Theme

Vladimir Jurowski will become music director of the Bavarian State Opera in 2021. He has been leading the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Enescu Festival in Romania since 2017. He will remain principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and artistic director of the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation, based in Moscow. He has been music director in Glyndebourne, Bologna, and at the Komische Oper in Berlin, where he has lived since 1990. He was born in Moscow in 1972.

I. Stardom

What makes a conductor a star? It could be a herd of cows (John Eliot Gardiner). It could be abuse allegations and impending lawsuits (James Levine, Charles Dutoit). Or it might be the privilege of hip surgery on the North Italian coast (Riccardo Muti). It could be boos at Bayreuth (Plácido Domingo), though he’s more of a star singer/conductor. (Emphasis on the slash.)

The only thing Vladimir Jurowski has in common with these men is a fundamentally transitory existence, like a migratory bird. Moscow, Berlin, London, Bucharest, Munich, Zurich, Paris, Venice, Bologna, Wexford, Glyndebourne, New York, Philadelphia—all are a tiny bit like home.

Migratory birds like starlings have a way of annoying farmers, feeding on fruit and sprouting crops, leaving chaos in their wake. Many a star conductor has been known to leave chaos in his wake, too. Not Jurowski.

If we return to the original metaphor, though, Jurowski’s star is shining especially bright at this moment. In three years, he will take a job once occupied by Kirill Petrenko and Hans von Bülow, Bruno Walter and Zubin Mehta, Georg Solti, Hans Knappertsbusch, Richard Strauss.

II. Student

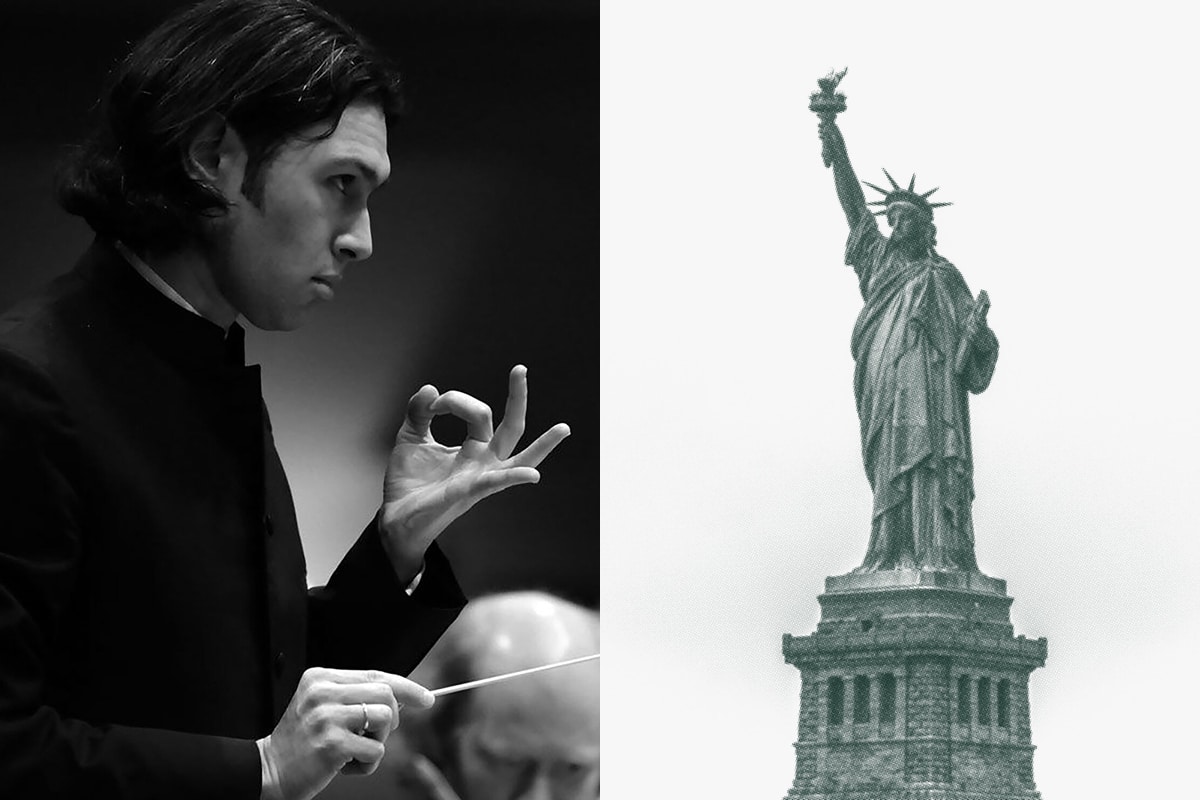

Jurowski has black hair down to his shoulders. He looks less like a maestro and more like a student; a perpetual graduate student, rather, since his black hair is speckled with gray. You might think of him as the Platonic ideal of a student, never hanging out, always diving deeper. He calls his work an incredibly protracted process. The real progress is made at home, not in rehearsal.

III. Berlin

Where does Jurowski call home? His English Wikipedia page calls him a Russian and British conductor, the German version, with a distinct reserve, ein russischer Dirigent. He lives in Berlin. He likes to visit the Botanical Garden, child in tow. It’s easier to become a Berliner than a German.

IV. Eternity

Man and his environment is the theme for Jurowski’s second season at the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. We don’t really think of “Das Lied von der Erde” as being about nature, he says. It’s summer, and we’re way over the agreed-on 30 minutes for the interview. It has descriptions of nature, but it’s mostly about humanity. Still, at the end of the piece, he has the mezzo-soprano repeat the word “eternal” nine times, to describe the beauty of the earth, which he is certain will outlast him. We can’t be so sure about that anymore.

V. Morals

Jurowski introduced the theme for the season in February over breakfast with a small group of journalists. The Radio Symphony is collaborating with environmental groups like Greenpeace and Naturschutzbund Deutschland. (NABU’s “featured” bird of 2018 is the starling.) The program book this year comes wrapped with peppermint seeds.

All of this could come across as self-righteous, but it doesn’t. The facts of climate change clearly bother—even torment—Jurowski. Pouring tea from the samovar, we chat briefly about bicycles. Jurowski is embarrassed that he drove to the meeting today. He would have had to ride eight miles; it’s eight degrees Fahrenheit outside. Cyclists in Berlin keep getting hit by cars and dying.

VI. Winter

Juroswki likes the cold, he says. But he misses the snow.

VII. Fallow Summer

Nothing grows from the peppermint seeds, probably because I’ve never had much of a green thumb.

VIII. Summer Biking

I have a bicycle, Jurowski tells me. But to be honest, I only use it for pleasure, for trips or short distances, like when I need to pick up a loaf of broad. Biking to work is just too dangerous. I’m a good cyclist, but I know what traffic here gets like. It’s scary. I do love biking in my neighborhood, near the Botanical Garden.

Meanwhile, Berlin is experimenting with policies to encourage people to use sustainable forms of transportation. Will we ever see a world famous conductor biking to the Philharmonie?

IX. Mahler’s Bicycle

When he was living in Hamburg, Mahler wrote a letter to a friend about his love of the bicycle. It’s full of untranslatable puns.

X. Diversion

In his first season at the Radio Orchestra, Jurowski played four Beethoven symphonies in pompous arrangements by Mahler. The consternation was palpable. That’s what Beethoven used to sound like?

In his New Years concert, Jurowski went a step further: he slid Arnold Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw” between the third movement and the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. I think it only works with Schoenberg, and then only in the Mahler arrangement, he says. We know that the Mahler arrangement was the version that Schoenberg conducted from. Mahler’s version is in his archives, with his markings. That was “normal” Beethoven for Schoenberg.

Some subscribers, used to the New Years concerts under Jurowski’s predecessor Marek Janowski, thought this was going too far. The insertion of the Schoenberg—originally an idea of Michael Gielens, from the ‘70s—was more unsettling than Mahler’s changes to Beethoven.

XI. Beethoven

Mahler, like Brahms and Bruckner, uses Beethoven’s vocabulary. They change its meaning, of course. But Beethoven is concerned with the most fundament things. He is the basic matrix of our musical existence. Without Beethoven orchestral music wouldn’t exist—imagine that. Sure, Haydn and Mozart got things started, but Beethoven was the one who changed everything.

XII. Critics

Jurowski’s Mahler’s Beethoven had critics flustered. One said that the performance of Beethoven’s Fifth sounded bloated and vainglorious. Apparently, he didn’t look at the program; he didn’t notice that this was Mahler’s version.

I read some of the reviews. But at some point, I realized it wasn’t worth it, except for a few people who actually have some knowledge and ideas. Critics simply aren’t well informed enough.

Before the next concert—of the “Eroica,” with an extra helping of heroism courtesy of Mahler—Jurowski spoke with the audience, as he tends to do. He spoke for 12 minutes, about the same length as the symphony’s finale. His point: You don’t have to like it, but you have to know it.

XIII. Descendent

Jurowski and the Radio Symphony Orchestra go way back. I got to know the orchestra as the East German period was ending, exactly 28 years ago, he tells me. My family came over from what was then the Soviet Union. I started studying in Dresden right away. My father was in Berlin, and I’d visit his rehearsals and recording sessions with the orchestra.

I substituted as a conductor for the orchestra in 1997. It was a tricky program: works by Karl Amadeus Hartmann, Udo Zimmermann and Lutoslawski’s “Mi-‘arti,” an aleatoric piece. I’ve seen the orchestra at so many different stages of its existence and have always admired its professionalism. I never saw the musicians complaining in rehearsal. Sometimes there’s tension between conductor and orchestra, but I never had the feeling that the work was being sabotaged. That never happened here.

XIV. Sabotage

It’s happened elsewhere. Luckily I haven’t experienced it myself all too often. A few times, but those were unhappy exceptions. I never went back to those orchestras.

XV. Ascendant

Maybe Jurowski wanted to take over the Radio Symphony because it runs in the family. The orchestra was consolidated under Marek Janowski between 2002 and 2015; Berlin had had two separate radio orchestras, and when the city was in financial crisis, at the turn of the millennium, that was one of the first things to go. The new Radio Symphony plays at least as well as the more illustrious competition, the Philharmonic and Barenboim’s Staatskapelle. Will Jurowski help them become as famous? It doesn’t seem like his priority.

XVI. Freedom

That’s something he has in common with Janowski, his predecessor at the Radio Symphony. Besides that, the two couldn’t seem more different. 33 years and a gulf in personality separate the two conductors.

After Janowski’s tenure, they were in top form technically. They might have forfeited some of their confidence as a group, though. Things were different in London. The orchestras there are used to playing without a conductor and still making sure that everything works. They would cease to exist otherwise.

Although he and I are very different, I didn’t need to try and “improve” the mood in the orchestra. The need to make music, the love of music—that was already there. Now the standard is even higher. I hope that my different way of making music and my repertoire choices have started to make a difference. The orchestra plays with more independence and freedom in all kinds of music, from early classical to late romantic to 20th century and contemporary repertoire. In this season it’s ranged from Bach to Gérard Grisey and Brett Dean.

I think that strengthens the orchestra’s willingness to work and widens its musical horizons. The musicians need to study and prepare thoroughly on their own. You can’t do everything in rehearsal—a lot needs to come from the musicians. I hope that guest conductors feel that too: that the group is more than a well-oiled machine. It should be a collective, with its own will and musical ideas.

XVII. Blooming Summer

It’s been a month and a half since we last rehearsed, Jurowski tells me in August. They need to get warmed up again, but it’s astounding to me how quickly an orchestra like this comes back together. Other orchestras work summers—my London orchestra never stops playing. This group, back from vacation…I’ve heard worse.

XVIII. Mahler and the Deep End

A day later, the orchestra is heading out to the countryside surrounding Berlin. There’s no time to rehearse, but that’s part of the adventure.

This is our first time doing Mahler’s First together. The orchestra played it last season under two different conductors—probably two different versions, who knows? We have one rehearsal, and the concert’s tomorrow. It’s an interesting experiment, but I think it’s fitting, because we’ve known each other well for over a year now. Over the last couple of years we’ve been rehearsing almost to excess. It’s time to jump in at the deep end together.

XIX. Cuts

To rehearse Mahler One, Jurowski brings his own parts. He’s also carrying his copy of Franz Schreker’s “Die Gezeichneten,” which he will conduct a month later in Zurich. A critic will write of Jurowski’s cuts, “The tectonic structure of the music is destroyed…the score is taken apart and glued back together in the wrong places.”

Doesn’t Jurowski know what he’s doing? Was the critic listening with his ears closed? Jurowski is a conscientious musician. It’s impossible to imagine him not taking something seriously. That doesn’t mean he’s never wrong.

XX. Detours

Jurowski has a taste for detours, unlike some critics and members of the audience. Understanding Mahler by way of Beethoven. It’s a way of training the orchestra. It’s also pragmatic: the entire ensemble gets to play. But it’s not just about practicing, it’s about understanding. Jurowski conducted a youth orchestra in a Schumann program recently, and he chose to play Hans Zender’s “Schumann-Fantasie.” Can a gigantic orchestral piece, including seven percussionists, illuminate something new in Schumann’s piano miniatures?

XXI. Pain and Pleasure

A part of Jurowski’s audience is putting in the effort. I see more and more young people in our concerts, he says. They’re obviously not subscribers. They buy their tickets at the last minute. I’m counting on them, they’re the future. Of course our subscribers are very important to us. But they have a different, more bourgeois way of approaching art: they listen for “pleasure.” For young people art can be shocking and painful. It’s supposed to shake you awake. That can’t work for everybody. I understand why we’ve lost part of our audience, and that we’ll continue to lose people. But I believe that you have to accept this risk if you’re going to have an impact.

XXII. New Mozart

Jurowski’s heroes are conductors who polarize productively. Michael Gielen, Hans Zender, Pierre Boulez. It’s not just about new music. Mozart can be brutal. Happy new ears is the title of Zender’s book.

XXIII. Old Mozart

If you play music the old way sometimes it sounds new. Before he took over in Berlin, Jurowski conducted Mozart’s Requiem. It was a tentative step in the right direction, he tells me. The orchestra followed him. For the “Prague” Symphony, which he conducted in June 2018, the hornists volunteered to play their parts on natural horns.

XXIV. The Eternal Future

By now, it’s conventional wisdom that an orchestra must know how to convincingly perform and understand new music as well as early music. Easier said than done. For Jurowski, it’s an existential question.

We’re not the only ones. We’re a bourgeois institution with a long history and tradition, and we need to make sure we get with the times. The world is developing extremely quickly. With ensembles out there like—I’m just tossing out a few names—Teodor Currentzis and MusicAeterna, Gardiner’s Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, Nick Collon’s Aurora Orchestra, François-Xavier Roth’s Les Siècles…you have to make sure that you’re offering something too. Not just good quality, but also invention, new ideas, in programming and presentation.

XXV. Hunger for Art

Do we take art for granted? When we were students, we had so few opportunities that whenever something was going on, we went, Jurowski says. These days we have so much more access to art—to all forms of information—but for some reason we don’t feel like engaging with it.

For Jurowski, it’s still different in Moscow, his hometown. The attitude toward art and culture there is old-fashioned. But people are closer to the art, they’re more willing for it to affect their personal, emotional, intellectual lives. And they’re less spoiled. I love how the audiences there, because they’ve known me for so long, trust me and my orchestra [the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation]. We can do a program where all the pieces are from the 20th and 21st centuries, and it’ll be packed. That doesn’t happen in Berlin, even for conductors who are a lot more famous than me. If it’s not Beethoven or Wagner…people only care about the composer and the work. In Moscow, they think about who is doing it. There’s an almost childlike belief in the strength of the artistic personality. And once they’ve decided to trust you, they follow you everywhere. In general, there’s a huge appetite for new art.

XVI. Hunger for Food

Moscow seems strange to Jurowski sometimes. It’s a recent shift. Things he cares about, like climate change and the environment, hardly seem relevant there. The people are busy with their own lives, Jurowski says, but the problem comes from the top; like in the U.S., where the president pretends climate change is a figment of a small minority’s imagination. I get the impression that the Russian elite couldn’t care less about the environment, Jurowski says.

The situation for democracy and freedom of speech isn’t much better. There’s the detainment of the director Kirill Serebrennikov, and the case of the Ukrainian filmmaker Oleh Sentsov, who was sentenced to 20 years detention by a kangaroo court. It’s obvious how angry this makes Jurowski. When we spoke, Sentsov was on hunger strike. In early October, after four and a half months without a concession, and the threat of forced feeding, Sentsov gave up. His kidneys, stomach, and intestines are damaged, he has rheumatism and problems with his heart and liver, his lawyer says.

I miss an openness and a feeling of freedom in Moscow. It’s simply not a free country anymore. You can end up behind bars for telling the wrong joke. That was different 15, 16 years ago, when I started traveling to Russia again. It wasn’t as developed as Western countries, but you still had the feeling you were in a free place. I don’t have that feeling anymore. I still go, because it’s my country, because I have my orchestra and my friends there. I also think it’s important, as Iván Fischer says: if a person is sick, you bring him fruit and medicine and tea. You don’t abandon him. His country is sick, he says. That’s exactly how I feel.

It’s scary to think about where the country is going. Because there’s misinformation everywhere, it’s like a new curtain is being drawn around the country, maybe not iron, but leather. People only care about their own lives, their own problems. Everything else is none of their business.

XXVII. Opposites Attract

In Munich, Jurowski will become a neighbor of Valery Gergiev. It’s hard to imagine them hanging out. It’s as difficult to imagine Jurowski getting close to Putin as it is to picture him doing Gergiev’s dramatic gestures. Compare the two conductor’s fingers; that’s enough.

Jurowski does know his predecessor at the State Opera, Kirill Petrenko, well. Jurowski likes to talk; Petrenko is more of the silent type. In thoroughness, in seriousness of intent, they’re very similar, like fraternal twins.

XXVIII. Books and Morals

Maybe they are both moralists. Fabian: The Story of a Moralist is the title of a 1931 novel by Erich Kästner, which has recently appeared in a longer, more radical original version. Jurowski had just finished it when we spoke this summer. Exciting, inspiring and horrifying, he calls the book.

I used to swallow tons of books, but I can’t read as many things at once these days, he tells me. I’m studying so many scores, which obviously reduces my intake of new books.

He’s reading Hidalla by Wedekind right now, the story on which Schreker’s “Die Gezeichneten” is based. He’s also preparing for a “Walküre” with the London Philharmonic by reading North German legends and academic texts, including an obscure musical-psychoanalytical study of the Ring.

I come from the theater. I’m interested in the Gesamtkunstwerk. In the beginning there was the text, he says.

XXIX. Doctor Faustus

After a performance of works by Claude Vivier, with his contemporary music group ensemble united berlin, in a panel discussion, Jurowski says that Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus was one of the books that influenced him the most. Is Jurowski the only conductor under 50 who’s actually read Doctor Faustus?

XXX. Monk and Mystic

In that same panel discussion, Jurowski adds that, like Vivier, he once wanted to become a monk. In Vivier’s “Hiérophanie,” the conductor wears a cassock. It doesn’t look like a costume on Jurowski. It feels right.

Jurowski’s idea never became concrete. It was more of a feeling, a daydream. It came from the way religion was taboo in Jurowski’s youth, and from a sense that a monk is a kind of ideal student. He devotes himself to one thing only. When he’s studying a new score, Jurowski says, he forgets everything, he doesn’t eat.

In the meantime, he distrusts organized religion. He prefers the solitary searchers, whatever their creed. I’m not a monk, I’m a mystic, he tells me.

XXXI. Monk and Conductor

What else do monks and conductors have in common, besides the revelations of the #MeToo era?

To take the question seriously: a conductor, not in the “maestro” sense but in the true sense, must be a craftsman, but also a kind of intellectual leader and teacher. Not in a sectarian or ideological sense, but as an example of how self-sacrificing work can spur people to heroic deeds. He laughs a little at his own grandiosity.

XXXII. Conductors and Demigods

Jurowski is serious, but he is allergic to pretension, the kind that leads fans of Kirill Petrenko to praise him as a messiah.

There’s something ridiculous about it. It’s the same with my colleague Teodor Currentzis. I have great respect for him, but a lot of people treat him like a demigod. I don’t get it. I understand when people worship older conductors or those who’ve passed away, like Carlos Kleiber or Leonard Bernstein. They were people too, but I still get it.

But we’re still alive. We’re even relatively young. That kind of praise isn’t good for the soul. It’s bad karma. And we don’t create music. Those who do might be deserving of this treatment. And I’m proud that I knew some of them, Schnittke, Denisov, Henze. If anyone’s a demigod, it’s them. Not us.

XXXIII. Spirit

Jurowski is planning to complete his Bruckner and Mahler cycles. There are a few standards he’s never done, like Beethoven’s Eighth, Mozart’s Symphony in G Minor, “Nozze di Figaro,” “Così fan tutte.” He’s interested in the baroque: he wants to do more Bach and is fascinated by Handel.

What does Jurowski never plan on conducting?

Plenty. “Carmen.”

He answers quickly. Then he reflects: he can’t find a way to love some of Verdi’s works, like “Un ballo in maschera” or “La forza del destino.” He prefers “Der fliegende Holländer” to “Lohengrin.” Plenty of Strauss is strange for him, too. I’ve never felt the need to conduct “Ein Heldenleben.” It’s so bloated, self-important and loud. There’s humor, but it’s always at the expense of others.

And yet, I love the “Alpensinfonie.” I find it deeply inspiring, maybe because of the spiritual component.

Theme

Vladimir Jurowski will become music director of the Bavarian State Opera in 2021. He has been leading the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Enescu Festival in Romania since 2017. He will remain principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and artistic director of the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of the Russian Federation, based in Moscow. He has been music director in Glyndebourne, Bologna, and at the Komische Oper in Berlin, where he has lived since 1990. He was born in Moscow in 1972. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.