In Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie, there’s a portrait of Emperor Francis I of Austria (1792-1806) that bears a marked resemblance to King Charles III. Unsurprisingly, given how prone royals are to marrying within their own family, the pair are distantly related. At times, working on this playlist, which charts the royal lineage into which Charles officially steps this weekend with his coronation, felt like a similarly incestuous iteration of the Pepe Silvia meme.

Fitting, too, is the reminder that many of these entries provide of how miserable most royals are—onstage and in real life. Heavy is the head that wears the crown. Or, to quote Tracy Jordan: “Heavy is the head that eats the crayons.” In some cases, I think the royals listed below did both.

Grażyna Bacewicz: “Przygoda Króla Artura” (1959)

Whether King Arthur was or was not a real person and ruler of England remains a topic of debate. But Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz’s radio opera deserves a spot on this list for its “Love for Three Oranges”-level of absurdity, a frenzy that resolves in introspection and upending of Arthurian legend. “What do all women want?” Arthur is asked by the (doubtlessly historically accurate) Giant of Mont Saint Michel. Arthur’s life hinges on the question, yet he cannot reach consensus by asking the women he encounters. A witch finally reveals the answer, one for the ages: The right to choose.

Judith Weir: “King Harald’s Saga” (1979)

35 years before she became the Master of the King’s (formerly Queen’s) Music, Judith Weir wrote this ten-minute monodrama for soprano—and no accompaniment—that demands its singer take on multiple roles in retelling the story of Harald of Norway’s failed invasion of England and defeat at the Battle at Stamford Bridge on September 25, 1066. But his opponent, King Harold II of England, would die in combat himself a few weeks later in the Battle of Hastings.

André Grétry: “Richard Coeur-de-lion” (1784)

Grétry’s account of King Richard the Lionheart’s imprisonment by Austrian Duke Leopold V (and subsequent rescue by French troubadour Jean de Nesle) was a sparkling and sumptuous landmark of opéra-comique. Its only flaw was that it premiered just five years before the French Revolution, which put a damper on its popularity. Contrary to Mel Brooks’s Louis XVI, it’s not always good to be the king.

George Benjamin: “Lessons in Love and Violence” (2018)

In the Vita Edwardi Secundi, a 1326 chronicle of the reign of England’s Edward II, the anonymous author writes: “I do not remember to have heard that one man so loved another… and our king was incapable of moderate favor.” This refers to Piers Gaveston, Edward’s favorite and presumed lover.

That presumption isn’t confirmed, but Vita Edwardi Secundi isn’t the only contemporary documentation of Edward’s love for Gaveston, often at the expense of his wife, Isabella of France (both her allowance and the dowry from 12-year-old Isabella’s marriage to the 23-year-old Edward were often diverted to Gaveston). This eventually led to Gaveston’s murder, Edward neglecting both his home life and duty to country, and Isabella orchestrating a coup with her lover which would lead to her receiving the uncharitable nickname “The She-Wolf of France.” Isabella would persuade Edward II to abdicate in favor of their young son, Edward III, and she (along with her own lover, Roger Mortimer) would reign as regent until he claimed power in his own right. Edward II died in prison, shortly after renouncing the throne, either from illness or—as one legend goes—from murder via having a hot poker shoved up his rectum. This in and of itself lends credence to the theory that Edward and Gaveston were lovers: As Dana Schwartz, host of the history podcast “Noble Blood,” notes: “No one shoves a red-hot poker up someone’s butt because they’re upset that he’s such close platonic bros with another man.”

In an opera based on Christopher Marlowe’s dramatic adaptation of these events (“Edward II”), George Benjamin renders the homoerotic dynamic of this relationship explicit, while also crafting a multidimensional character out of Isabella, equal parts wolf and quarry. When Edward II learns of Gaveston’s death, he blames his wife, demanding that she show her face as the wretch he believes her to be. Isabella, who attempted to fulfill the role prescribed to her by society while her twice-her-age husband degraded her in not-so-secret favor of another man—all before she was a teenager, mind—snaps: “Here is my face,” she responds. “What have I ever hidden?”

Gaetano Donizetti: “L’assedio di Calais” (1836)

In depicting Edward III’s siege of Calais, an opening salvo in the Hundred Year’s War, Donizetti and librettist Salvatore Cammarano depict Isabella as Edward’s wife, not mother. Potato, po-incest.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Gustav Holst: “At the Boar’s Head” (1925)

Gustav Holst wrote a handful of operas, some more successful than others. His 1923 work, “The Perfect Fool,” crashed hard at Covent Garden, labeled by music critic and lecturer Hugh Ottaway as “beyond redemption.” He followed that up with “At the Boar’s Head,” a combination of Shakespeare’s “Henry IV,” Parts 1 and 2, focusing on the future King Henry V’s friendship with Sir John Falstaff. “It is tempting to see this as a creative response to a sense of having failed,” writes Ottaway, who then dispels the notion: “The starting point seems to have been completely spontaneous—a recognition that the dance tune he was looking at fitted some words he had just been reading in one of the Henry IV plays.” About as random an operatic origin story as the idea that certain people are ordained by god to rule nations.

Giacomo Meyerbeer: “Margherita d’Anjou” (1820)

Another “She-Wolf of France,” Margaret of Anjou was 15 when she was crowned queen consort to Henry VI—the only son of Henry V and the disputed King of France as well as England. At the time, she was described as “already a woman: passionate and proud and strong-willed.” That strong will would be a deficit for the young queen, whose uncle (Charles VII of France, also Henry’s uncle) contested his nephew’s claim to the French throne. In fact, Henry’s marriage to Margaret was an attempt at a peace treaty that never amounted to anything, except further dissatisfaction with Henry among his British subjects, especially as Margaret was married to Henry without a dowry: Instead, he gifted their uncle the French territory of Maine. Having already been declared unfit to rule in 1437, these 1445 nuptials did Henry no favors. In 1461, he was deposed, succeeded by Edward IV.

For her part, Margaret was a shrewd politician whose strong will filled a vacuum left by the mentally unstable Henry VI. From exile in Scotland and France, she lobbied for Henry VI to regain rule so that their son, another Edward, would eventually ascend to the throne as well. When Edward IV lost two key supporters, Margaret formed an alliance with them to re-throne Henry VI, who ruled again for just under six months before the death of the couple’s 17-year-old son in the Battle of Tewkesbury. Without a viable heir, Henry was imprisoned in the Tower of London where he himself died under mysterious circumstances. Margaret was imprisoned in England until she was ransomed by Charles II’s successor, Louis XI, and lived as a “poor relation” to the king in France for seven years before dying at the age of 52. Her legacy was left to Shakespeare, who has one character seethe towards a version of Margaret in “Henry VI,” Part 3: “Women are soft, mild, pitiful, and flexible; thou art stern, obdurate, flinty, rough, remorseless.”

All of this seems like the stuff of French grand opera. It was, in fact, in one of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s early operas, written roughly a decade before “Robert le Diable.” However, Meyerbeer abandons most of the facts more dramatic than fiction for a flimsy love triangle between a widowed Queen Margherita, a French nobleman and chief supporter for her (improbably) still-alive son’s claim to the throne, and his long-suffering wife. The drama feels convoluted and the end wraps up a bit too neatly, but that also means there’s a rich history waiting for a composer to get it right.

Giorgio Battistelli: “Richard III” (2004)

The ineffectual rule of Henry VI (who came from the House of Lancaster) renewed claims to the English throne from the House of York (including Edward IV), sparking the War of the Roses. This continued after Edward IV’s death, with the short-lived, uncrowned reign of Edward V, who disappeared from the Tower of London (along with his brother, Richard Shrewsbury) just before his coronation. Yada, yada, yada, we have Richard III.

Shakespeare also gives short shrift to the House of York and its final ruler, portraying him as a hunchback manipulator rather than a ruler who was seemingly competent but much maligned. That makes sense when you consider that Shakespeare was writing for an England under Queen Elizabeth, whose great-grandfather defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. History is, after all, written by the victors.

Giorgio Battistelli’s “Richard III” doesn’t break with this tradition. Written in Shakespeare’s image, Battistelli’s Richard is an unpredictable sociopath, manipulating other characters, the audience, and even at times the orchestra to his own advantage.

Camille Saint-Saëns: “Henry VIII” (1883)

Much in the same way the Y2K fashion trends of today are really a throwback to a period in the late ’90s in which we were milking the fashion trends of the late ’70s for all they had, manias seem to be cyclical. This would explain why our current (albeit waning) cultural obsession with the Tudors had its predecessor in the 19th century. Saint-Saëns was late to the game compared with Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti. But his slice of history comes first on the timeline in a jewel-toned drama, equal parts Renaissance ballad and proto-Wagnerian epic, about Henry VIII’s break with Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn. Perhaps the work, debuting at the tail-end of the 1800s compared to the first few decades, speaks to what Charlotte Higgins wrote for The Guardian in 2016: “Tudormania spawns more Tudormania.”

Even this work, which had a champion in Montserrat Caballé, seems to be respawning fans: A 2019 concert performance by Boston’s Odyssey Opera was released on Odyssey Records last summer. This summer, Bard Summerscape will make a case for the work with a new production staged by Jean-Romain Vesperini.

Gian Carlo Menotti: “La Loca” (1979-82)

Before we move through the Tudors, a brief sidestep into the life of Catherine of Aragon’s sister, Juana I of Castille. Known as Juana “La Loca” for perhaps self-explanatory reasons, Juana—much like her sister—suffered a similarly miserable marriage that led to her loosening grip on reality. Her marriage to Austria’s Philip the Handsome brought Habsburg rule into Spain, and produced Charles V (father to Philip II and grandfather to Carlos of Asturias—aka Verdi’s Don Carlo).

Following Beverly Sills’s triumph as all three of Donizetti’s Tudor Queens in the mid-70s, Gian Carlo Menotti wrote an opera based on Juana la Loca specifically for her, a work that, though flawed, gave her yet another blazing mad scene to sink her teeth into. After nearly half a century locked up in a convent, Juana, nearing death, asks her priest if God exists. “His love exists,” the priest replies, beneficently. “Do you promise?… Do you promise?… Promise… Promise,” she says, to no response. The final “Promise” is delivered with a “Lulu”-level scream that hints at how cursed a fate it is to be born a woman into royalty.

Donizetti: “Anna Bolena” (1830)

What happens after the action of Saint-Saëns’s “Henry VIII” is what, in terms of music history, happens before “Henry VIII,” with Donizetti’s dramatization of Anne Boleyn’s fall from grace and execution, here replete with one of the composer’s signature mad scenes. This not only corroborates documentation of Boleyn’s mental illness during her imprisonment, but also foreshadows Donizetti’s own psychotic breakdown, triggered by neurosyphilis, which would take place 16 years later.

Giovanni Pacini: “Maria, regina d’Inghilterra” (1843)

Odyssey Opera could easily string together the majority of the British royal lineage through its repertoire history. Case in point: Its 2019 production of “Maria, regina d’Inghiliterra,” Pacini’s adaptation of Victor Hugo’s play about Mary I of England, aka “Bloody Mary,” aka the daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, aka second wife to Spain’s Philip II.

Credit, too, to the bel cantists, who suffered no dearth of subject material from royal history combined with literary artistic license. Baritone Leroy Davis, who sang Ernesto Malcolm in Odyssey’s production, says of this plot: “You actually don’t know what’s going to happen at the end.” This is both a pleasant mindfuck (spoiler alert, Mary I died in 1858) and a throughline for many historically-inspired operas from this era, which abandoned AP test facts for stories that imagined the psychological and emotional resonances of characters whose destinies were seemingly to be emotionless godheads for the people they ruled.

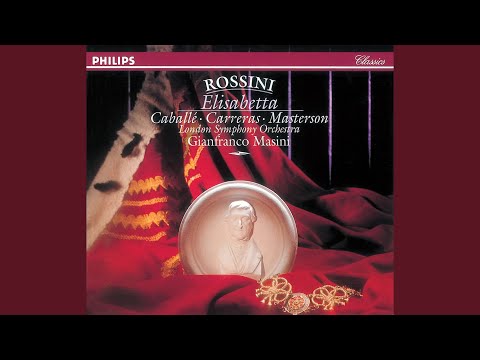

Gioachino Rossini: “Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra” (1815)

If you want to know how passionate Rossini was about the subject matter of Elizabeth I, all you need to know is that his overture to “Elisabetta” was recycled from “Aureliano in Palmira” (1813) and later used for “Il barbiere di Siviglia” (1816).

Benjamin Britten: “Gloriana” (1953)

Commissioned for the June 1953 coronation of Queen Elizabeth, Benjamin Britten’s “Gloriana” was eagerly anticipated, a means of cementing the link between Britain’s two Elizabeths that was invoked in the early days of QEII’s reign.

That anticipation went unsatisfied. “Everyone expected ‘Gloriana’ to be a tribute to the new sovereign—a glorification of Elizabeth I which would serve as a glorification of Elizabeth II and would ring up the curtain on a new Elizabethan age,” wrote one contemporary review in the New York Herald Tribune. “It turned out to be nothing of the kind. Instead of pursuing and elaborating the sweet fairy-tale mood which had been woven round the streets of London and in the nation’s press, Britten shattered it…by bringing to life the full-blooded, down-to-earth tragedy of Elizabeth.”

On the other hand, some moods were made to be shattered.

Giuseppe Verdi: “Don Carlo” (1867)

With so many members of the family still running around European society circles today (including Charles III himself), I often wonder what it must feel like to be a Habsburg at a performance of “Don Carlo,” watching the lives of your distant forebears enacted onstage. With so many operas exploring politics and power, it’s not a unique situation to this one opera or clan—Elisabetta in “Don Carlo” is the real-life sister of Marguerite in Meyerbeer’s “Les Huguenots.”

Perhaps, if given to reflection, they may consider how widely stories like Verdi’s (based on Friedrich Schiller’s play) miss the mark on reality. More likely, as inheritors of mythical power themselves, they know better than most to not let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Thea Musgrave: “Mary, Queen of Scots” (1977)

Based not on the Schiller text but rather a play by Peruvian writer Amalia Elguera, Thea Musgrave’s life of Mary Stuart focuses on the lose-lose position of many queens from this era. A sovereign in her own right, Mary is still pressured to give ruling power to her husband, Lord Darnley. Amid the crisis of her reign, Musgrave gives Mary a nuanced and deft soliloquy in which she wonders where she can turn and whom she can trust among her inner circle—“for I cannot stand alone.” Gaining in determination and resoluteness, she then realizes she “must stand alone” as the leader of Scotland.

Vincenzo Bellini: “I Puritani” (1835)

In what happened to be Queen Victoria’s favorite opera, the religiously-tinged English Civil War reaches the bel canto front in the form of Henrietta Maria, queen consort to the executed Charles I (Mary Stuart’s grandson). The tenor-hero Arturo agrees to rescue her from a similar fate, vowing: “You shall be saved, oh unhappy woman!” She makes it out of the opera alive, one of the rare happy endings for a royal on this list.

Peter Maxwell Davies: “Eight Songs for a Mad King” (1969)

As Benjamin Poore wrote of “Eight Songs” in last year’s Queen Elizabeth II playlist for VAN, “What is remarkable about ‘Eight Songs for a Mad King’ is the fragility of its central figure, and the tenderness with which the piece handles his collapsing sense of self, which seem in part related to the self-annihilating delusions of grandiosity entailed in the monarchist imagination.”

To be fair, George III also grew up learning of the rise and fall of the Plantagenet, Lancaster, York, Tudor, and Stuart dynasties before his own line, the House of Hanover, took rule in 1714. If that taught him anything, it was that history is cyclical. What’s more, even monarchs were just cogs in the historical machine. In that sense, a tree may as well be Frederick the Great of Prussia.

Bo Holten: “The Visit of the Royal Physician” (2009)

Parallels to George III are everywhere in “The Visit of the Royal Physician,” both the opera and the real-life events on which it and its source novel are based. Queen Caroline Matilda marries the Danish King Christian VII, whose birth was marked by Glück with an opera, “La Contesa dei Numi,” in which the gods of Mount Olympus debate who among them should be the princeling’s protector.

Greek gods are not the best insurance plan for a young monarch, and Christian’s childhood was particularly traumatic, a situation not helped by what some scholars today believe was schizophrenia. This was also not the ideal situation for Caroline Matilda, George III’s sister, to enter when she married Christian and moved to Denmark. However, her situation improved somewhat when she began an affair with Christian’s personal doctor, the progressive humanist Johann Struensee, who was soon able—with Caroline—to help enact progressive laws in Denmark through his influence over Christian.

“Many believe that when time is so limited that you should focus on the love story,” says “Visit” dramaturg and co-librettist Eva Sommested Holten, describing a number of the historical operas that precede this one on the list. “But then I wouldn’t find the story interesting. What’s interesting is that we have a mad king.” Sommested Holten adds that the Enlightenment aspect of the story plays a huge role in creating an opera with fully-fleshed characters: “The sense of responsibility [Streunsee] feels and the fact that a passage in history opens to him: Does he dare enter?” In a way, the characters in Holten’s world are trying in their own way to protect Christian VII, while also furthering the interests of the people he himself was born to protect.

John Corigliano: “The Ghosts of Versailles” (1991)

Most operas about doomed royals end with their deaths. John Corigliano’s extension on Beaumarchais’s “Figaro” plays goes into the afterlife with a post-guillotine Marie Antoinette. Given that the last queen of France was Queen Elizabeth II’s fourth cousin, four times removed, this lends an especially charged air to Charles and Camilla’s would-be visit to a protest-laden France in March. The visit, since postponed, was to have included a banquet reception at Versailles. Cue Teresa Stratas singing “They Are Always With Me.”

Robert Wilson: “A Letter for Queen Victoria” (1974)

Two years before “Einstein on the Beach,” Robert Wilson premiered a three-hour opera without singers so loosely related to Queen Victoria that it would make “Einstein” look like “Nixon in China.” Its 1974 run in Paris, shortly after its world premiere in Spoleto, Italy, featured Wilson’s 88-year-old grandmother, Alma Hamilton, dressed as the Grandmother of Europe, describing the regimen of pills she (Hamilton) had to take daily to “keep going”: three for diabetes, one for blood pressure, and two vitamins. Exactly what you would expect from Robert Wilson.

Einojuhani Rautavaara: “Rasputin” (2003)

No one can compete with Boney M in paying musical homage to the cat that really was gone. However, Rautavaara comes closest with his own mystical musical style—an uneasy neo-romanticism tinged with tumescent flirtations with serialism. Rautavaara’s retelling of the impossible-to-kill mad monk also parallels the fall of the Romanovs: “The night of suffering is here, the beginning of the end,” the chorus sings in the opera’s finale. Tsar Nicholas II and his family would die just over 18 months later.

This, too, would directly impact Charles III. Nicholas was first cousins and close friends with George V of England, Charles’s great-grandfather. The two looked so alike they were often mistaken for one another. Following the abdication of Nicholas and the arrest of him and his family, there was discussion of exiling them to England, a move that George V ultimately and reluctantly halted when he realized his own reign could be threatened by the political implications. Of the remaining Romanovs in Russia who were able to be evacuated, one was Grand Duchess Olga Constantinova, a first cousin once removed to Nicholas II and grandmother to the future Prince Philip—Charles III’s father.

Josh Spear: “That Woman” (2014)

Charles III’s sieg-heiling great-uncle, King Edward VIII, abdicated the throne after less than a year as king, and before his official coronation, in order to marry the twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson. With Edward’s brother, George VI on the throne, the order of succession shifted and led to both George’s daughter, Elizabeth’s, reign and now Charles.

Josh Spear tells the story of Edward and Simpson in a “Rashomon” style across three scenes. The first focuses on the unenthused reception to King Edward when he took the throne in 1936. The second tells the story from Edward’s perspective—a self-martyrdom in which he gives everything up for love and was so shunned by his family that cozying up to the Third Reich seemed like a necessity since they were the only politicians interested in him after his abdication. The final scene is dedicated to Simpson’s revision of history, spanning 1937—her marriage to Edward—and 1981—just a few years before her death, and the same year that Charles married Diana. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.