Ours is the age of themes. Drowning in the deluge of streaming content whose rush, flow, and surge defines what Anna Kornbluh last year termed our too-late capitalism, any and all aspirant media—entertainment, art, or otherwise—is increasingly compliant with that dictatorial imperative handed down from marketing departments on high: brand or bust. Streamlined themes get things moving, help new media gain traction—even better if that theme can be rolled out into a packageable lifestyle. If brat summer’s hyperactive dissemination has proved anything to anyone, it’s just how quickly discrete media—an album, a font, a color—can be extrapolated for performative ethics and broadcast into a multifaceted global marketing campaign. Meanwhile, brand ambassadors and trend influencers push sponsored products that appeal to their “targeted demographic.” Pinterest board palettes (see Christian Girl Fall) and Starter Packs (like the Literary-It-Kid) guarantee unencumbered access to trendy personality-aesthetic bundles, all customized, linked, and sorted so you don’t have to! Hell, even insurance can be bundled. And all the while, social atomization and labor gigification are shifting the onus of sustainability and survival onto the isolated individual, encouraging each of us in turn to reframe our lifestyle according to delimiting and personalized thematics. Algorithms curate homespun “For You” pages, apps track patterns in our subconscious behavior, and at every turn we’re helpfully reminded what “Customers Who Bought This Also Liked.” You are your own best theme.

Classical music likes to parade itself as art outside the pale of such low fodder; this is a lie. Most everything it sells nowadays comes with themes already preinstalled: concerts, albums, seasons, festivals, anything that can be marketed announces itself with an angle, usually a pithy catchphrase heralding some universalizable ethos that, deftly applying to all the music on the bill, signifies nothing substantial. The Donaueschinger Musiktage is collecting this year’s concerts under the bromidic header alonetogether; the London Symphony Orchestra used brain-scan data from audience experiences to generate marketing content for their current season “Always Moving”; Detroit Opera just announced an extension of Yuval Sharon’s tenure, with three future season themes—America, Faith, and Sustainability—already teed up. This dictum of thematics is beginning to exert similar pressure on the very infrastructure of the field. Most symphonies now offer build-your-own “Subscriber Series” packages, ensuring listeners are never forced to hear music they don’t know or like. And on the production side, conservatories are facilitating near-ubiquitous entrepreneurship classes that teach students how to better market themselves as investment-worthy products for consumption in the modern gig economy. What is bought and sold today in classical music’s various economies are implicit senses of self: the (taste of the) customer is always right.

While marketing itself is no inherent evil—we are all inundated with advertising; legible previews help us more rapidly decipher where it is we want to invest our precious energy—this new over-reliance on themes across the arts has festered into an acute crisis of interpretive labor. As with Netflix’s 2013 cart-before-the-horse pivot from streaming platform to production house, thematic branding in advance of the performance decodes an interpretative map before a listener has had a chance to scope out the terrain on their own terms. It was once the prerogative of high school English classes to teach students how to spot class, sex, and death lurking within the basic plot points of The Great Gatsby—but only after they had finished the book. Themes were discovered through that slow, exhaustive labor of real-time experience and active interpretation. Now, they’re handed out upfront, allowing the listener to sit back, relax, and feel adequately smart, knowing that all they have to do is color within the well-established lines. But music suffers under passive, streamlined consumption, and when we impose interpretations, we risk losing music’s dialectical ability, unique among the arts, to speak of different things to different bodies in ever-different ways.

—which is what makes Time:Spans so special. The New York festival, this year in its ninth season, has rapidly established itself as an irreplaceable hotspot for contemporary music in an arts-weary midtown Manhattan. Every year in the sweat of August, stalwart city ensembles mingle with peers and composers from around the world to witness two weeks of unimpeachable music-making. Now permanently installed at Hudson Yards’s Dimenna Center, Time:Spans is a packed affair, a see-and-be-seen of musical royalty and scene regulars, but also of artists, writers, and other creatives from across the five boroughs. At a Time:Spans show, it’s hardly a surprise to find some wealthy art donor deep in post-show conversation with a gaggle of young composers, or spot a famous American novelist jotting notes during a JACK Quartet performance of Clara Iannotta. Time:Spans is good old-fashioned concertizing that way, delivering on the elusive promise of “something for everyone” without pandering to the universal accessibility that has watered down so much of the contemporary American scene. With its fidelity trained stolidly on aesthetic integrity and performance quality, it preserves a rigorous commitment to musical excellence increasingly difficult to procure in an immediacy-motivated economy.

Its ability to do so is owed almost entirely to a calculated remove from financial sway. Where most presenting organizations are beholden to the metrics and ideologies of their hosting institutions, sponsors, grants, or audience bases, Time:Spans—privately underwritten by the Earle Brown Music Foundation Charitable Trust that exists for the sole purpose of funding it—is free to make economically irresponsible choices in pure service of the art. The story of its conception goes like this: Earle Brown, one of a generation of iconoclast composers whose graphic scores defined a major outcropping in the New York musical avant-garde, had the good sense, as many experimental musicians do, to marry up. Susan Sollins, the legendary art curator behind Art21 and Brown’s second (and last) wife, took considerable interest and investment in her husband’s field, abetted by their significant disciplinary overlap (Brown, for instance, already had a Rauschenberg in his possession; the two were friends). After Brown’s death in 2002, Sollins continued to patronize new music’s many brambles, and shortly before her death suggested that a festival dedicated to contemporary music—not just to Brown’s, but to the field at large—would be a fitting tribute to their shared legacy and work. Sollins died in 2014, leaving behind an endowment large enough to secure the necessary resources in perpetuity. The following summer, Time:Spans—named for one of Brown’s orchestral works—began in earnest, spearheaded by Sollins’s sister Marybeth and Sollins’s hand-picked artistic director, Thomas Fichter.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Fichter is an odd find among more standard-fare alt-punk musical Brooklynites. In a culture presently fixated on celebrity curators (Mitsuko Uchida directed Ojai this year) and clout-generating artistic advisors (John Adams’s endowed “Creative Chair” at the L.A. Phil), the German transplant cuts an unassuming and perplexingly beige figure. From his muted business dress and mild, diplomatic manners, one would never guess that in his younger years Fichter toured on bass with Peter Erskine and Ensemble Modern before spearheading Cologne’s cutting-edge MusikFabrik into their boon years (the ensemble just announced his departure next year, ending 23 years of leadership). On appearance he is, at least by New York standards, just some guy. But boredom works in Fichter’s favor: without a cult of personality or brand identity to uphold, his festival is free to focus solely on the music, an ever-rarer quality in a scene overrun by gimmicks. He is, like the best curators, an inconspicuous hand: taking his work seriously and personally but without a hint of ego, he seems never to forget that he’s first and foremost a liaison. Time:Spans, year after year, gives New York the gift of putting good music first in no small part because Fichter puts himself last.

That’s not to say that he’s a pushover. Fichter holds two rules of thumb that hem his choosing. First, no intermissions, which he says allows programs to pack a more focused punch (and it does; the energy after his shows is unusually and consistently electric). And second, a near-total deference to music after 2000. Like any new music festival worth its salt, Time:Spans subsists on a heavy diet of premieres: Alex Mincek, Kate Soper, Igor Santos, Jonah Haven, and Klaus Lang all have new large-scale works getting first outings this summer. Plenty of others American works are being heard in New York for the first time. But equally representative are the number of U.S. premieres secured under his watch. This year alone will see recent works from the likes of Olga Neuwirth, Peter Evans, Jürg Frey, and Brigitta Muntendorf arriving to the States, as well as Steven Takasugi’s blistering “Piano Concerto”—which shocked audiences on the last night of Donaueschingen 2023—in a new chamber version. 24 years is a surprisingly long time, with quite a lot of music between. By giving himself a two decade-wide berth, Fichter ensures Time:Spans keeps a healthy dose of harder-to-come-by second or third performances and transatlantic rarities alongside the expected smattering of new.

Underpinning that commitment is Fichter’s coequal allegiance to the European heavyweights—both living and dead—whose sizable impact at best goes undervalued and at worst gets wholly forgotten in the American contemporary scene. The danger of the make it new imperative currently governing so much stateside grant rhetoric and curation is that the totemic works of modernity—the ones that build and rock the field’s foundations, and which take years of specialist dedication and significant institutional resources to pull off—get sidelined for a slurry of one-off chamber premieres. While certainly worthy of being mounted in their own right, an endless slew of small-scale newness evacuates room for the historical context necessary to pass informed judgement on aesthetics. By comparison, one can hardly imagine contemporary art collections like the Tate Modern or the Centre Pompidou without their permanent, adjacent displays of Bacon, Carrington, and Miró. Fichter continues to recognize that the resources of a festival make it one of the rare places where contemporary music’s pillar works—its “canon,” if there may be said to be one—can enjoy the performances and attention they deserve. The very first Time:Spans in 2015 closed with Talea Ensemble in what was at the time a rare U.S. performance of Hans Abrahamsen’s “Schnee.” Recent years have likewise seen huge works by Schoenberg, Lachenmann, Poppe, and Romitelli on the bill. And on the opening night of 2023, Fichter pulled out all the stops and shipped the entire electronics team out from Freiburg’s Experimental Studio to replicate Luigi Nono’s immensely technical late output, offering a one-of-a-kind evening of electroacoustic wizardry that will likely go unheard this side of the Atlantic for another quarter century at least.

Above and beyond these practical limitations, however, there is one last curatorial principle that Fichter unilaterally abides: “I refuse to have a theme,” he insists, “I just won’t do it. Instead I have… I guess you’d call them ulterior motives.” He explains: the things that typically guide his interests have little to do with an imagined audience experience (though he thinks about that too; Fichter has excellent and wide-reaching taste). Rather than serving its own aesthetic ends, Fichter treats the festival as an important cog in a multi-national ecosystem of composition and performance.

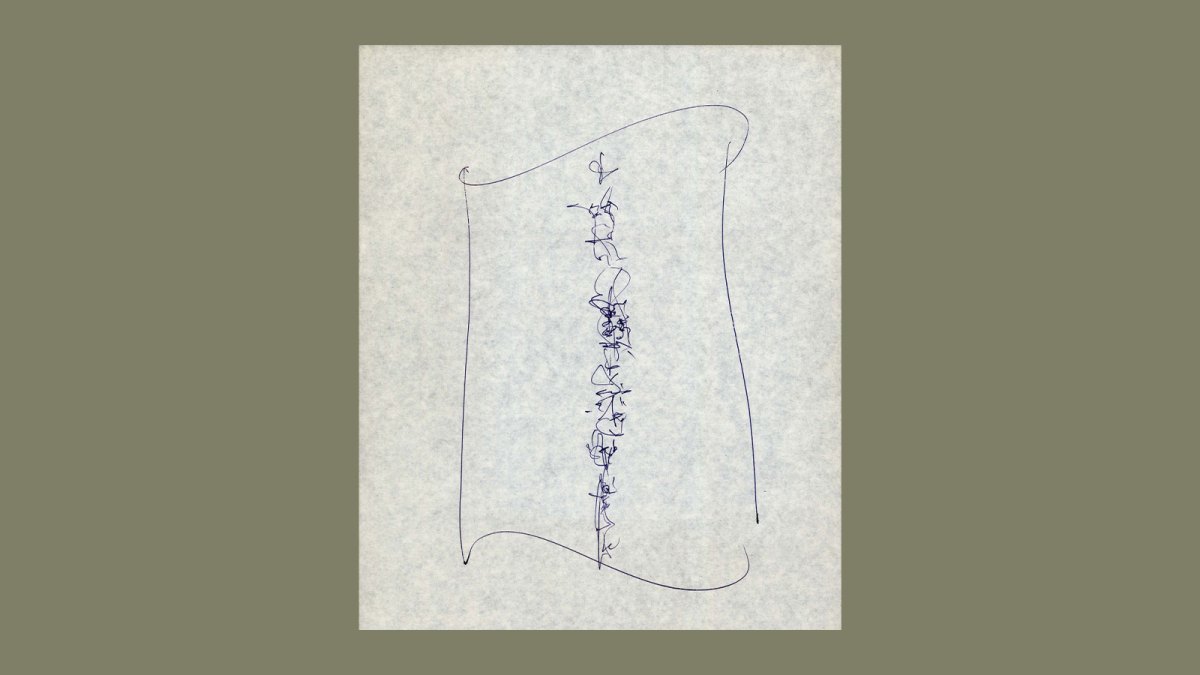

“I’m interested in networks, streams, things that I can bring together,” he confides. “It’s really like a fungus model or a brain system, with all these different roots or underground connections. Each of the concerts is like a different location, except they’re all connected by some sort of underground system that’s both everywhere and not, decentralized but unified. I’m not creating a concert or 12 concerts…I’m living in a node inside a system, and trying to show all the ways it is connected to other things.”

What that means for programming is that the work-performer connections often take place in subliminal sociological registers unimportant to the momentary musical experience. Take Fichter’s Nono program. With the composer’s centennial in 2024, it would have made far more thematic sense to delay that concert until now. But doing so would have willingly played into a zeitgeist by programming a portrait only when a major anniversary called for one. Instead, Fichter quietly admits he’d done it a year ahead of schedule in the hopes that selling out late Nono would signal to other, richer organizations that the Italian composer’s major output—he mentions Nono’s last opera “Prometeo” specifically—might be successfully mounted in New York City limits. The Time:Spans concert was thus in one swing an international collaboration (the American conductor Brad Lubman leading a multi-national collection of players in consort with a specialist German production team, all playing Italian music); a rare American homage to one of the great European voices of 20th-century composition; and an attempt to secure better institutional credit for Nono in advance of his birthday. Fichter puts no purchase in the temporary satisfaction of self-evident or localized thematics. Instead, he keeps his sights trained on the bigger, slower motions actively shaping our cross-cultural artistic ecosystem. (It almost goes without saying that those valiant dreams were futile. No plans for such a staging ever emerged—a reminder that, despite Fichter’s considerable influence, American programming still has far to go.)

Similarly, Fichter points to two nights in this year’s festival—one by Alarm Will Sound, the other by Talea—that he thinks highlight the fruitful possibility of such rhizomatic programming. Knowing as he does that the American ensemble economy is fueled by exhaustive residency work with young composers—work that rarely enjoys repeat performances or large-scale celebration—Fichter invited both groups to curate a collection of favorite collaborations from their last decade of teaching. Alarm Will Sound prioritized their years in residence at the Mizzou International Composers Festival in Missouri, while Talea drew from all over, and both showed up with electric mixes of brand new works unified not, as in a usual program, by some arbitrary poetic image (or worse, shared nationality or gender), but by the collaborative ethics underpinning the ensemble for whom they were first written. The intention, Fichter explains, was to give space for emerging composers to enjoy repeat performances of their work in New York while simultaneously highlighting the active role traveling ensembles play in shaping young compositional development across the country. And by allowing both ensembles to curate their respective nights, the festival keeps performers engaged in the real work of American new music, finding in the often-mindless labor of “student pieces” those hidden gems that deserve to be more widely heard.

It’s not all that uncommon for Fichter to be so hands-off with the piece-to-piece details of a program. “The other fundamental principle I work with is motivation,” he says. “I have antennae out for intentions. If the motivation is just money—I want to be paid to play—it’s completely against our principles. It’s just not artistic.” To that end, Fichter avoids the “assignment model”—I pick the repertoire and tell you what to learn—at all costs, preferring to let ensembles and soloists pitch their own ideal nights. As he explains all this, he gets serious and shakes his head. He receives an impossible number of unsolicited proposals a year, he admits, many of which are poorly-veiled hopes for adding Time:Spans to a résumé. These, he says, make him dispirited, because they miss the festival’s whole point.

“I’d rather invite people to discover something about their own ensemble or to fall in love with composers they’ve never heard before, to create relationships which are very meaningful, you know?” he says. “I like the projects that are motivated by art and by a deep feeling of commitment, not just by the money.”

Fichter has built many of these bridges by hand. Year after year, he goes to bat for a cadre of younger composers widely admired in European circuits but routinely overlooked in the U.S. on the “aesthetically difficult” grounds. Clara Iannotta, Sabrina Schoeder, Mark Barden, Cassandra Miller, Kelley Sheehan, Sivan Cohen-Elias, Stefan Prins, and Catherine Lamb have all been featured on past or current seasons; not, as is usually the case, in performances by their associated European ensembles, but in top-notch interpretations by equally qualified Americans—equally qualified Americans who now have that music in the repertoire. These are Fichter’s bridges. His point is not to “Euro-fy” the American scene—though at a time when the French are doing “Nixon in China” and the Germans are rebuilding Dlugoszewski’s instrumentarium from scratch, a bit of this is probably due as well—but to suture, night by night, the fragile diplomatic relations between nations, styles, and ideas. He does it not because diverse programming looks good on paper, but because we should all of us—performer, listener, or otherwise—have the chance to hear good music played live by people who love it. There is no higher order of artistic experience.

And like any good diplomat, he knows to keep all things in international equipoise. This year, Canada’s Bozzini Quartet is taking two back-to-back evenings. First, in a portrait concert of the Austrian Klaus Lang, with the composer (an accomplished organist) riding sidecar on harmonium; and then a portrait of the Swiss Jürg Frey, this time in conjunction with saxophone quartet Konus. Neither composer gets significant airtime in North America, much less whole evening portraits: both of their musics are the glacial, patient kind that runs counter to sound-byte-motivated American eclecticism. But later in the festival, New York’s favorite JACK Quartet will return Timothy McCormack’s “your body is a volume” to the stage. The American composer rarely gets performances at home for similar aesthetic reasons, but the hour-long marathon of harrowingly slow hermeticism, written for the JACKs seven years ago, is a testament to the productive state of equally beautiful, difficult music and its interpreters being grown “in-house.” Even there, though, ulterior motives for communal good are actively at play: the concert is an unspoken launch for their Kairos recording of the work, slated for release next year. True to form, Fichter is always two steps ahead.

Postlude

Wrapped up in our 21st-century addiction to curated thematics is yet another iteration of classical music’s enduring crisis of social validity. Art music, which promises no financial return and contains no self-congratulatory political messaging, faces an uphill battle to justify its existence in a culture accustomed to the guarantee of “love it or return it free of charge.” We lately feel the need to hitch our cart to some or another social trend as a handy affirmation to any doubtful outsider that this weird art is a necessary contribution to humanity. Unless music can be ventriloquized to say something specific and diagnosable about topical society, we seem to ask, can it be said to be worth anyone’s time or investment? New music is especially susceptible to this too-late-capitalist anxiety. Already weakened by the defunding of local arts by international governments, devaluations in the academic humanities, shortening attention spans in post-MP3 music consumption, and an anti-intellectual bent in modern politics that would correspond difficult aesthetics with elitism, we instinctively knit themes to yoke our confusing progressivism with more “accessible” social agendas in a concerted effort to merely survive another year. This imported accreditation permits a performed participation in the identity markets of late capitalist economies, but it does real damage to the art itself, which is systematically disavowed of its ability to think and speak for itself. Thematic aestheticization = artistic anesthetization.

When, however, we dig our heels in the sand and refuse the call to make art participatory in economies of circulation—and by so doing, relinquish our dependence on the preinstalled interpretive promise of marketing’s packageable thematics—we return some real power to the music. At a time when mass culture would package every slice of media it can get its dirty hands on, Time:Spans is our annual reminder that to be rigorously anti-thematic—and uncategorizable, omnivorous, and promiscuous besides—is a more provocative affirmation of experimental music’s communal political thrust than any kitschy brand or phrase could ever be. ¶

Update, 8/16/2024: A previous version of this article identified Marybeth Sollins as Susan Sollins’s daughter. They are sisters. VAN regrets the error.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.