On February 13, English mezzo-soprano Alice Coote will perform the role of Mère Marie de l’Incarnation in Francis Poulenc’s opera “Dialogue des Carmélites” at the Zurich Opera. It’s her second production—and first set of full rehearsals—since the start of the pandemic, and there are still worries about COVID-19: The cast has made an agreement that they won’t socialize outside of their work at the opera house. For our meeting in an office at the opera, Coote wore a leopard-print dress, a smartwatch, and a KN95 mask, and took occasional breaks from our intense conversation to look at the clear sky or listen to a horn warming up.

VAN: The director of this new “Dialogue des Carmélites” is Jetske Mijnssen, a woman. In 2013, you told the New York Times that opera “is still a bit too nondemocratic,” maybe because it’s “a man’s world.” Is it different working with a female director?

Alice Coote: Absolutely. I’ve certainly noticed [Mijnssen’s] different view on this piece. I don’t think a male director would’ve come up with this way of doing it. Let that be judged. But also the experience of actually rehearsing it: There’s the nurturing quality. It may be just her, but it’s not autocratic; it lets people find things gently. It’s unilaterally democratic in the room.

I’ve noticed that about female directors. They don’t necessarily feel that they’re allowed to just say, “That was shit,” or “Kid, what the hell are you doing?” Society still tells them that they’re being a bitch if they do that. Not every male director would say that—but men wouldn’t feel that they were being a bastard for doing it.

LGBT: There’s no W in that. I’ve worked for 30 years and can count on one hand how many female directors I’ve worked with, how many female conductors I’ve worked with. Of course, there are women onstage. But the women have always had to behave a certain way. They won’t say, “This is too slow for me.” A woman would have to say, “Maestro, I’m not breathing,” and make a joke about the corset. The conversation is in its infancy right now, which is a crazy thing to say in 2022.

What do you mean when you say, “LGBT: There’s no W in that”?

My brother is transgender, don’t get me wrong. He’s been through hell, but he’s going on an amazing journey right now. I’m completely open to everything. I don’t know after all these years of playing men and women who I really am. I have questioned myself: What part of me is the male part of me, what part of me is the female part of me? What is truly me?

I’m getting off the [opera], but you’re not allowed to say anything to do with anything at all. Everything has to be so completely politically correct, except about women’s rights. We are still absolutely in a second-class position in every walk of life. We still have to pretend to be other than we are every day, and we still accept that every day. I’ve been doing it all morning. I’ve been doing Alice the female. We don’t have that innate power to be who we are. I’ve learned that from playing men.

So you feel like when you’re playing a man on stage, you have more power afterwards too?

I feel very liberated when I come offstage [after having played a man] for quite a while. It does affect how I feel when I go to the supermarket, or when I’m walking down the street. [As women], normally we don’t take up too much space. I’ve got my legs crossed here. [When I’m playing a man], I take this space. [She sits on the chair with her legs spread wide.] If I want sex with you, I’m going to have sex with you. I’m not saying every man is like that, but when I come out of the theater, I’m taking up half the space that I was taking up when I was on the stage.

It’s not just physical: It also goes for my opinions. All of these opera stories don’t have women expressing their opinions. Even in the most dramatic monologue about life and death, the women aren’t expressing their opinion in the way that men are. We’re still required to look beautiful. It’s really hard to feel like what you’re saying is important if you’re required to look beautiful while you’re doing it.

That is true in the “Dialogue des Carmélites,” where the nuns go willingly to the guillotine at the end. There’s a sort of idealized female meekness to it.

It’s a weird one though, because this is the only opera I’ve been in that really hasn’t got sex in it. Sex is there, but we are actually not being required to be sexual, which is incredibly liberating. Playing this role is the nearest I’ve got to playing a man.

Because you’re not required to be sexual?

Yes. My character is really interesting: I see somebody who’s followed something all her life, who believes in it implicitly. But what do we all truly believe in? How far do we go for it? I don’t think the nuns really know why they go to their deaths. Is it to stay together, to honor each other? I don’t know if it’s a belief in God. These are big questions.

How can you translate such ambivalent feelings for the audience from the distance of the opera stage?

It’s in the score. Then of course you have to live it for real. I’ve spent the first two or three weeks in tears the majority of the time. Poulenc wrote these amazing little painterly miniatures, complete little moments of truth. Then the curtain goes down and there is no answer.

Do you empathize with the fairly traditional religiosity of the opera?

I was brought up as—I suppose you’d call it atheist, but I don’t like labels. I don’t believe in anything called God. Although I’ve been known to talk to God in my darkest hours, so I’m a complete hypocrite. That’s the beauty of it: The piece is about the contradictions and the fallibility of human beings. The people you think are going to fail are the ones that come through. [La Mère Marie de l’Incarnation] talks a big game all the way through the show, and then at the end of it, where is she? I don’t identify with the religious thing, but I think religion is a true example of how much every human being needs saving. We all need saving. We’re all terrified.

“Dialogue des Carmélites” may not be a sexual work, but I think you’re in the category of opera-singer sex symbol that appeals to the mezzo-sexuals.

Absolutely. That doesn’t bother me at all. It seems to be a thing. I suppose seeing somebody being sexual is always going to elicit a response in somebody. Although I don’t quite understand it.

I think part of it is the gender-bending aspect.

Maybe they think you’re really comfortable with your own sexuality. But it also definitely has to do with the music. Let’s not discount this, because people aren’t stupid. If you had me rolling around on a bed with another 45-year-old woman, and there was no soundtrack, trust me, nobody would get aroused. Me in some overly-tight tights and a long shirt rolling around at 7:30 p.m. on a Tuesday? It’s the music. I’m always grateful for the soundtrack to my fumblings.

You recently did an interview with Sir Mark Elder, the conductor of the Hallé Orchestra. There’s a moment when you two are talking about his love of singing. And you’re like, Why would you ever give up being a conductor to sing? I thought I heard a bit of jealousy in your voice. Would you ever want to conduct?

I have thought about it. I said I wish I was a better mathematician, but maybe I don’t need that. I did once do a little bit of conducting in a class at college, and everybody went, “Oh, you’re very good.” I’ve never forgotten it. Don’t get me wrong, I know this is not an easy job, to spend your whole life with your arms in the air, but I would love to not rely on this invisible thing in my throat. I would also love to be able to shape the whole piece. I doubt it’s ever going to happen, but it’s a little fantasy. I would love to have a go, maybe in the dark somewhere in the middle of Iowa, in a town hall where the lights are turned down, who knows?

I’d definitely go to that concert. But in interviews you often talk about the unhappiness and loneliness that comes along with being on the road so much. Has the pandemic made you reevaluate that part of your career?

Yes, completely. This opera is making me wonder what I’ve done with my life and what I’m prepared to carry on doing with my life. I spent the last two years in one place, the same bed. Albeit a bed in my parents’ house. Even though the pandemic has been horrific, for me personally and for the whole world, the one level in which it was absolute gold dust was that I was in one place. I was with my parents when my father died in September 2020…

Sorry for your loss.

…My sister and I couldn’t get nurses in, we couldn’t get anyone from the National Health Service to come. They were dealing with the pandemic. We were determined not to have my parents go into a home, so I ended up doing end-of-life care.

First it was, “Am I going to L.A. to sing under Plácido Domingo?” Then my life stopped. I was in my childhood bedroom looking after my parents for two years. I saw all the seasons. I didn’t have a suitcase open. I was with the people that I love—well, some of them—and it was absolutely marvelous.

I had terrible grief, but I didn’t have this permanent sitting-in-a-room-waiting-for-your-life-to-go-by. I have that again now, being alone until the next rehearsal. It’s just like [“Dialogue des Carmélites”]. What do you believe in? How unhappy are you prepared to be for something you love?

It shouldn’t be like that, but for me it has been. It doesn’t suit me. I don’t think it suits anybody: 30 years on their own in a hotel room? Then again, trying to invest myself in this music and give it out is something I felt I must do.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Have you ever considered just quitting opera?

I hate the lifestyle, but that shows you how much I love the music. Through my 20s, 30s, 40s, as a woman, I didn’t have children. Who says I wouldn’t have wanted children? I think there’s part of me that needs to nest.

It’s a pretty gendered issue: I’ve talked to male conductors who travel constantly, but always say how great their family life is. It seems clear that there’s someone else who’s managing it. I think for women, there’s not the same expectation that there will be a person in the background to manage their family life as there is with men.

I know for sure that it’s no less painful for men to miss milestones or to miss their children; but I also know, speaking to female colleagues, that it’s excruciatingly painful to be away from your children. I couldn’t have done it. If I were a mother, I’d want to do that as well as I possibly could. There just isn’t enough energy in the day to give myself wholly to either thing.

How could you imagine the opera industry being structured so that it would be better for people?

I suspect that it’s going to change anyway after this pandemic. Even young singers have said to me, “I don’t know if I want this life.” Maybe more people will want to just stay home, and it will be structured around people staying at their opera houses. I don’t know if there’s going to be quite the same circulation and air travel. I’m lying in bed at night thinking, “Oh my God, I’ve got to book six flights in the next two weeks to get back and forth to my family. How do I feel about that ethically? Can I justify that?”

How do you do clean opera? I’m sure there’s a way. Maybe there will be better work because of it: Maybe less rushing around might create some deeper, immersive work.

Were there ever moments when you were doing the end-of-life-care for your father where you wished you were back out in the world singing?

No.

Not at all?

I was asked to do Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” in August before he died in September. That’s the piece I’m most invested in; that made me want to become a singer. I wanted to go and do it, but I just couldn’t walk away from my family. It was a difficult decision. We were doing heavy nursing with two people. I suppose I did want to escape at that moment and sing something all-encompassing, even violent in a way.

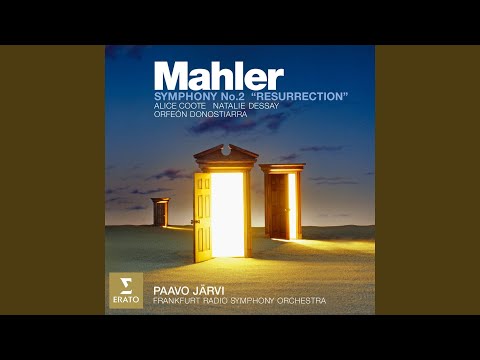

When my father finally died, we weren’t expecting him to die that day. We were in the room and it was pretty horrific. My sister had to go up and look after my mother upstairs: My mother is permanently upstairs, and my father was downstairs. I didn’t want to leave him on his own. I just thought, someone’s got to stay with him. I ended up standing at the end of his bed and singing Mahler Two, the “Urlicht.” I wanted him to hear some music, for him to not be in silence and on his own. It must have been something deep in me. I didn’t think about it. I just started singing. I was crying. I just kept going. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.