Some babies are put in swaddling clothes. Others are born into families where expectations are so great that they begin to resemble similarly physical restrains. Siegfried Wagner, the only son of Richard, was born in 1869. Richard wrote the “Siegfried-Idyll” to mark the occasion, a work with and flashes of mesmerizing genius. As the male heir to Wagner and the Bayreuth clan, Siegfried was also required to compose. But when his works inevitably failed to measure up to his father’s, his wife posthumously collected them and prohibited their performance.

“My list of beloved unknown greats is very long. Siegfried Wagner is not on it,” said Kevin Clarke, one of three curators of an upcoming exhibition at the Schwules Museum (Gay Museum) in Berlin, on a recent evening. Indeed, Siegfried’s music has a strange blockiness to it, an element of pastiche: his slow passages lack the unpredictability of his father or the agonized beauty of Richard Strauss, and his playful woodwind writing is Mahlerian without the melancholy. Siegfried’s life was more interesting than his music, and so that is what the Schwules Museum will focus on when the display opens on February 17.

And what a life it was. Siegfried was a composer, a conductor, a manager at Bayreuth, an ambivalent Nazi and an enthusiastic gay man. For the curators, the question then became: What aspects of his life are important? In particular, whether his problematic politics were worth exploring in detail became a topic of contention. “I find it astonishing that a lot of heterosexuals think that they can reduce gays to just the sex part, and leave out everything else,” Clarke told me. “They think, ‘Oh, we’re doing an exhibition about the gay side of Siegfried Wagner, and let’s just focus on the sex. Let’s leave all the Nazi [stuff] out.”

Music wasn’t Siegfried’s first instinct. Instead, he wanted to be an architect. He was a timid kid, though, and bowing to family pressure, he took composition with Engelbert Humperdinck. (One catalogue essay for the exhibition, which I agreed not to quote directly as it is not yet published, connects Siegfried’s homosexuality and tame music to his overbearing mother, shyness, and supposed lack of virility—an offensive take I believe could only exist, in 2016, in the dustier corners of German musicology.) He studied in Frankfurt, where he met a young British composition student named Clement Harris and fell in love. In 1892, they undertook a trip to Asia together as the only two passengers on a cargo boat belonging to Harris’s family. The trip was clearly a high point in Siegfried’s life: he drew and composed, and described living with Harris like “two Adams.”

Siegfried Wagner, “Sehnsucht”; Werner Andreas Albert (Conductor), Hamburg State Philharmonic Orchestra. “When I first listened to ‘Sehnsucht’ I thought, ‘OK, I’m going to hear the homoeroticism somewhere in there.’ No, I did not!” said Clarke.

He also finally accepted that he would have a career as a musician during this this trip. He was inspired, he wrote, after hearing a performance of the Bach Chorale “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunder” in Hong Kong. In 1893, he conducted his first concert, including works of his father. Clement Harris was killed in 1897, at the age of 25, in the Greco-Turkish War. Siegfried dedicated a 1923 symphonic work, “Glück” (“Happiness”) to Harris, and kept a photograph of him on his composition desk until his death.

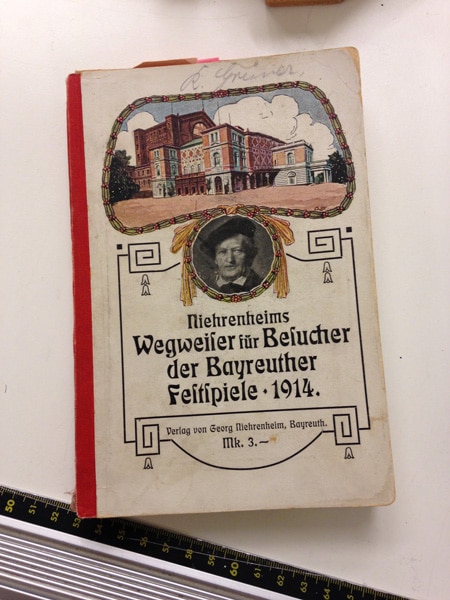

Siegfried continued to visit Berlin, where he had studied after Frankfurt and which had become the world’s first gay mecca, regularly for sex. For this, he was blackmailed, and his family paid hush money to keep his affairs covered up. After an initial period of learning from his mother Cosima, he became director of the Bayreuth Festival in 1906, after she had had a stroke. His first tenure at the festival lasted until 1914, when World War I broke out and the performances were canceled. At the same time, the journalist Maximillian Harden—whose digging had led to the Eulenberg affair—began to pursue a story about Siegfried’s love life. So he married a girl named Winifred within the month.

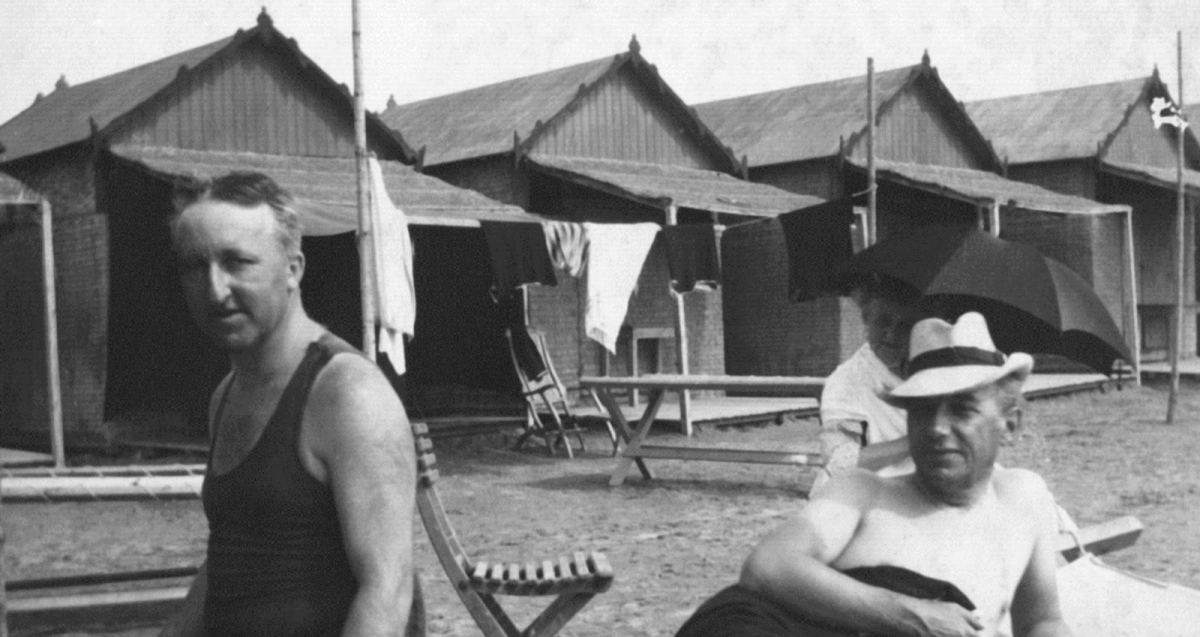

At the time of their wedding Winifred was an “androgynous 17-year-old,” and Siegfried was 45. Still, the marriage took the heat off him. After World War I, he began to focus on getting the Bayreuth Festival up and running again. His family had lost its entire fortune to the hyperinflation in Germany, though—the Wagners were broke. Around this time, and like his wife and relatives, including his brother-in-law, “racial theorist” Houston Stuart Chamberlain, Wagner became a supporter of Hitler and the National Socialists. One reporter from the time referred to him as a “warm friend” of Hitler’s—a phrase just a shade away from the German warmer Bruder, a euphemism for gay from which the contemporary term schwul is derived.

Siegfried’s relationship with the Nazis was more complicated than his wife’s. He was a supporter: in a letter from 1923, he wrote, “My wife fights for Hitler like a lion! Magnificent!” He also didn’t fit in: Goebbels called him “feminine” and “rather decadent.” Siegfried went on a Bayreuth fundraising tour to the U.S. in 1923-24, where his reputation as a Nazi proceeded him and he had only limited success. (He met Henry Ford.) In response, he moderated official Festival attitudes towards Jews, claiming that everyone was welcome and asking that guests there refrain from talking politics. In 1924, Jewish visitors to the Festival were spat on—Siegfried, timid and tied up in the family legacy, asked the Nazis not to do so, but that was the limit to his action.

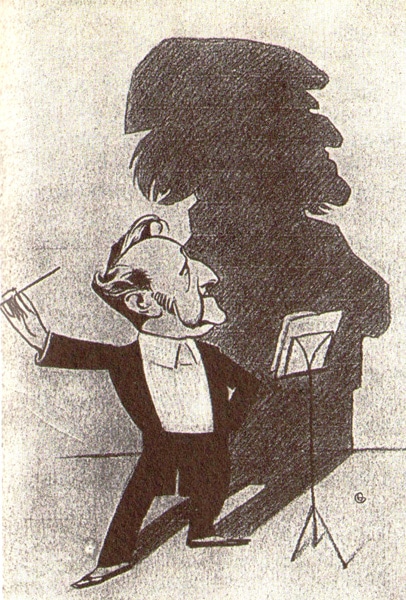

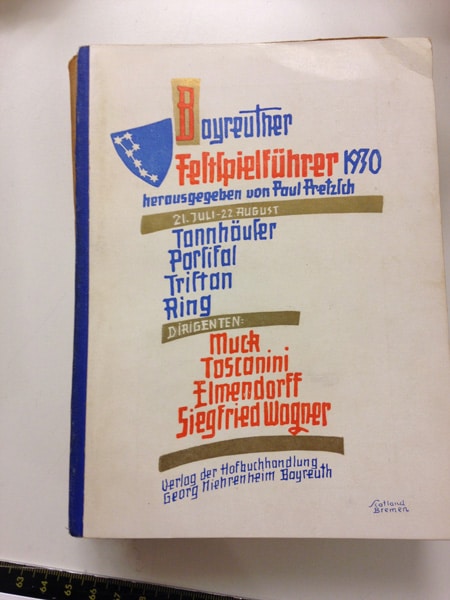

Siegfried’s second tenure as Bayreuth festival director was quite successful. Nevertheless, for the rest of his life, he was caught up in political and “racial” debates. He invited a Jewish Wotan named Friedrich Schorr to Bayreuth, which made Hitler decline his invitation in turn. Other performers were rumored to be lesbian or gay, such as the tenor Max Lorenz; at one point after Siegfried’s death, Winifred intervened with Hitler personally to get charges of homosexuality against Lorenz dropped. Siegfried also brought in Arturo Toscanini in 1930, the first non-German conductor ever to take the podium at the festival. This was the first year that the Bayreuth Festival made a decent profit. The same August, Siegfried passed away. His works, functional as inoffensive and non-“degenerate” pieces, continued to be played until 1945, when Winifred imposed her moratorium on them. (The exact reason for this is unknown. Some performances did take place under threat of legal action by the Wagner family; after the copyright expired in 2001, concerts have become somewhat more widespread.) Siegfried’s private correspondence now remains in a locked safe in the possession of a granddaughter, herself now in her 70s. No one knows what’s in there.

Siegfried’s struggles as a gay man and his Nazi political views can’t be neatly separated from one another, and they mean that his relationship to posterity is ambiguous—one part deeply sympathetic, another viscerally abhorrent. Interestingly, the scholarship doesn’t necessarily reflect this highly murky picture. One book, by his first biographer Peter Pachl, focuses on the music and details of his life, but avoids politics. Another, by Brigitte Hamann, is a history of the Wagner family that delves into its racism, anti-Semitism, and relationship with Hitler.

The debate among the curators of the Siegfried Wagner exhibition is a version of an evergreen conversation in the music world, in microcosm. Do a musician’s political views matter? Jakob Ullmann, a composer who was targeted by the East German Stasi, told me in an interview in June, “Every musician has a responsibility to make sure his music can’t become an instrument of propaganda.” If that is the aesthetic test, Siegfried failed it badly. Because he avoided integrating 12-tone music or jazz, as Clarke told me, 1920s right-wing nationalist groups “performed Siegfried operas as a statement. You can’t blame Siegfried for that happening, but he basically profited from it.”

For white gay men like myself, it’s another reminder that gayness and a cosmopolitan environment don’t necessarily inoculate against repugnant ideologies. (See: Thiel, Peter and Yiannopoulos, Milos.) The same is true of artistic creation: the act itself often isn’t enough; the result matters. If it’s weak, and the time is dangerous, art can easily be swept up in a flood of propaganda. Siegfried Wagner was born in a tight spot. Let’s remember that, despite the fascinating flourishes of his personality, he never quite got out of it. ¶