Pity Paul Dukas. For most listeners—even serious music lovers—his work is the mere soundtrack to the anthropomorphic avatars of the Disney corporation. Despite floating in the same fragrant creative broth of early 20th-century Paris as Igor Stravinsky and Claude Debussy he has been rather overshadowed by both, to say nothing of his twelve-tone contemporaries in Vienna. Dukas’ harmonies, orchestration, and adventurous gender politics were radical for his time, but his fairy-tale opera “Ariane et Barbe-bleu,” for instance, plays second fiddle to that other collaboration with Maeterlinck, Debussy’s “Pelleas et Melisande.” His audacious 1912 Poème dansé “La Péri” has been eclipsed by other Diaghilev ballets: Stravinsky’s “Firebird” and “Petrushka.”

Laura Watson’s new study—the first in English—puts Dukas center stage. She paints a picture of an imaginative and reflective composer and essayist, whose elusive modernism and acute artistic responses to the questions of his time are surprisingly adventurous. Dukas was intensely self-critical and left behind a number of unfinished works; the artist was unsettled and tentative, lacking the bravado of contemporaries whose music burns rather than smolders. But Watson emphasizes that Dukas’ scant oeuvre does not reflect creative failure. Her subtitle, Composer and Critic, is clear in its message that Dukas’ creative life encompassed writing as much as it did composition.

Born in 1865, Dukas studied for nearly a decade at the Paris Conservatoire from 1880, finding himself at odds with the prevailing institutional ethos and suffering a number of bruising rejections, particularly in the prestigious Prix de Rome competition. He developed his interest in music criticism, which he wrote throughout his career, early on at the Conservatoire. Later on, as a teacher, Dukas inspired many of the most idiosyncratic musical modernists, such as the Mexican Manuel Ponce and Maurice Durufle, whose music sits uneasily between innovation and tradition. Indeed Olivier Messiaen was probably Dukas’ most famous pupil, and the piece Messiaen wrote for Dukas on his death in 1935, a three-minute work for piano characterized by non-functional harmony and distended phrasing, retrospectively spotlights Dukas’ creative audaciousness.

Dukas was disdainful of convention. He was a militant explorer, particularly when it came to representing gender and sexuality in his works for the stage. There’s no doubt that his own ambiguous position as a French Jew living in the shadow of the Dreyfus affair intensified his fascination with figures who try to resist the strictures of the powerful; the women of his work shout, in their own way, Zola’s J’accuse! This put him at odds with the nationalist mood of French musical culture in the last decades of the 19th century, his teachers particularly disdaining his commitment to Wagner’s radicalism.

Dukas’ life and work often made common cause with women who opened up the cracks in the patriarchal worlds of opera and drama, both onstage and off. Dukas was writing at the moment of the nouvelle femme and the suffragettes. He responded in a distinct way to the extreme and compromised presentations of feminine sexuality we see in Richard Strauss’ 1905 “Salome,” a skin-crawling tale of desire and violence, as well as of course Debussy’s “Pelleas et Melisande.” Dukas’ 1906 take on the Bluebeard fairytale, “Ariane et Barbe-bleu,” picks up the threads of both Strauss and Debussy—not least in collaborating with Maeterlinck for the text—but pulls on them much harder. As Watson notes, the opera “rattled many male commentators” and found an admiring audience in the educated class of femmes nouvelles.

“Ariane” breaks with the fatalism of Strauss and Debussy—the transgressively desiring leads in their operas are either metaphorically or literally crushed—by empowering the title character. Ariane tries to liberate Bluebeard’s other wives, and, although she fails at that, she liberates herself nonetheless, leaving Bluebeard’s mansion with her nurse for the outside world. Her defiant response to Bluebeard’s accusation of betrayal (“You too?”) is “moi surtout”—me, above all—singing music of sublime authority and assurance. By contrast, in Bartók’s 1918 version of the same story, Bluebeard’s wife Judith is smothered and pinned by the jewels he adorns her with, and his other wives are silent throughout.

Ariane’s story sees her reject the mob of villagers outside and relentlessly challenge Bluebeard himself, often, as Watson’s account of the score shows, coming on top in musical terms too: in her great “Diamond Aria,” where she describes the treasures behind Bluebeard’s forbidden doors, Ariane’s music blends a heightened and highly articulate expressive vocal style with soaring, symphonic lyricism. For Watson, this endows Ariane with greater communicative abilities than her husband, who is limited to “monosyllabic grunts and glowering.”

The work was received as a radical social commentary on the place of women in society. “The opera portrayed,” Watson writes, “how the erosion of restrictive gender roles went hand in hand with a society beginning to acknowledge a range of female subjectivities, including women’s autonomy in their private lives, same-sex desire and increased access to the public sphere.” Ariane renouncing the roles of wife and mother had special urgency in a France anxious about depopulation, where its masculinity was “under siege.” That anxiety is reflected in the opera’s meandering whole-tone harmonies, which unsettle the audience’s sense of place and order.

“Ariane” was also the vehicle for a distinctive performer, the mezzo-soprano and partner of Maeterlinck, Georgette Leblanc. Leblanc was an innovative vocalist, renowned for her realist expressionism and the lucid, theatrical diction she brought to performances. Dukas’ vocal writing in “Ariane,” with its declamatory and vivid approach to combining text and music, presages the half-spoken half-sung Sprechgesang that would come to be so closely associated with the avant-garde of Schoenberg and Berg. No doubt Leblanc’s association with the work bevelled its political edges because of her status as a fiercely public feminist who demanded in interviews to be taken seriously.

The role itself reflects Dukas’ transgressive sensibility. The mezzo-soprano, Watson notes, is the most “non-conformist of female voice types”; Catherine Clement suggests the mezzo “poses resistance to each and every order.” It’s a voice not only blessed with dissident heroines like Carmen or Rosina, but also one that can clamber all over the traditional female tessitura casting calls, playing boys and girls, tragic and comic alike. The “Diamond Aria” in “Ariana” expresses precisely this character’s dazzling force and presence, radiant and beguilingly sensuous in equal part.

This was not Dukas’ only insurgent exploration of gender and sexuality on stage. In “La Péri” (1912), the protagonist, Iskender, flounders in his attempts to conquer the mysterious spirit of the title. He is eventually overpowered by La Péri’s dance, and she returns to her paradise whole and undiminished by the encounter.

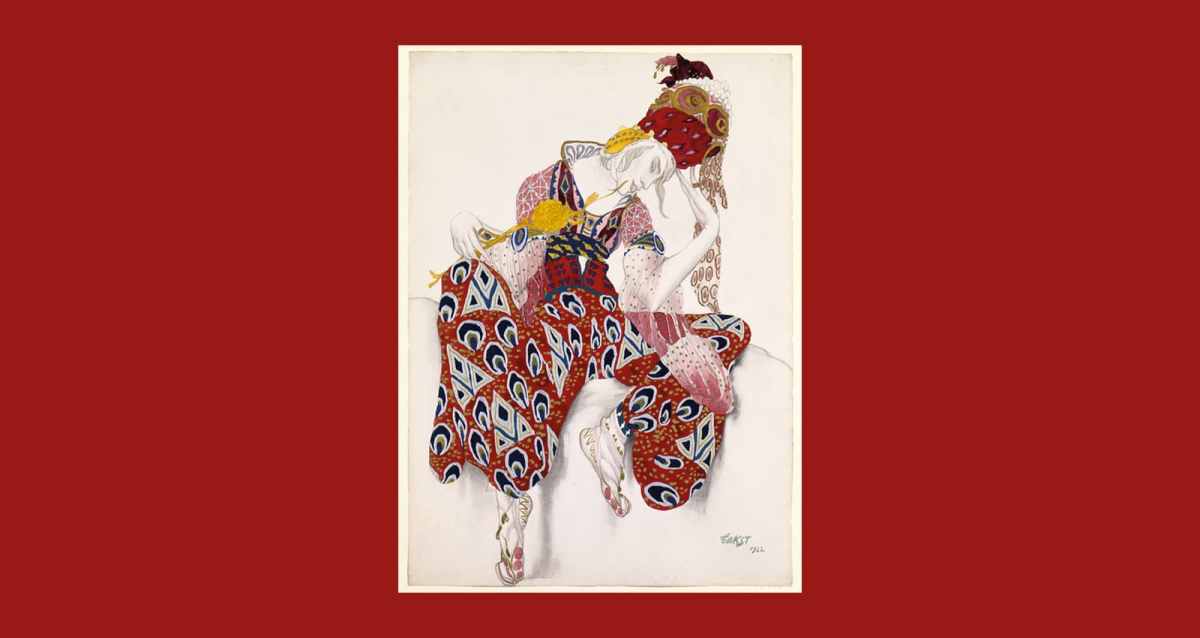

Dukas presented this work at the behest of Diaghilev and his Ballet Russes, capitalizing on the orientalist successes of Stravinsky’s “Firebird” and “Petrushka.” “La Péri” is an exotic and mysterious journey through ancient Persia, full of magicians and sprites. The story of its performance is a fitting tale of female empowerment. Diaghilev felt that Nijinsky’s counterpart, the ballerina Natalia Trouhanova, was insufficient to the demands of the role. Dukas split with Diaghilev, choosing to premiere the work instead with Trouhanova’s own company. Well-known to the public after she danced the scandalous Seven Veils sequence at the premiere of “Salome” in Paris, Trouhanova was also, as Watson notes, a serious contender challenging Diaghilev’s dominance of the Paris ballet scene. She organized concerts in direct competition to his, was fiercely entrepreneurial, and mesmerizingly unconventional onstage.

In his essay-writing and approach to composition, Dukas reveals a fascination with Beethoven’s late style, from which sprang an intense interest in variation as the guiding principle of his music. For Dukas, variation represented a more extravagant and liberal way of imagining musical development, freed from the stringent and rather more masculine straitjacket of traditional sonata form, with its expositions and recapitulations; Susan McClary’s stringent reading of musical form saw the sonata’s tensile energy as patriarchal. Dukas’ small 1909 piano work “Prélude élégiaque sur le nom de Haydn” is full of remote harmonies and peculiar modulations, ditching most diatonic convention; his Rameau variations of some 10 years earlier prove similarly dreamy and expansive.

The tessellated sequence of arias about Bluebeard’s treasures in “Ariadne” also became a set of variations. This preponderance of variation in Dukas’ music—the gateway, Watson suggests, to fantasy and freedom—expresses a fascination with the undetermined, the “non-teleological” in Watson’s words, that comes from his interest in 19th-century Russian music. This music of expansion and imagination, which prefers to change rather than recapitulate or return (as is the convention in sonata form) expresses Dukas’ dissenting willfulness and echoes his cultural politics, both as a French Jew and supporter of radical women.

Dukas gave over pages and pages of his articles in La Revue Hebdomadaire to the question of musical meaning, often puzzling over the relationship between music and text, librettist and composer and dramatist, or what it means to speak of illustrative “program” music and tone painting, à la Berlioz and Strauss. In this respect he strove to produce a distinctive response to Wagner and his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk in music for the stage. It was Wagner’s ghost which Dukas tried to exorcise in “Ariane” and in voluminous essays on the German artist, such as 1892’s reflections on “Das Rheingold.”

Dukas’ career is full of episodes instigating contact and overlap between artistic forms. His most famous work, of course, is a symphonic poem, presented in a brilliant fusion of media in “Fantasia” (1940). For Watson this intermingling of film, color, design, and music, with its anthropomorphic and musical imagination, presages Martin Esslin’s idea of the theater of the absurd. “L’Apprenti sorcier” “anticipates Absurdist aesthetic conditions”—after all, the main protagonist is a broom—and this orchestral scherzo hovers at the limits of a new “dramatic music” Dukas imagined as “unperformable.” In what sense? Dukas’ music is gesture, impression, and pure action—in keeping with the theatrical principles of Ionesco and Esslin—and not wedded to vocal expression or traditional musical storytelling.

Alongside the fact that Dukas wrote his major works for the stage, that most interdisciplinary space of artistic creation—he even sketched a stage design for an unfinished opera after “The Tempest”—the composer was always fascinated with crossing boundaries of form and medium. Elsewhere Watson describes the Rameau variations for piano as “prismatic,” as if it might be a cubist collage; Dukas naming “La Péri” a Poème dansé rather than a ballet also speaks to this interdisciplinary spirit, his experimental and modernist impulses. For the philosopher Jacques Rancière modernism described a boundary-crossing endeavor from artists in all media that means blending them with each other.

Dukas crossed geographical borders as well as formal ones. The breadth of his imagination is reflected in the cosmopolitanism of his music and criticism. He was more than open-minded in an essay reflecting on an “Oriental Operetta” he saw in Paris, proposing that musical values are only relative. Watson connects his desire to write music that would cross national borders to his Jewishness, a quality manifested in a late style of his own that is exilic and searching, with a sense of placelessness. As a composer disconnected from both musical past and avant-garde future, possessed of a willingness to question, he is a potent model for our time. Dukas’ music is more sinuous and understated than that of his more famous contemporaries, but is unique in its exploration of gender and cultural difference, issues that have begun to resonate strongly with today’s classical music audiences. Taken alongside his adventurous and thoughtful essays, Dukas’ music represents a wily and reflective episode in musical history. ¶

Comments are closed.