Every year, when stores clear their shelves of Christmas kitsch and bring out Valentine’s Day paraphernalia, I feel what must be post-industrial existential dread. Paper plates send out X’s and O’s. Companies I’ve never heard of peddle plaques, keychains, and jewelry that can be “personalized.” My social media feeds suggest romantic dinners and getaway experiences that don’t always look terrible, but express a certain ethos: love should be Instagrammable, a shiny package complete with diamonds, wine, and crème brûlée. I hate the materialism and tedious commercialism, yet somehow I’m still a sucker for this holiday. As I write, I’m helping my four-year-old lick the messages off candy hearts and write on new declarations. He wants hearts that say “Snuggle!” “Let’s Play House,” and “I.L.Y.T.M.A” (I Love You The Maximum Amount). I’m still into love and love notes too.

In The Dying Animal, Philip Roth wrote that “love”—in quotes—“is the only obsession everyone wants.” His novel’s narrator, David Kepesh—a lecturer at a New York college who has slept with numerous female students but avoided emotional involvement with them—comes to this conclusion after love undoes him. Pining for 24-year-old Consuela Castillo (and longing for her to desire him sexually, not just intellectually), he observes: “People think that in falling in love they make themselves whole? The Platonic union of souls? I think otherwise. I think you’re whole before you begin. And the love fractures you. You’re whole, and then you’re cracked open.”

In the film version of The Dying Animal, “Elegy,” the musical accompaniment for Kepesh and Consuela’s affair includes the Adagio from Bach’s Concerto in D Minor, two of Beethoven’s “Diabelli Variations,” and most memorably, Satie’s “Gnossiennes” Nos. 3 and 4. The soundtrack is just right, given Roth’s passion for classical music and his subject as a writer. Classical music is in many respects analogous to the tugs, tortures, brutalities, and pleasures of sex and love.

To acknowledge the ascendancy of sex and love (“the only obsession everyone wants”) without clichés and market sentiment, I’ve matched types of love affairs to pieces of classical music.

Old Love

Dmitri Shostakovich: Suite for Jazz Orchestra, No. 1, Op. 38a, III. Foxtrot (1934)

When I hear the words “old love,” what comes to mind is Shostakovich’s lilting “Foxtrot,” with its horns and piano enforcing a strong, regular rhythm; sultry, crooning saxophone; sensuous violin; lap guitar conjuring a Polynesian luau; and a recurring big band sound. One minute it’s a march, suggesting a royal or military event, and the next it’s an erotic dance. Much has been said about Shostakovich’s Jazz Suites being too strict (not jazz) and embracing chintz. Still, the “Foxtrot” energetically manifests pragma (practical or longstanding love), with a splash of eros (sexual passion) and ludus (playful love). It’s orthodox and direct compared to music by Miles Davis and Charlie Parker, but music—and love—endorsed by the government is almost always that way. I’m not saying old love must be innocuous. I’m just saying it often thrives on official or public approval, and that it’s hard to argue with a mellifluous, jazz-inspired two-step.

New Love

Hauschka: “Bounce Bounce” (2012)

“Bounce Bounce” reminds me of a story my dad likes to tell and retell. Years ago, while tripping on LSD, he dug his fingers into his hair and felt his Afro unexpectedly start “growing” up to the sky in the most astonishing and strangely pleasurable way. Both my dad’s acid trip and “Bounce Bounce” call to mind the word “generative,” a late-14th century term, from the Latin generatus, meaning “reproductive, pertaining to propagation.” New love is nothing if not generative. It’s also effervescent and flexible. Filmmaker Hayley Morris, who made the music video for “Bounce Bounce,” focused on another word, “energetic,” and created a stop-motion tide pool in which barnacles discharge their feathery legs; mussels sporadically open and close their shells; sea urchins sway; crabs scuttle; snails rhythmically contract to crawl the sea floor; and seaweeds and algae gyrate and surge in the motion of the ocean. It’s a dynamic, rapidly expanding universe that’s infinitely more interesting than a time-lapse video of a rose blooming. Or even an acid trip. So, there you have it: new love.

One-Night Stand

Morton Feldman: “Samoa” (1968)

Initially, I thought of Aaron Copland’s “Hoe-Down” from “Rodeo” for this playlist, but then I decided that wouldn’t do; “Hoe-Down” would be too insistent that a one-night stand is a great adventure, à la “Johnny Guitar” starring Joan Crawford, or Charlie Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush.” I wanted something a lot more uncertain and stripped down to capture the emotions often accompanying a “no strings attached” affair. Feldman’s “Samoa” feels risky and unprocessed. It has a wandering quality, but it’s a controlled wandering: a rough, almost playful conversation among horn, cello, and vibraphone, interrupted by an otherworldly, hallucinatory piano motif. At the end, a sudden silence feels as irrevocable as a gunshot. It’s as if we’re being told, “All this? It’s not as casual as you think.” Nothing is insignificant.

BDSM

Maurice Ravel: Violin Sonata No. 2: II. Blues, Moderato (1927)

For the magazine Musical Digest, Ravel wrote, “The Blues in my sonata, par example, is stylized jazz, more French than American in character perhaps, but nevertheless influenced strongly by your so-called ‘popular music.’” He was describing his groundbreaking Violin Sonata No. 2, which was notable in its time for incorporating blues and jazz elements; Ravel had been inspired by W.C. Handy, whose music found an audience in 1920s Paris. The first movement (“Allegretto”) of this sonata emphasizes the stark contrast between piano and violin, abstaining from a tranquil blend of the two instruments. It’s ethereal and captivating. Nevertheless, the “Blues” movement, which I’m brazenly aligning with BDSM, is the sonata’s pinnacle. Like the “Allegretto,” it exploits the differences between violin and piano; however, here some “switching” occurs. The violin plays arco, as if “singing” the blues, then shifts to playing pizzicato, taking on the piano’s syncopated bass line. Near the end of the movement, the piano breaks free of ragtime-style chords and plays a bluesy melody of its own. This isn’t front-page kink, but it sounds like unfixed boundaries and feels like an exchange of power and control.

On-Again, Off-Again

Sergei Prokofiev: Sonata No. 3 in A Minor Op. 28 (1918)

This one-movement sonata, which Prokofiev adapted from notebooks he kept as a teenager, displays a range of energy and color. It begins at a frenzied pace, with a repetitive, leaping melody, then shifts into a ravishing lyrical section that could be a lullaby if not for the foreboding bass line. After that, the piece becomes an anxiety-ridden whirl of ascending and descending chromaticism and muddy bass chords. It’s the musical equivalent of one of J.M.W. Turner’s more tranquil seascapes (calm waters and golden sunlight) bookended by a few of Willem de Kooning’s more energetic and disquieting abstract urban landscapes. All of which is to say that Prokofiev’s sonata is a lot like a romantic relationship enduring a break-up and reconciliation before weathering a break-up yet again. If you think I’m full of shit, please tell this to the teen in your life who “isn’t interested” in classical music.

Ex-Love

Franz Liszt: Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major (1857)

Joan Didion famously wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” with the proviso that what we tell ourselves is phantasmagoria “we have learned to freeze.” This came to mind when I thought about “ex love” and what it takes to move on after a breakup. If what you tell yourself about an ex-lover is phantasmagoria, then you might consider changing the narrative and building your life out from there. Extending this idea to classical music, I offer Liszt, pioneer of thematic metamorphosis, who demonstrated the power of breaking free of “the original theme” (and allowing transformed themes to create lives of their own) in his Piano Concerto No. 2. The six sections of this work cohere through thematic transformations, about which Liszt “thought broadly.” As opposed to writing straightforward variations, he transformed themes into contrasting roles and created new structures out of the metamorphoses. So be like Liszt: embrace your volcanic love and suffering, but turn “the sickness of the soul” (Berlioz’s words) into something gratifying.

The Clink

Britta Byström: “Im Freien” (2020)

In a program note for “Im Freien” (German for “in the open”), Byström notes that “in det fria” is a Swedish expression meaning “outdoors,” but the literal meaning is “that one is in a free state, as opposed to imprisoned.” Byström conceived of “Im Freien” during the Covid-19 pandemic, when the world was in lockdown. She was thinking about captivity being indoors, and freedom being outdoors, and wanted to explore how a soloist could break free of constraints and “flow” above an orchestra. I imagine she was also thinking about Schubert’s lied “Im Freien,” set to a poem by Johann Gabriel Seidl. In Seidl’s poem, the speaker relishes a moment of relative freedom, in touch with nature and happy memories, before reuniting with a long lost “dear friend.” Prisons can of course be physical (the home you couldn’t leave during lockdown) as well as mental (your anxieties and delusions, a.k.a monkey mind). I’m sending forth Byström’s orchestral work as a counterweight to the prisons diminishing relationships and love itself.

Ultra-Romantic

Fryderyk Chopin: Impromptu in A-Flat Major, Op. 29 (1837)

Chopin’s Impromptu Op. 29 always puts me in the mind of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “Sonnet 43”: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.” I know our “poet of the piano” and English Romantic poetess move at different speeds; “Sonnet 43” requires unhurried reading and some pauses to grasp the full impact of the language. Still, my idea isn’t crazy. The speaker in Browning’s poem expresses immeasurable and everlasting love for a beloved, using anaphora within a formal rhyme scheme, and beneath the surface, “Sonnet 43” is bursting with feeling that accords with Chopin’s fevered, crystalline Impromptu (written less than ten years prior). Whereas Browning’s speaker proclaims “I love thee” at the start of successive lines, Chopin dazzles with exuberant, recurring triplet rhythms. Initially, Chopin’s rising and falling triplets sparkle like dew drops on new grass in spring. In the final section of the piece, when the triplets reprise their role then die away into silence, it’s as if nothing more can be said about the measure of love or a beloved. O to feel love so deeply, not merely as a bubbling fountain, but as a geyser.

Sentimental

Stefan Koncz: “A New Satiesfaction” (2018)

When I hear the word “sentimentality” applied to classical music, I think first of the many “new takes on old classics” on Spotify and Pandora. You know what I’m talking about: pieces like “Fullness of Wind,” Brian Eno’s reimagining of Pachelbel’s “Canon in D,” or “Recomposed,” Peter Gregson’s electro-pop-style modernization of Bach’s Cello Suites. “A New Satiesfaction,” a modern spin on Satie’s “Gymnopédie” No. 1, is another soft-centered confection. It contains a hint of sadness, but mostly it glimmers with sweetness and limpid passion. I don’t usually jump for treats of this kind, but I do love Koncz’s piece and hope you’ll let it melt in your mouth like ganache.

Life-Affirming

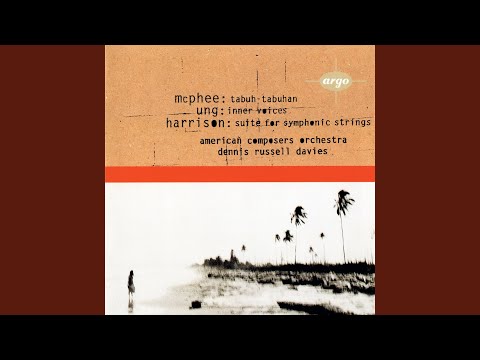

Lou Harrison: Suite for Symphonic Strings, 2: Chorale, “Et in Arcadia ego” (1961)

I listened to Harrison’s “Et in Arcadia ego” at least 20 times while reading Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian last summer. I don’t know exactly what Harrison had in mind when he named this movement from his “Suite for Symphonic Strings,” but no doubt he knew the literal translation of Et in Arcadia ego (Also in Paradise I am) and everything it signifies. In Blood Meridian, the Judge, who has been called “the most frightening figure in all of American literature,” carries a gun with this phrase inscribed in silver wire on the cheekpiece. McCarthy’s entire novel throbs with the idea that even in paradise, a state or place of indescribable beauty, Death is lurking. It’s dark, but this kind of death awareness can make you more responsive to life and whatever love—beauty—you’ve known. To that end, I offer Harrison’s “Et in Arcadia ego.” Conjuring exquisite beauty and the threat of that beauty’s abrupt demise, this piece is for those who are looking back or have lost love and reclaimed it. Maybe it’s also music for the eve of the end of the world. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.