Nearly a century ago, when my ancestors landed in the United States as a family of Syrian refugees, my great-grandmother Nabiha’s name was changed to a more Americanized “Mona.” The story was always relayed in my family with matter-of-fact pragmatism, though no one caught the irony that the new name has its own roots in Arabic, Muna, which translates into “unfulfilled wishes.”

I think of this brand of Ellis Island castration often, especially in the context of opera, an art form I was introduced to by my Syrian grandmother. With extensive roots in the Middle East, opera’s own history is similarly cut off, obscuring the true extent of its legacy.

For centuries, opera’s origin story has been dated to Medici-ruled Renaissance Florence where the Camerata spent much of the late 16th century philosophizing on art and ideas, hitting on the notion of Ancient Greece as a model for a more perfect union. The first operas came out of their focus on Greek tragedy and the theory that it had been sung through. Camerata member Vincenzo Galilei (Galileo’s father) suggested in 1581 that the musical quality of Greek tragedy was relevant to finding a more honest musical form for the 16th century. In 1598, the first performance of Jacopo Peri’s “Dafne” became what historians now mark as the original opera.

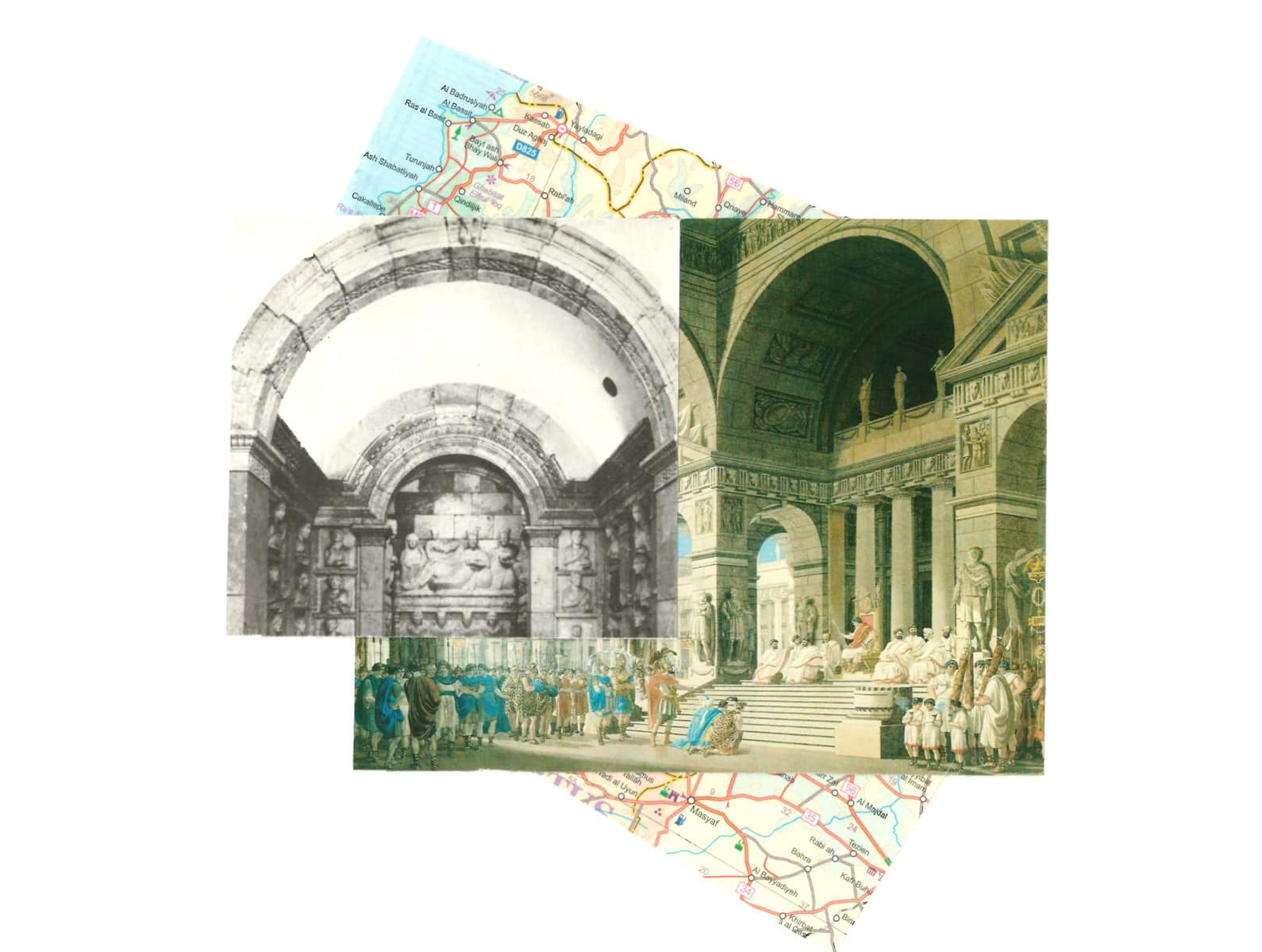

What Galilei and Peri didn’t know was that they were drawing on a tradition that the Greeks had borrowed from Mesopotamia. “The whole world was here: Europe, Africa, and Asia,” Mohammed, a resident in Athens’s Eleonas Refugee Camp, explained to me over tea one evening last October. “You can imagine that the Mediterranean was like a lake between these two continents…All civilizations, you can see them here on the coast of the Mediterranean. Syria, Greece, and Egypt.”

When I mention to Mohammed my interest in opera’s Syrian roots, he lights up and launches into a cultural resume for the Fertile Crescent (a pride I know well from my Syrian grandmother and her family). “The first alphabet, it was in Syria also. And also we have the first musical note. It was discovered in Syria, it was written on stone. His name is Ziad Ajjan, the Syrian musician who played it.” He shakes his head, puzzled when I ask him if he’s also a musician. “I’m an engineer.”

In the 1950s, archaeologists discovered a collection of clay tablets at the site of the ancient city of Ugarit (now Ras Shamra, Syria). Estimated at 3,400 years old, the tablets were studied by Assyriologist Anne Draffkorn Kilmer alongside musicologist Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin. One tablet referred to a tuning method for an ancient Babylonian lyre, presenting a combination of notes that were read as musical intervals. Another, surviving in fragments and known as H6, presents an ancient cultic hymn.

The relative obscurity of Hurrian, the tablet’s language, continues to leave specialists stymied by the precise meaning of the tablet in terms of its notational system. However, Drs. Kilmer and Duchesne Guillemin hazarded a best guess that it refers to a cyclical heptatonic scale. Musicologist Richard L. Crocker said of the first contemporary performance of H6, “This has revolutionized the whole concept of the origin of western music.”

The revolution lay in dispelling the myth that had fueled the Florentine Camerata: that harmony and music theory were born in ancient Greece. Moreover, the tablets gave a new source for both the format of lyrics paired with musical notation and the groundworks of Pythagorean musical theory. Mesopotamia had a 1,000-year head-start.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

History, much like nature, abhors a vacuum. The Greeks first occupied northwestern Syria in the 14th and 13th centuries BC, before returning in the 7th century. This second occupation became known to art historians as the Orientalizing Period, a time in which the aesthetic thumbprints of the Middle East and Northern Africa were left on jugs, urns, and vases. Greek myths trace their lineage to the literature and legends of Mesopotamia, which were appropriated by the foreign forces stationed abroad. This happened while the Greeks also foisted their culture onto their new subjects—in fact, it may have happened because of this imposition. In his book Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World, Dr. Nathanael J. Andrade explains that the Greek occupation led to many Syrians preserving their culture, beliefs, and rituals behind a veneer of classical Greekness. “Greekness (or Greek culture),” he writes, “was not a static, universal category. It was not always classical or homogenous.”

Given how much of the Babylonian empire migrated via the Tigris and the Euphrates and across the Mediterranean, the lineage of music theory found in Ugarit would also have traveled to Greece alongside the alphabet and mathematical principles. The cult song of Ugarit, interpretations of which include hand choreography that are considered to be gestures made in front of different gods, may have had an influence on the roots of Greek tragedy. Before there was theater, there were ancient cults, initiations to which were marked by rites known as mysteries.

The Dionysian Mysteries, which developed as early as 100 years into the second Greek occupation of Syria, celebrated the same god who would become associated with Greece’s first amphitheater. Known as the transgressor of borders, Dionysus was the intermediary between the gods and mortals. To be initiated into his cult was to overcome the fear of death.

Similarly, to be initiated into the Cult of Demeter and Persephone was to enter into the eternal river of life as it flowed from one generation to the next. Initiation was held in Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries involved beholding things done, shown, and said—a precursor to live performance.

The Florentine Camerata then brought the world of Greek mythology into what Dr. Britt-Mari Näsström of the University of Gothenburg describes as “a change of paradigm from the world of myth to an ethical dialogue between men’s world and the will of heaven.” We see this dialogue played out in many opera plots, from Monteverdi’s Ovid-based “L’Orfeo” to Mozart’s “Idomeneo.” It shouldn’t come as a surprise that a group of Italian artists and philosophers working to reintroduce a sense of morality into the zeitgeist would be attracted to art that focused on ethics in the face of catastrophe.

It would be disingenuous to say that music itself was invented in Syria, as archaeomusicologist Richard Dumbrill cautions me. The human body is the earliest instrument and we are walking, living, breathing manifestations of sound. Greek drama’s practice of singing for at least parts of a play could be seen as a sense of “giving voice” to our emotions, coming home to the body human amid the metaphysical catharsis of disaster.

What H6 and the other Ugarit tablets give us is the hypothesis that music theory originated in Babylonia. And we may just be scratching the surface. A 2006 publication of a cuneiform tablet in the Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society, referred to as CBS 1776, prompted a response a year later by Caroline Waerzeggers and Ronny Siebes, suggesting that the Neo-Babylonian tablet gives us the first documentation of the heptatonic scale. Dr. Dumbrill, who has students diving even deeper into line-by-line musical comparisons between Babylon and early music, has latched onto this theory. He has also criticized the early work of Drs. Kilmer and Duchesne-Guillemin, cautioning against interpreting Eastern idioms through a Western lens as a form of “supremacist musicology.”

“Their insistence at force-fitting a musical system into the Western model, and in this case with the ‘unconscious’ aim at accumulating Semitic musicology under the Occidental yoke…is one of the greatest oversights in the history of music,” he wrote in 2017, comparing Drs. Kilmer and Duchesne-Guillemin’s methods of interpreting the ancient tablets via Western musical models to translating “Old-Babylonian with a grammar of Mandarin. The manner in which systems are constructed, whether consciously or not, are part of the culture of a people and must be unveiled with the utmost respect and without linkage to theories of later cultures as this would lead to colonialist unification.”

At the same time, to paraphrase Kierkegaard, the history of music can only be understood backwards. Listening to recordings of H6, it’s easy to hear how the music, if not its origins, has traveled. One recurring motif sounds like a presentiment of “God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen,” a result of what in Western music theory we attribute to a descending tetrachord—the walkdown of four sequential notes on a scale. Keep this scale minor (as in the case of that familiar Christmas carol), and you have what is known as a lament bass—also referred to as the “Phrygian tetrachord.” This name references the Greek-allied kingdom of Phrygia, which was both a conqueror of the Hurrians and regarded as the origin point of Greek musical theory.

Lament also connects ancient Greek drama to the roots of Italian opera. It became the vehicle for catharsis, an emotional climax followed by a denouement, usually towards the end of the tragedy and accompanying a character’s death. Monteverdi would dip his toe into the same waters most famously with the aria “Lamento della ninfa” from his madrigals, but also in his first opera “L’Arianna,” now lost save for the aria “Lasciatemi morire” (recorded by everyone from Anne Sofie von Otter to Jewel). Monteverdi’s time in Venice also didn’t see the composer in a vacuum: The city spent the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries in cultural exchange with Aleppo, regarded as modern Syria’s musical capital.

Dumbrill’s idea of “colonialist unification” gives some context to the other question I had asked Mohammed in Eleonas: How has Syria remained largely out of the lexicon of music history, outside of the Middle East, over the last six decades? He shrugged sadly in response.

When H6 received its modern-world premiere in 1974, it was covered on Page 1 of the New York Times. The story of Syria creating the world’s first notated song has since resurfaced in various contexts, from a recent BBC Travel feature to an arrangement of H6 by Nico Muhly that was performed at the Guggenheim. However, as Dr. Duchesne-Guillemin wrote in one paper, “errors die hard.”

Centuries of opera plots paint Middle Eastern and Muslim characters as backward barbarians, even as their heroic Western counterparts sing in styles that are comparable to Arabic musical modes like maqam (a melodic form of improvisation which bears strong links to the fireworks of bel canto’s musical cadenzas). When singers today are praised for emotional sincerity or musical intensity, two of the three criteria for evaluating the authenticity of Arabic music as described by Jonathan Holt Shannon in Among the Jasmine Trees: Music and Modernity in Contemporary Syria are being used.

While these elements (known as ṣidq and ṭarab in Arabic) aren’t documented as part of the Ugarit tablets, they do seem to have evolved from the same thread. In 2011, Dr. Dumbrill presented his interpretation on H6 at the Dar al-Assad Opera House as part of the Oriental Landscapes Conference to a group of leading maqam musicians. On first listen, the performers began to instinctively hum along and suggest modifications to the intonation based on their musical knowledge. “These musicians, after 3,000 years, recognized H6 as part of their heritage,” Dumbrill explains.

Saying that the Middle East is at the roots of our culture is, in 2019, effectively trying to swim upstream. I went from writing this piece in the shadow of Tucker Carlson’s old interview footage asserting that “white men” were suffering a lack of credit for “creating civilization” to editing it in the wake of a terrorist attack on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand that left 50 people dead—and an anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant manifesto in its wake. The manifesto shows how easily Orientalist and supremacist rhetoric still travel in an age of Muslim travel bans.

As Edward Said writes in the introduction to Orientalism, “European culture gained in strength and identity by setting itself off against the Orient as a sort of surrogate and even underground self.” Or, as Jehad Abusalim tweeted in March, the fallout around U.S. congresswoman Ilhan Omar was “the perfect example of how Westerners like to discipline the ‘oriental subject.’ For them, the oriental subject is never ready to lead and have opinions, when she/he makes mistakes, they are not given a chance.” In writing about Congresswoman Omar, Abusalim could have just as easily been talking about the character of Bey Mustafà in Rossini’s “L’italiana in Algeri.” The bare-bones context of the opera’s plot, centering on an Algerian who tires of his wife Elvira and seeks a new lover in an Italian woman, is almost identical to Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.” Yet, because Mustafà is an Algerian rather than a Spaniard, he is a barbarian instead of a seducer.

“Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s 1973 staging of this battle of the sexes, framed by Rossini and his librettist as an abduction drama,” wrote the New York Times of the Metropolitan Opera’s last revival of “Italiana” in 2016 (opening just weeks before the election), “may be the silliest and most stereotype-laden production in the Met’s repertory. But it’s still very funny—irresistibly so, as I found out.”

Iranian multidisciplinary artist and librettist Niloufar Talebi got less slack. After her first opera, she was offered a second commission—under the condition that she not write a work set in Iran or with Iranian characters in order “to prevent emotional involvement getting in the way of my craft,” as she wrote last year for San Francisco Classical Voice. “I doubt whether an American librettist of European descent would be told not to set her opera in Texas or Idaho. It felt like xenophobia,” she added. Errors, most notable among them the error of supremacy, die hard.

It’s still extremely difficult to get to Syria (although Dr. Dumbrill plans to go back this spring). So I go to Greece. Much like the characters of the first dramas, I feel like an exile trying to find a sense of home on foreign shores, or a deeper meaning to this obsession I have with my DNA — somewhere between Sophocles’s “Antigone” and Wagner’s “Parsifal.” To go to Greece is to at least find some entry point in the cyclical continuum of history.

What began as an interchange between Syria and Greece expanded into a circular pattern, not unlike the circle of tunings first documented in ancient Babylon. The circle has expanded, from ancient Syria to ancient Greece; from ancient Greece to Renaissance Italy; and from ancient Greek tragedy to the current Syrian diaspora. Perhaps it’s impossible to go home again. Perhaps we can never step in the same river twice. Perhaps, too, with all of the talk about how to build a future for opera while remaining in a chasm between ignorance and denial of its past, we’re living out the Talking Heads song: We know where we’re going, but we don’t know where we’ve been.

Before getting to the Eleonas camp, I drive out to Eleusis, 11 miles north of Athens. The city’s archeological site includes the Telesterion, where the Eleusinian Mysteries were apparently held. It’s close to the museum’s closing time, and I’m the only one there standing in a palimpsest of history.

An informational plaque says that initiates to the Cult of Demeter and Persephone would drink a psychoactive elixir known as kykeon. The goal was to grasp the infinite, and to merge individual self with collective unconscious. The Telesterion provided the gateway for this experience of life beyond death, and for a unified whole. The actual ingredients of kykeon are up for debate, but one theory posits that it was a proto-ayahuasca made from the herb peganum harmala. Otherwise known as Syrian Rue. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.