If you’d like to drive an ice-pick through your eye but are short on equipment, the New York Times comments section is often a good virtual substitute. Case in point: The 700-plus responses to the paper’s coverage of the Metropolitan Opera’s decision to focus future seasons on more new works and living composers, citing sold-out performances for recent runs of Terence Blanchard’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” and Kevin Puts’s “The Hours” against lackluster sales for war horses like “Don Carlo.” While Peter Gelb told the Times that this represents “a big shift in terms of opera singers themselves, embracing new work and understanding that this is the future,” some fans offered counterpoints. “I’m pretty sure the singers, if not the audience, will at some point rebel against having to spend their limited career time singing contemporary junk,” wrote one commenter.

What’s missed by those who object to this new direction for the Met—as well as by many who support it—is the fact that this isn’t strictly new for the company or its singers. Contemporary works and living composers were integral to the company’s first few decades, when its singers sang as many new works as they did old (even more, in some cases). In the first 20 years of its history, it presented as many American premieres of contemporary works. In the 1910s alone, it gave 13 world premieres.

Many of these new works weren’t destined for long shelf lives. In a way, this makes them more interesting as microcosms of their era. It also suggests the need to do more than one new work a season: Treating each commission like it’s going to be the next repertory warhorse misses the point of creating an opera that speaks to the present moment. (Since 2000, the Met has performed an increasing number of contemporary works, but it’s only given four world premieres—and one of them was a pastiche cobbled together from a handful of Baroque operas and a libretto that rhymed “treetops” with “treetops.”)

Each of these nine works were brought to the United States and/or the opera stage at large for the first time by the Met, often by composers who were in the audience for those first nights, and provide a window into the strange and wonderful world of the company’s first 50-ish years of new works. Some would go on to become repertoire staples. Others would be written off as “contemporary junk.” The first entry did both.

Richard Wagner: “Mild und leise wie er lächelt” from “Tristan und Isolde” (1859)

Some of the Met’s best historical premieres are those that subvert their critical receptions—good, bad, or indifferent. “For once Wagnerites have it all their own way,” opened a unbylined New York Times review of the Met’s U.S. premiere of “Tristan und Isolde.” Or, as the Times critic put it, the “first performance in America of a work not wanted outside of Germany, and not too often there.”

The anonymous critic went on to say it would be “absurd” to think that the work, which opened at the Met on December 1, 1886 (three years after the composer’s death), would go on to be anything special or appeal to “serious” audiences. It had, as they put it, “no further significance.”

“Tristan und Isolde” has, since then, been performed 486 times at the Met alone. By the time the Met’s original Isolde, Lilli Lehmann, made this recording in 1907, it had bowed more than 75 times with the company. Gustav Mahler made his Met debut conducting the work the following year.

Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha: “Diana von Solange” (1891)

In the 1890-91 season, the Met gave the American premieres of three contemporary operas: Alberto Franchetti’s “Asrael,” Antonio Smareglia’s “Il vassallo di Szigeth,” and German Prince Ernest II’s “Diana von Solange.”

Franchetti’s work opened the season and starred three then-unknown singers, including the tenor Andreas Dippel, who would go on to co-lead the Met from 1908 to 1910. This was a risk—as one person said of the present-day Met’s decision to open future seasons with new works, would “The Hours” be a success without its three star-level leads? Yet, at least according to the Times, it was a success: “The fact that the operatic institution of the day has acquired force and independence was adequately demonstrated last evening,” opened the gray lady’s review.

The other “novelties” of the season were not as lucky. The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was not the first royal to try their hand at composition, but he may be among the worst. The company’s then-general manager, Edmund C. Stanton, was allegedly hopeful that getting in the Duke’s good graces would earn him a decoration. Reportedly it did, but he never wore it: “Diana von Solange” failed so spectacularly that it was pulled after its second performance and Stanton was fired. But even this work had some admirers: 300 fans showed up to what would have been the opera’s third performance (now replaced by Beethoven’s “Fidelio”) with a petition demanding for the run to be reinstated. And while no recording of the work exists, Franz Liszt wrote two rhapsodies on some of the opera’s main themes and motifs.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski: “Na kwiatowe łany opadają cienie” from “Manru” (1901)

“Manru” was the 25th American premiere that the Met gave, importing it less than nine months after its world premiere in Dresden. It was based on Józef Ignacy Kraszewski’s 1853-54 novel, The Cottage Outside the Village, which unflinchingly depicted discrimination against the Romani in Poland.

“The discussion of the first performance of the opera is too recent to admit of the addition today of significant comment on the musical achievement of the composer’s intent. We shall have further opportunities of hearing and studying this work,” wrote one reviewer.

Spoiler alert: We didn’t. At least not in the early 20th century. “Manru” disappeared from the Met after the 1901-02 season and its life since then has largely been relegated to Paderewski’s native Poland. A recent production from the Polish National Opera (streamed via Operavision) makes the case for the work’s enduring relevance and appeal.

Umberto Giordano: “Amor ti vieta” from “Fedora” (1898)

In 1903, Heinrich Conried assumed the helm as general director of the Met, and it was under his watch that the company brought many works that would become repertoire staples—for the house and for the wider industry—to the U.S. for the first time. This included Wagner’s “Parsifal” (a scandalous production for a work that was intended to never be seen outside of Bayreuth), Humperdinck’s “Hansel and Gretel,” Puccini’s “Manon Lescaut” and “Madame Butterfly,” and Strauss’s “Salome” (which, as the Tribune raged, “disgusts its hearers”—though even that critic had to acknowledge that the performance was sold out and raised $22,000 for the company—roughly half a million dollars in today’s money).

Like many of these new works, “Fedora”—which bowed for the first time in the U.S. on December 5, 1906—was also an opera based on a familiar piece of pop culture: Victorien Sardou’s play of the same name had made waves in New York performances starring Sarah Bernhardt. Reviewing “Fedora,” the Times called Conried’s focus on new works “unprecedented.” That’s saying something, as the company had no shortage of premieres before this one.

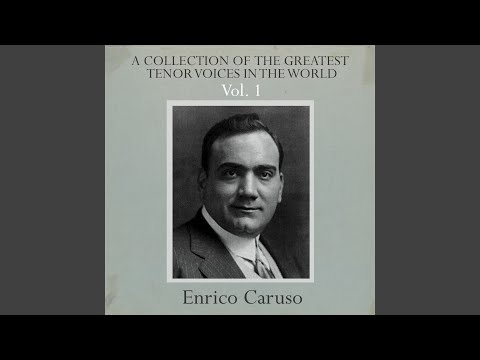

This recording predates the Met by a few years, but features one of the production’s stars: Enrico Caruso. The composer accompanies at the piano.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Giacomo Puccini: “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano” from “La fanciulla del West” (1910)

The Met’s investment in Puccini—including the U.S. premieres of “Butterfly,” “Manon Lescaut,” and “Tosca”—paid off with its first world premiere, which tasked the composer with writing a distinctly “American” tale. The closest the company has come to this sort of a relationship of multiple premieres in recent history is Nico Muhly, whose “Two Boys” (2013) and “Marnie” (2018) were both Met co-commissions with English National Opera.

A Herald review of “Fanciulla”’s maiden voyage serves as a precursor to the company’s recent success with works like “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” and “The Hours,” reflecting not only on the artistic merits of the work, but also its social and financial success:

The event had been looked forward to as socially one of the most brilliant in the history of the house, and the result justified expectation. An audience as large and as brilliant as that which is wont to assemble for the [first] night of the season followed the performance with ever growing interest. The opera was presented at double prices, ranging from $10 for orchestra seats down to $3 for admittance.…The evening was a climax so far in what the directors of the Metropolitan Opera House have done for grand opera in this city. To procure a new opera for the repertoire is in itself an achievement. To have that novelty performed here for the first time on any stage means even more; and when the opera is the work of the composer of “La Bohème,” “Tosca,” and “Madama Butterfly” and is the first Italian grand opera based on an American subject, the event assumes great significance.

Reginald De Koven: “The Canterbury Pilgrims” (1917)

“At last,” raved The Brooklyn Eagle, “the policy of producing original operas in English at the Metropolitan has scored a profitable success and there is on that stage an opera in English which the general public will run to instead of running away from…a stirring comic opera with a charming and sometimes dominating sentimental element, which promises to be widely popular.”

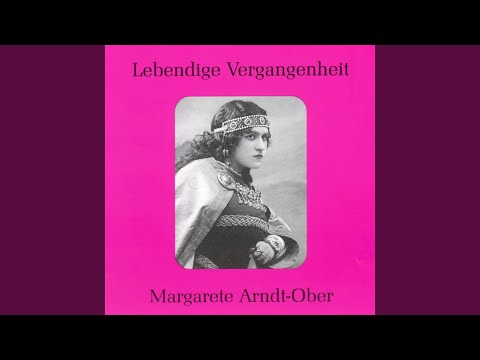

Unfortunately, the prolific American operatic composer Reginald De Koven’s “The Canterbury Pilgrims” opened at the Met shortly before the U.S. entered World War I. In fact, the U.S.’s involvement was announced in the middle of a performance of De Koven’s work, with word spreading like wildfire during the final act. The performance was paused for the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, under the baton of Austrian-born conductor Artur Bodanzky, to perform a spontaneous rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” As the Wife of Bath, the house’s star contralto, Margarethe Arndt-Ober (once described admiringly by Caruso as “the German she-devil”), tried to continue the performance after that, but collapsed onstage in a dead faint.

That was the end of “The Canterbury Pilgrims,” a work whose early triumph was dashed by bad timing. A recording was never made of the work, so I’ll leave you with a performance by Arndt-Ober, who in the 1910s was part of many American premieres at the Met, including “Der Rosenkavalier” and “Boris Godunov.” Her Met career was also a casualty of world events. Her contract, along with most of the company’s other German singers, was suspended for the following season due to the war, a move that was common with the flood of anti-German discrimination in the U.S. at the time (even those who had no connection to the German government). Arndt-Ober sued the Met for breach of contract and, while many of her peers were able to work with the company again following the Armistice, she was not. Her last performance with the company, given a few days after “The Canterbury Pilgrims” ended its run, was as Marina in “Boris Godunov.”

Charles Wakefield Cadman: “Spring Song of the Robin Woman” and “Ojibway Canoe Song” from “Shanewis” (1918)

By far one of the most fascinating premieres the Met has given was “Shanewis” in 1918. Composer Charles Wakefied Cadman had an anthropological interest in Native American music, living on both Omaha and Winnebago Nation reservations to study with their musicians and further researching music from the Osage, Pawnee, and Iroquois traditions.

For 25 years, Cadman toured the U.S. and Europe, giving lectures on his research. Often, these lectures featured Muscogee singer Tsianina Redfeather Blackstone. Eventually, Cadman and his librettist, Nelle Richmond Eberhart, began to work in close collaboration with Blackstone on “Shanewis,” which was based on Blackstone’s stories of growing up on the Muscogee Reservation in Oklahoma, as well as many of the issues that she saw her fellow First Nations facing (issues that Blackstone would continue to address in her career as an activist until her death in 1985 at the age of 102).

“Shanewis” premiered at the Met in 1918 to 21 curtain calls, and touched on topics like the Trail of Tears when that legacy was still a lived experience for many Native Americans. Blackstone herself was at the premiere, and performed the work in later productions around the U.S. The New York Times called the premiere “something like a new Declaration of Independence, as far as concerns American opera,” and noted that, “under the sparkling froth” of the society notables gathered for the new work, “there could be felt the dark current of [the United States’s] past dealings” with Native Americans. In 2023, there are obviously discussions to be had surrounding cultural appropriation and white saviorism. But imagine for a moment the effect this opera had on some of New York’s richest residents in 1918, which must have been seismic enough for even the Times to clock it.

Ildebrando Pizzetti: “Fratelli in povertà! Chi correrà più ratto?” from “Fra Gherardo” (1928)

The thing with doing so many new works is that it’s a numbers game. “Tristan,” “Fanciulla,” and “Canterbury Pilgrims,” were all successes (with varying definitions of the word), but for each of these, you’re going to run up against a handful of “Diana von Solange”-style failures.

That’s what happened with the 1929 U.S. premiere of Ildebrando Pizzetti’s “Fra Gherardo,” which was quickly imported from its world premiere at La Scala the previous year. “This music is essentially sterile,” wrote the New York Herald Tribune. “It is music of the will, of aesthetic piety, and good intentions.”

Just what the road to hell is paved with. Still, failure is a vital part of the artistic process. At the very least, it can make for fantastically bitchy reviews.

Louis Gruenberg: “Lord Jesus, hear my prayer” from “The Emperor Jones” (1933)

According to the New York World Telegram, “one of the largest audiences the Metropolitan Opera House has ever held”—at least within the company’s first 50 or so years—was for the world premiere of Louis Gruenberg’s “The Emperor Jones,” which opened on a Saturday afternoon in the early days of 1933.

Starring a blackfaced Lawrence Tibbett in the title role, Gruenberg’s adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s wildly popular play of the same name (a vehicle for Paul Robeson) had originally been slated for the Berlin Staatsoper, but the rise of the Nazis meant that an opera by a Jewish composer about a Black man who fashions himself into a tyrannical dictator, takes over an entire country, and ultimately shoots himself when he feels his ill-gotten regime collapsing around him, while prophetic, was not likely to go down well with Hitler’s party. It got a second life in the U.S., and a champion in Tibbett. You can hear his recordings of the work’s dramatic aria, when the title character is confronted with the consequences of his actions, but watching this recital performance by an early-career Reginald Smith, Jr. is far more electrifying in its full-blooded pathos. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.