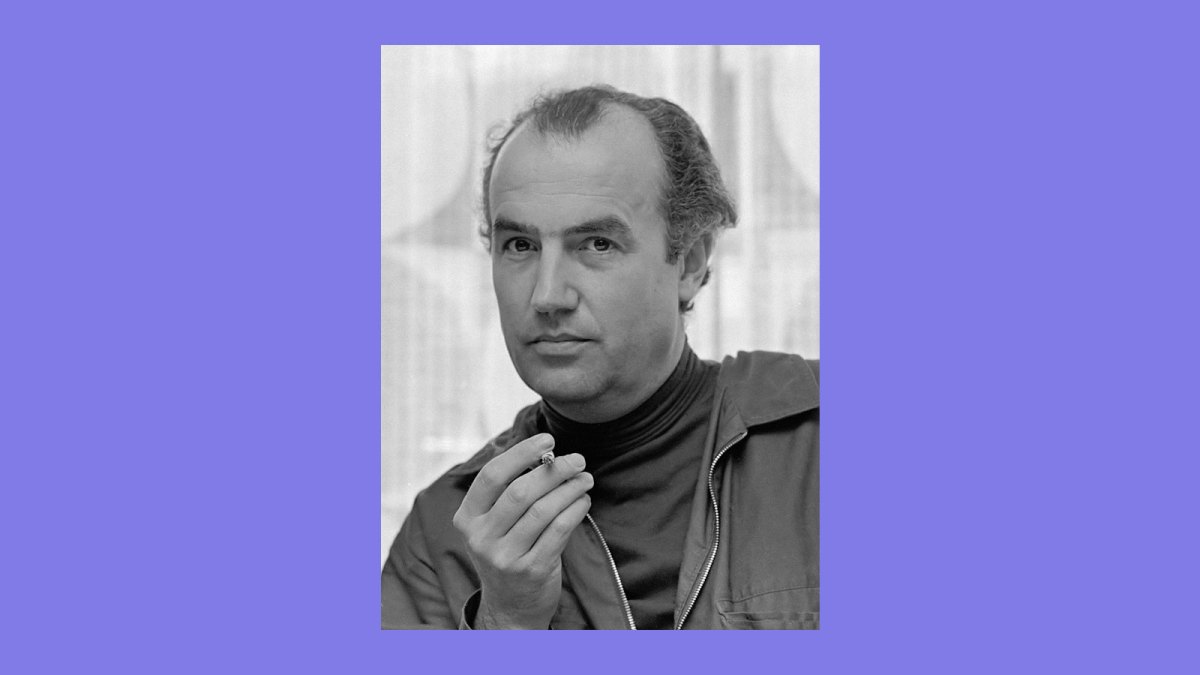

Luigi Nono would have turned 100 on January 29. He was born, raised, and died in Venice, whose tradition of separate choirs performing from different places within the church had a profound impact on the composer’s sense of sound, space, and silence. Despite this relationship with the past, few musical oeuvres have quite as palpable a connection to the impersonal violence and personal alienation of the 20th century as Nono’s, where impassioned political pieces—he joined the Italian Communist Party in 1952—coexist with fragile works, whose pleas never rise above a whisper. Composers who used the serial technique are sometimes portrayed as shutting themselves off from the world to focus on mathematical games. Nono wrote serial music, but he stared the world in the face. He once accused John Cage and others who left aspects of their music to chance of “being afraid of their own decisions and the freedom that they imply.” I don’t think Nono was right about Cage; still, the Italian was a composer who faced the vacuum before the music with rare courage and integrity.

“Il canto sospeso” for voices and orchestra (1956)

By using letters from the condemned of the European resistance to Fascism as the text for this piece—spoken plainly and sung—Nono rejects allusive, intellectualized, absurdist, or otherwise indirect language to memorialize the exterminations of World War II. “In the early mornings, we are forced into the forest to work,” one letter reads. “My feet bleed, because our shoes have been taken away.” The sixth movement is especially terrifying in its austere brutality, but Nono does not rob his victims of their capacity to perceive beauty, also creating musical passages of delicate warmth.

The approach is reminiscent of Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Secret Miracle,” in which a Jewish writer in Prague, condemned to death by the Nazis, is granted time by God to complete his final book: “The physical universe stood still… In his mind a year would elapse between the command to fire and its execution.” In the ninth movement of Nono’s piece, titled “…addio mamma,” time coalesces into a texture of high strings, percussion, and female voices. The movement lasts less than five minutes, but feels like an embracing forever.

“La Fabbrica Illuminata” for voice and tape (1964)

Nono was a Communist, but had no interest in the naïve corners of Communist art. “La Fabbrica Illuminata” turns speech, song, and especially the noise of the factory into soundscapes chilling in their indifference to the limits of human biology. This is music that sounds like what it must feel like to rub a piece of steel against your teeth. At the same time, brief passages of exquisite monody and vocalization remind us just what beauty industrialization and dehumanization risk stealing from us.

“… sofferte onde serene …” for piano and magnetic tape (1977)

Nono composed this work after a creative and personal crisis brought on by the deaths of his parents in close succession. “An unutterable silence descended: that is to say, I did not possess the means I needed to express myself,” he said. Breaking that silence was “…sofferte onde serene…,” a piece from which Nono’s more introverted and profound later music begins to emerge. There is a placid uncertainty to these sounds, an acceptance of the unpredictability of the instant. “Life continues in the suffering and serene necessity of the ‘balance of the inner deep,’ as Kafka puts it,” Nono wrote about this piece, which achieves solace through timidity and reserve.

“No hay caminos, hay que caminar…..Andrej Tarkowskij” for seven ensembles (1987)

I consider fragility and violence to be two of the main themes of Nono’s music. This work synthesizes these two interdependent extremes of human experience. If you turn the volume down too low, you won’t hear anything except the terrifying outbursts; if you turn it up too high, you may damage your eardrums. “No hay caminos” spends little time in comfortable middles; the music is rarely mezzoforte, rarely in the comfortable treble. The outliers of hearing become the average.

Nono’s music is never exactly to relax to/study to, but this piece keeps you in a state of high alert. How can we let our guard down, the composer asks, knowing what we know?

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

“A Pierre. Dell’azzurro silenzio inquietum” for contrabass flute, contrabass clarinet, and live electronics (1985)

Pierre rhymes with Cher, and Boulez, the dedicatee of this work, is also immediately recognizable by a single name. Despite the ferocity often associated with Boulez, “A Pierre. Dell’azzurro silenzio inquietum” is an extraordinarily gentle piece, creating a hush in which these preternaturally soft woodwind instruments can unfold the subtleties of their timbres, aided by electronics and our fascination with their sculptural shapes. There is something prehistoric about the piece: Its world is one where keeping track of time remains a foreign, violent concept.

“Fragmente-Stille, An Diotima” for string quartet (1980)

The score for this work is marked with fragments from the poet Friedrich Hölderlin above the staves. At no point are these words intoned, but they inform the music in mysterious ways: no fragment quite as much as the phrase “Wenn in reicher Stille,” or “When in the rich silence.” The quartet is full of pregnant, prismatic pauses. Music that constantly starts. And stops. A lot—was not exactly rare in the 20th century, but Nono shows a microscopically refined sense of timing and proportion here. The interplay of sound and stillness never gets predictable or tiring by seeming to imply the piece is over. That allows the listener to keep her concentration on the sounds, which have a diversity of texture of the kind you can only appreciate when given enough space—over 30 minutes—to observe them closely.

“Intolleranza 1960” (1961)

This piece tells the story of a migrant, and the trials inflicted on him by a society whose general indifference is only interrupted by bouts of pointless cruelty. Nono dedicated the opera to his father-in-law, Arnold Schoenberg, himself forced to flee his home by the rise of the Nazis. Despite the date in the title, the sparse narrative of the opera remains exceedingly relevant. The unnamed Refugee is taken into custody; not unlike European coast guards today, the policemen wonder if they should throw him in the water to drown. In Act II, brief, chaotic rattles and swells from snare drums signal the perseverance of fanatical, fascist beliefs; early performances of the opera in both Venice and Boston were interrupted by right-wing agitators. When the refugee finally drowns, in the last scene of “Intolleranza,” Nono’s vocal polyphony summons Venetian Renaissance music. His home is a place that is always drowning. Somehow, it is still here. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.