How many years should pass, in polite society, before a country is allowed to have its own national style of classical music? In 1939, over 150 years after the Declaration of Independence, Leonard Bernstein began his senior thesis at Harvard with the statement, “I propose a new and vital American nationalism.”

In the essay, “The Absorption of Race Elements into American Music,” he set out to define that aesthetic nationalism. The title makes his view clear: that American national style should be founded on Black musical culture.

This idea was still new in 1939. Dvořák, who first pointed out, in Bernstein’s words, “that America had a great treasure of material that had never been used” in Black music, was still a living memory. (Bernstein added that most of the themes in the “New World” Symphony “sound more Slavic than anything else.”) Still, Bernstein’s definition of national style is sympathetic to Dvořák’s; Bernstein makes the important point that “it must be organic,” adding that the music should sound “typical of the country” of origin, meaning “an American feeling, or tempo, or rhythm.”

To Bernstein, that “American feeling” should come out of jazz (the blues and 19th century dance music barely track for him). He goes into precise musicological detail about what he considers the scales and syncopations of African-American music and how they were being used in his era by composers like Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Roger Sessions, Charles Ives, and others. Bernstein was barely as old as jazz at the time, so his thesis includes a lot of forcing notes and rhythms into standard, equal-tempered scales and 4/4 metric notation, and he never considers ragtime, which had dropped in popularity. Still, he roughly captures the swing music of the pre-bebop era.

There’s a key section titled “The Integration of New England and Negro Strains” that brings in what he says is “the only other strain that can be said to have reached any universality” in American music: regional spirituals and folk music, that composers like Roy Harris and Charles Ives “combine with certain features” of Black music. This is where the essay—which is smart and thoughtful, though of course necessarily a little naïve—gets interesting for the 80-odd years that have followed Bernstein’s graduation.

Those years saw the fruition of his genius, not just his extraordinary musicianship but his public presence and his skill at advocating for music: taking his own insights into and excitement over it and instilling that enthusiasm in the public. He was the most important American musician of his era, and essential to the presence of Copland, Ives and Harris on the American scene. To those names add William Schuman, David Diamond, Walter Piston and Peter Mennin.

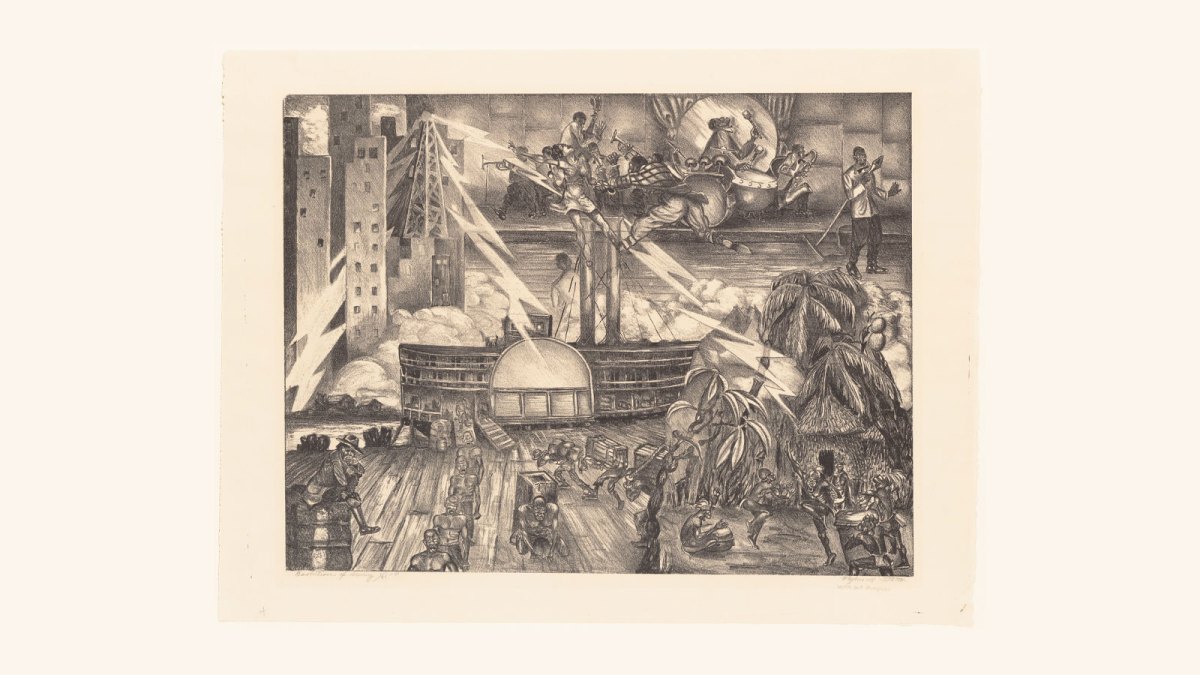

Those composers and others established a unique, important, and now strangely neglected style in American music. This second generation of composers took the idealized, myth-making sounds of Ives, Copland, and Harris, which tended to evoke the imagined white-ethnic pastoralism of small-town life and endless western expansion, and put them into the America they saw around them. This America was increasingly urban, saturated with mass media, dotted with steel skyscrapers, and connected by jet travel. Schuman, Diamond, Piston, Mennin and their colleagues wrote streamlined, rugged, technicolor music that seemed powered by the international might of the country. This was also idealized music—confident in material progress and the assumed triumph of democracy over fascism—but it abandoned the myth of America as made up of small, rural towns. It reflected the sensation of people rubbing elbows on the sidewalks and in the subways, and the beauty and ache of urban isolation in the paintings of Edward Hopper and George Cukor. It was organic; it was the American feeling, tempo, and rhythm; and it was made nowhere else. That was key.

Bernstein was an essential advocate for this style, especially Schuman. Bernstein placed it directly in front of the public, establishing the American sound as not just modern but central to classical music in this country. The concurrent contemporary revolutions from John Cage, Morton Feldman, and later the minimalists became a de facto international style, American made but export quality avant-gardism. (Steve Reich and Philip Glass are famous as American composers, but the sound of the music itself has been easily adopted globally, removing geographic and cultural roots.) This was not musical nationalism, and Bernstein barely touched it. Nor were the works of Black composers like George Walker and Julia Perry, very much part of that American style, on the conductor’s radar.

Music develops like science, accumulating knowledge and tools. During Bernstein’s life, the Black music he saw as so essential to the American style continued to evolve, leading organically to rock and soul. After another 20 years jazz was essentially a musical niche, where it has remained, while hip hop was on its way to becoming the dominant popular music in the country, if not the world.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

How can we update Bernstein’s essay? Has new Black musical culture continued to influence the American national classical style that he described? Not in any appreciable, lasting way, mostly because that American style has largely disappeared from music schools and concert halls, as if it were some kind of kitsch. It’s much easier to hear modern American music in concert this century, with drastically improved representation of women and non-white composers. But the American style as Bernstein heard it has been mostly replaced by music that is made by American composers but could come from anywhere.

The only real and consistent exceptions to the disappearance of the American style are contemporary Black composers: Carlos Simon, Valerie Coleman, Terence Blanchard, Anthony Davis, and Adolphus Hailstork. These composers are writing music that preserves and extends the “national” style exemplified by Schuman, Diamond, Piston, Mennin—and, more to the point, George Walker, who is finally getting more posthumous performances, and Julia Perry, whose centennial is this year. And these contemporary composers are doing it with the same organic feeling Bernstein recognized in 1939: that this is the sound of the country. Pieces like Simon’s “Fate Now Conquers,” Coleman’s “Seven O’Clock Shout,” Hailstork’s “An American Port of Call,” and Blanchard’s and Davis’s operas all embrace the sounds and materials of Black popular music through the decades. Crucially, they also wield the harmonic innovations of American music from the mid-20th century: stacked chords that hold a tonal center and are both complex and transparent (it’s an enduring idea that has been a staple of modern big band jazz composing through to contemporary musicians like Darcy James Argue and Miho Hazama). There’s an inner strength to this sound that powers rhythms and phrases, and that comes together in music that mocks the artificial distinction between modernism and populism.

That this style has gone so out of favor is a shame; that Black composers are keeping it alive is apt. What Bernstein didn’t see in his essay, but is clear in 2024, is that American culture across the board is an ongoing experiment in modernism, in taking apart old ways of organizing society and remaking them. The great jazz musician Kahil El’Zabar expresses this best when he describes the origin and purpose of his Ethnic Heritage Ensemble, founded 50 years ago. El’Zabar came up with the name after observing the frequent celebrations of white ethnic heritage in the U.S. and realizing that Black culture since Emancipation has been creating its own ethnic heritage. Not only has that been, again, essential to overall American identity in music, fashion, food, and more—it’s been a contemporary and forward-looking modernist project.

Bernstein didn’t yet recognize this: It’s impressive that, barely into his 20s and at Harvard no less, he was able to think deeply about music that in 1939 was still mostly mocked and shunned by the gatekeepers of “high” culture. In 2024, it is clear that American popular music is at the vanguard, because it came from people constructing their own modernity. On some level, Bernstein felt that. He understood that popular music was the sound of the country.

The pastoral idealization of America continues even as the nation grows more urban. There are very real political dangers in this country, driven by a revanchism that is fighting to keep power centered in myth, and that fears the life of cities and the people in them. But the energy that fuels American contemporary music comes from the modernism of urban life and culture: from city streets, from all sorts of different people crossing paths, from cars going by blasting merengue and drill. And there is where the music of these composers matters beyond just music. As Nikole Hannah-Jones has pointed out, America didn’t really become a democracy until its Black citizens had de facto political rights, and those are currently threatened. When Simon, Coleman, Hailstork, Blanchard, and Davis make these organic American sounds in their music, they’re arguing for what America is, and also what it should be. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.