In 1905, two years after his Met debut and two minutes into an interview with the New York Times, Enrico Caruso came tantalizingly, presciently close to coining the term “fake news.” Over oysters and martinis, the first question launched, the Neapolitan tenor looked at his interviewer incredulously:

“Dolls? Dolls? Ma che? What dolls do you mean?” he asked.

“Why, those dolls they say you keep upon your table for luck,” replied the journalist.

“Bah. Dolls. There are no dolls. I have no dolls. They are what you call a—a newspaper—a what you call—”

“A fake?”

“Exactly. Thank you. Fake.”

There’s just an inch or so separating the words “newspaper” and “fake” from being a clear beacon of presentiment. But all the reality of the moment is in that inch.

Caruso was a singer who lived just on the edge of that inch. He combined the centuries-old tradition of mythologizing the onstage and offstage lives of opera singers with the increasing pace of mass communications in the 20th century. “For Caruso, as for other celebrity recording artists,” writes David Suisman in Selling Sounds, “his work as a performer did not cease to matter but was subsumed into something more complex, his celebrity.”

Eventually, Caruso would work with Edward L. Bernays, the founder of modern public relations (and Sigmund Freud’s nephew), who wrote in 1928: “This is an age of mass production. In the mass production of materials a broad technique has been developed and applied to their distribution. In this age, too, there must be a technique for the mass distribution of ideas.”

Caruso was in the right place at the right time for mass distribution: He became the face of RCA Victor as just as victrola records became widespread. His popularity increased around the world through over 260 records made in his lifetime. An early ad called the recordings “one of the most natural and faithful portraits of Caruso yet taken.” Another ad that ran after the tenor’s death: “You hear the real Caruso.”

But what is real is shaped by our own perceptions, perceptions that are in turn malleable and easily influenced. In the case of Caruso, we can see how the invisible hand of publicity continues to map and remap the disputed borderlines that allow us to find that inch of truth. It’s a covert act of cartography that continues today.

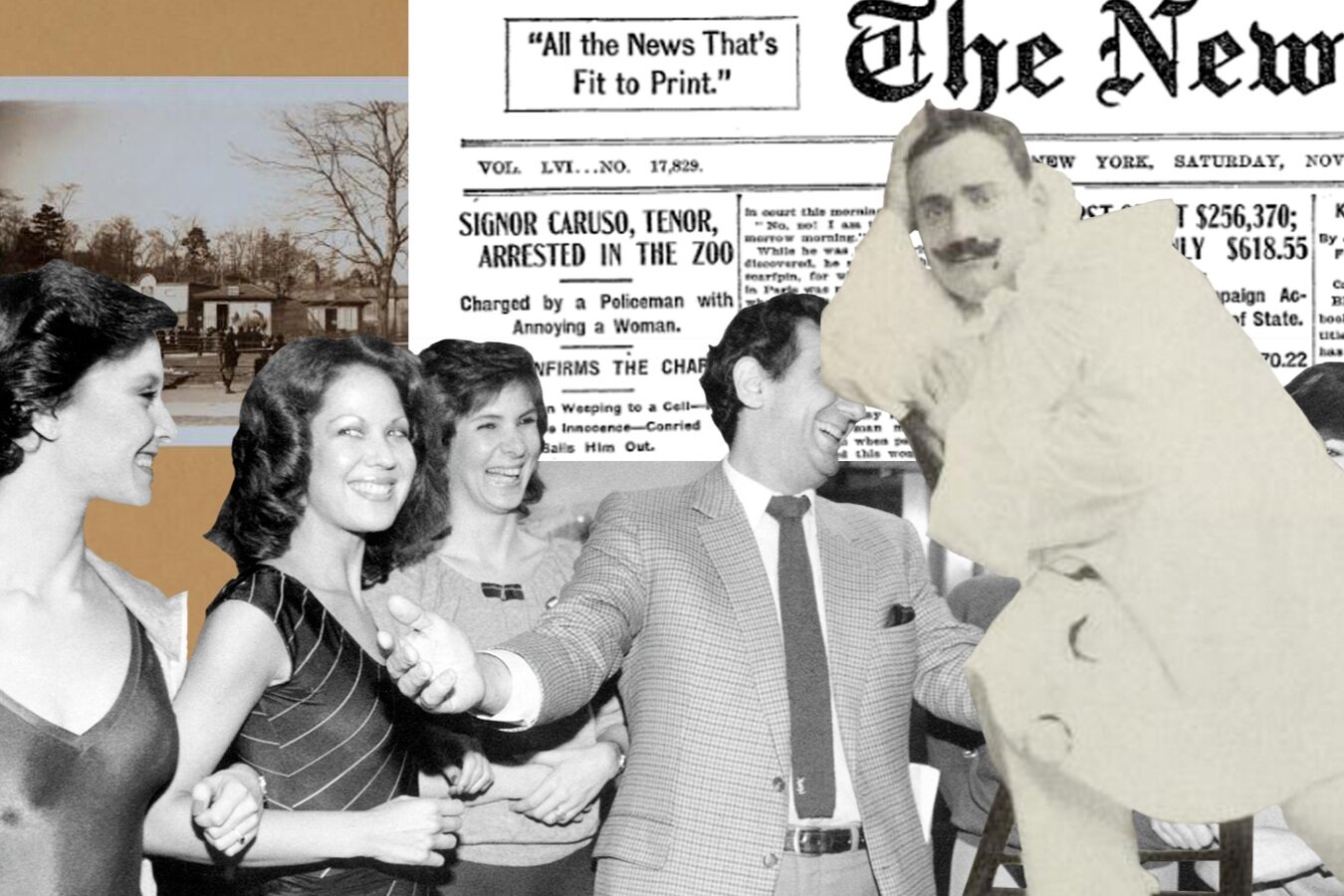

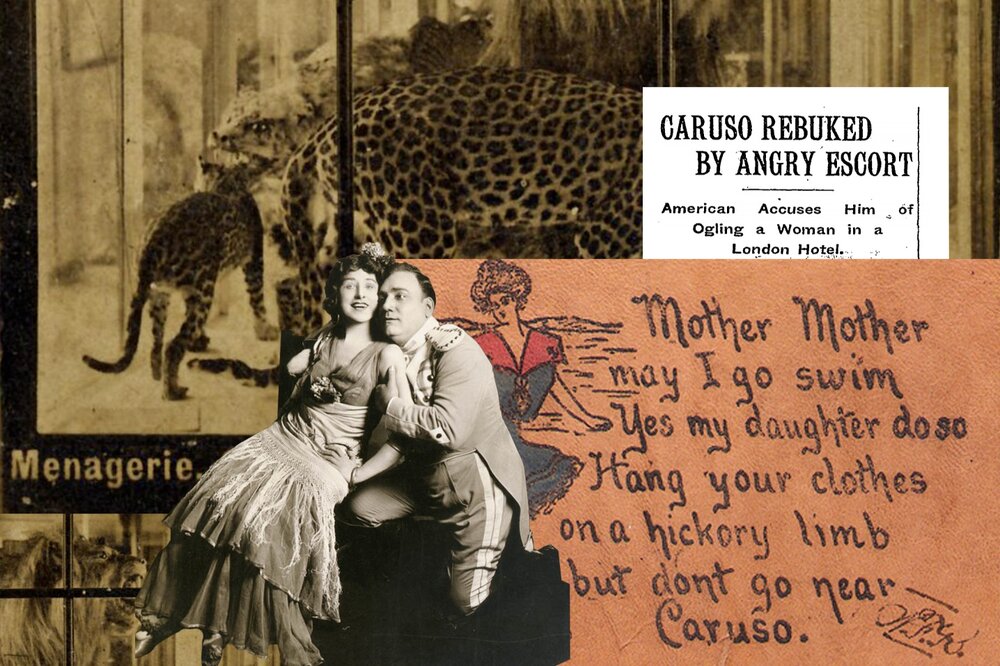

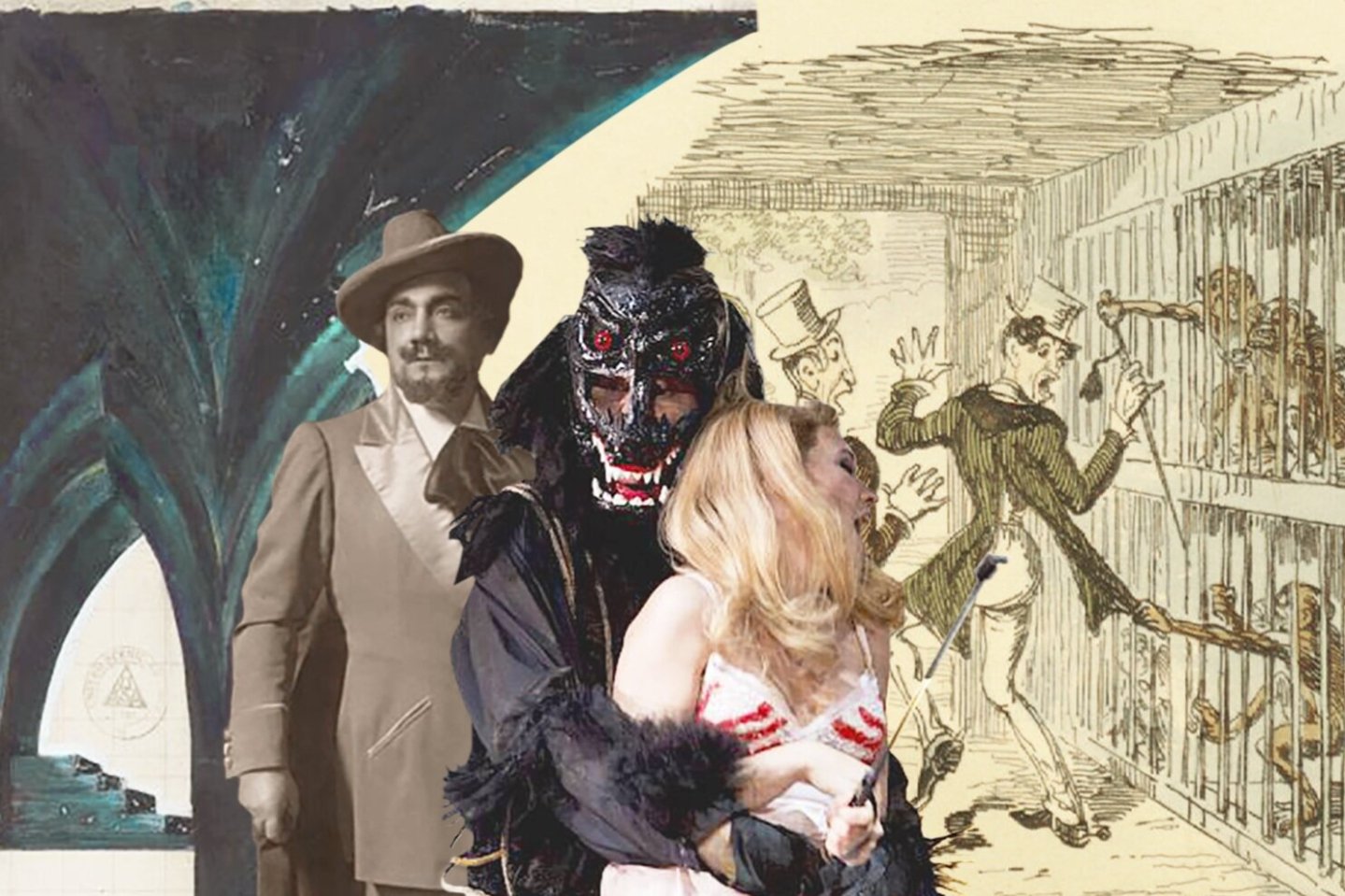

One year after his oyster-and-martini–fueled interview, Caruso would once again make New York Times headlines. On November 17, 1906, the paperran a front-page story: “Signor Caruso, Tenor, Arrested in the Zoo.” Caruso had been detained the day before for “annoying a woman who stood near him” in the Central Park Zoo’s monkey house. James Caine (sometimes referred to as James Kane), who was considered an “expert” in the task with a faultless record, made the collar. He had spent over a decade patrolling the monkey house, which was, in New York and beyond, a polestar for misconduct. Moralists believed that the unpredictable patterns of primate masturbation in public could lead to spectators abandoning decorum. Many men would turn this into an opportunity for debauchery, even blaming the odd grope on a far-reaching monkey.

As Caine told the story to the Times, he had seen Caruso harass several women that day over the course of roughly 45 minutes. Caine initially approached two teenage girls whom he’d seen Caruso grope, but they refused to file a claim out of concern for their “reputations.” When he saw Caruso repeat the pattern with a middle-aged woman, he insisted on an arrest. The woman had also objected to appearing as a complainant “as she was a married woman and her name might be dragged into the newspapers.”

Caine told her “it was her duty to punish any man who annoyed women,” and so she gave the name Hannah Graham and an address at 1756 Bathgate Avenue in the Bronx. Both pieces of information were printed in the Times report, which led to “squads” of journalists searching the Bronx for the mystery woman.

While “annoying” women seems like a small offense to warrant the response that followed, it was considered a criminal act in 1906, referred to then as “mashing” (likely a reshaping of the French catcall “ma chère”). The city of Omaha went so far as to have a “mashing schedule” with different fines applied to increasingly-offensive terms (calling a woman “chicken” would cost a man $5; “baby doll” was $20). Toledo had a standard charge of $50 for molesting or insulting any female; in Houston it was $100 for any man “who shall stare at, or make what is commonly called goo-goo eyes” at women. A 1909 letter to the Times by a young woman who had moved to New York from New Orleans asked why she “should be grossly insulted at least a dozen times a day by that despicable creature, the New York masher.”

Caruso’s side of the story, however, maps a different reality: On his way to meet a friend, he decided to walk through the park, up the East Drive. Soon, he saw some deer. “They were very attractive.” Then he passed by the lions and elephants. “Then I saw the monkeys and enjoyed them very much.” When a woman “about 40 years old—a German, I think she was” followed him, he walked away. He noticed that she was continuing to follow him, so he left the monkey house. That’s when a policeman grabbed him.

“The woman’s charge was impossible,” Caruso later told the Times. In his testimony the following week, he would allege that he had been the victim of harassment by the woman, who had looked at him “in such a way that I took her for a doubtful character.”

“Did it embarrass you?” asked his defense attorney.

“It did a little,” Caruso responded.

Caruso’s denial shouldn’t surprise us today, especially in the era of #MeToo. Last year, when Jocelyn Gecker published a piece in the Associated Press detailing nine allegations of sexual harassment made against singer and administrator Plácido Domingo, Domingo would respond to Spanish daily paper ABC that the accusation of abuse of power “is as impossible as it is inconceivable.”

Metropolitan Opera general director Heinrich Conried bailed Caruso out of jail, telling the reporters who had gathered that no man of Caruso’s standing would be guilty of harassment. “A man like Caruso, of the highest honor and dignity, could not have done such a thing. If he desired it, he could have had the acquaintance of many fine women in this country. Any man might accidentally touch a woman when passing her, and if Caruso touched this woman he certainly must have done it accidentally.” (In 2019, the current Met general manager, Peter Gelb, initially stood by Domingo in a similar way, telling a group of Met employees he felt the AP story lacked “corroboration” because there were no other media reports of the accusers’ accounts. NPR pointed out that, in the AP’s original story, it had corroborated victim’s accounts through over three dozen interviews with colleagues, family members, etc.)

Despite the volume of real-time coverage (it merited daily headlines in the Times through the end of November and at least weekly reports through the end of 1906), the Monkey House Incident is a maddening case to parse out. There is evidence stacked against Caruso, based on both police reports and Caruso’s own interviews. Writing about this case for The Believer in 2004, David Suisman shares some of the highlights from earlier Caruso profiles. In 1903, one reporter quipped: “Caruso’s first love was garlic, and his second was young American women.” A 1905 piece noted “it might be apropos to chronicle that Signor Caruso likes our American oysters.… and the American women!”

Most damningly, in the same year as the Monkey House Incident, Caruso had discussed in one interview his flirtations with Met costars Olive Fremstad, Lillian Nordica, and Marion Weed—including chasing them around backstage during performances.

“It is said that you kiss all the beautiful girls that let you!” the reporter remarked.

“I kiss the homely ones, too” Caruso replied, calling that part an act of “penance.”

Caruso’s defense attorney, A. J. Dittenhoefer, had his work cut out for him. But the prosecution, led by deputy police commissioner William James Mathot, did not have an easy time of it, either. It was soon discovered that “Hannah Graham” was not the real name of the woman who was forced to file a complaint, nor was the address in the Bronx her real address. This made her seemingly impossible to find in time for trial.

Then there were the very real suggestions of racism and police corruption. Dittenhoefer highlighted this as part of his defense, suggesting that, since Hannah Graham was impossible to find, she could very likely be a conspirator with Caine in an effort to trap and discredit Caruso (this would not be too far off from the singer’s actual extortion by the Black Hand in 1910). That Mathot called the Italians who gathered in the courtroom to support Caruso a “crowd of perverts and curs… from the lazaretto of Naples” didn’t help optics, either.

Nevertheless, on November 24, Caruso was convicted and ordered to pay the maximum fine at the time of $10 (roughly $275 by today’s standards). For the highest-paid singer in the world, the money wasn’t the issue; it was the far greater purchasing power afforded by his image, which for the 33-year–old tenor was reaching its zenith.

Caruso was granted an appeal but lost. A second appeal was discussed, but by then the trial of the moment was superseded in headlines by the trial of the century: the case of Harry K. Thaw, who in a jealous rage over his wife, Evelyn Nesbit, had shot Stanford White in June of that year. (Nesbit would later testify that Thaw had done this in a rage over learning that White had assaulted her five years earlier.)

Despite his conviction, Caruso bounced back fairly quickly. Conried, who sided with Dittenhoefer, told the press that he’d “not even contemplated making any changes at the Opera House in consequences [sic] of the verdict.” (For the Met’s part in 2019, Domingo eventually withdrew from his planned appearance that fall in “Macbeth,” and said he would not return to the house.)

“It was telling how little Caruso’s conviction mattered,” Suisman writes in Selling Sounds. “The real verdict came…not at the courthouse, but at the opera house.” His 1906 season debut, in a performance of “La Bohème” on November 29, was sold out (when this news was announced in the box office, the Times reported “there was almost a riot for a few minutes, and some of the women in the crowd were roughly treated”). Scalpers sold tickets for as much as $20—double the fine levied against Caruso by the Yorkville Court.

He had support as well from many of his Met costars, many of whom signed a letter protesting his innocence that Conried then leaked to the press (the names of all signatories were redacted). Giacomo Puccini opined “that the whole thing was a put-up job by some hostile impresario.” When the Times asked Caruso if he thought he would have issues entering the United States the following year due to his police record, he shrugged. “I will get my money just the same,” he said.

The incident gradually became an inside joke. James Joyce immortalized it in Ulysses (“I wonder they don’t arrest the monkeys in New York,” Joyce wrote to his younger brother Stanislaus). Greeting cards that read “Where did Caruso touch the lady?” opened up to reveal a monkey on the inside with the caption, “In the monkey house.” The merchandising around this story reveals the throughline of memes in an era before the internet, replete with popular song parodies:

Mother, mother, may I go swim?

Yes, my daughter, do so.

Hang your clothes on a hickory limb,

But don’t go near Caruso.

While Edward Bernays was just 15 at the time of the Caruso trial, he was living in New York. Witnessing this trial—and the reporting thereof—must have gone a long way to shaping his later works detailing his theory and methodology around PR: Crystallizing Public Opinion and Engineering Consent. Looking at the “a priori judgment of any public,” he rationalized in Crystallizing that the work of publicity was to “either discredit the old authorities or create new authorities by making articulate a mass opinion against the old belief or in favor of the new.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Attempting to sort out the truth of the events in the Monkey House and its ensuing trial is an endless puzzle of truths and half-truths and good-faith and bad-faith and outright faithless actors sidled up against engineered consent, discredited authorities, and new authorities who were articulated, but perhaps not authenticated. More complications arise when reading post-trial news coverage, including the reveal of Mrs. Hannah Graham to be Hannah Stanhope. Along with her husband, a retired baseball player, Stanhope fled her home the evening of Caruso’s arrest and spent each subsequent night either with friends or in a hotel under an assumed name. In telling Stanhope it was her civic duty to make a legal complaint, Caine had tacitly implied that duty would also include shouldering the burden of public notoriety as plaintiff number one.

She had reason to be reticent. Several women (wearing heavy veils to protect their identities) were brought into the courthouse as part of the proceedings, prompting Dittenhoefer to ask, “How many strumpets can you bring here?” Caruso may have presaged #FakeNews, but it was an anonymous Times editorial published in response to Dittenhoefer’s comment that December that serves as an early analogue to the 2018 hashtag #WhyIDidntReport:

Is it to be wondered at that women witnesses are difficult to secure in any criminal trial? There is seldom protection from the court to guard any woman from oftentimes brutal, degrading, and irrelevant questions put by lawyers whose only excuse is to bring out all or any facts which may not be known to them at the time, and for which they are ‘fishing.’ Such excuse is generally a thin veil to discredit a witness, whether at the expense of the honor of the woman or not, seems to be of no consequence to the trial officers.

In this regard, not much has changed since 1906. While Caruso’s arrest was, for its time, a trial more on the level of Harvey Weinstein than Plácido Domingo, the comparative smallness of the opera world today doesn’t make going on the record any easier. In fact, the close-knit nature of the industry only makes it harder. Gecker’s AP report was predominantly framed around women who spoke on condition of anonymity. Much of VAN’s own reporting on classical music in the age of #MeToo has only been possible because sources were able to remain anonymous (though their stories were corroborated with additional interviews, email records, and in one case even a video of the assault).

Gelb cited anonymity as one reason to not cancel Domingo’s Met contract, believing that such reports “lessen[ed] the veracity of their allegations.” But one woman—Patricia Wulf—went on the record, and gave follow-up interviews to the New York Times and NPR. Another singer, soprano Angela Turner Wilson, had also gone on the record in a follow-up AP report.

The University of Oregon’s Jennifer J. Freyd has created a framing device for the type of response that usually comes from those accused of sexual misconduct or harassment when confronted about their behavior, DARVO: Denying the behavior. Attack the individual who makes the allegation. Finally, reverse the roles of victim and offender.

This was the pattern adopted by Caruso’s defense team (both legal and social). It’s a leitmotif repeated now by supporters of the conductors, singers, and instrumentalists whose names are discussed in connection to the #MeToo movement. Thanks to social media, it’s especially prevalent in the case of Domingo (who coincidentally made a Caruso tribute album early in his career: “Today’s great tenor sings famous arias of yesterday’s great tenor,” announced the original LP cover. It’s an apt metaphor).

Consider one denial tactic of Conried in 1906: “A man like Caruso… could have had the acquaintance of many fine women in this country.” Consider, too, a similar denial used in an email sent to Boston Globe reporter (and VAN contributor) Zoë Madonna, in response to her Domingo-related op-ed in 2019:

Plácido Domingo did nothing wrong – big deal, he invited a few performers back to his apartment and may have had a stray hand now and then.… All of you progressives beat the same drum and are happy to ruin the careers and lives of talented men all because of a few wayward steps – sorry but the punishment does not fit the crime! This young woman here looks forward to going to see Domingo in Salzburg this summer. Oh, and if I am lucky, he may glance my way.

Denial quickly merges into accusation. Caruso even threatened to sue the city over his arrest, stating emphatically:

I am entirely innocent. The arrest and charges made against me were a complete surprise. There is no foundation for it whatever, and I am confident that I shall be thoroughly and completely vindicated. That I am highly indignant at the outrage committed goes without saying, and I do not mean to let the matter rest.

While Domingo initially apologized for the allegations detailed by the AP, he later walked back on his statement in order to “correct the false impression” it had created. “My apology was sincere and wholehearted. But I know what I haven’t done, and I will deny it again.” (In the case of Domingo’s colleague, James Levine, who was fired in 2018 by the Met following accusations made against him, Levine actually did sue—the case was settled a year later.)

Conspiracy theories take over the thread in both Caruso’s and Domingo’s cases, providing ample ground for accusation that soon becomes reversing the roles of victim and offender. One letter sent on Caruso’s behalf to the Times came from a Rochester man who had recently visited New York. He detailed his own visit to the monkey house, where he saw what appeared to be a policeman, in lieu of an arrest, “endeavoring to get [a man who seemed to get too close to a woman] to make a settlement with the woman” suggesting an off-the-books bribe took the place of due process.

“In closing, the Rochester man said he thought from the descriptions he had read that the woman he saw and ‘Mrs. Hannah Graham’ might be one and the same.”

“Eros has a tremendous force, as well as a subtle yet thoroughly arousing power, and it is used by both sexes. It is precisely that power that is now threatening to doom the old man,” wrote Maria Ossowsky of the Domingo allegations in a commentary for the German radio station SWR. “The case shows how mercilessly a quick-to-judge, sometimes morally acidic ‘erotic police’ attack a person and destroy his life’s work.”

While Caruso’s fans had the Met and the courtroom, Domingo’s have a greater form of mass distribution: the internet. Multiple groups on Facebook have cropped up in the last year with the mission of supporting Domingo following the AP report. One of the most active, We are with you Plácido!!!, has nearly 3,000 members and posted 72 times in the last month. This math is not in Patricia Wulf’s favor. After the AP story broke, one fan very quickly found and posted Wulf’s LinkedIn profile to the group, noting that she mentioned Domingo’s name in her bio with the caption “That’s scum!!!!” Other selected comments illustrate the domino effect of DARVO:

“He should sue her for libel. She seriously made an effort to damage his career without any proof.”

“And how she squeezed tears during reportage for Euronews… The highest level of hypocrisy…”

“[W]e should know that she illegally uses the name Plácido for personal purposes.”

“A user and then an abuser! A liar and I am certain an untalented singer. Always the same story for her 15 minutes of fame. ! Am [sic] immoral creature!”

Domingo and Caruso make for compelling symmetry in the last century of #MeToo, but it’s not a perfect comparison. For starters, as Anne Midgette points out, Caruso got one thing that Domingo did not: “He got caught.”

While chief classical critic of the Washington Post (a position she left last fall), Midgette spent seven months, alongside colleague Peggy McGlone, reporting on sexual harassment and misconduct in the world of classical music for a piece that ran two years ago this month.

Fueled by interviews with over 50 people, Midgette and McGlone’s piece was a juggernaut: multiple, on-the-record reports by identified victims of abuse from musicians and administrators that included Cleveland Orchestra concertmaster William Preucil, conductor Daniele Gatti, and manager-director Bernard Uzan.

But, Midgette points out, there was little satisfaction to be had in these outcomes, especially for the victims. While Preucil, Gatti, and Uzan all lost prestigious jobs (Uzan resigned), Gatti was then hired—in the same year—as music director for the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma. Last week, it was announced that James Levine will return to conducting at Florence’s Maggio Musicale Fiorentino this winter.

“This is a very insidious theme in journalism and all these stories,” she explains. “We’re telling stories about people [where their abuse] had been known for years and years, decades. And yet, when it was printed in the paper, it became a thing. And then it became a case that you could judge. And then they lose their jobs. And I had people who knew about this behavior ten years ago looking me in the eye saying, ‘Nothing was proven, he promised not to do it anymore.’”

In terms of sexual harassment and assault, the justice system—which, no matter how his case is viewed, was seemingly broken even in Caruso’s era—has in some ways grown weaker for victims. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which oversees workplace cases of sexual harassment. But ogling, catcalling, and any form of harassment that’s not classified as rape or assault is no longer a crime in the United States in the way mashing was. While sexual harassment is a violation of federal law, in many states it doesn’t protect freelancers (which is how many artists in the American classical music industry are classified).

What’s more, those who are protected by sexual harassment laws may be caught in a morass of statues, confidentiality clauses, and paperwork. The process now stretches the concentrated span of Caruso’s arrest, trial, and conviction across years, creating protracted legal battles. Settlements become the preferable means of both protecting the identity of victims and allowing them to move on with their lives. But they also leave the perpetrators, even those who get caught, in power and in control of the narrative. As former Harvey Weinstein attorney Lisa Bloom wrote to him in a 2017 memo: “It is so key from a reputation management standpoint to be the first to tell the story.” Bloom’s methods of “positive reputation management” came from the same DNA of Bernays’s “engineered consent” a century earlier.

Perhaps this is the real story of the Monkey House, and of Domingo: The real inch of truth in both isn’t in a careful documentation and examination of what’s real. It’s in an equally careful documentation and examination of what happens when truth is spoken to power. There, the entire system of complicity and enablement of that power is unveiled. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.