“Life here is a John Cage score, dissonance made eloquent.”

Bill Hayes, Insomniac City

“This text is a mosaic of remarks,” begins the Florent Ghys composition “An Open Cage.” When I first hear it, I mistake John Cage’s voice for essayist David Rakoff’s. They share a raspy, disaffected tone, a soft sibilance that exudes ironic detachment. At times, they sound as though they are wincing. I have heard Rakoff on the radio numerous times; I have seen him on book tour. I have always envied the way he speaks. His voice is both rich and delicate, honeyed, like a piece of baklava. He shares his thoughts with calm certainty, a quale I hear echoed by Cage.

The song continues, Cage stringing together assorted excerpts from his diary while Ghys’s bass line underscores each syllable. “Satie was right, experience is a form of paralysis. I’m gradually learning how to take care of myself.” A guitar chimes in and mimics his phrasing. Percussion forms the backbone of the movement and a choir eventually drowns out the single voice.

What I know of John Cage can accurately be summed up by all three movements of his iconic “4’33.″ This winter I was asking around for music recommendations when a friend mentioned the Bang on a Can All-Stars. Discovery algorithms have been chafing me. With the world a mess and the days dark and short, I need something fresh, so I queue up “Field Recordings.” With Cage’s opening words, I recognize instantly that this man is a homosexual. I may mistake who he is, but I know unmistakably what he is.

Florent Ghys, “An Open Cage”; The Ban on a Can All-Stars

Somewhere amidst pornography in my Tumblr feed, I see a post that says, “Only queer people have gaydar. Straight people have stereotypes,” and I laugh. Lots of men can sound gay to the untrained ear. However, there is to my mind one trait that differentiates the voice of a gay man from that of a straight man: that wincing. A heterosexual seems to speak with a momentum that comes from never having had to viscerally second-guess which words he chooses, never having felt his vocal chords tense for fear of letting the truth slip out.

Such tension can manifest in up-talk, over-pronunciation, sibilant S’s and numerous other affectations that homophobia trains us to loathe. Speech therapy is not uncommon for the homosexual male, unwillingly (as documented by David Sedaris in the essay “Go Carolina”) and willingly alike (as in the David Thorpe film Do I Sound Gay?). Sex columnist Dan Savage, in an interview for the latter, states bluntly that the aversion to “gay voice” and its effeminacies is rooted in misogyny. Even other gay men will balk at feminine speech patterns displayed by their peers, or hate it within themselves. In our circles there is pressure to conform to a masculine hegemony: “straight acting,” they call it and deride those of us who open our mouths to let a purse fall out.

Cage, while not exactly out in the modern sense, often challenged dominant expectations. The only music for which I knew him previously is iconic for its defiant use of silence to encourage its audience to listen. The absence creates a negative space with a gravitational pull. Or at least that’s how I read queer historian Jonathan Katz when he notes how the composer “stood before the fervent Abstract Expressionist multitude and blasphemed, ‘I have nothing to say and I’m saying it,’ ” in the essay “John Cage’s Queer Silence Or How To Avoid Making Matters Worse.” Living and working amidst mid-century homophobia, perhaps Cage didn’t need magic words like I am gay to define his enduring relationship with dancer Merce Cunningham. He imagined dissonant forms of expression.

Homophobia, though—or rather, its predominance—is exactly what draws me to gay voices. They entice me. I feel safe among men who sound like me—or at least as safe as I can these days. Donald Trump’s America, a presidency that has doused the fires of misogyny with gasoline and is colluding with a vehemently anti-LGBT vice president and Supreme Court nominee, appears to be closing in again upon those of us who over-dentate our T’s and enjoy wearing a sensible black pump from time to time. It’s a constriction that has prompted many of us across the nation to march and shout in protest. Of course, I’d be remiss to understate complications within gay spaces—they are rarely devoid of misogyny and racism—but there I feel at least safe enough to speak without second guessing how I do.

Few people admit to liking the sound of their own voices, but for homosexuals this aversion can run deep. For myself, it inspires me to pathologize my nasality, my fits and starts. This occurs to me as I listen back to a recent telephone interview with photographer and writer Bill Hayes. He is expressing how his relationship with neurologist and physician Oliver Sacks—who, like Cage, kept his sexuality oblique for the longest time—finally got him to keep a diary. Bill’s voice is warm and comforting and invitingly gay.

“I started a journal because Oliver himself, God bless him, said to me, ‘You must keep a journal!’ ” Hayes is getting ready to release his memoir Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me into the world, and I am covering it for the book news source that I work for, Shelf Awareness. He sounds charming and confident, any wince he may have acquired growing up in devout Catholicism seems to have smoothed into a proud signifier rather than a thorn in his side. By comparison in the playback, the timbre of my own voice sounds uncertain, even fraudulent. It wavers with anxious energy.

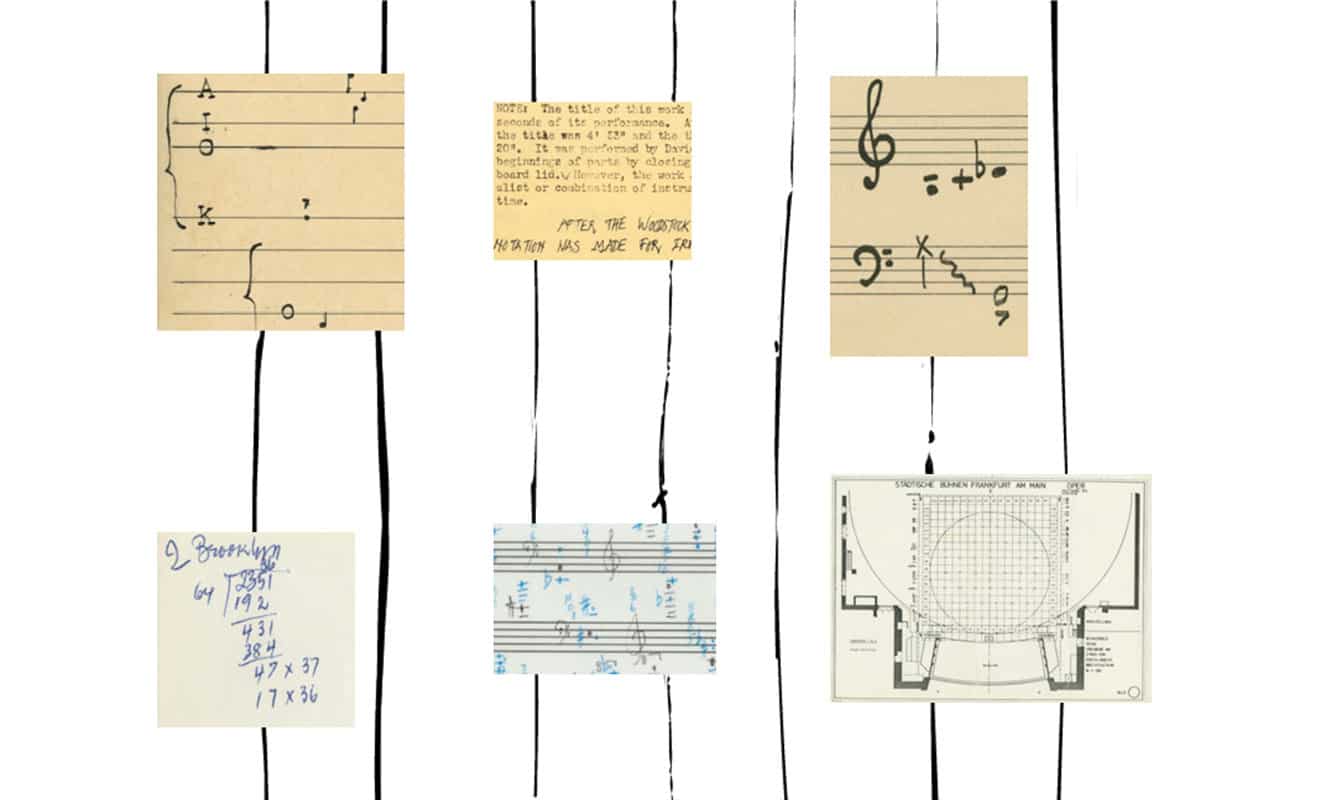

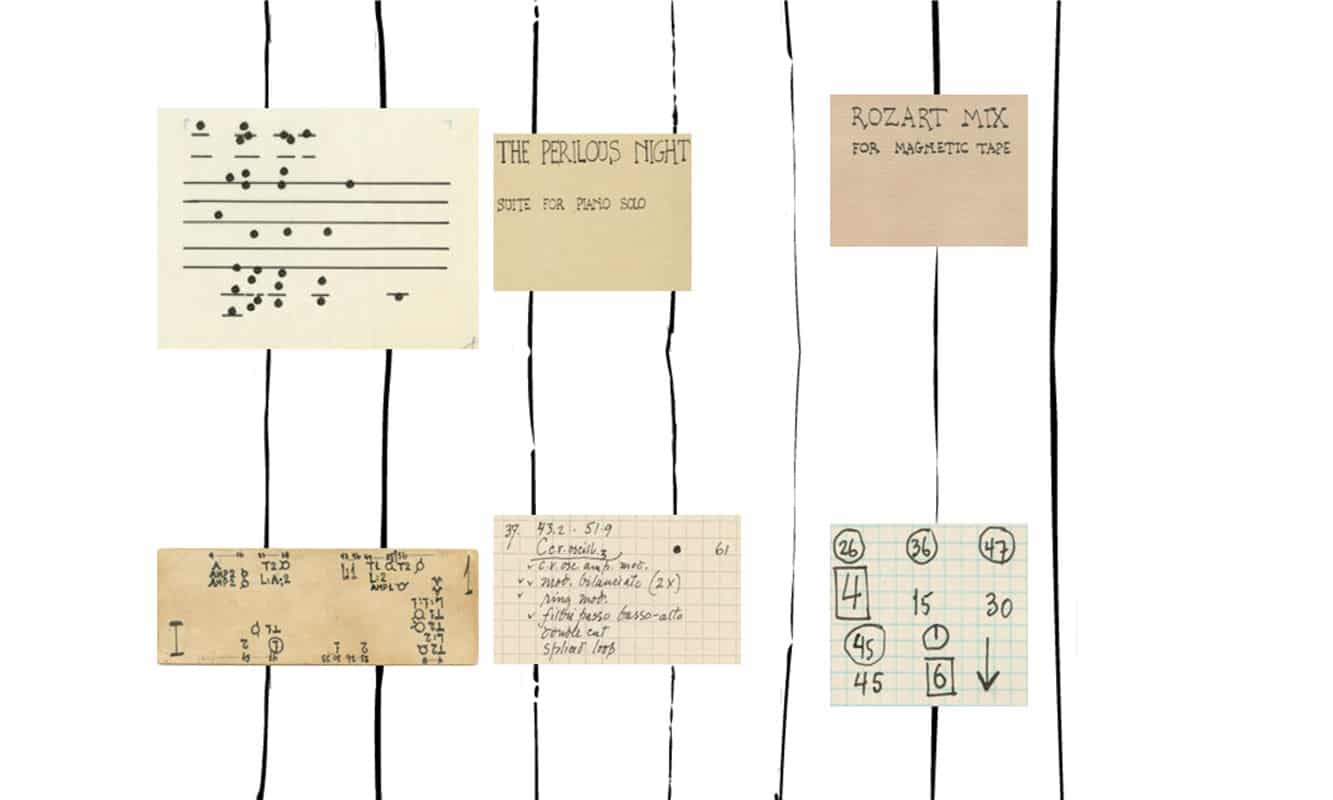

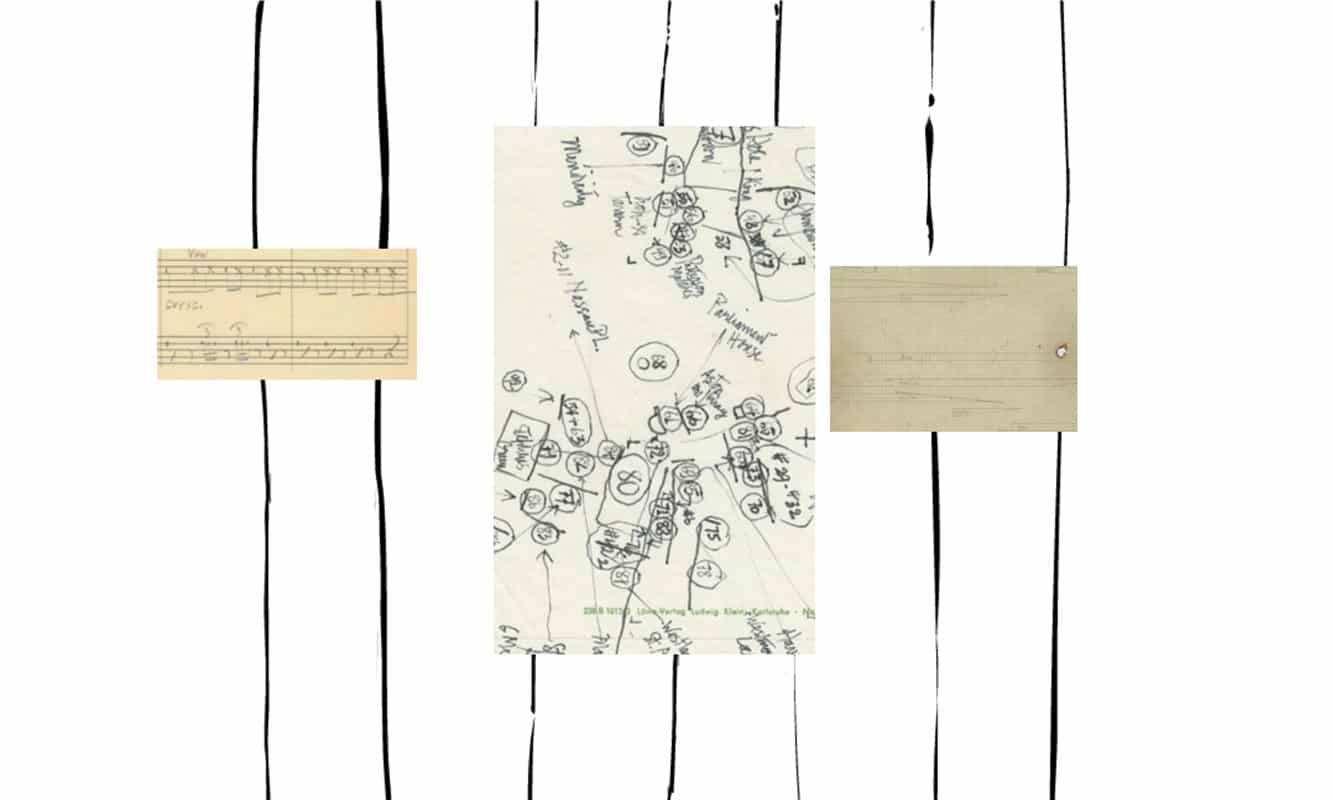

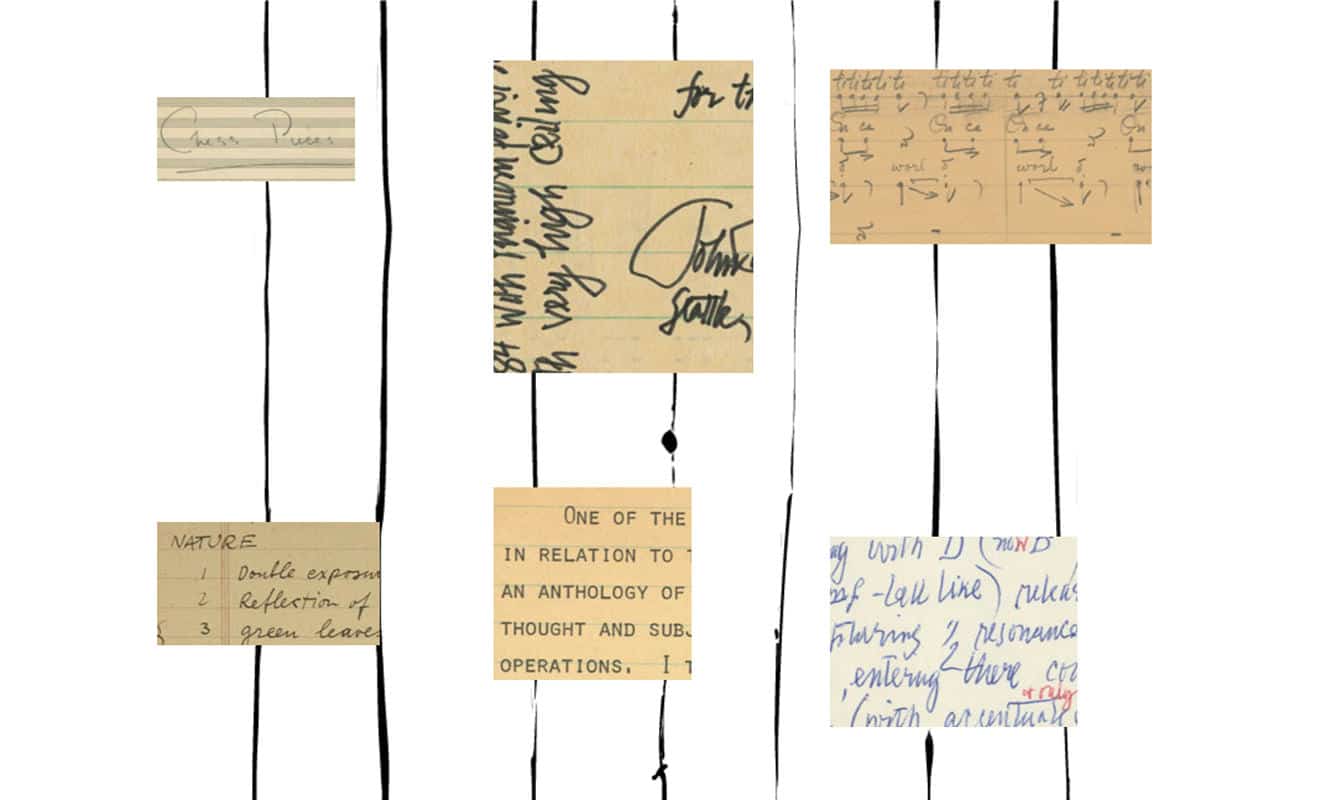

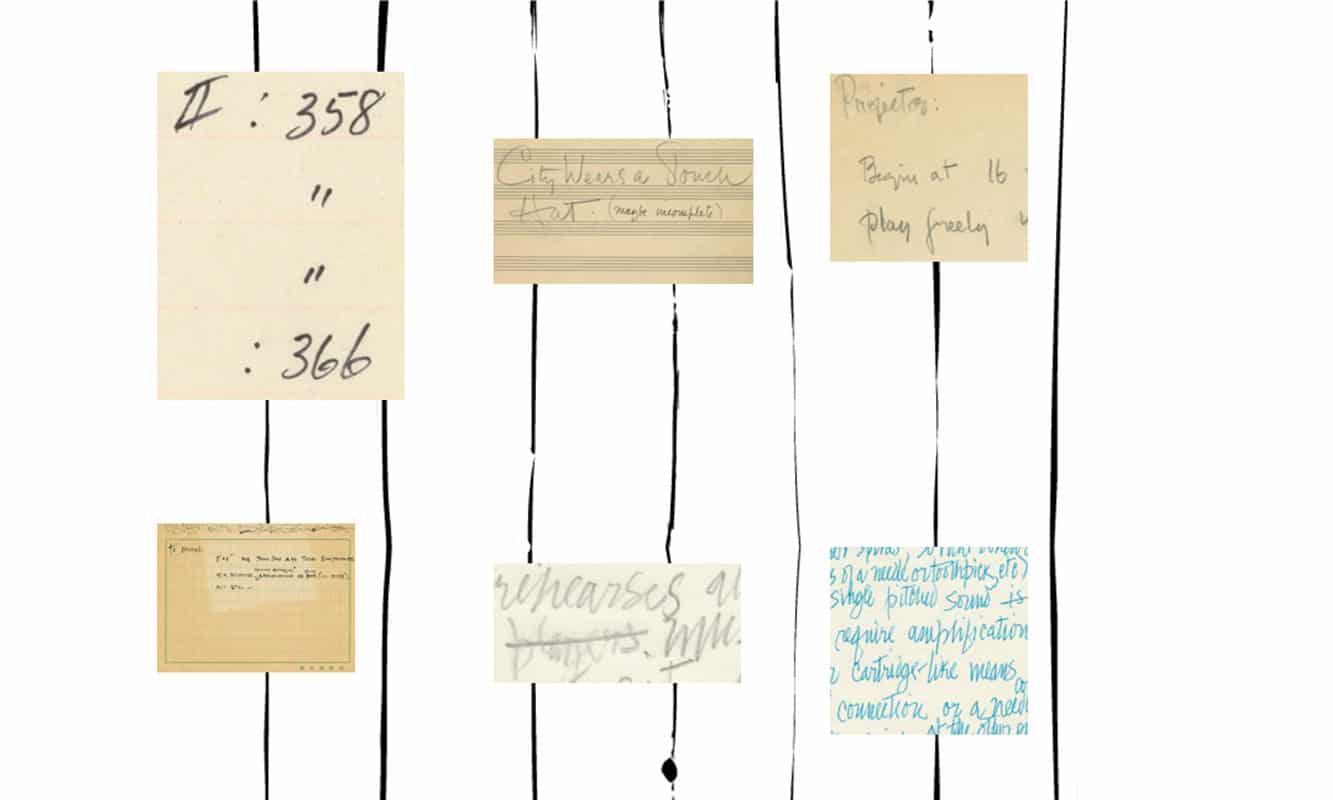

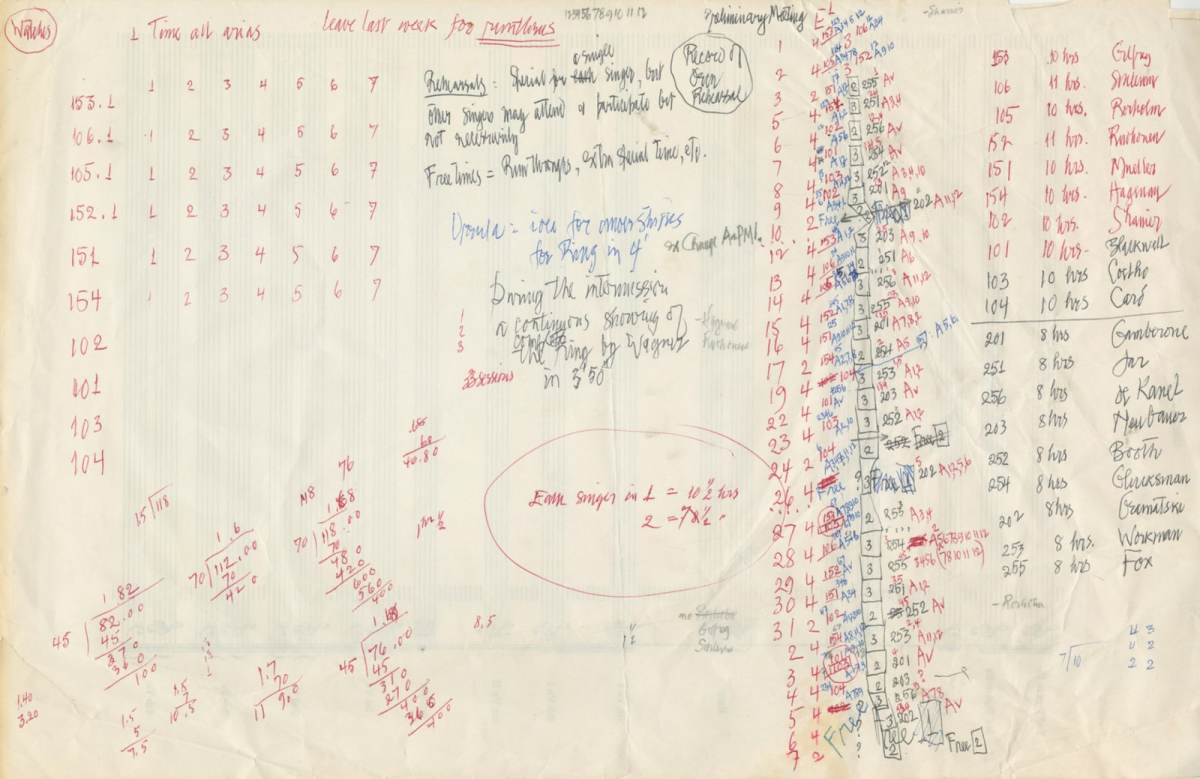

“Oliver was an inveterate journal keeper,” Hayes is saying, “and in his archives there are a couple thousand journals that he wrote in his lifetime. I kept a journal in a less methodical way than he ever did. Mine consisted of scraps of paper, entries written on the backs of envelopes, small notepads that I would buy occasionally, and then ultimately diaries that I kept on laptops; these scattered fragments chronicled my life in New York and with Oliver.”

The description of Hayes’s diary-keeping reminds me of John Cage’s mosaic approach. The text for Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) is constantly interrupting itself, scattering related anecdotes against a changing sea of formatting. Yet to hear Cage read from it in his sweetly viscous voice amidst the musical swells of “An Open Cage,” his eloquence inheres in the dissonance. And it is beautifully alluring.

Inspired by Hayes and Sacks, I buy myself a five-year diary on my 30th birthday. Not because I think of this age as any special milestone. I just happen to be at a point in my life where I want to document my days better. Memory isn’t failing me, but how curious will it be to reminisce with such an aid? My diary is no larger than a mass-market paperback, though clothbound in a tasteful blue. Each page represents a single date and has room for five entries, one for each year. The idea is that, as I write, it is easy to reference what I did exactly one, two, three and four years prior. An impressionistic log of what has stood out to me. Cage’s Diary divides single years into month-like installments, but the eighth, which forms the basis of Florent Ghys’s composition, took from 1973–1982 to write. In its introduction, he blames the Nixon administration: “Like many other optimists I was struck dumb by the course of current events.”

I know the feeling.

The Trump administration conducts itself in falsehoods, relying on our cultural willingness to forget in order to achieve its agenda. His inauguration was the most well-attended in recent history—except that it wasn’t. His immigration reform isn’t a Muslim ban—except that it is. His cabinet and cronies foster a profound sense of paranoia, so that facts not aligning with the White House’s statements are dismissed as fake news. In Cage’s case, such experience with current events became a form of paralysis, rendering him unable to keep his diary.

However, taking a page out of Hayes’s book, I am rather inspired to resist such writer’s block, which can be manipulated by those who would capitalize on amnesia. I am gradually learning how to take care of myself, one method being to embrace a queerness that subverts misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia and racism, hallmarks of the Trump hegemony. In five years the democratic landscape may shift monumentally, and my little diary will be my reference guide for it. By then, perhaps the wince in my voice will have smoothed into a fuller, warmer sound—but no less gay. I never want to lose my place in the sibilant choir making dissonance in this time of rising fascism. ¶

Comments are closed.