- András Schiff: “J.S. Bach: Clavichord” (ECM)

- Keith Jarrett: “Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach” (ECM)

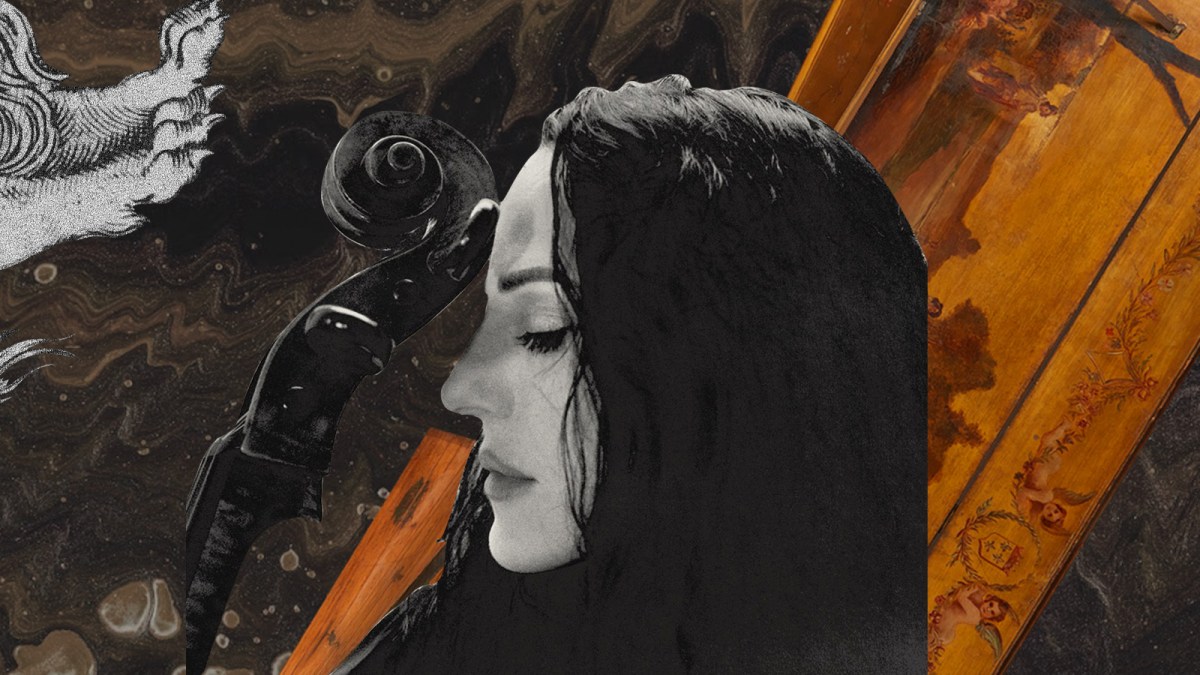

- Maya Beiser: “Infinite Bach” (Islandia Music)

As the landscape of Twitter continues to become more gnarled and Mad Maxian, are those who remain becoming more revanchistly retrograde? At this point, between the algorithm and the audacity, you’d think no tweet could still be so remarkable as to invoke a pile-on. Especially now that the app is limiting the amount of tweets non-paying users can see in a day. (The devolution will be monetized.)

I learned a few weeks ago that András Schiff’s Bach is still a live wire, at least for a small corner of Classical Twitter. “Look, I like Bach, I like András Schiff,” I wrote, “but do I really need an album that’s just 90 minutes of him playing Bach’s clavichord music?” For a few hours at least, I was in my own version of the Juilliard scene from “TÁR,” in which I was an unlikely Zethphan D. Smith-Gneist, and a group of people I know by avatar but not in real-life formed a multi-headed hydra-Tár. This, as Ben Miller put it, was a hill worth dying on.

I’m going to miss that site when it eventually and inevitably crumbles like Valhalla.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

It’s not that I dislike Schiff’s new album for ECM, which he recorded in 2018 but, with links to “our noisy, troubled times” and the act of “playing alone,” carries added subtext in this new-ish decade. Listening to the entire 83 minutes and 51 seconds all in one go is simply…a lot. There’s only so much oasis water you can soak up before your eye starts to wander back to the desert. Yet the clavichord—described by Schiff as both “a most gentle creature” and “a demanding and unforgiving teacher”—can be both oasis and desert in one. A quieter cousin of the piano and harpsichord, its notes don’t evaporate into the ether, instead resonating long after the string has been hit or plucked. Clavichord tangents, narrow brass blades that look like the tip of a flathead screwdriver, graze the strings as long as the player has pressed down. When they lift their fingers, the notes stop, suddenly and completely. The effect is like sound absorbed into fresh snow.

It also doesn’t leave much room for the performer to hide, though for Schiff—who, in the 1980s, led a revolution by reclaiming Bach for the piano versus the harpsichord—this is a feature rather than a bug. Take the “Aria di Postiglione” from the “Capriccio sopra la lontananza del fratello dilettissimo” (BWV 992). You can hear Schiff play the work on a contemporary piano in a 1989 concert from Munich, and it’s unsurpassingly lovely: lyrical without being overindulgent, insightful without being navel-gazy.

Three decades later, Schiff’s recording of the same work on clavichord is like a completed oil portrait compared to the piano version’s initial pencil sketch. The aria’s recurring three-note rejoinder takes on more meaningful delivery in the gradations of the instrument, and the dynamics between the lower and upper register feel more like a two-hander by Tom Stoppard or Harold Pinter than a casual conversation. Schiff accentuates the crispness of the clavichord’s tangents in the subsequent variations on the theme, and it girds a cantabile effect that truly sounds like an aria, with all of the folds and contours of a natural voice.

It’s one of the many moments on Schiff’s recording that make you hit pause in order to soak up what just happened. (Another favorite: The second of Bach’s 15 Inventions, BWV 773, ends with a pluck that sounds like Jerry Douglas making a dobro cameo.) It’s as much a testament to the instrument as it is to Schiff’s playing. In a 1989 interview with the Los Angeles Times, he told Mark Swed: “We should just listen to the interpretation and the message of the music and forget about the instrument.” Three decades later, we have the inverse—the instrument is the message.

As Bach biographer Christoph Wolff points out, that was deliberate for the composer, who paid special attention “to the idiomatic qualities of the individual [keyboard] instruments.” Beyond that, as Bach contemporary and fellow composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt recalled, the idiosyncrasies of the instruments themselves also colored Bach’s compositions: “Not only does Bach play a slow, singing adagio with the most touching expression (to the embarrassment of many instrumentalists who could imitate the voice with far less difficulty on their own instruments), he sustains, even in this tempo, a note six eighths long with all degrees of loudness, both in the bass and the treble. But this is perhaps possible only on his very fine Silbermann clavichord for which he has written sonatas in which long sustained notes occur.”

What I love about that Reichardt quote is that it suggests a certain futility: Why play Bach on piano if he wrote the work for clavichord? Why play Bach on the clavichord if it’s not that Silbermann clavichord? Why play Bach at all if each performance is doomed to fail—as so many other instrumentalists have, according to Reichardt? (“He knows that it’s always the question that involves the listener,” Tár says of Bach during her Juilliard masterclass, before making this, too, into a question: “It’s never the answer, right?”)

“I’d heard the sonatas played by harpsichordists, and felt there was a space left for a piano version,” Keith Jarrett says of CPE Bach’s “Württemberg Sonatas,” which he recorded in 1994 and is now, 29 years later, releasing for the first time (also on ECM). The sentiment encapsulates Schiff’s own revolutionary performances of Carl Philipp’s father on a modern (“ ”) instrument at around the same point in time. The performance itself is a bittersweet listen given the last few years: Following a Carnegie Hall concert in 2017, Jarrett was noticeably absent from the stage, both in classical concert halls and in jazz spaces where Jarrett made a comfortable home as an improviser without rival. In October 2020, Jarrett finally gave fans an answer as to why: He’d had two strokes in the first half of 2018, and said it was unlikely he would perform in public again. Following his second stroke, he spent some time in a nursing facility where he tried “to pretend that I was Bach with one hand” in the facility’s piano room.

At a time when Jarrett no longer considers himself to be a pianist, going back three decades to a portrait of the musician as a young(er) man—manifestly a pianist—is a jarring experience and adds an emotional depth to the recording. This is augmented by Paul Griffiths’s liner essay, which reads more like flash fiction than program notes: “Too much light, the old man thinks, but does not say. Not for him to say. Not for him to comment on his son’s apartment in a palace. He himself is the servant of a church. Cheaper candles.”

Jarrett was 49 when he recorded these sonatas—younger than Carl Philipp (who was in his 30s when he wrote them). Jarrett is now older than the 60-something Johann Sebastian Bach in Griffiths’s narrative. Listening to his performance now, for all its understated brilliance of technique and cadmium-hued tones, I wonder where he was when he recorded it. Did he pretend to be Bach the elder, or Bach the younger? It’s a question that hangs over the entirety of the album for me, and while it’s not the one that Jarrett sought to ask in 1994, it becomes indelibly part of the listening experience in 2023.

Among the 10,000 questions that he could have been asking, I doubt that Bach was giving much thought to binaural beats in between his siring of 20 kids. But, as a composer invested in the specifics of acoustic experience, I can imagine that a modern-day Bach would be trawling Google Scholar for whitepapers.

As someone certified in sound practition (a fancy way of saying I paid way too much money to a for-profit meditation studio to sit through a dozen or so sound baths and be told “the sound you hear is the sound you hear”), I have heard enough beneficial claims of binaural beats to rival those attached to the benefits of tuning music to 432 Hz. But binaural sound—the way your brain makes up the difference if you’re hearing music pitched at two different frequencies, creating a trippy but soothing effect—is at least an audible phenomenon, and one grounded in decades of science; one of the topic’s landmark studies was published in 1950. And, rather than coopting the effect into a panacea that will heal everything from cancer to the Holocaust (one of my sound practitioner colleagues believed in the latter), it’s nice to see how something like binaural technology can be layered into a musical warhorse.

As a founding member of the Bang on a Can All-Stars, Maya Beiser has always approached music as a toaster to be pulled apart so as to learn how it works. Her 2019 album, “delugEON,” cast the slow movements from Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons” against sounds of melting Antarctic ice caps, NASA recordings of wind on Mars, Moroccan desert dunes, and ocean squalls. Her cello recording of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” incorporated her own heartbeat when she found her med-school student son’s stethoscope, thought, “This is basically an amplifier, right?” and wondered how she could work with it musically.

If anyone would give serious thought to what they had to say in recording a work like Bach’s Cello Suites, it would be Maya Beiser, who recently told Tidal that she had never considered recording or performing the work because of how often it was already done. The catalyst for her changing course was the space: In 2021, feeling the lockdown-induced strain of being in one place for too long, Beiser and her husband bought a house in the Berkshires. The property included a converted barn that seemed built for Bach.

Sound engineer Dave Cook, Beiser’s fearless copilot for many of her projects, worked with the space as an instrument in itself, recording Beiser’s performance from various distances within the barn. The result isn’t an Enya-ified experience; it’s not programmed to be the de facto soundtrack for hashtag-mindful, hashtag-highvibe soundbaths. Instead, the effect is like that slightly dizzy feeling you get from those TikTok videos that instruct you to turn your phone horizontally and listen to a sound that finds harmony in the middle ground between two pitches. Much like the phenomenon that Schiff describes, the outside noise shuts off and the overtones and reverberations of Beiser’s barn form a space to listen. In the familiar opening movement of the first Suite, Beiser’s warm, companionable tone grabs you like a family member meeting you at an airport arrivals hall, mirroring the ability of Bach’s music to point to some place specific on the map of your emotional landscape and say with red-arrow confidence, “You are here.”

Even more than Schiff’s album, “Infinite Bach” is, in its entirety, a substantive text—more than two-and-a-half hours of Bach does indeed sound infinite. Perhaps it’s less noticeable due to the tendrils of the cello as an instrument and the specific mix that Beiser and Cook achieve; it’s like a lake that’s cool enough to be refreshing but warm enough to not threaten a shock to the system, easy to dip in and out of over the course of a hazy afternoon. The deliberate arrangement of Bach’s Cello Suites is also a time-tested tradition of pace and movement, a journey from points A to Z. In both cases, however, it may be that the recording is an imperfect medium for the experience—though it’s the most perfect imperfect medium we have. The courses of both Schiff’s and Beiser’s repertoire unfold continuously with Bach’s metric feet. Like the title brother in Bach’s “Capriccio sopra la lontananza del fratello dilettissimo,” we come and depart as listeners. Dropping in on specific works on each recording creates a distilled and demarcated amount of beauty that’s easier to savor from all angles. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.