In his 2017 film “The Death of Stalin,” Armando Iannucci links the titular event to a letter penned by pianist Maria Yudina: “Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, you have betrayed our nation and destroyed its people. I pray for your end and ask the Lord to forgive you. Tyrant.” In Iannucci’s history-as-farce, the dictator reads this note after receiving a recording of Yudina playing Mozart, and subsequently has the fatal cerebral hemorrhage that would lead to his death on March 5, 1953.

She’s not the first musician many would expect to play a main role in the downfall of the Kremlin Highlander. We know, for instance, of Shostakovich’s denouncement by Stalin as “an enemy of the people,” and his subsequent creative renaissance that took place following the dictator’s demise. We also know the cruel irony of fate that was Prokofiev’s death less than an hour before Stalin’s, which served as one last form of censorship over the composer. In the realm of instrumentalists, we may even think first of Mstislav Rostropovich, whose political activism would come to full force in the final decades of the USSR, but began to show life in 1948 when he dropped out of conservatory in solidarity with the recently-fired Shostakovich.

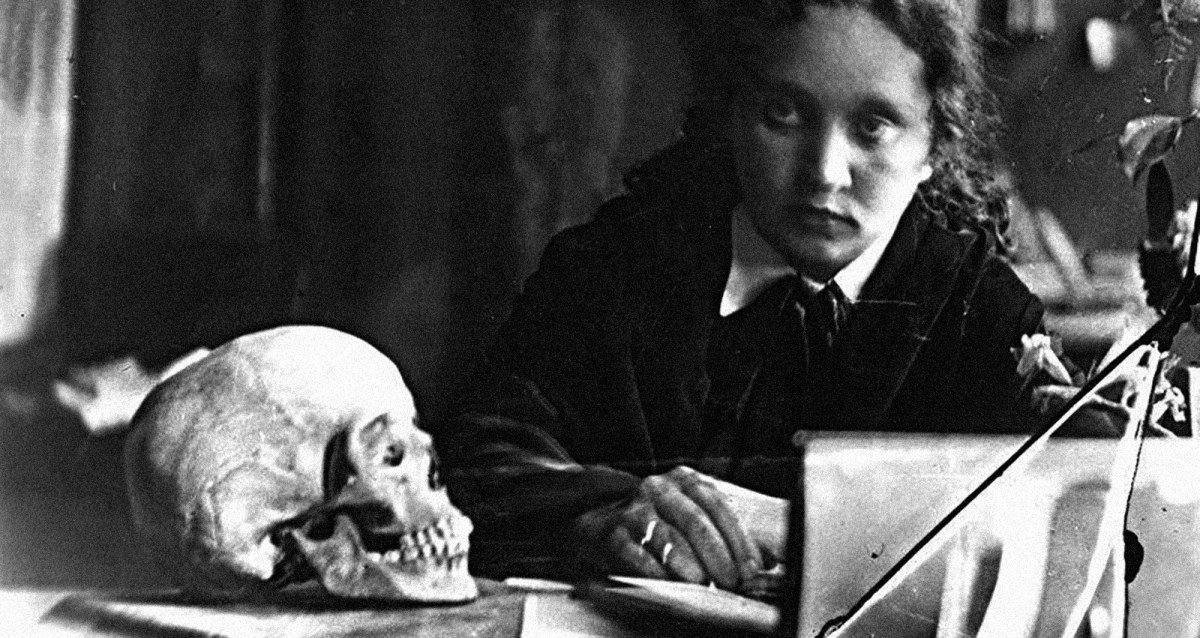

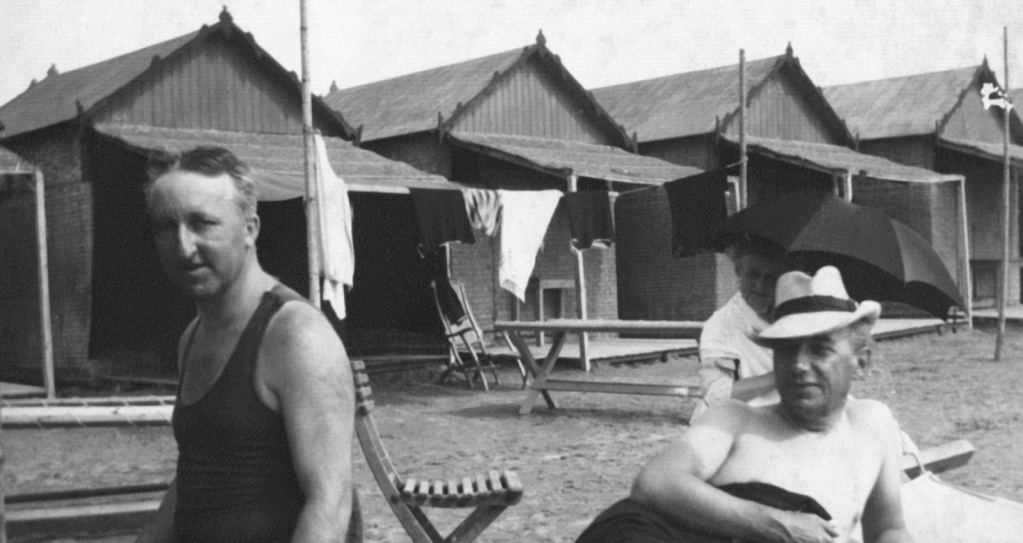

Fewer people know about the pianist who fell foul of the cultural imperatives of socialist realism and refused to play the game to some extent (like Shostakovich) or simply defect (like Rostropovich). Despite this—or perhaps because of it—Iannucci gives Stalin’s fatal blow to a woman who recited forbidden poetry and performed unsanctioned avant-garde piano works in her recitals; a woman who was said to carry around a revolver and who taunted the Soviet leader not only with accusations of tyranny, but also professions of religious belief in a country where God had been declared dead. All of these legends have been appended to Yudina’s biography. Indeed, while many of them are false, she was a notorious and crucial part of Russian musical culture in her lifetime. It’s a cruel twist of history that the 50th anniversary of her death will pass this month with relatively little celebration.

Iannucci didn’t invent the image of Maria Yudina as the pianist who killed Stalin out of whole cloth. Her role in “The Death of Stalin” is a variation of a tale which first appeared in Shostakovich’s memoirs in 1979. In the composer’s telling, the event happened nearly a decade earlier, in 1944, when the dictator heard Yudina perform Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 on the radio and called the State Radio Committee for a copy of the recording. The performance had in fact been a live broadcast, but the Committee officials were understandably terrified at the prospect of saying “No” to Stalin. Instead, they cobbled together a makeshift orchestra in the middle of the night, summoned Yudina to a studio, and recorded and pressed a single copy of the concerto to deliver to the leader’s dacha. Shostakovich recalls that Stalin rewarded Yudina with 20,000 roubles for the recording, but that Yudina repudiated this. She donated the money to the church she attended, and replied to Stalin: “I will pray for you day and night and ask the Lord to forgive your great sins before the people and the country.” It was, in Shostakovich’s words, a “suicidal” letter.

Given that the authenticity of Shostakovich’s memoirs is widely doubted and that this story is otherwise unsubstantiated, it is safe to assume that the entire ludicrous episode is fabricated. The same goes for the revolver, a claim courtesy of Richter, whose relationship with Yudina was frosty to say the least. Another popular legend about Yudina is that she won the much-coveted Stalin Prize for her musicianship. As musicologist Marina Frolova-Walker has shown, this is also false, which comes as no surprise given how out-of-favor Yudina was with the Soviet regime.

What, then, is true? For one thing, the legends of Yudina’s concerts are: At their most outrageous, the pianist, often clad in black, voluminous, nun-like dresses, would recite the forbidden poetry of Boris Pasternak in between performances of the kind of avant-garde, atonal music that was (by design) extraordinarily rare in the Soviet Union. She idolized Stravinsky, whom she considered a colossus of contemporary music. She passionately advocated for her one-time classmate, Shostakovich, and the lesser-known Andrei Volkonsky. Her insatiable appetite for contemporary music meant that she regularly sought out new compositions from budding composers, often with little subtlety. In October 1961, she wrote to a young composer, imploring him to write a piano concerto for her, while openly admitting in the same letter that she had never heard or seen a note of his music and could not remember his patronym. The 26-year–old Arvo Pärt never replied.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

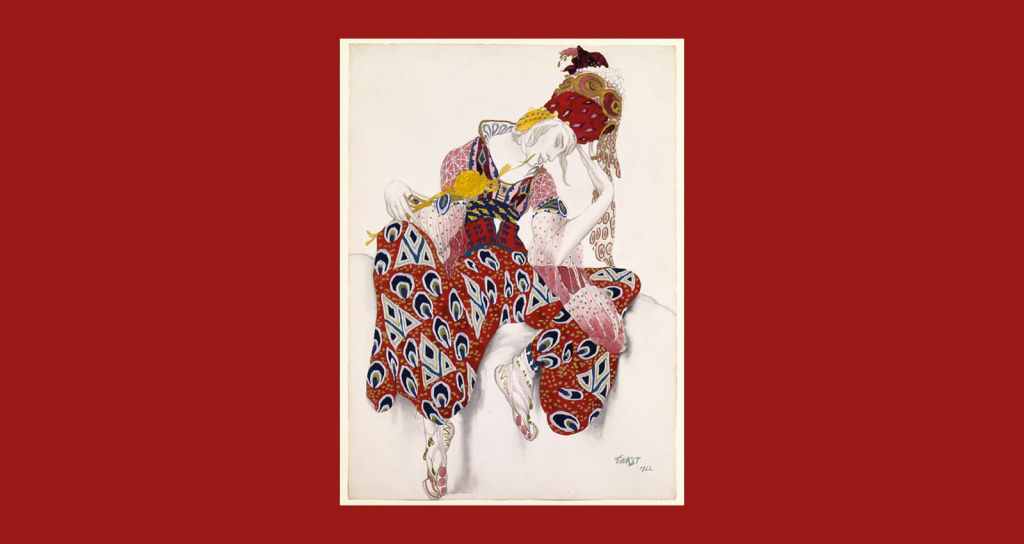

Yudina, for whom “even the greatest of old music is…nothing more than a museum,” championed what was going on in the rest of Europe, including the music of the Second Viennese School and others like Paul Hindemith, Ernst Krenek, Pierre Boulez, Olivier Messiaen, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Iannis Xenakis. But she wasn’t merely focused on maintaining her place at the frontlines of 20th-century composition. Yudina also looked to developments in literature and philosophy: She corresponded with Theodor Adorno, for instance, and her aesthetic thinking was marked by her close relationships with the likes of Pasternak and philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin. If the Shostakovich-credited anecdote of Yudina’s response to Stalin was fantastical, there was at least an element of truth there as well, as Yudina openly professed her religious beliefs in an aggressively atheistic state (though she was born Jewish, she converted to Russian Orthodoxy at a young age).

This is a snapshot of Yudina’s path of nonconformity, one marked by a powerful, relentless individualism. This description could equally be applied to her playing. Critics have rarely known what to make of her recordings, which capture a performing style of shocking spontaneity and force. She went to great extremes in her live performances of romantic music, adopting drastically flexible tempos and apocalyptic dynamics to the extent that Richter quipped that the music was “no longer [by] Schubert or Chopin, but Yudina.” If you seek composer fidelity in its modernist, Urtext formulation, Yudina is not for you.

Immortalized in these recordings, however, is a remarkable musical spirit that seems, in its brazen rejection of convention, to pursue a deeply philosophical experience; one that does not simply exploit novelty for the sake of novelty. She sought the transcendent everywhere, her most revealing musical reflections often idealizing that which she felt freed her from everyday, earthly experience.

Such flagrant civil disobedience and firmly-held artistic and religious ideals came at great personal cost. While Stalin’s death led to the comparatively less restrictive era of Nikita Khrushchev, Yudina continued to endear herself to no one in Soviet officialdom. In 1960, she lost her prominent academic position at Moscow’s Gnessin State Musical College. In December of that year, she wrote to Volkonsky: “I’ve been let go from the Gnessin Institute precisely due to new music and, probably, [her readings of] Pasternak.” It wasn’t the first time that she was dismissed from a senior academic post. She was fired from the Petrograd Conservatory in present-day St. Petersburg in 1930, and she suffered the same fate at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Conservatory in 1951. The more scandalous her recitals became, the more she was subjected to official concertizing bans, particularly in the last decade of her life. She was effectively barred from ever leaving the Soviet Union, managing to travel abroad only twice, and then only to member states of the Eastern Bloc: East Germany in 1950 and Poland four years later.

Stranger than fiction

Yudina’s musical principles meant that she was ostracized from official—and, crucially, materially supportive—cultural circles. “I’m not a member of the Union of Soviet Composers,” she wrote in February 1962, “and I no longer wish to be, so that I can maintain my independence; on the other hand, this means that I receive no help, and that my living conditions have become extremely difficult since I was let go by the Gnessin Institute.”

It’s easy to romanticize a struggle like this one. Yudina herself was possibly guilty of it, an understandable defense mechanism in the face of exclusion. But there is a sadness to her late years, one which was especially evident in the repatriation of Stravinsky for a celebration of his 80th birthday in the autumn of 1962. Though instrumental in laying the groundwork for this defining musical moment in Soviet history, Yudina did not get to meet her idol in any meaningful way. When the festivities began, Stravinsky overlooked her in favor of both official Soviet representatives and the more valued male composers of the time. Yudina wrote Stravinsky was constantly “surrounded by a multi-person entourage the barbed wire of which was impossible to penetrate.” As an unreliable renegade, Yudina was not included in Stravinsky’s circle and she fell through the cracks of his visit. “So, [Stravinsky] ‘exchanged’ me with those who are at the helm … and I am no longer needed and, ergo, can be disregarded,” wrote a distraught Yudina in the aftermath of the composer’s visit.

Stravinsky’s return epitomizes Yudina’s tragedy: She who had done so much to give life to new music (and suffered for it) was conveniently cast aside when it was politically expedient to do so. Other composers more thoughtfully recognized Yudina for her commitment to new music. She suffered from recurring illnesses in her later years, and when she died on November 19, 1970, Karlheinz Stockhausen bitterly decried that “a society which not only shows itself incapable of recognizing [those] endowed with extraordinary psychic faculties, but which isolates them, is not able to adapt to progress.… [The] future will show us that personalities like Maria Yudina are artists in the most fundamental sense of the term.”

That future has not yet come to bear. While many of Yudina’s contemporaries, like Richter and violinist David Oistrakh, continue to be heard on reissues and anniversary box-sets from some of the most prestigious classical record labels, Yudina’s recordings have typically flown under-the-radar as expensive box sets on labels like the former Soviet producer Melodiya (which is now distributed through the Canadian classical label Analekta) and reissue factory Scribendum.

An enormous part of 20th-century music in Russia, Yudina has since largely been forgotten, much more so than the many other, exclusively male contemporaneous musicians whose music she promoted. Hers was a musical voice whose convictions and aesthetic provocations came into conflict with the power of Soviet normativity, and as neither a domestic exemplar of Soviet music or a successful defector, much of her story has been confined to the margins and footnotes of music history. Undoubtedly, there are many other formidable and brave musical individuals whose narratives remain untold. Perhaps few are quite as mystifying. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.