly and truly laid in order that it may bear the proud edifice as soon as the German nation demands to enter into possession of it with you in its own honor.” And: “May it be consecrated by the spirit that inspired you to heed my call, the spirit that filled you with the courage to trust in me entirely…the German spirit that shouts its youthful morning greeting to you across the centuries.” Then: “On the strength of the foregoing observations, we may end by examining exactly what it is that the German character needs if we wish to take it in the direction of an original development unfettered by foreign motives that are misunderstood or falsely applied.”

The Festspielhaus is not like other opera houses: for the people who’ve come seeking its consecration, and for those who’ve been denied it. The exhibition “Silenced Voices” was installed at Bayreuth in 2012 in tribute to the many singers, musicians, choreographers, and musical directors who, under Wagner’s and succeeding administrations up through the 1930s, were hired to work here, only to face the institution’s bigotry. Most of these artists, for the most part Jewish, a few of them gay, were harassed into resigning, fired, or forced to flee Germany altogether. The section where Metzger-Latterman’s panel stands commemorates the Bayreuth artists who died in the Holocaust.

For the past seven years, “Silenced Voices” has garnered a considerable amount of press, becoming an almost obligatory mention in Festival coverage. I mention it, because I notice a couple, in tux and gown, strolling past the panels in order to pose for a photo with the Breker sculpture. Perhaps they don’t know where and with what they’re posing, or perhaps they do know, but don’t care. Or perhaps they do know, do care, and have decided that the souvenir is worth it, which is what I keep wondering about myself, during my visit to Bayreuth.

II

My first performance of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” changed my mind, literally and fundamentally: it changed the way my brain processed sound. Since childhood I’d had an undiagnosed auditory processing disorder that turned competing sounds into walls of white noise. My hearing tests normal, but I can’t always isolate the tones of a friend’s voice from those of a plastic bag rustling, an air conditioner, or a panting dog. My most frequent answer to the question, “What do you think of the music?” was, “What music?” as I looked around for the stereo or live band I’d never noticed was playing.

But I attended the opera with pleasure and attention. I enjoyed the dramas, the subtitles, and the bright little people waving their hands onstage. I read about opera and played opera music at home. Years of listening-but-not-comprehending slowly rewired my brain, culminating in that afternoon at “Tristan,” when the opening bars finally, inexplicably unscrambled into patterns: these waves and tides were music. I could hear the music. “Tristan” made it possible for me not just to hear music at all, but also to love it.

Recently, during a time when I felt consumed by violence, illness, and the lack of money, I sat up one night past dawn, writing about Wagner’s relationship with Ludwig II of Bavaria, the greatest Wagner fanboy who ever lived. As I worked, I listened to “Parsifal” on repeat. Every time the Transformation played—the music where “time becomes space,” a moment of vulnerability, awe, and humility that tears a rift in all the world’s arrogance and ignorance—I thought, I am so lucky. To be able to listen to and write about opera all night, knowing that even though I’d barely eaten that week, unspeakable beauty still existed in the world, and I wanted to be part of it. I felt so grateful to struggle back to life, toward, and with, that music.

“Parsifal” celebrates the grace that even a fool can bring to a broken community through compassion. The “Ring” releases the hope of renewal into the world, on the ashes of a violent, flawed old order. “Tristan” is—well, “Tristan” is about sex/death—but the finale affirms the expressive power of a woman’s voice. There are far less metaphorically apt artworks in which to find the will to survive.

How much do I love Wagner’s music? I’m celebrating my rebirth by ordering wind chimes customized to play the “Tristan” chord. I’ll hang it in a doorway and riddle everybody with pangs of unresolved longing. If my boyfriend asks, “Would you consider taking that thing down at night?” I’ll say, “Dude, love me, love my wind chimes. Also: can you put on this chainmail?”

In the opening week of the 2019 Bayreuth Festival, I spend my afternoons and evenings attending five performances each of five to six hours’ duration. In the mornings, I go running along the river trail of the Red Main, where spears of magenta wetland orchids, clover, mullein, buttercups, daisies, thistles, hemp-nettles, and giant cat’s-ear are blooming, and the blackberries, cattails, and crab apples are ripening, onward across a sunny meadow, and I know, now, that I’m going to make it.

III

“Bayreuth is not only a sanctuary, a refuge, but also a power station of the spirit of that inner world which we might in a word term idealism,” wrote Baron Hans Paul von Wolzogen, editor and co-founder, with Wagner, of the Bayreuther Blätter (1878-1938), mouthpiece for the sacralization and Nazification of the Festival. Quoted in Barry Millington’s erudite, fast-paced, and drily witty biography Wagner (1987), with this comment: “Nothing illustrates better the perniciously hermitic and narcissistic place Bayreuth had become by 1914 than this sanctimonious gibberish.”

For my trip from New York to Frankfurt to Nuremburg to Bayreuth, I’m reading Brigitte Hamann’s 2002 biography of Winifred Wagner, who married the composer’s son Siegfried and for many years presided over the Festival. Hamann provides a detailed history of Hitler’s connections with Wagnerian opera and Bayreuth during that time; the entries under Hitler’s name in the index alone go on for pages. Hamann discusses Hitler’s youthful enjoyment of “Lohengrin”; his first visit to the Wagner family villa, Wahnfried, in 1923, shortly before his putsch attempt; his romping with the Wagner children; his gift to Winifred of a signed copy of Mein Kampf. For fun, between Nuremberg rallies and massacres, Hitler sketched stage sets for “Tristan” and the “Ring.”

We all know that Hitler was a Wagner fan, but I’m startled to read that in 1934, he practically served as a Bayreuth Festival theatrical producer, not only approving, rescuing, and funding its then-controversial new “Parsifal,” the first production since the composer’s 1882 original, but also recommending and personally soliciting its designer, Alfred Roller. Hitler arrived for the opening of the Festival (for which hastily hired substitutes replaced the Jewish basses Alexander Kipnis and Emanuel List, who’d emigrated) just weeks after the Night of the Long Knives. Barry Millington’s Wagner points out that it was Hitler who realized Wagner’s dream of public arts accessibility at the Festival by ordering the Reich to buy 11,310 tickets for low-income music-lovers. Hamann reprints Winifred Wagner’s announcement: “All working people, whether workers with the head or with the hand, will be able to enjoy the wonder of Bayreuth, in accordance with the desire of the Führer, and in these hours of consecration find spiritual strength and edification, to return home proudly aware that it was German will and genius that created this hallowed place.”

Since 2009, when Katharina Wagner and Eva Wagner-Pasquier became co-directors of their great-grandfather’s festival, the Wagners have opened their family archives to scholarly scrutiny, put up a plaque explaining the Breker sculpture, and hosted “Silenced Voices.” The Richard Wagner Museum, which encompasses the Wahnfried family home, has installed a frank historical exhibition.

The Festival also continues a now generations-old tradition of postwar reckoning with itself onstage. This year it reprised the 2018 “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg” directed by Barrie Kosky, the first Jewish stage director at the Festival. The production turns Bayreuth and the opera inside-out: in a sacrilegious romp through a recreated Wahnfried (as though thumbing its nose not only at Wagner, but also at the museum’s House Rules, which note that “public demonstrations of political, aesthetic, religious or other ideological beliefs or opinions [are] unwelcome”); and by placing the opera’s triumphal final scenes, set in 16th-century Nuremberg (which expelled its Jewish population in 1499), amidst the Nuremberg Trials. Kosky deploys descriptions from Wagner’s 1850/1869 screed “Judaism In Music” to populate the stage with anti-Semitic caricature carnival heads with skullcaps and side curls, and a gigantic caricature balloon head. Kosky’s interventions materialize during moments of musical chaos—then literally deflate, during the peaceful woodwind and sacral resolutions, as though to suggest that, after the purgative explosion of bigotry, Wagner—and anti-Semitic audiences—can move on, having gotten it all out of their system.

Revisiting his production a year later, Kosky writes in the 2019 program that “Die Meistersinger” “is full of breathtakingly gorgeous music. It is full of heart-breaking moments of beauty and melancholy. It is full of genuine and authentic expressions of life and joy and happiness. But it is also troubled and troubling. It just depends who you are in the piece and who you are in the audience.” Tonight, before the final notes have faded, one audience member bellows a deep bass “BOO!” Because he’s offended that Wagner’s anti-Semitism is being put on trial, and it’s interfered with his pleasure? Or, because he doesn’t like the singing, conducting, sets, or the view from his seat? Or…because he is one of the Jewish spectators, who might have felt all the impact of the brutal imagery, and the brunt of Kosky’s calculated risk?

I don’t know. On June 2, 2019, a neo-Nazi assassinated German politician Walther Lübcke for his pro-refugee stance. We are sitting only 80 miles from the Nuremburg rally grounds. Every night, I walk back to my lodgings along Niebelungenstrasse, named after a people in medieval legend who, in the “Ring,” are—surprise!—anti-Semitic caricatures. It’s a lovely walk, superior to the heavily trafficked, banner-lined Festival road. It’s a place to feel a little haunted by the past.

IV

It’s easy for Wagner-haters to deal with his legacy: reject the work, reject the man. And it’s easy for bigots: reject the oversensitive critics’ concerns, for the sake of the art. But after several decades in which the Festival has led the way in its own evisceration, many Wagnerians are Just So Over The Nazi Thing.

Some people fall over themselves to get their references to the anti-Semitism up front and out of the way, so they can establish liberal bona fides, before moving on to the stuff that really matters. It’s a rhetorical reversal of Godwin’s Law: Why, of course Bayreuth was manipulated by the Nazis! But it was Winifred’s doing—she wasn’t a Wagner by blood—and Richard Wagner was dead long before the 1930s, so it wasn’t his fault. Why, of course Wagner wrote propaganda on tropes that were still current at the time of Kristallnacht—but the music is pure, the actual notes can’t be anti-Semitic. Why, uh, well, of course the actual notes in “Parsifal” include Christian devotional motifs to underscore the anti-Semitic themes of Jewish blood impurity and the Wandering Jew…but but but….

I’m disturbed by Slavoj Žižek’s “Why is Wagner Worth Saving,” a 2005 foreword to Theodor Adorno’s In Search of Wagner (1952), in which he declares that critiques of anti-Semitic representations in the operas are wrongheaded and superficial, because they fail to decode the real question of how the “‘Jew’ itself” is simply a cipher for the “‘original’ social antagonism” of “the most elementary disgust, repulsion felt by the ego when confronted with the intruding foreign body.” It’s like he’s never heard that scapegoats get killed.

I’m disturbed by a piece in The Guardian that bemoans the archive disclosures. “The danger of Bayreuth publicising its dirty washing like this is that the link between Wagner and Hitler turns the place into a sort of self-flagellating Nazi theme park, as if Nazism were the only prism through which to interpret Wagner’s music.”

I’m disturbed by the New York Times article that aspires to compare Wagner’s legacy to the 2017 violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, only to backpedal: “The disturbing events of the outside world largely faded for me, though, once I entered the theater.”

If writers for The Guardian think Bayreuth’s acts of accountability trivialize its institutional gravity—if Times reporters sit in the theater where Hitler sat and magically forget, here of all places, that neo-Nazis are murdering people in the United States and Germany—then maybe, for them, the Festival is an amusement park, brainwashing them into insouciance about crimes against humanity.

On opening night, Valery Gergiev (whom some German newspapers call “Der Putin-Freund”) makes his debut at the podium. That same night, I’m astonished to see Angela Merkel sitting only five rows behind me, in the center box. Known and less known government ministers, actors, capitalists, and musicians attend. And Gloria, Princess of Thurn und Taxis. Wait, which Princess Gloria of Thurn und Taxis? The one with the 500-room palace in Regensburg, with whom Steve Bannon consulted to start his Gladiator school for right-wing Catholics to defend the “Judeo-Christian West”? (Italy canceled the property’s lease this summer. Maybe because the school was supposed to foment revolution against Pope Francis.)

Hitler didn’t come to Bayreuth because Wagner’s brand of 19th-century anti-Semitism was unique, or directly modeled his own thinking. He came for the same reason we did: he loved the music. And we’re all still here at the Festspielhaus, seeking beauty, pleasure, criticism, self-indulgence, and absolution. The opera critics. The opera fans. People like Princess Gloria. People like me.

Narrative art often takes the form of a quest, and Wagner’s music dramas take questing seriously, with their wanderers, pilgrims, and seekers. Wagnerians take it seriously, too: sitting through an entire “Ring” cycle is a pilgrimage. Reaching Bayreuth is a pilgrimage. Mark Twain wrote of the Festspiele of 1891:

If you are living in New York or San Francisco or Chicago or anywhere else in America, and you conclude, by the middle of May, that you would like to attend the Bayreuth opera two months and a half later, you must use the cable and get about it immediately or you will get no seats, and you must cable for lodgings, too. Then if you are lucky you will get seats in the last row and lodgings in the fringe of town…There were plenty of people in Nuremberg when we passed through who had come on pilgrimage without first securing seats and lodgings. They had found neither in Bayreuth; they had walked Bayreuth streets a while in sorrow, then had gone to Nuremberg and found neither beds nor standing room, and had walked those quaint streets all night, waiting for the hotels to open and empty their guests into trains, and so make room for these, their defeated brethren and sisters in faith.

It was worse a century and more after Twain’s visit: the waitlist for the opportunity to buy tickets ranged from five to eight years, and, I’ve heard, as long as ten. I once read the dismayed announcement by a Wagner fan society, with a longstanding place in the queue, that the Festival had canceled its group block with no warning or recourse, so everybody had to start over at Year One on the waitlist. Aspirants who’ve succumbed to the temptation of black-market tickets have been bodily ejected and blacklisted. (Just like the eponymous sinner from “Tannhäuser,” who walks to Rome to expiate his sins, only to be singled out among thousands of pilgrims by the Pope: “You are eternally damned! / …. From the burning brands of hell / Deliverance can never blossom for you!”) Very recently, the Festival has started offering a few tickets online. But for as long as I’ve known about Bayreuth, I’ve considered it as unattainable as the domain of the Grail.

When VAN first raised the possibility of press tickets for me, I felt—to quote poor Tannhäuser again—that “From the false sound of promise / Which, icy-cold, pierced my soul / Shuddering horror forced me away with wildly staggering step!” I was just emerging from a rough spot in my life, when the $25 Metropolitan Opera rush tickets I used to evangelize about cost more than I had for two weeks’ food. I was too ill and exhausted to attend free concerts, or even to listen to music at home.

But, because I can’t refuse this opportunity to achieve the impossible, I choose to spend more money than I make all summer on a week’s lodgings. For the astronomical peak-tourist-season airfare, I take inspiration from Wagner himself. In the preface to the “Ring” poem, he’d published an appeal for patronage. “Will this Prince be found?” Miraculously, Ludwig read the 1863 edition and put the royal coffers of Bavaria at his disposal. So I find my own private Ludwig (on Tinder!) (we’re just friends!) (really!), who donates air miles that would have cost me a month’s earnings. (Having a patron of the arts is one thing that Wagner and I have in common; the others are histrionic self-pity and a fondness for luxury home décor fabrics.)

But the pilgrimage has only begun.

On opening day, under a blazing sun, with an outdoor temperature of 96.8 degrees, the ushers shut 1,925 pilgrims into the wooden box Wagner has prepared for us, devoid of air conditioning or fans. We’re not allowed to carry water bottles or secret cushions. Paramedics are ever-present, because people faint on the regular. Over the next five hours—for some reason—I keep thinking about how Tannhäuser and Elisabeth drop dead at the end of his pilgrimage. In “Lohengrin,” Elsa drops dead, too. Also Titurel, Kundry, Tristan, and Isolde. (These productions would all take liberties with plot. But at this point, in the sweatbox, I had no inkling that other fates might be possible, for them or for me.) During “Lohengrin” the following night, I’m suddenly nauseated, have trouble breathing, can’t hear the music over the pulse pounding in my ears, and nearly pass out. But I don’t, because the bare wooden seat back biting into my shoulder blade won’t allow me the relief of unconsciousness. As, I suppose, Wagner had intended.

Parsifal endures years of wandering and assault in the wasteland and war lands, before he’s granted reentry to the blossoming Grail realm. There he shares the Grail’s sustaining radiance with the knights. We at the Festspiele also yearn for radiance. The endless delays, trials, and pains make us feel valiant and long-suffering; the torture is built into the workout, the adventure, the quest, the fun.

“Fun” isn’t the right word for the gorgeous singing I hear this week, the luminosity and richness of the voices of Camilla Nylund (Elsa, Eva), Markus Eiche (Wolfram), and Stephen Gould (Tannhäuser, Tristan). It’s my sixth time hearing Michael Volle (Hans Sachs): I’d listen to him sing “Trololo” for the length of a Ring, that’s how magnificently charismatic, dramatic, and nuanced his voice is. I’m liking Klaus Florian Vogt (Lohengrin, Walther) more and more, as (like Lohengrin!) his famously otherworldly sound has started sinking roots into the ground. “Fun” doesn’t describe my doubts and discovery with Petra Lang’s occluded, and dare I say, hooting, Isolde, which forced me to listen harder, until I found the confident exactitude of her movement through the lines, the gleaming, utterly singular beauty of her colors. Loving music the way you’ve always loved it is easy; learning how to love what you don’t think you even like is transformation.

What is uproarious, laugh-out-loud fun is the first sight of Tannhäuser (Gould) and Venus (a warm, determined Elena Zhidkova) roving the countryside in her Citroën van circus clown-car—in tribute to Marina Abramović—in the new production of “Tannhäuser” (director Tobias Kratzer, stage and costumes by Rainer Sellmaier, video artist Manuel Braun, dramaturge Konrad Kuhn). In the original, typical conception of the work, the title character wavers between lawless pagan sensuality, represented by the Venusberg, and the blessings of Christianity, law, tradition, and love, through the Wartburg. Here, Venusberg is more than a sex lair (nothing against sex lairs, but): it’s a close-knit, creative, anarchic, improvisational, punk art-as-life community, while the Wartburg is a hilariously, lovingly, and aptly satirized Bayreuther Festspielhaus.

I’d never seen an opera audience so united in the hijinks—or, for that matter, in appreciation of “Tannhäuser,” about which so many of us said, “I never even liked it before!”—as, through Braun’s video projections, we joined the clowns in nicking fast food, siphoning gas, and leaving a wake of glitter, music, kisses, and laughter behind, all to the music of the Overture. Then the fun literally comes to a halt. A traffic stop. A cop.

Venus, at the wheel, runs him over with her van.

Nobody in the audience knows how to respond. What I can see is that Venus’s community of free-spirited artists lives precariously. Broke. Without IDs. Black, queer, disabled. People perilously at risk of being murdered by police. Venus knows that killing is wrong. She also knows that handing over vulnerable people to the institutions that dehumanize and destroy them is another form of murder. So she chooses. Her decision breaks Tannhäuser, who flees to the Wartburg, which supposedly offers the safety of ethical and aesthetic order, of correct choices without compromise or guilt.

This all happens in the Overture and first scene! While many productions would set up this tension, then peter out from lack of direction, this one’s only started. Its development of every note and word through singing, acting, design, and finely balanced video and live action creates what Braun calls in the program interview “an inquiry into the way we relate to the world in this day and age. What kind of life do I want to lead? What is right and what is wrong? Comfort is always the easy way out, but sometimes, things have to be uncomfortable.”

This “Tannhäuser” was the most wild, antic, tender, and thoughtful operatic experience I’ve had in years. And it’s uncomfortable, because it exposes the myth of good conscience. But the call is coming from inside the Festspielhaus, which, on opening night, is full of plainclothes cops. (Well, fancy-clothed, in gowns.) Tobias Kratzer says, “Everything becomes institutionalised at some point…until, in the end, even institutional critique is assimilated into the institution.” In Act II, Venus’s crew has infiltrated the Festspielhaus and draped a banner over the iconic balcony: “Free in wanting, free in doing, free in enjoying” (“Frei im Wollen, frei im Thun, frei im Geniessen”), from Wagner’s The Revolution, 1849. Cut to another backstage video that provokes gasps and mirth from the audience: the person who calls the riot cops on the happy, costumed protestors is Katharina Wagner. Of course.

Earlier that day, I’d somehow gotten lost between the bus stop and entrance to the Festival. Wandering the back service passages, I opened a delivery gate directly onto the plaza where Festival guests drank champagne, thus bypassing the police checkpoint where Merkel’s attendance mandated stringent ticket, passport, and bag checks. But nobody raised an eyebrow as I sneaked in, because in a place like Bayreuth, no matter how contrarian I feel, I’m not Venus’s crew, but the Wartburg’s.

This “Tannhäuser” suggests that the yearning for radiance and innocent pleasure, free of guilt—and for the satisfaction of always doing the right thing—is the start of ethical and aesthetic ossification. Not because art, music, and ideology must be contiguous. Not because the criticisms and self-reflections aren’t good, because they are; not because I think everybody here is a neo-Nazi, though some of us are. (The Festspiel is hardly unique among arts institutions in that regard.) I want radiance as much as the next person, and the Festival is splendidly capable of providing it. What troubles me is my persistent yearning for a radiance that can be pure and simple at all. Art emerges only from and with our world, including the ugliest aspects of history, contemporary conflict, and the suppression of human dignity. What’s ridiculous—inhumane—is to come to Bayreuth and to expect not to feel this. To exempt the Festival from being taken seriously in a living, breathing, suffering, beauty-making world. To expect an innocent, purged, cleansed Bayreuth that has nothing to do with the world at all, that doesn’t matter, like an indigestible lump that passes through the body and comes out unchanged and unchanging.

VI

When Parsifal first breaches the domain of the Grail, carrying a locally beloved swan he’s shot dead, and witnesses the Grail’s unveiling, the knight Gurnemanz asks, “Do you know what you have seen?” Parsifal shakes his head. He’s a fool. But not just any fool: he’s the prophesized pure fool, who’ll be made wise through compassion!

“Parsifal” is the most gesamt of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerke, because he roped God into it as both subject and rubber-stamp approver of his building and compositional plans. “Parsifal” is also steeped in anti-Semitic notions of blood impurities that must be washed away by salvation and, optionally, death. Its first conductor was Hermann Levi, the son of a rabbi; Levi’s appointment was made, and then enforced, by Ludwig, who was not an anti-Semite. Wagner and Cosima bullied Levi with anti-Semitic gibes, declared him unfit to conduct the sacral play until he’d been baptized—then said, Just Kidding!—and finally hounded him from Bayreuth with trumped-up charges of lechery.

As Millington describes, after Wagner’s death, his widow and associates accorded “Parsifal” special standing in Festival culture, lobbying for copyright extensions to deny performance rights to any other theaters. “Grail Brotherhood,” “Bayreuth freemasonry,” “unsere Sache (our affair/mission),” and “soldier of Bayreuth Idealism” were the terms with which they developed a sort of Parsifalian secret society, or cult. This persists today in the tradition of not clapping after the first act of “Parsifal.” Beforehand, I wonder: Is it polite to comply with tradition? Is it just fun? Or is it creepily cultish and proto-fascist? The Festspiele website refrains from legislating this.

Then Act II begins. In this 2016 production of “Parsifal,” set in a contemporary Christian monastery in Iraqi Kurdistan, the evil character Klingsor (in the original, an ambiguously anti-Semitic and Islamophobic caricature) prostrates himself to pray, then indulges in a cross and self-flagellation fetish. The Flower Maidens seduce Parsifal while wearing hijab, then strip down to belly dancing costumes, an irredeemably Orientalist harem fantasy. In the sacral conclusion, which the production thinks is disavowing divisive faiths, Parsifal still conducts baptisms—then strips off a woman’s headscarf, and another. This reminder of European bans on Muslim women’s coverings is, to my eyes, a misogynist, racist, Islamophobic gesture of invasion, in the name of secular humanism. And let’s not forget that the original text invokes the Crusades.

Beliefs about the sacred hold powerful sway. So do beliefs about the impious, the dangerous, the evil. But my disgust with this production is so very much easier for me to manage than what I felt during the Transformation, conducted with grace and grandeur by Semyon Bychkov and integrated to heartrending effect with Gérard Naziri’s video. To the swell of strings, we plunge into the basin of the Grail—and then zoom out to a vanishing aerial view of the monastery, in that town at war, retreating farther and farther till we’ve left the atmosphere, the solar system, all of us together in that little wood vessel of a theater shooting into the cosmos. And then—falling back toward earth, toward this time, this place, the basses, violins and bells assimilate us back inside the great, beating heart of Bayreuth. The Transformation summons the horror and beauty of immanence in a world we can never fully know, justify, or call our own, but in which we cannot help but be terribly present.

It would be so easy, so relaxing, to be a pure fool. To shrug, shoot swans, look upon Grails, be seduced, and still bring salvation to the world, while disowning any wisdom or responsibility. To fill ourselves with the pure, innocent love of music, as one of our most personal expressions of selfhood and desire.

It’s easy to put Wagner and the Festival on trial. It’s harder for those of us who still love the music to ask whether, in this time and place, we can still believe in any kind of “purity” of pleasure, enjoyment, belief, and, perhaps especially, absolution. Bayreuth is a place that has forever championed and forever broken the cult of purity: purity of ethnicity, creed, and nation. But also more intimate cults of integrity, including the belief in the purity of our aesthetic judgment. Of authentic, inchoate, depoliticized response to beauty. And, above all, of the purity of our own stringent, well-considered consciences.

What if you suspect that the thing that brings you your most exquisite sensations of joy is inextricably entangled with violence? We may choose, as music director Christian Thielemann has, to decide that it is resolved. “I defended myself against political correctness because it would have meant tearing something out of my heart that I wasn’t ready to give up for anything. And so I was thrown back on my idols,” he wrote in a 2016 book on Wagner. Or we try to refute our uneasiness by deploying “good” history, the Wagner fandom of Langston Hughes, Edward Said, and every Jewish singer, musician, and conductor who’s tried to reclaim the beauty. (Leonard Bernstein said, “I hate Wagner, but I hate him on my knees.”)

I’ve come to make a personal reckoning with unwieldy beauty and irreparable brokenness. Because I love Wagner’s music. Radiance, art, and love tend to evade our efforts to contain or adjudicate them. But so does ethical inquiry: it always must exceed our limitations—and even our ideals. I suspect that what I love even more than the music is the tempting, pernicious belief in my own clean conscience, in the purity attainable by self-conscious acts of criticism, ethical disassociation, and condemnation. But complicity requires neither our volition nor our acknowledgment. Perhaps discomfort is the privilege, and obligation, of being a Wagner fan.

These things cannot be reconciled or settled; they shouldn’t afford us the luxury of moral smugness. I can’t forget, wash away, or fully disavow myself of what I participate in; I can’t contain its impact or consequences on the world; I cannot be redeemed by this uneasy truce with Wagner. Critique has no purity, either. None of us are safe from the ethical laziness of our own complacency.

Once upon a time, there was a 19th-century German composer who could bring unresolved feelings and mixed motives to artistic apotheosis, who could, as Adorno wrote, with a single chord tell “both of the poignant pain of non-fulfilment and of the pleasure that lies in the tension.” This is the very definition of Wagner fandom. Can we take it as seriously as Wagner did? Can we live with discomfort, not feeling very good about ourselves when we imagine friends saying, “Oh for fuck’s sake, she’s writing about Wagner again: does he really need the bandwidth? Who’s benefiting from this outpouring of attention? Who’s getting publicity and funds, and who’s in the crosshairs of his impact?”

One thing Wagner shows us is that, while it’s awesome to reach a point of sublime, soaring resolution, that’s when somebody dies. This murky reckoning with ethical compromise is not supposed to make us feel that we’re on the right side of history, or that, like Tannhäuser, we can afford the delusion of redemptive choice. But we don’t stop trying. There is no such thing as absolution, for anybody alive to the complexity, dynamism, and radical vulnerability of survival in this world.

VII

Once upon a time, a Wagner fan with unresolved feelings was hired to direct “Parsifal” for the Festspiele. His infamous production garbled and muffled the music, filled the stage with trash, moss, and decay, and substituted a rotting hare pullulating with maggots for the sacral dove. The following year, he went out and built a self-flagellating Nazi theme park: a sparkling, Wagner-and-Hitler BDSM carousel called “Odins Parsipark.”

I became familiar with the work of Christoph Schlingensief at the 2014 MoMA PS1 retrospective, where I watched grainy footage of his 2004 “Parsifal,” rode the “Parsipark,” and returned for more the next day. Schlingensief was my first tour guide through my journey with Wagner. His immense body of theatrical, film, and installation work reflected his concerns with social justice, colonization, poverty, immigration, illness, and German history, even when it was objectionable (exploitative and racially insensitive). And he was haunted by Wagner, so much so that he finally had to build his own Festspielhaus: Operndorf Afrika (Opera Village Africa), a music school, medical clinic, and culture center he initiated in a Burkina Faso village in 2010, and then ceded to community control.

A piece of unscripted film in “The African Twintowers” (2009) records Schlingensief melting down with rage, desperation, grief, and self-pity. The following year he will die of lung cancer. So many of his plans will not be realized. We see him walking away from the camera, weeping, and listening to “Tristan” on his earphones. Wagner, for him, was a torment that could never be resolved—and a consolation, in the same necessary and unsatisfying way.

Maybe, those of us who continue to love Wagner will have to remain haunted by these questions and our inadequate answers. To be troubled, even anguished. To follow our pleasure, but never to feel satisfied that we’ve justified keeping Wagner in this world, just because we want him. At the end of “Götterdämmerung,” when the world as we know it does end, what’s left isn’t the gods, but humans, who will have to reckon with a world profoundly beautiful. And disappointing. And still haunted. ¶

Comments are closed.