What, exactly, is a fuckboy? When I asked people on what remains of classical Twitter to tell me about their favorite fuckboys in opera, the responses I received showed that, even after a nearly-decade-old debate around the word’s manifold meanings and usage, we’ve yet to reach a consensus.

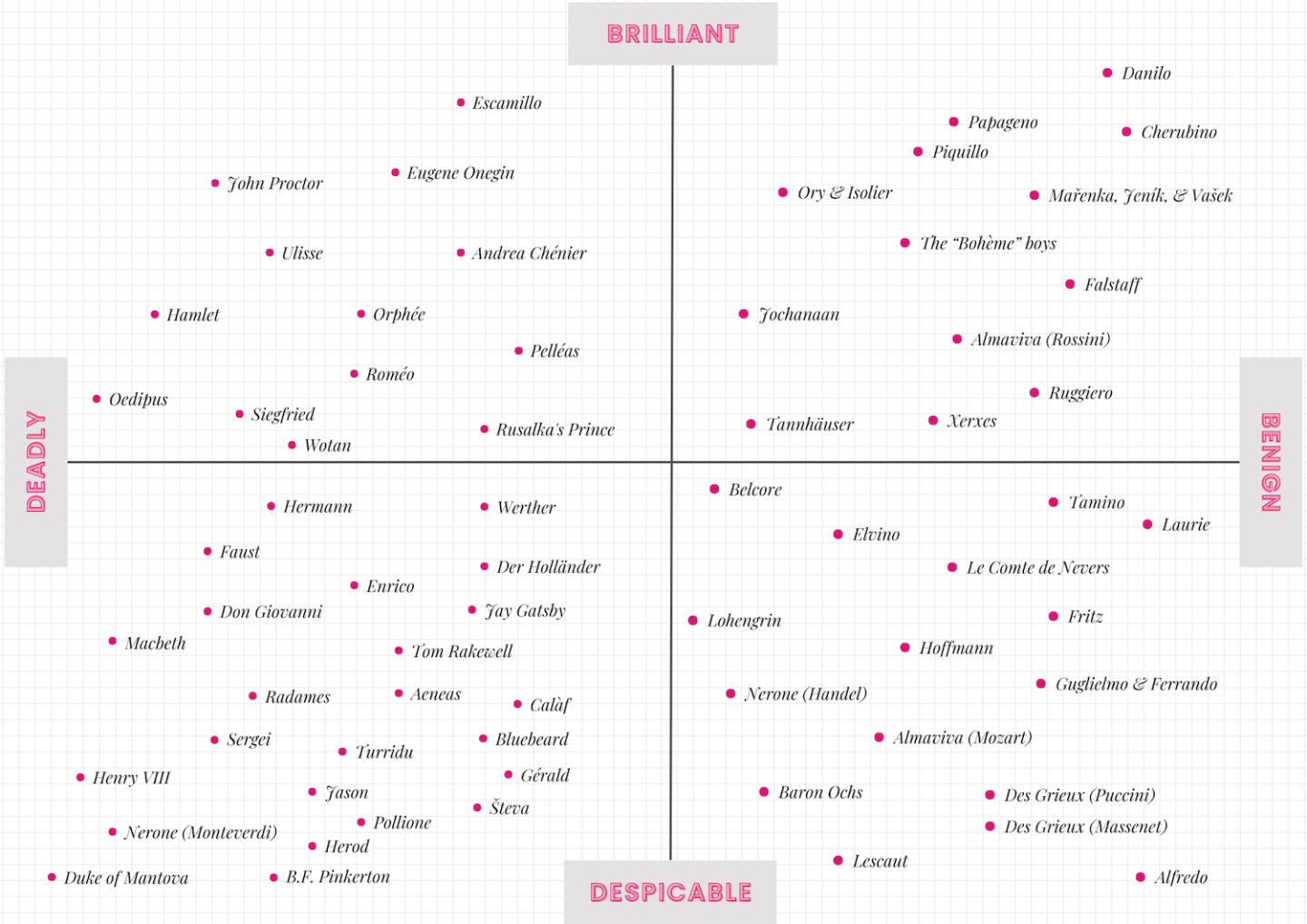

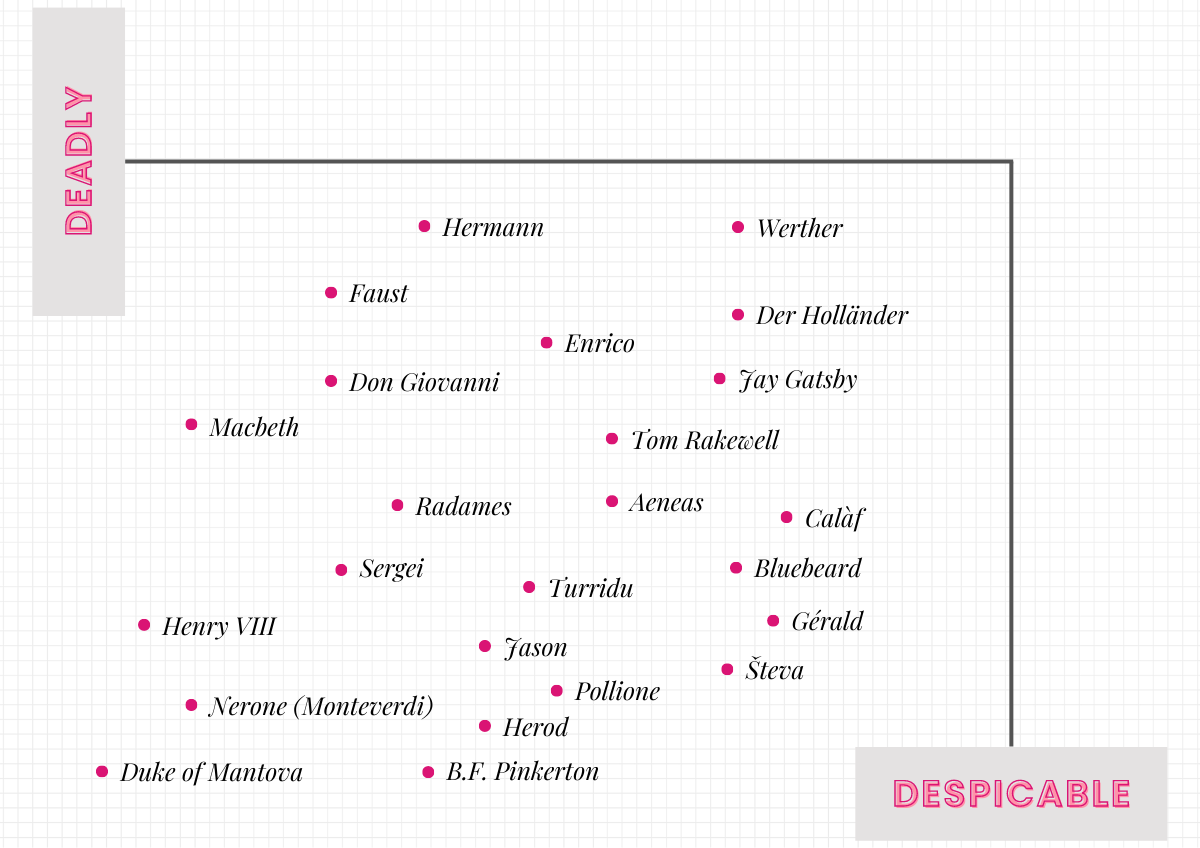

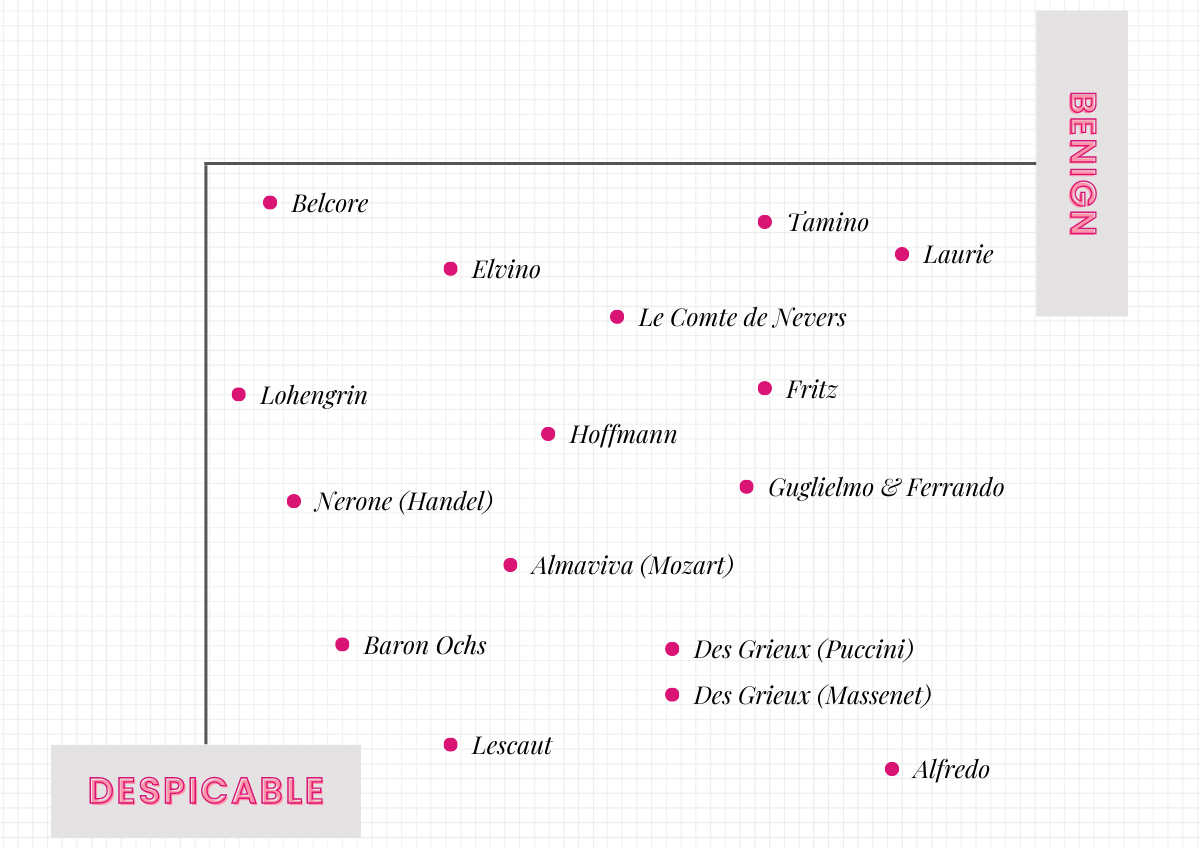

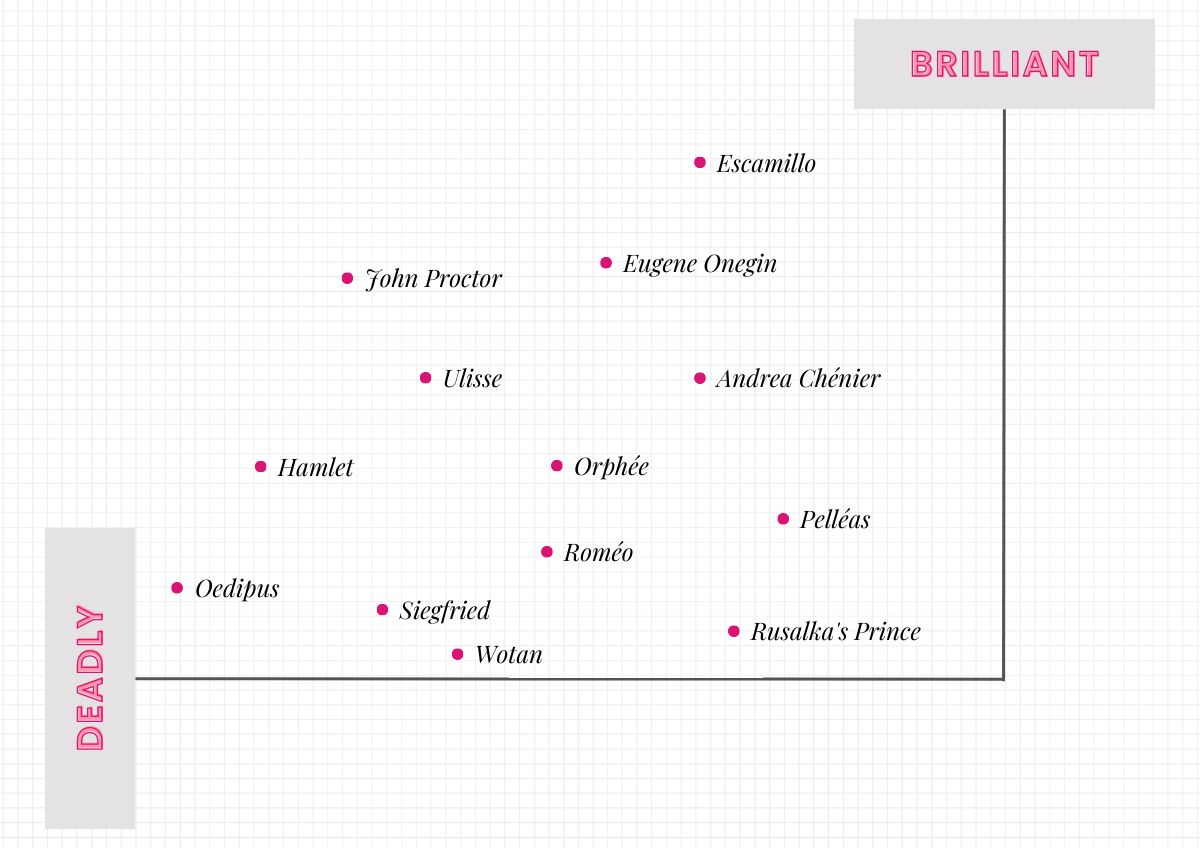

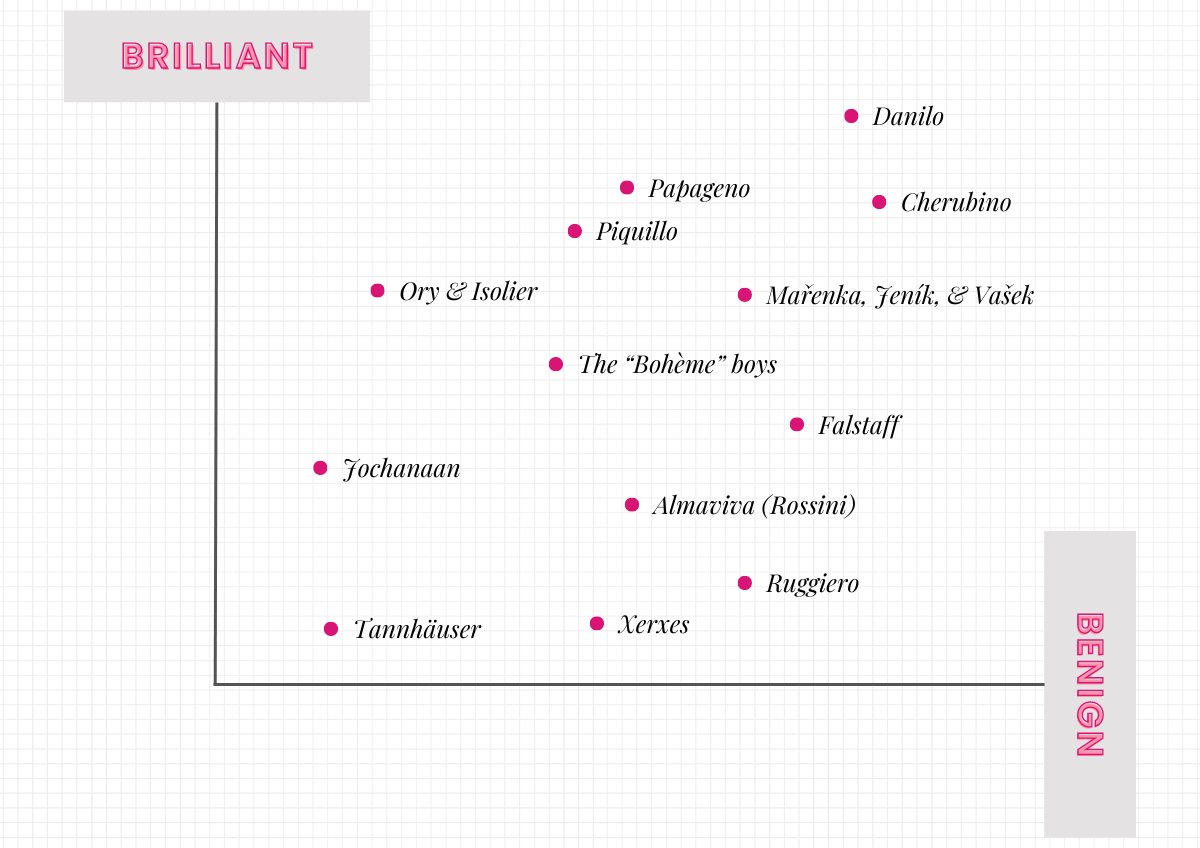

I’m not here to define the fuckboy. As Potter Stewart famously said, I know it when I see it. And I see it a lot on the opera stage. What follows is a scientific, though not exhaustive, survey of opera’s fuckboys representing the culmination of a lifetime of having my heart broken by opera characters, and about 20 years of obsessively reading Susan McClary. To further break things down, I’ve arranged these characters on a matrix that ranges on the X axis from Deadly to Benign, and a Y axis that—in a nod to New York Magazine’s Approval Matrix—ranges from Despicable to Brilliant.

Deadly & Despicable

The Duke of Mantova (“Rigoletto,” Giuseppe Verdi, 1851)

The quintessential fuckboy of opera is a monarch who leverages power towards sleeping with every woman in his court (willingly or otherwise), killing any man who objects, and then singing about how women are the real problem… as the woman he seduced and arguably raped under false pretenses gets stabbed in his place.

B.F. Pinkerton (“Madama Butterfly,” Giacomo Puccini, 1904)

Fuckboys and imperialism go hand-in-hand, as we’ll see throughout this list. Pinkerton is perhaps the most despicable, not only for his treatment of Cio-Cio San, but also for the larger geopolitical context.

“Consider it this way: What would you say if a blonde homecoming queen fell in love with a short Japanese businessman?” one of the characters in David Henry Hwang’s “M. Butterfly” asks another, after the latter professes his love for Puccini’s opera. “He treats her cruelly, then goes home for three years, during which time she prays to his picture and turns down marriage from a young Kennedy. Then, when she learns he has remarried, she kills herself. Now, I believe you would consider this girl to be a deranged idiot, correct? But because it’s an Oriental who kills herself for a Westerner—ah!—you find it beautiful.”

Nerone (“L’incoronazione di Poppea,” Claudio Monteverdi, 1643)

“Del senato e del popolo non curo,” Monteverdi’s Nero sings: I care not for the Senate or the people. Shortly after this, he exiles his first wife, orders his tutor to kill himself, and marries his mistress. This is what happens when your dick conquers all.

Henry VIII (“Anna Bolena,” Donizetti, 1830; “Henry VIII,” Camille Saint-Saëns, 1883)

If we go into the venn diagram of operas based on historical figures and historical fuckboys, we’re going to be here all night. Henry VIII can do much of the lifting for his comrades.

Herod (“Salome,” Richard Strauss, 1905)

One of the key characteristics of a fuckboy is their insistence on a sexual relationship on their terms. (Many of the listicles I consulted for this piece also warned about those who explicitly request nudes.) Herod is what happens when a fuckboy grows up to be a fuckman. For those of you who would dispute his credentials, just remember: Strauss wrote him as a tenor role.

Pollione (“Norma,” Bellini, 1833)

A role that smells like Axe Body Spray and bad decisions.

Jason (“Medea,” Luigi Cherubini, 1797)

Jason walked so Pollione could run, but at least he’s upfront when he abandons Medea.

Števa (“Jenůfa,” Leoš Janáček, 1904)

We hate Laca for slashing Jenůfa’s cheek out of jealousy, which: fair. But it turns out he knew exactly what drove his brother Števa: That disfiguration is enough to drive Števa away from Jenůfa—who just had his baby. I’m willing to bet that 90 percent of the accounts Števa follows on social media are women.

Gérald (“Lakmé,” Léo Delibes, 1883)

Fuckboy colonialism.

Sergei (“Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk,” Dmitri Shostakovich, 1934)

After all the hell you put Katerina through, you’re going to steal her stockings as well?

Turridu (“Cavalleria rusticana,” Pietro Mascagni, 1890)

Team Santuzza.

Bluebeard (“Bluebeard’s Castle,” Béla Bartók, 1918)

The epitome of a fuckboy who only wants to hang out with you when it’s dark.

Radames (“Aida,” Verdi, 1871)

“Aida” exists as a sort of inverted “Madama Butterfly,” with the fuckboy-imperialist returning home and doing a lot of navel-gazing over a self-constructed love triangle. Somehow he convinces Aida to put her infatuation with him over her own country, people, and life. Such is the fatal allure of a fuckboy.

Aeneas (“Dido and Aeneas,” Henry Purcell, 1689)

How sincere do you think Aeneas is being when he repeatedly tells Dido he’ll offend the gods and stay with her in Carthage?

Calàf (“Turandot,” Puccini, 1926)

With an aria like “Nessun dorma” and his willingness to put his life on the line for Turandot’s love, you’d think that the Calàf is the opposite of a fuckboy. But think about it: The climax of the aria isn’t about love or Turandot herself, it’s about how he’s going to win. When she reiterates she has zero interest in him, he negs her into submission like a petulant child.

She’s out there trying to run a country while breaking intergenerational trauma, and speaking in poetic lines: “Son la figlia del cielo, libera e pura. Tu stringi il mio freddo velo, ma l’anima è lassù!” I am the daughter of heaven, free and pure. You may grab for my icy veil, but my spirit soars! And all he can do is repeat that her iciness is a lie and that he wants her to be his. When he kisses her, she responds for all of us by asking: How did you win?!

Also: How many mirror selfies do we think are on this guy’s phone?

Macbeth (“Macbeth,” Verdi, 1847)

Not every fuckboy relies on women exclusively for sex. Sometimes they also need them for regicide. Kate Beaton captured this essence of Macbeth’s fuckboy-ery in a succinct three panels:

Tom Rakewell (“The Rake’s Progress,” Igor Stravinsky, 1951)

There’s a reason why Tom’s is one of the most-deserved deaths in opera. Not only does he shatter the innocent Anne Truelove, he also fucks with the general public with a business venture that does more harm than good.

Don Giovanni (“Don Giovanni,” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1787)

Do I really need to explain this one?

Jay Gatsby (“The Great Gatsby,” John Harbison, 1999)

If you need this one explained further, I’ll refer you to the podcast Fuckbois of Literature, which has an entire episode dedicated to The Great Gatsby.

Harbison’s version of the opera (commissioned by the Met to celebrate James Levine’s 25th anniversary with the company) was rushed for its first outing. The world premiere was its first complete run-through, leaving flaws exposed and the work to languish in semi-obscurity. Which is a shame, as the moral that you can’t repeat the past always carries an extra punch with opera audiences. (What if the real fuckboy was inside of us the whole time?)

Enrico (“Lucia di Lammermoor,” Gaetano Donizetti, 1835)

I once saw a bad Google translation of a website describe Enrico as Lucia’s “spending and spent” brother, a phrase that fits him so accurately, and one that speaks to his fuckboy nature. He doesn’t have any romantic entanglement in the opera, but relies heavily on his sister (almost to an incestuous degree) to bail him out of his financial issues.

Der Holländer (“Der fliegende Holländer,” Wagner, 1843)

I have a feeling that Daland is also a fuckboy (he’s pretty quick to trade his only daughter for the Dutchman’s fortune, and the absence of Senta’s mother is questionable at best). But the Holländer is unquestionably so, as seen in the finale. Women generally don’t go around flinging themselves off of the nearest fjord out of the conviction that they can fix a non-fuckboy.

Faust (“La damnation de Faust,” Hector Berlioz, 1846; “Faust,” Charles Gounod, 1859; “Mefistofele,” Arrigo Boito, 1868)

People talk a lot about the “Werther” effect, the (somewhat debunkable) idea that Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther led many readers, male and female, to emulate its eponymous protagonist by killing themselves in poetic fashion.

Less frequently discussed, but more demonstrably true, is that Goethe’s Faust ignited an 18th-century fad for the Mädchen Gretchen. Women braided their hair in a 16th-century style that emulated Goethe’s historical setting. Men lusted after the idea of these medieval, virginal creatures who existed solely to fulfill their desires. George Sand satirized the phenomenon, and the larger Romantic Fuckboy Epoch, in her 1841 novel, Horace.

Hermann (“The Queen of Spades,” Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1890)

You’d think that characters like Hermann and Werther (see below) don’t qualify as fuckboys because they’re the ones pursuing unavailable women. Yet Hermann’s love for Liza isn’t so much love as infatuation; he doesn’t even know her name. This is even more pronounced in Tchaikovsky’s opera compared to Pushkin’s original story. In the latter, Liza abandons Hermann after he kills her grandmother, marries someone else, and lives out the rest of her days without further incident. In the opera, Hermann abandons her, leaving her to plunge to her death in the Neva, believing all is lost. This critical bit of dramatic alteration highlights the fuckboy rising in Tchaikovsky’s Hermann.

Werther (“Werther,” Jules Massenet, 1892)

A rarely-used but premium-level fuckboy move: tricking a woman who doesn’t reciprocate your feelings into giving you a set of pistols so you can “die by her hand.” Even more premium: doing such a bad job of shooting yourself that the same woman has to watch you die.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Benign & Despicable

Alfredo (“La traviata,” Verdi, 1853)

I need a supercut of every time Alfredo has gotten slapped in a production of “Traviata.”

Des Grieux (“Manon Lescaut,” Puccini, 1893)

Less despicable than Massenet’s Des Grieux (see below), mostly because Puccini doesn’t include the St. Sulpice or casino scenes in his work.

Des Grieux (“Manon,” Jules Massenet, 1884)

Puccini’s Des Grieux is no angel, but Massenet’s is a hundred times whinier and more reliant on Manon as his meal ticket.

Lescaut (“Manon Lescaut,” Puccini and “Manon,” Massenet)

But it’s Manon’s cousin-brother (Massenet casts him as the former, Puccini the latter) who literally pimps her out to cover his gambling debts.

Baron Ochs (“Der Rosenkavalier,” Strauss, 1911)

The benign version of Strauss’s Herod.

Count Almaviva (“Le Nozze di Figaro,” Mozart, 1786)

Exercising droit du seigneur is just being a fuckboy with a noble title.

Nerone (“Agrippina,” George Friedrich Handel, 1709)

As horny as Monteverdi’s, but needs his mommy to do everything for him.

Guglielmo and Ferrando (“Così fan tutte,” Mozart, 1790)

These two argue over who has the more faithful girlfriend like Patrick Bateman and his colleagues having a pissing contest over their business cards. And that’s just the first scene. The fact that their experiment shows how interchangeable they are only serves to confirm their fuckboy-ery.

Hoffmann (“Les contes d’Hoffmann,” Jacques Offenbach, 1881)

Patron saint of the poets-to-fuckboys pipeline.

Lohengrin (“Lohengrin,” Richard Wagner, 1850)

Many fuckboys keep the women they’re seeing a secret. Keeping their name a secret from the woman they marry is next level.

Fritz (“Der ferne Klang,” Franz Schreker, 1903)

The final line of the opera is from Greta, the woman Fritz abandons for art, and sums it all up: “Fritz! Ach Fritz, was ist dir?” Fritz, what’s wrong with you?

Le Comte de Nevers (“Les Huguenots,” Giacomo Meyerbeer, 1836)

Nevers is one of only two Catholics in “Huguenots” who refuse to participate in the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, which is a point in his favor (unfortunately that gets him killed by his own offstage before the final scene). But he makes this seemingly brave decision mostly because he would prefer to spend his weekends drinking with his boys, “forgetting everything except pleasure.”

Elvino (“La Sonnambula,” Bellini, 1831)

When the notary asks Amina about her dowry, she says she brings only her heart. “Ah,” Elvino replies to his fiancée. “But the heart is everything!” Tell that to the girl you dumped for Amina, Elvino.

Laurie (“Little Women,” Mark Adamo, 1998)

“Laurie sucks. He’s a fuckboy. We all know it. We didn’t have the word for it until recently, but he is a fuckboy,” Karen Han said in a roundtable following Greta Gerwig’s film adaptation of Little Women. As if to hammer home this point, Adamo opens his own adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel with the revelation that Laurie, rejected by Jo, has married her sister Amy.

Tamino (“Die Zauberflöte,” Mozart, 1791)

Speaking of Mozartean fuckboys announcing themselves right out of the gate, Tamino needs to be rescued from a serpent by three ladies, and his reliance on women doesn’t let up. And yes, his silent treatment of Pamina is one of the tests Sarastro puts him through, but it also nearly leads to her suicide.

Belcore (“L’elisir d’amore,” Donizetti, 1832)

When Adina breaks off her engagement with Belcore to marry Nemorino, he responds: “Peggio per te! Pieno di donne è il mondo, e mille e mille ne otterrà Belcore.” Too bad for you. There are plenty of women in the world, and thousands and thousands of them will get to have me. Quod fuckboy demonstrandum.

Deadly & Brilliant

Wotan (“Der Ring des Nibelungen,” Wagner, 1869-76)

“Fuckboy is not a dating style,” writes Alana Massey, “so much as a worldview that reeks of entitlement but is aghast at the prospect of putting in effort.” Wotan is ruler of all the gods but… how much does he actually do in the “Ring” Cycle, compared to what he attempts to gain? Yeah. That’s what I thought.

Siegfried (“Siegfried” / “Götterdämmerung,” Richard Wagner, 1876)

It takes a special kind of fuckboy to bring about the twilight of the gods.

Oedipus (“Oedipus Rex,” Igor Stravinsky, 1927)

To be fair, Oedipus vows to save his people from the plague that is, well, plaguing them. What he doesn’t know is that the plague is there because he killed his father and married his mother. Fuck around and find out.

The Prince (“Rusalka,” Antonín Dvořák, 1901)

At least he dies in this version. As he does, Rusalka captures the essence of her unnamed prince’s fuckery with the final lines of the opera: “For your love, for that beauty of yours, for your inconstant human passion, for everything by which my fate is cursed, human soul, God have mercy on you!”

Roméo (“Roméo et Juliette,” Gounod, 1867)

Juliet’s nurse was onto something when she told her to marry Paris after Romeo was banished. He begins the piece in love with Rosaline, quickly pivots to Juliet, kills her cousin, and eventually embroils her in an unofficial suicide pact. Gounod also gives him a page, which makes things even worse. Roméo having an added intermediary should have sorted out all of the miscommunication in Shakespeare’s text.

Pelléas (“Pelléas et Mélisande,” Claude Debussy, 1902)

“Qu’allons-nous dire à Golaud s’il demande où il est?” Mélisande asks Pélleas after losing her wedding ring in a well during a slow-burn seduction between the pair. What will we tell Golaud if he asks where it is?

“La vérité,” Pélleas responds, like an operatic Timothée Chalamet, “la vérité.” The truth.

Orphée (“Orphée aux Enfers,” Jacques Offenbach, 1858)

To be honest, all of the Orpheuses register on the fuckboy spectrum. But Offenbach’s is the one that has to be bullied by Public Opinion into going down to the underworld to rescue Eurydice. It’s a rich text.

Hamlet (“Hamlet,” Ambroise Thomas, 1868)

The fact that Thomas’s Hamlet survives and the opera culminates in Ophelia’s burial only makes him more of a fuckboy.

Ulisse (“Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria,” Monteverdi, 1640)

Monteverdi gives Odysseus a pass on this by focusing on the second half of The Odyssey, and making this opera about the triumph of constancy and virtue (effectively the inverse of “L’incoronazione di Poppea”). But Odysseus’s long exile is predicated on his status as a fuckboy. Conversely, his ability to get home is predicated on his status as a fuckboy. We really do contain multitudes.

Andrea Chénier (“Andrea Chénier,” Umberto Giordano, 1896)

I love a Howard Zinn-reading fuckboy who refuses to perform poetry on command, but he’s still a fuckboy.

Eugene Onegin (“Eugene Onegin,” Tchaikovsky, 1878)

Tatiana: *writes an epic and searingly gorgeous love letter*

Onegin: lol k

(Also, if you disagree with me over placing Onegin in Brilliant versus Despicable: SHUT UP, I CAN FIX HIM.)

John Proctor (“The Crucible,” Robert Ward, 1961)

John’s affair with a teenage girl leads to the Salem Witch Trials. When his wife, Elizabeth, sings, “John, grant me this: You do not know a young girl’s heart,” you feel it. Redeemed by an 11th-inning spiritual breakthrough.

Escamillo (“Carmen,” Georges Bizet, 1875)

“In recent years I’ve come to see ‘Carmen’ as an opera about how you’re better off with an entertaining fuckboy than a jealous cop.”—Marissa Skudlarek

Benign & Brilliant

Tannhäuser (“Tannhäuser,” Wagner, 1845)

In an ideal world, Venus and Elisabeth get together and turn the Venusberg into a commune for women recovering from all of the fuckboys in Wagner’s other operas. But Tannhäuser just barely crosses the threshold from Despicable to Brilliant because “Dir töne Lob” is undeniably a bop.

Xeres (“Xeres,” Handel, 1738)

A tree-hugging fuckboy.

Ruggiero (“Alcina,” Handel, 1735)

Given the sheer number of his operas and their recurring dramatic tropes, Handel is a composer whose fuckboys merit their own ranking. But Alice Coote’s Ruggiero in particular is elite-level.

Jochanaan (“Salome”)

“He clearly leaves towels on the floor. And what a neg, ‘Du bist verflucht.’”—Das Konzept, with a “Salome” staging I want to see.

Count Almaviva (“Il Barbiere di Siviglia,” Gioachino Rossini, 1816)

Less threatening than what he grows into in “Le Nozze di Figaro,” but the whole “I’m a poor student in disguise” schtick places Rossini’s amiable hero in the same pool as the Duke of Mantova. Let’s talk about his often-cut final aria, “Cessa di più resistere.” Is it about the triumph of love? About his feelings for Rosina and the future he wants to build with her? Of course not. It’s about how much better he is than Bartolo. He does deliver the final verse to Rosina, but addresses her as an “infelice vittima.” Did Almaviva see the rest of the opera beforehand? Because Rosina not only seemed pretty happy (even given the shitty and pretty lechy guardianship situation with Bartolo), but also was no victim. She was taking control of her future as much as—if not more than—Almaviva and would have likely been fine on her own if he never came around.

Also, watching Rockwell Blake sing “Ecco, ridente in cielo” as a child gave me unrealistic expectations for the rest of my romantic life.

Falstaff (“Falstaff,” Verdi, 1893)

I’m all here for a fuckboy whose only endgame is to have someone pay for his bar tab.

Rodolfo, Marcello, Schaunard, and Colline (“La Bohème,” Puccini, 1896)

Described by my friend Kate as “one singular fuckboy, like Voltron,” the boys of “Bohème” are adorable but also messy. (Though props to Colline for selling his coat in a bid to save Mimì’s life.) “I love those boys so much,” Kate adds, “but part of growing up is realizing, ‘I have dated them and cannot be in that life again.’”

Mařenka, Jeník, and Vašek (“The Bartered Bride,” Bedřich Smetana, 1866)

These three fuckboy one another—and their entire town—into a happy ending. The kids are all right.

Ory and Isolier (“Le Comte Ory,” Rossini, 1828)

Vying for the same woman while disguised as nuns? Big fuckboy energy. Credit to Bartlett Sher’s staging at the Met, however, in which both men seem at least marginally invested in the Countess Adele’s own sexual gratification.

Piquillo (“La Périchole,” Offenbach, 1868)

Too broke to afford a marriage license, ultimately gets married while blackout drunk. As his girlfriend-cum-bride sings in Act II, “my God, men are so stupid.” It’s like “Bohème,” minus the TB.

Cherubino (“Le Nozze di Figaro”)

It’s rare to see a fuckboy come into their own as a fuckboy in real time, but that’s the brilliance of Mozart and Da Ponte.

Papageno (“Die Zauberflöte”)

His pairing with Papagena is proof that every pot has a lid. Even a fuckboy pot.

Danilo (“Die lustige Witwe,” Franz Léhar, 1905)

A fuckboy with a heart of gold whose entrance aria is all about how he’s a fuckboy. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.