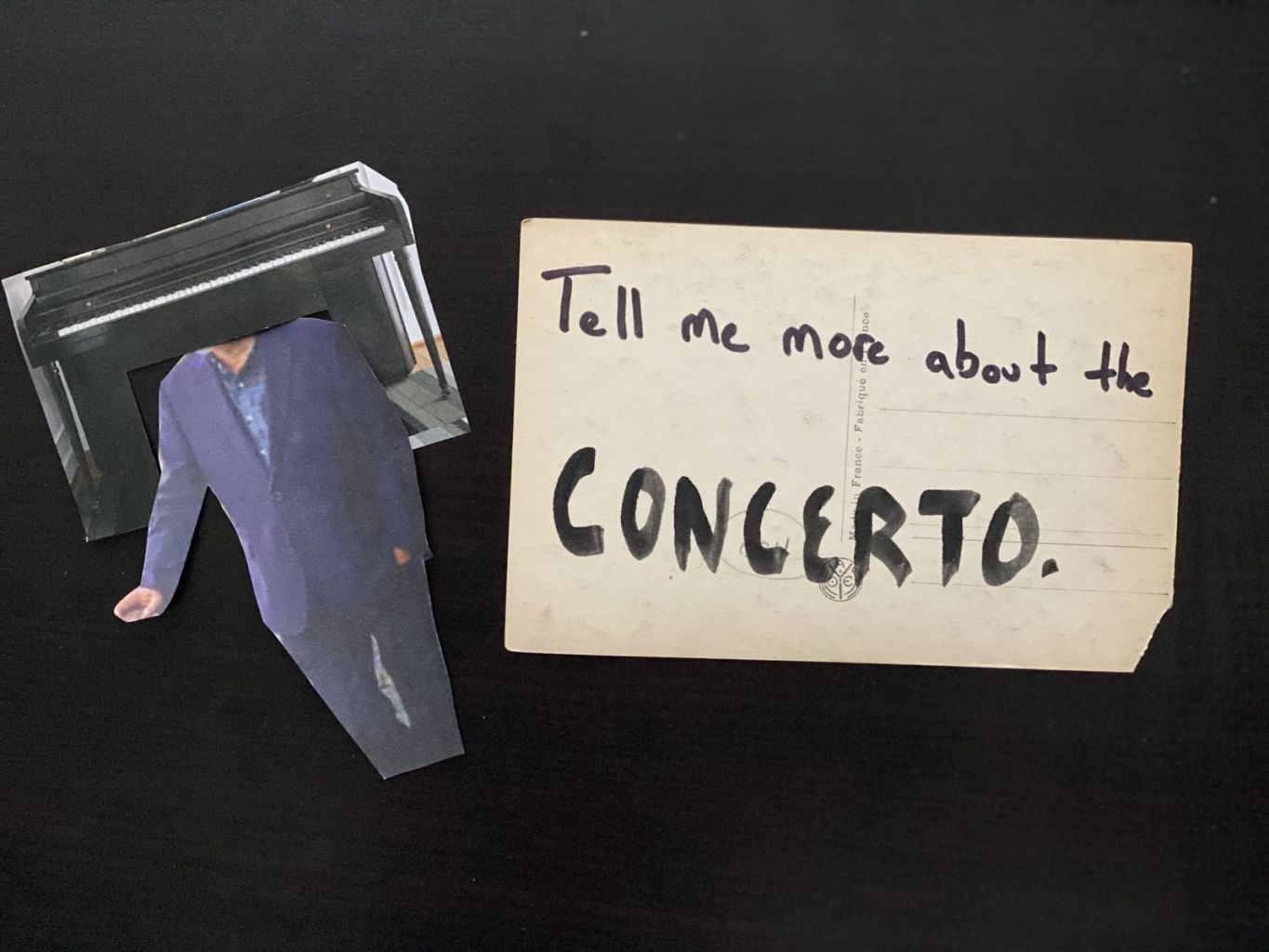

Steven Takasugi’s Piano Concerto will be premiered by Roger Admiral, Ingo Metzmacher, and the SWR Symphonieorchester in collaboration with the SWR Experimentalstudio on October 22. It will be the final work of the 2023 Donaueschingen Music Days, a festival for contemporary music in southwestern Germany. The following texts were extracted from an interview held at Takasugi’s home in Newton, Massachusetts on September 29. Steve left for Stuttgart the following day to begin rehearsals. The postcards followed.

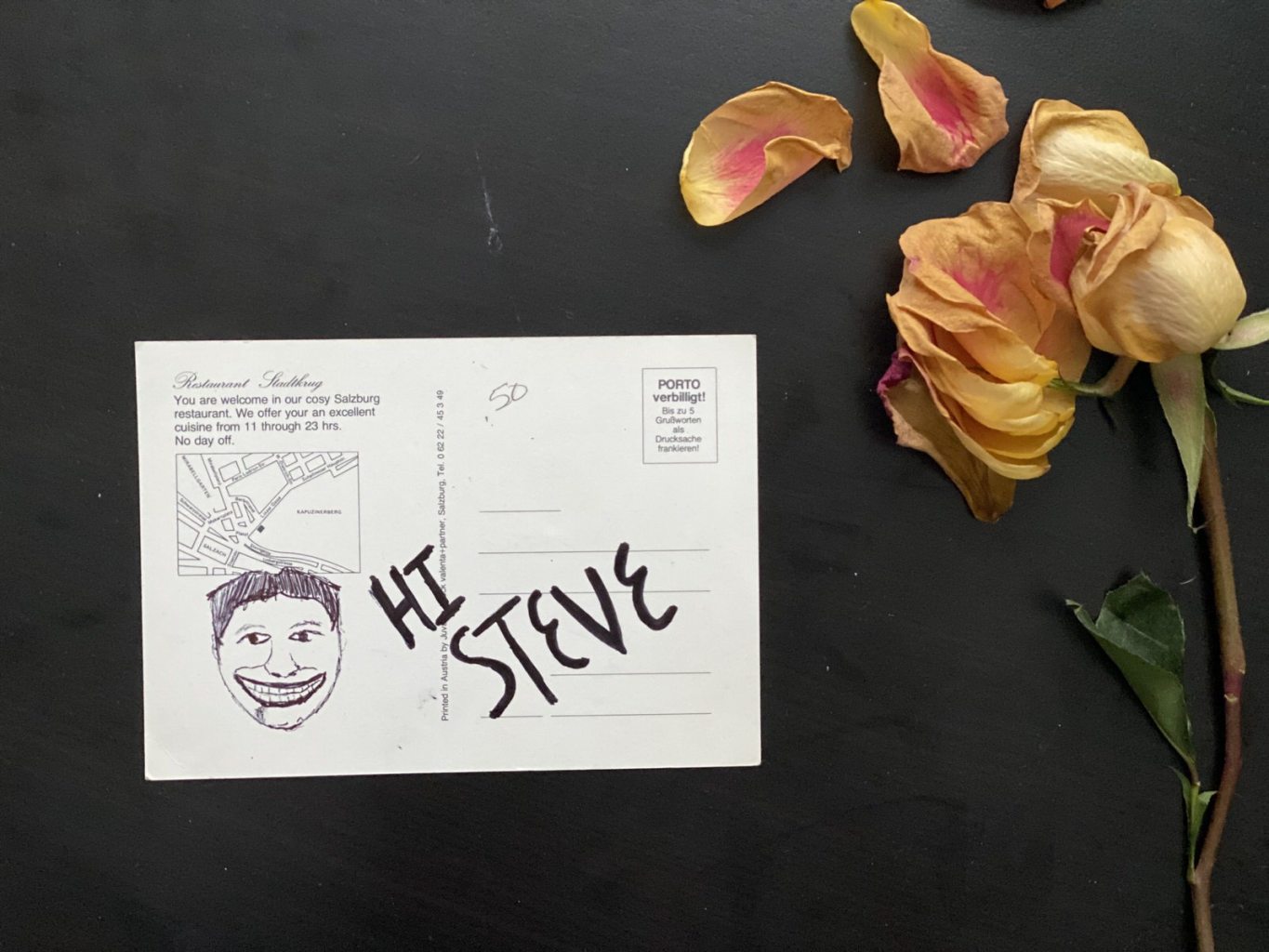

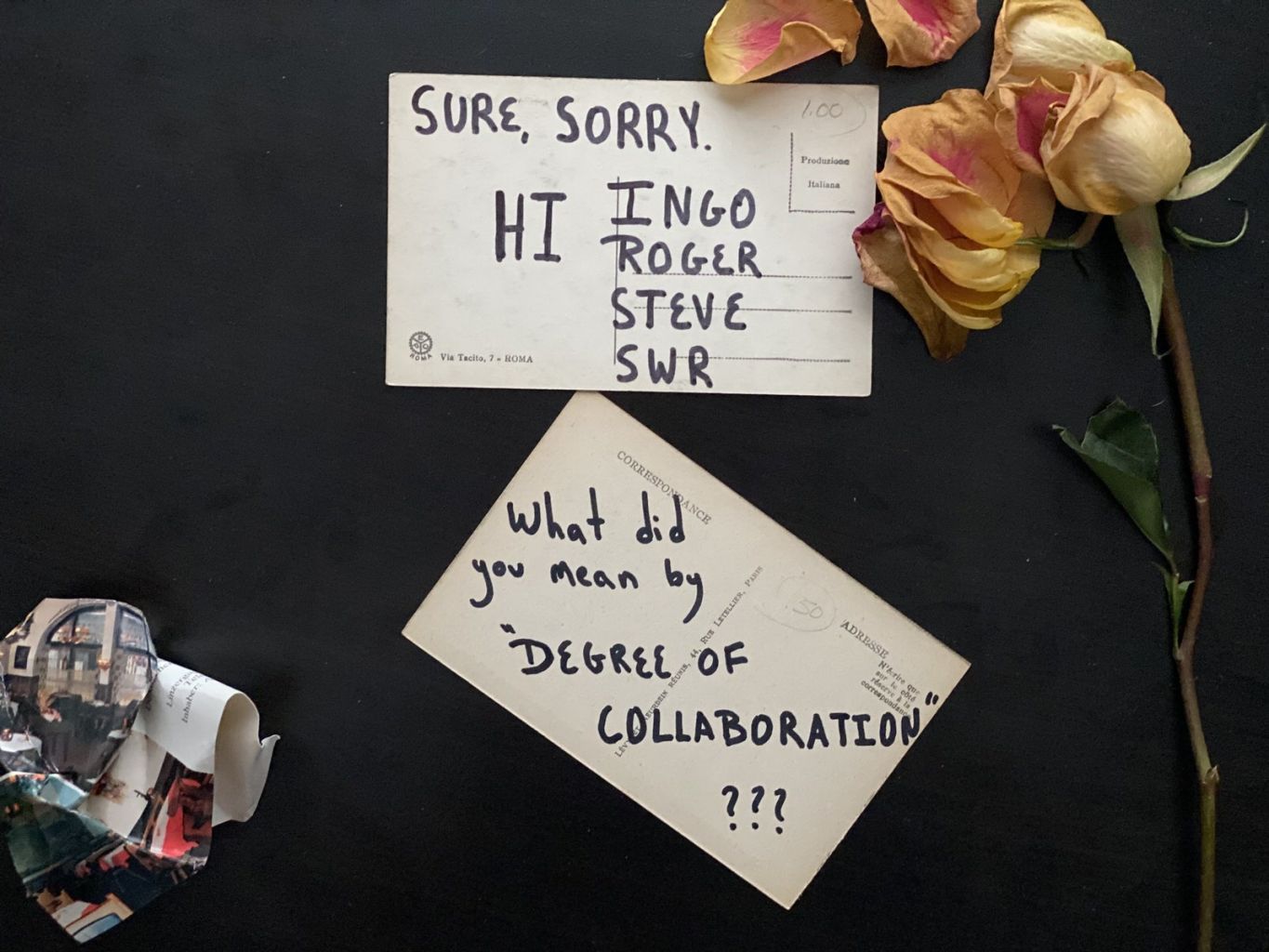

Steven Takasugi: Sorry, but shouldn’t the musician’s names be on the cover of the piece too? The ritual that you have this big name is just a convention. I think their names should be on there, in equal size, in alphabetical order, especially when you reach a certain degree of collaboration. I often threaten to break that convention. I wouldn’t mind that.

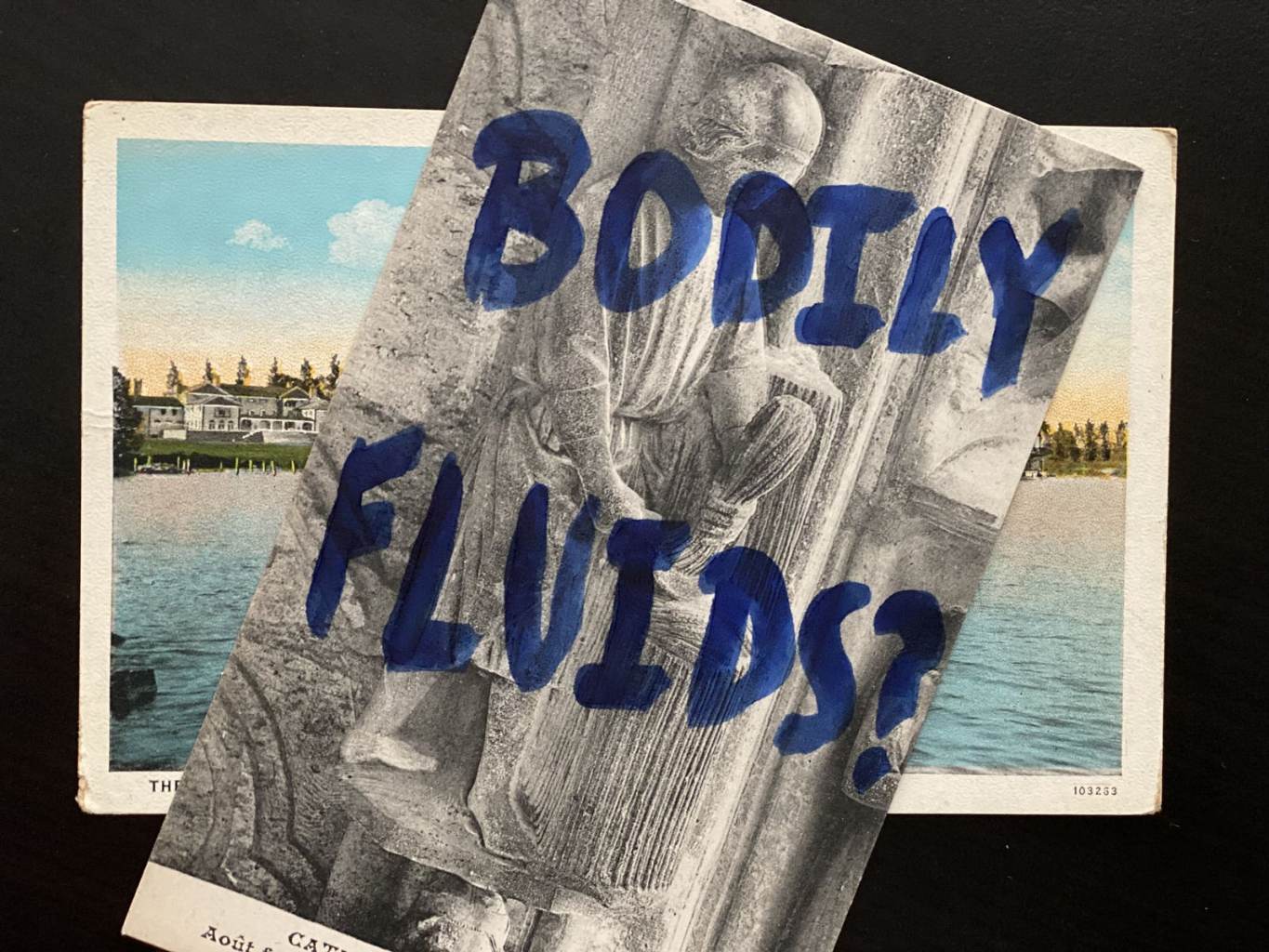

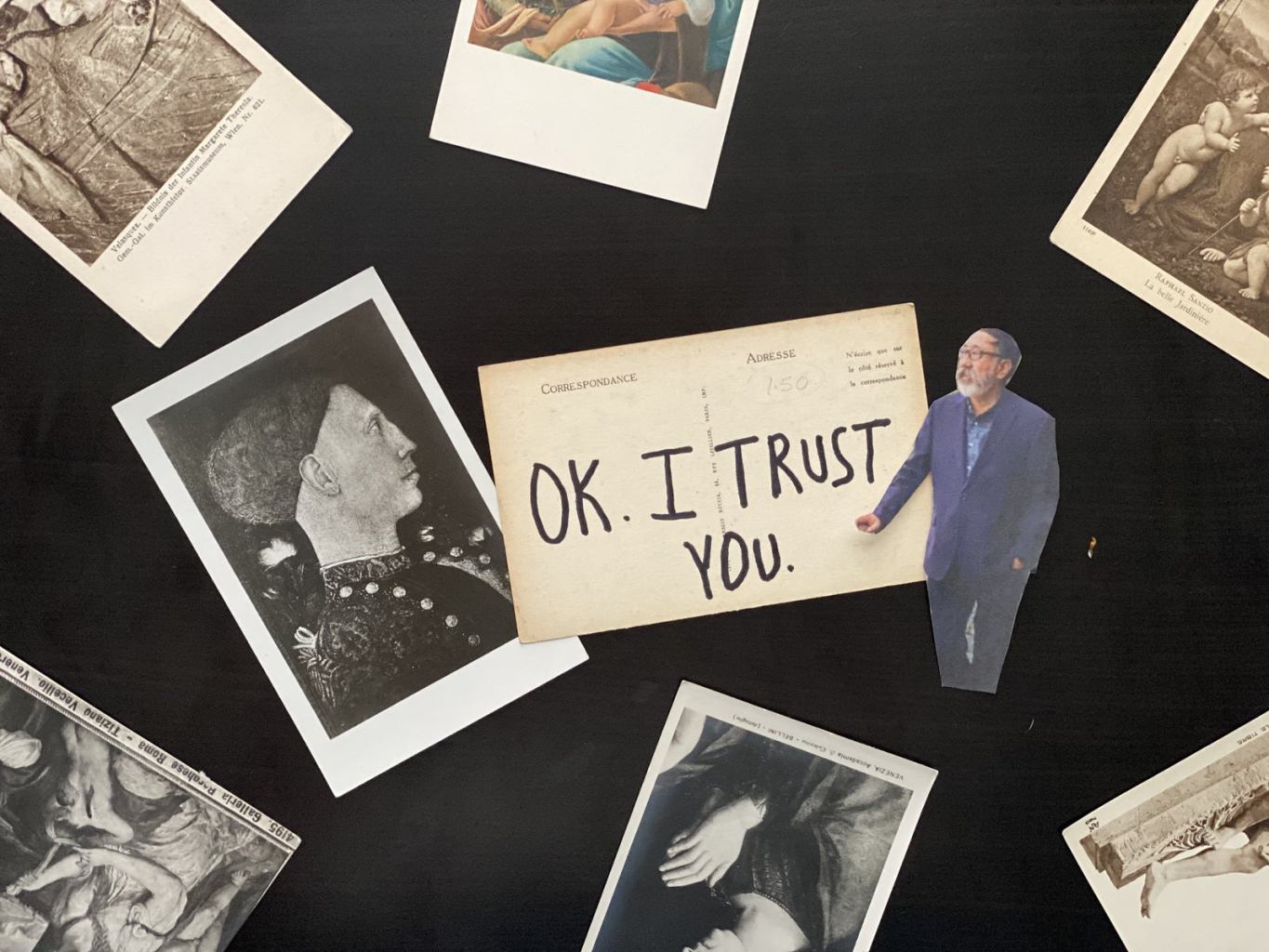

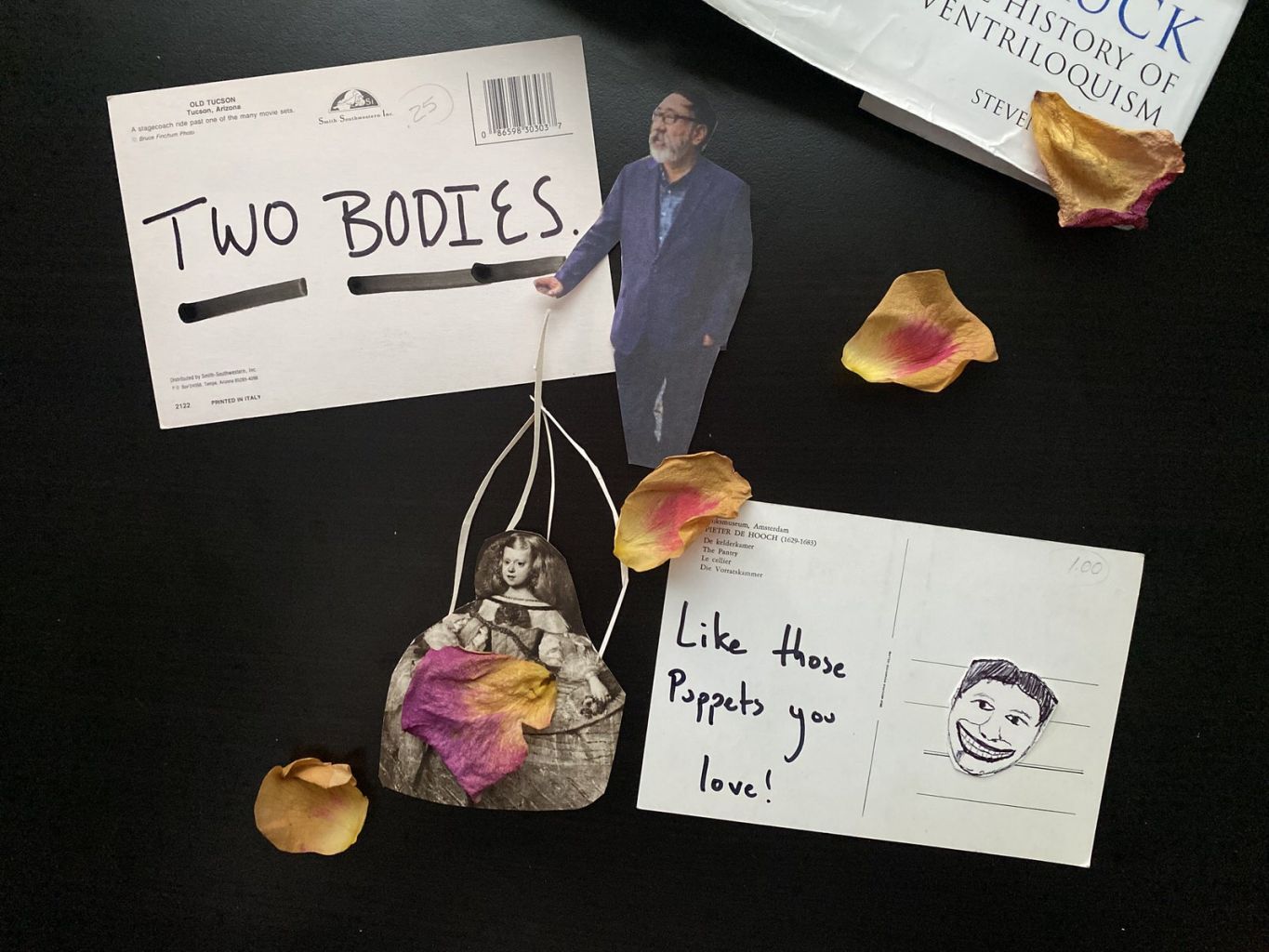

Well, when I say that we’re collaborating on a work, everyone assumes that the composer is rationalizing certain decisions about what’s going to happen in time. But there’s also the piece itself. The piece has a body. There’s not just this duality going on of performer-composer; there’s also this work that has its own authority. It’s saying: “I need this,” and the composer might not know what “this” is, and the musician doesn’t know yet either, or maybe does—it’s a negotiation. And then the musicians bring their bodies, very literally, into the picture, and that’s another thing speaking. When all that happens, it’s the best part of the music, because there are incongruities and tension. That’s when everything emerges; that’s when bodily fluids come out!

Well, I started out writing tape music and I did that for 20 years. And then, in 2003, I was confronted with an opportunity to bring live players back into the equation—that was a piece called “Strange Autumn.” Then I went back to writing tape music. But after a bit I realized I wanted the people to return permanently, and when they did it was really fascinating. I mean, in some ways it didn’t work and in some ways it totally worked. It was even better than what I had before, because it had sweat and spit and smell and human necessity—bodily fluids. It created a kind of three-dimensionality for my work. And now I can’t imagine not having the live performers in the equation.

That said, I didn’t start out thinking, “Now I want to deal with bodily fluids.” Bodily fluids were an artifact from the whole process. I just got into rehearsals and they were there! But the awareness of bodily fluids in my work came from a realization I had about “Sideshow.”

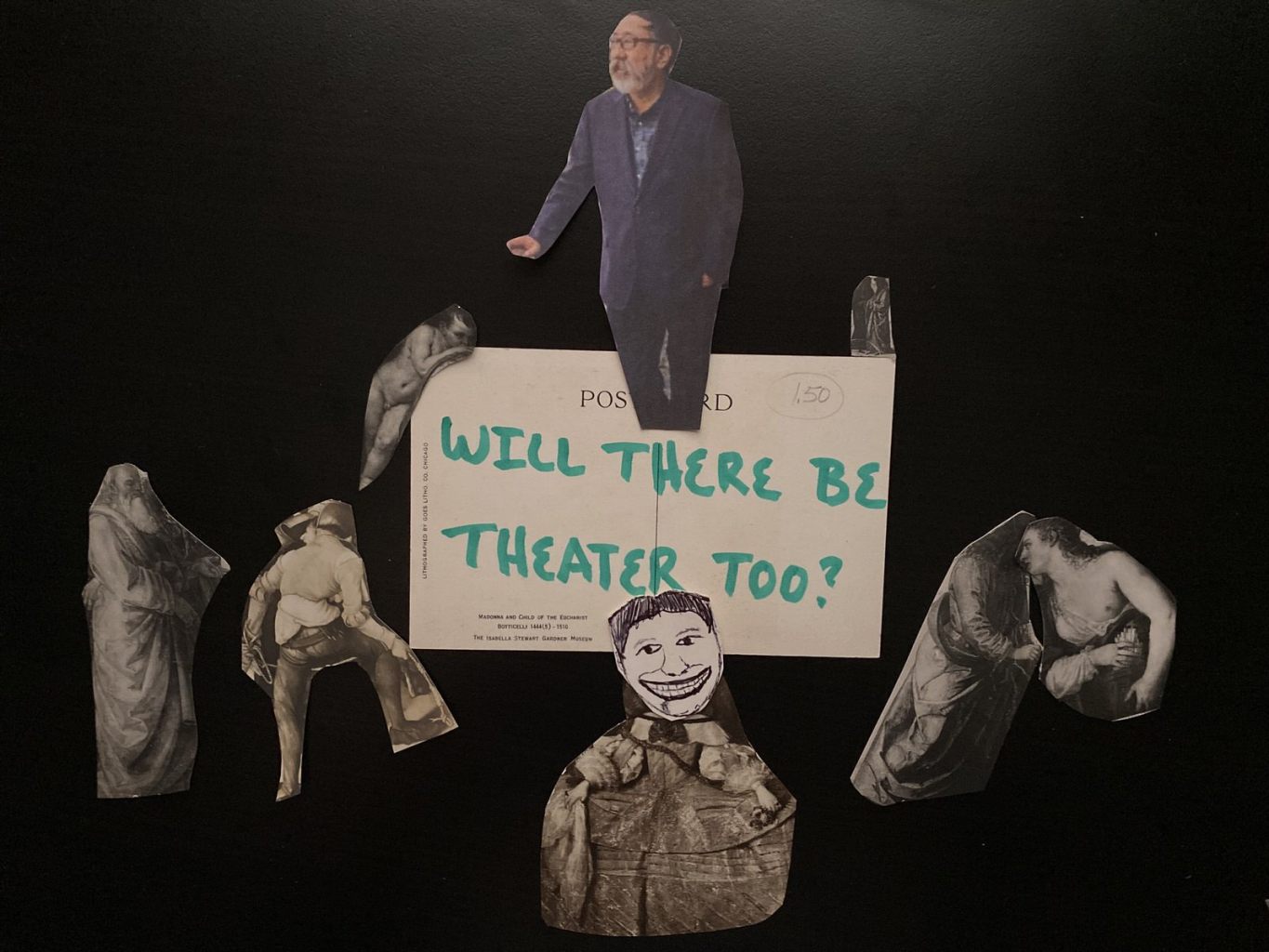

Takasugi’s “Sideshow,” for eight performers and electronics, has become an icon of modern music theater. Riffing on aphorisms by Karl Kraus, the piece draws parallels between the mechanical grotesqueries of New York’s Coney Island and early 20th century Viennese Expressionist art. The players sit frozen with uncanny smiles, glitching and overly animated, sometimes miming, sometimes playing, sometimes lip-syncing, sometimes breaking; the electronics blur the lines between what is seen and what is heard. It creates profound confusion for the viewer, who can no longer tell what’s what. This, Takasugi says, is when the “uninvited guests”—the ghostly second presences of invisible usurpers who claim sounds they don’t produce–slip in.

There’s a video of the piece, and it kind of works, but it’s still really just a document. When I show it, I’m always apologizing that you’re not there for the live performance, because you need to see “Sideshow” live. Especially if you sit in the front row, it’s very intense. The performers are doing a lot of “p” sounds and vocalizations where they’re spitting. So you might get bodily fluids on you! A splash zone.

And Alex Lipowski, the percussionist, is not allowed to close his mouth in certain sections, but he’s still doing a lot of vocalizations which means he can’t swallow his spit. It gets caught, and it starts dripping. Now, when other performers do this part I tell them: ”You can’t swallow your spit.”

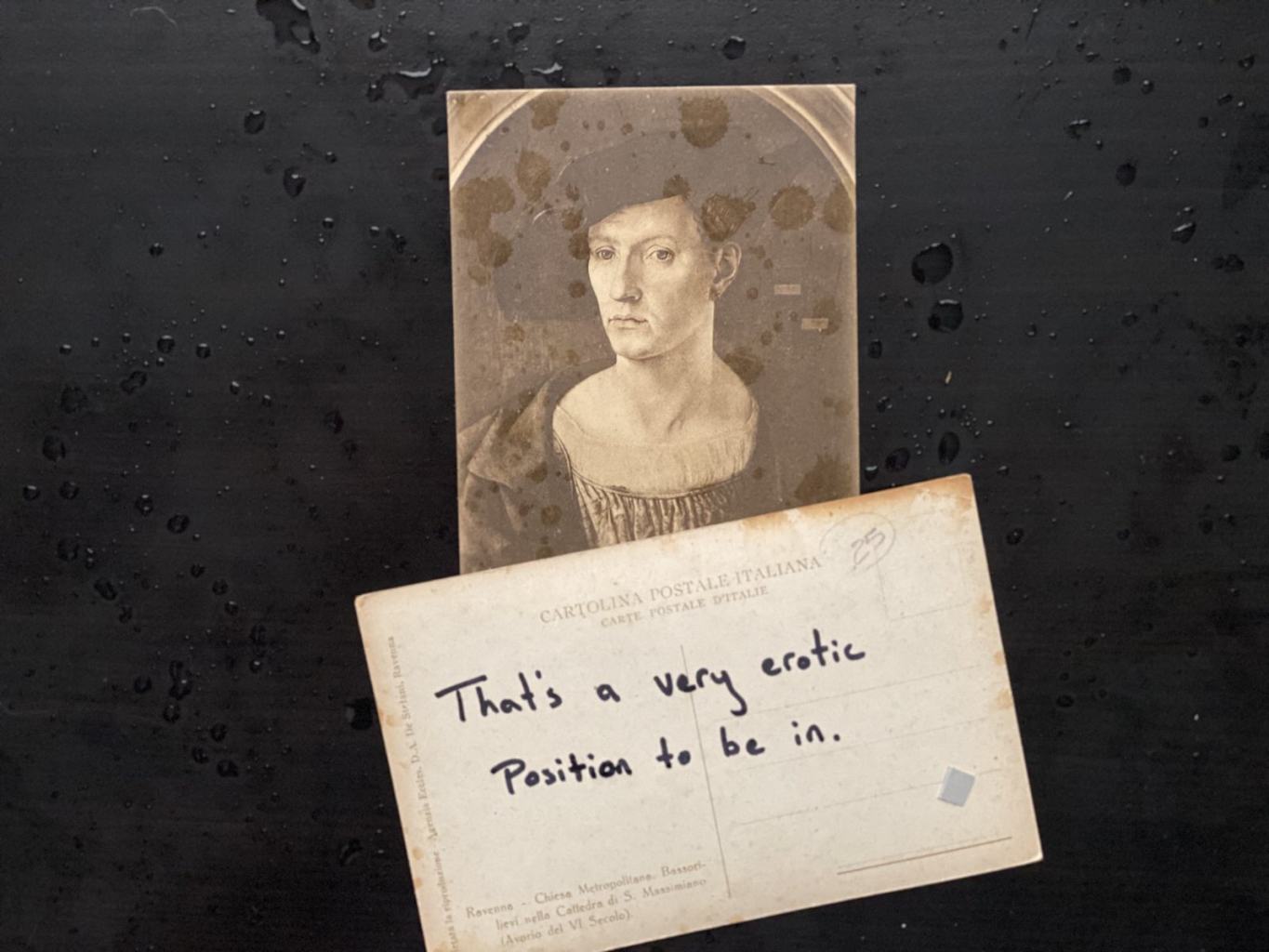

That eroticism is a really important component when you bring in live people. So is protest, actually, which also comes from power and tension. I think protest and complaint belong with sweat and spit.

For example, in the Piano Concerto, the orchestra stays frozen in the movement breaks. They’re all keeping the tension that would otherwise be natural relaxation. And I don’t know if that’s going to work! Because that means that they’re holding their arm up for half an hour, and they’re going to start screaming at me: “When are we going to rest?” But when I’m writing, I don’t think: “They’ve been holding their arm up for a half an hour.” For me that’s a conceptual thing, it’s their problem! PROUDGIGGLE And if they want to rebel against the directions, or non-directions, they’ll tell me. They’ll get huffy and puffy, and that will be interesting, because it’ll add tension to the kind of rapport I have with them. But I think sometimes it backfires, because when they get to protest a little bit to the composer, it gives them an added sense of… I don’t know… being able to claim the piece for their own and make decisions about it.

I realize they might also think I’m a dilettante, that’s the other side of the coin. Like, “Don’t you realize we have to rest our arms?” And I’ll say “Conceptually, you shouldn’t have to!” MISCHIEVOUSGIGGLEGIGGLE “So let’s solve this. Let’s see what we can do to maintain the tension. I mean, what about speed? Maybe you’ll come into resting position very slowly? Or maybe a number of you will do it and then you’ll take turns?” We can figure those things out.

I always knew I’d write a piano concerto. I mean, I’m a pianist, and I just play piano concerti. Isn’t that weird? Without any orchestra. You can’t play it for people because there are these gaps. It’s not a proper recital piece, and I like that because it’s kind of weird.

I wrote the first movement—I think it’s around 15 minutes—for the LA Phil. I was asked to write a piece for them while I was writing the piano concerto, and I thought, “This is a great opportunity also for my Concerto. I can learn a lot about orchestration.” I did learn so much.

In that work, I had theater for the orchestra: They stood up, they did strange things, they had to act. It was fun! But with the LA Phil you get three very short—one hour maybe—rehearsals, so there isn’t really time to work on such details. You have to accept that because the budget for one minute… it’s like a hundred people!

In the Piano Concerto, the theater is what I call “subtle theater.” Suddenly I’m saying, “I don’t only do this in your face! Sorry folks!” GIGGLEGIGGLE I know that you might expect it, that there might be some grotesque grinning or something, but I also don’t want to be typecast as that composer.

That being said, there is that idea—always in my work—that when you’re pausing you freeze. In that sense there should be a kind of look and visual experience as well as auditory. We’ll see what they do with the freezing; it’s hard for me to give up on that.

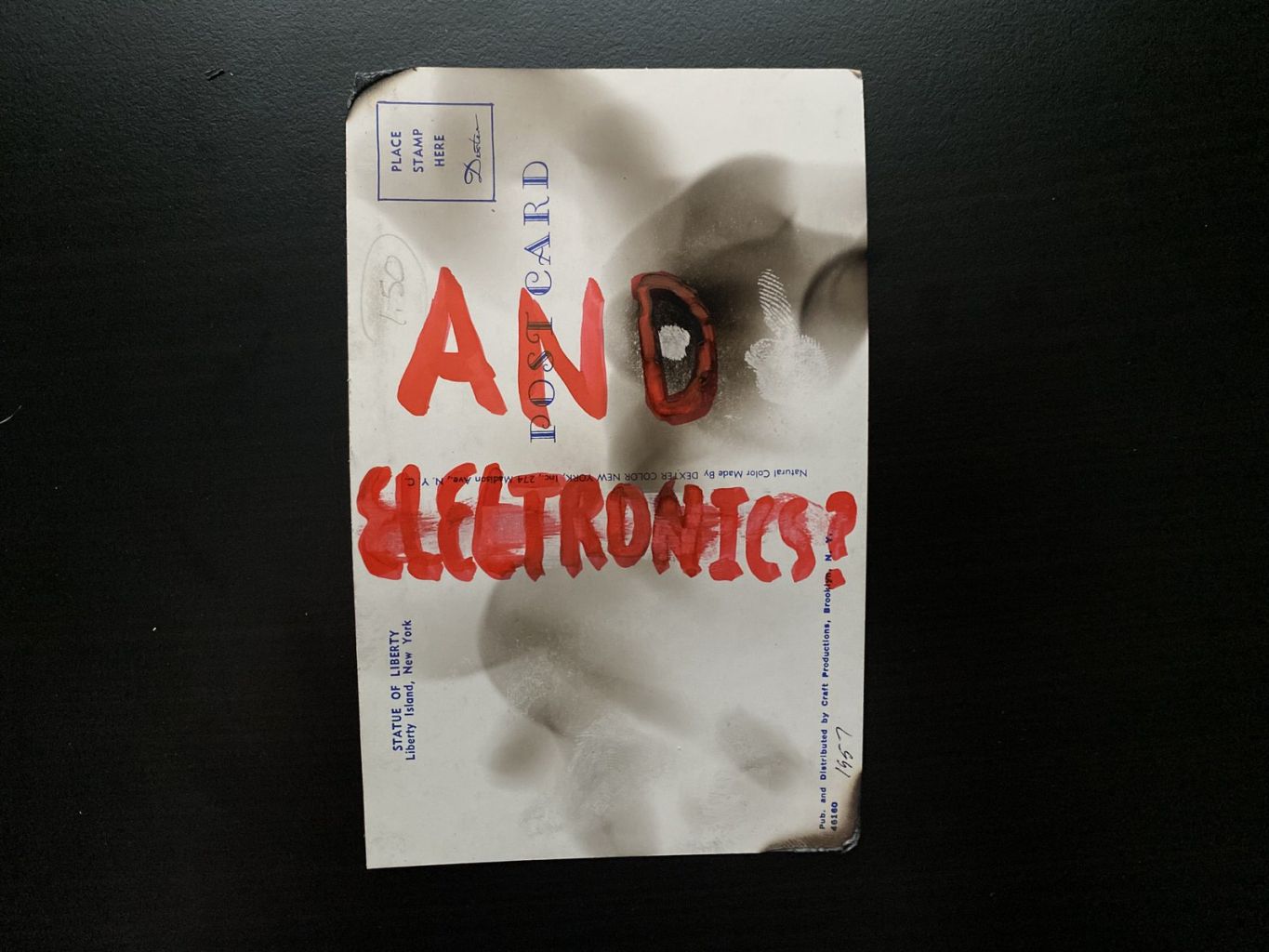

Electronics are a cantus firmus for my work, they allow me to get that precision. It’s really the canvas on which I work. It’s often a kind of stand-alone.

Ventriloquism, doppelgängers, that all arises from having the tape piece underneath it. There’s a notion of translation going on, which is very problematic because it seems to be saying, “The real music is the tape music, and on top of that we’ll put musicians, but they’re not absolutely necessary, they’re actually being controlled by the authority I have that’s underneath them.” But that’s just an assumption! Because when the music comes alive with live performers, it’s no longer that at all. They claim the piece, and they steal it! GIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLE!!!!!

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Protest. But the way they do that is an interesting thing. If they aren’t allowed to be exactly musicians, then they’re doppelgängers, they’re ventriloquists, there’s a sleight of hand going on: You don’t know who’s playing! PLAYFULGIGGLE You enter this house of mirrors, and I love this idea because that’s when the confusion takes place: When you don’t know who’s actually eliciting the sounds. Sometimes they’re lip-syncing, sometimes they’re not, it gets to a point when you’re in such a house of mirrors that even the musicians—even me—don’t know exactly what’s going on. The musicians might think their partner is playing live, but it’s actually on the playback. And then they discover: “Wait a second, that’s not you doing that? I thought you were always doing that live!”

It can also go the other way. The saxophonist Philipp Stäudlin asked me a question once, he said: “According to the score I’m supposed to be lip-syncing, but on the playback there’s nothing there.” And I thought “…whoops! Oh, yeah, I guess that’s a possibility isn’t it!” AMAZEDGIGGLEGIGGLE It’s such a house of mirrors that you’ve been told you need to lip-sync something, but actually there’s nothing there. It’s a reflection of a reflection: it’s an illusion.

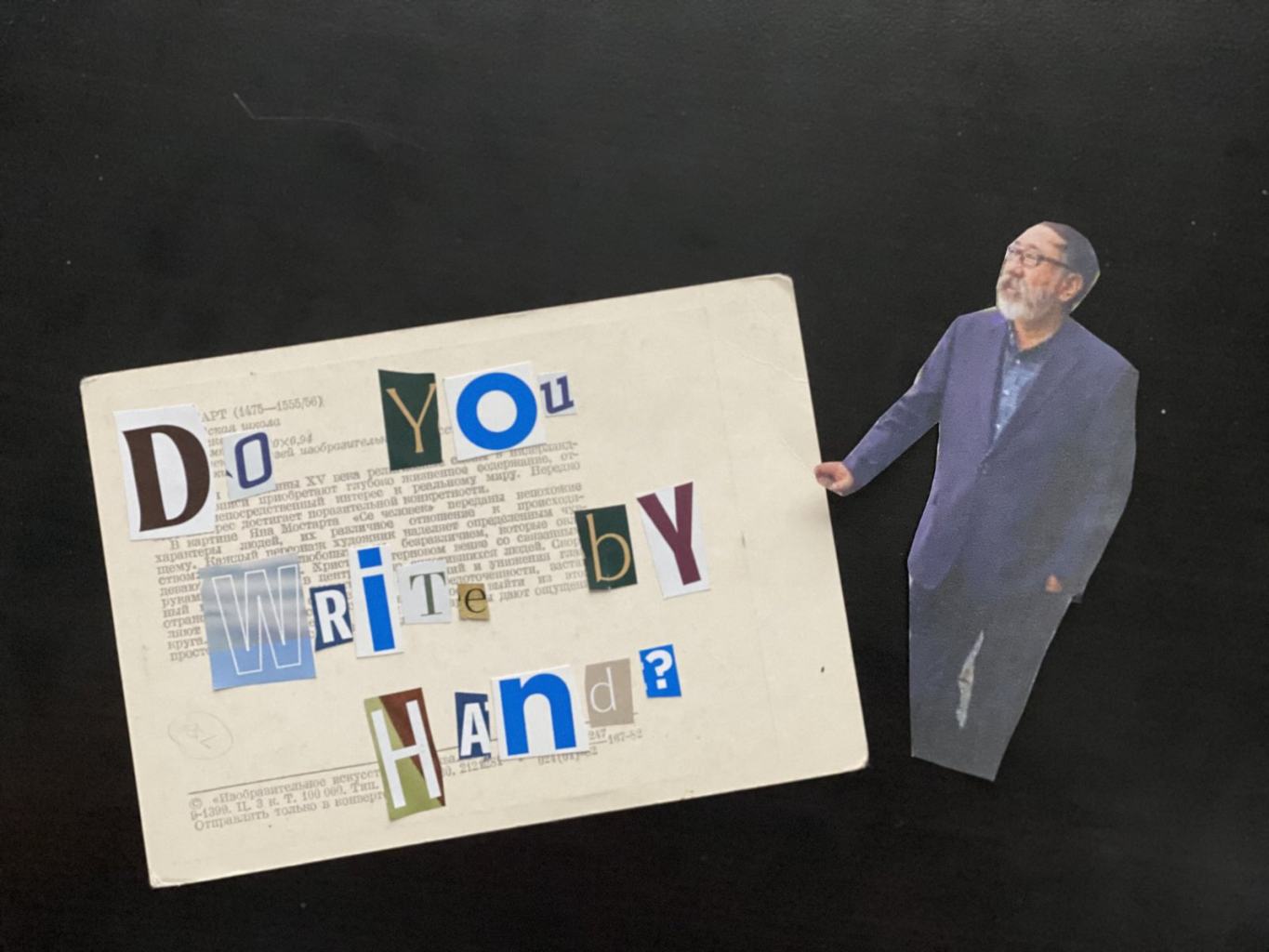

Oh no, I don’t do hand. When I was a graduate student, everything was done by hand. I studied with Morton Feldman, and he composed at the piano. He’d play MIMES PLAYING and then he’d write his notes. MIMES SCRIBBLING All of that was there in my development. So now, when I go to the piano, I immediately have my fingers in the position HANDS OUT and it’s usually a very beautiful Feldman-esque chord! GUILTYGIGGLE I even think that to some degree, if I were to write a score, his notational style would be there too in the handwriting. So in order to get away from Morty and to become what I needed to become, it was really important that I not go to the piano or write by hand.

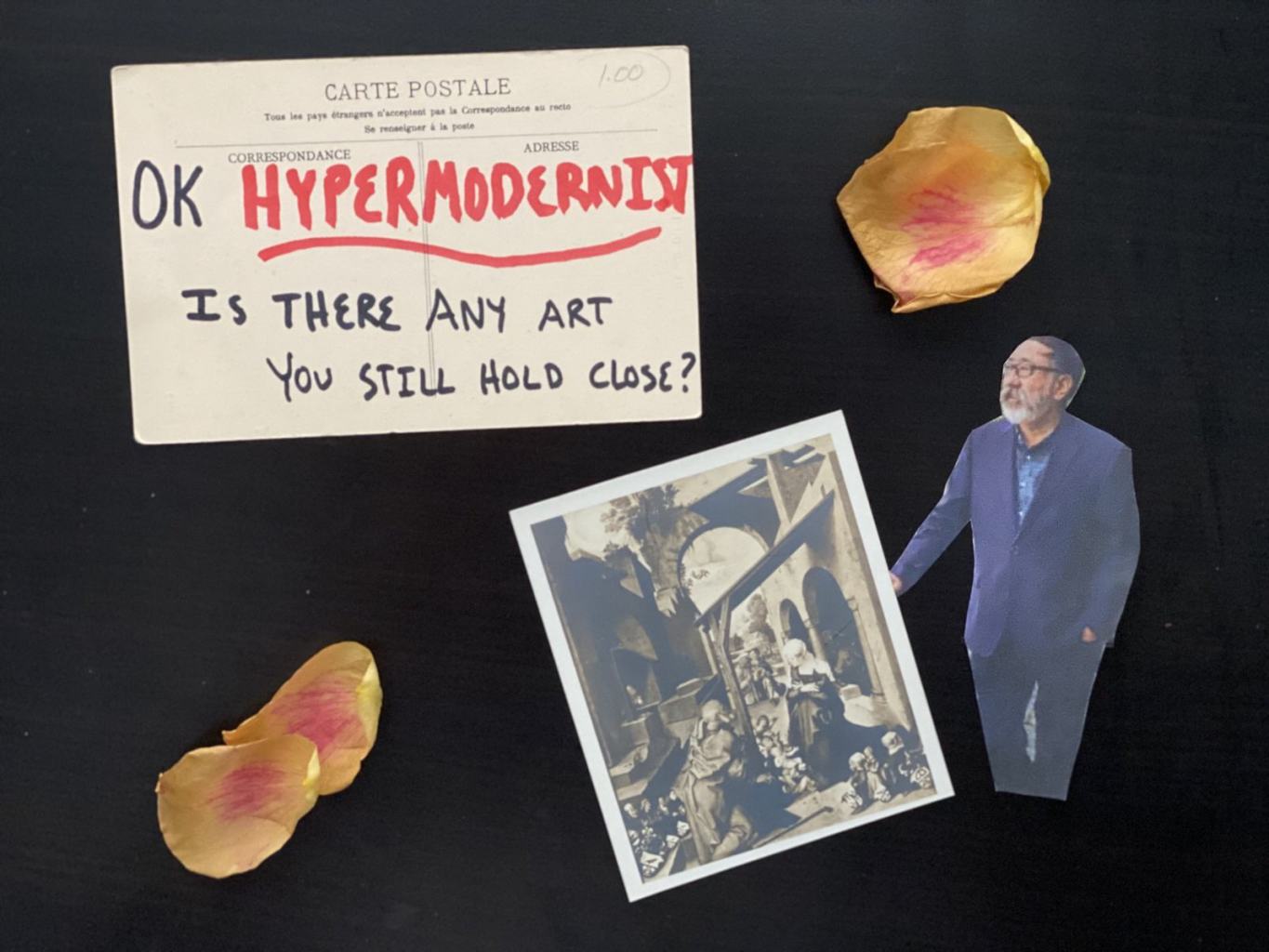

It’s embarrassing to say in this context, but actually I’m really happy to say this because I find that there are still so many composers—young and old—that don’t even realize how much of an influence their teachers have had on them. For me, I guess I’m kind of a hyper-modernist in that sense: I feel that this is not OK. GIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLE!!!

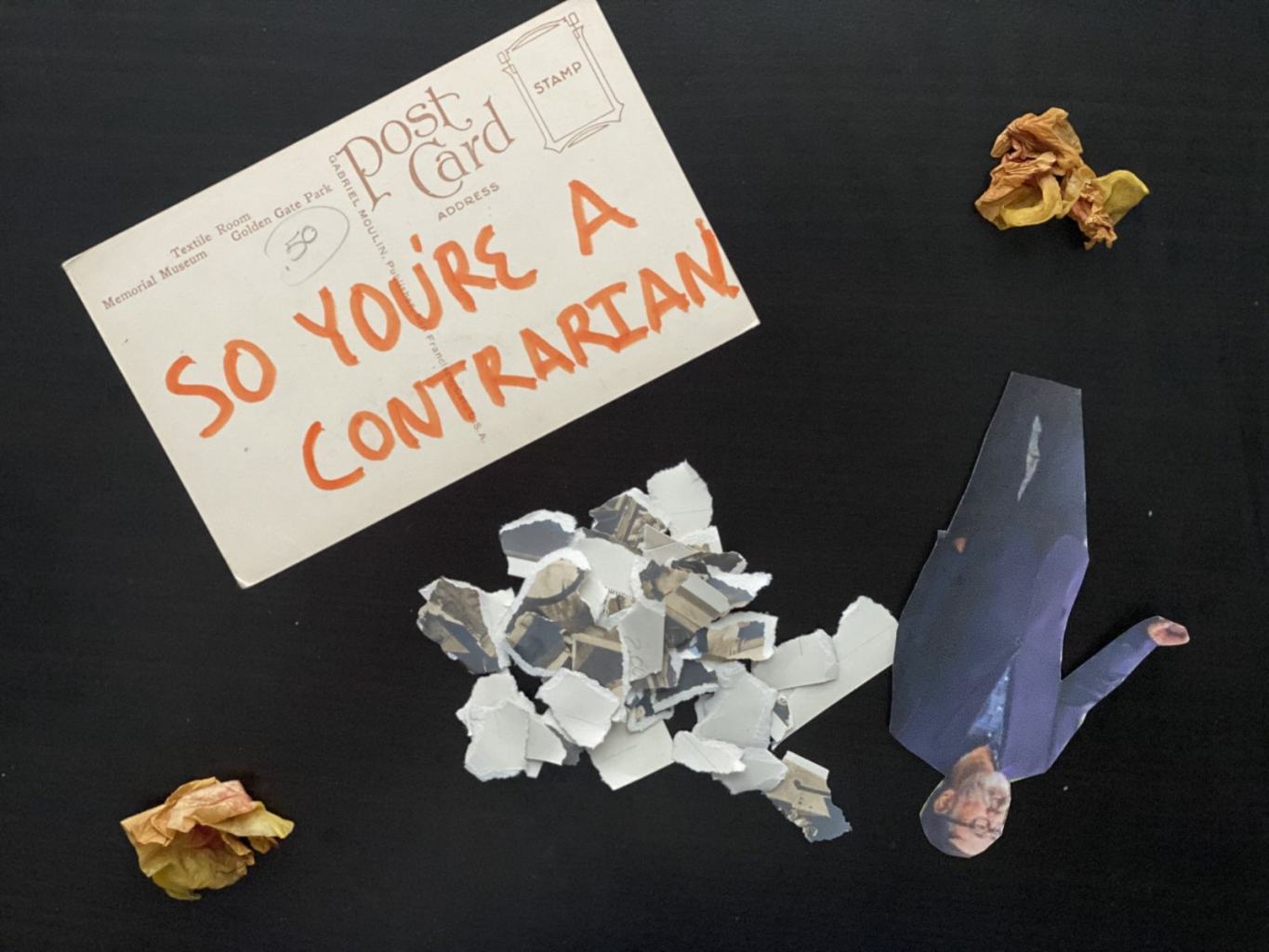

Rebellion is something I’m constantly going back to as fundamental to my thinking. One needs to rebel against these father figures! I rebelled against my father who was a scientist—so there you have the science vs. art rivalry. Then I went to Japan, and had to rebel against Japanese culture, because it’s the land of my ancestors and it’s so beautiful. But the ancient arts and cultures—which I’m still learning a lot about—are an authority that makes me a shadow figure. I had to look Japan—Tokyo—in the face directly and experience what it means to be living in a hyper-capitalist culture, rather than a medieval, distant, hierarchical—well it’s still hierarchical in the same way, but—hyper-classist culture. To be able to see it without the rose-colored glasses on.

For example: One day my koto teacher noticed that I was playing the traditional classical repertoire—from about the 1600s to the earlier 1900s—using vibrato. And he said: “No. We don’t use vibrato for the old repertoire.” Playing the koto, you have to press the strings to get the half-step, or even the whole step presses, which inflects the sound, but I realized much later that vibrato was my expressivity. He was saying: “We need to just leave the sound alone, because that’s nature speaking.” So I inevitably had to rebel against that very beautiful aesthetic of letting natural sound be, because it didn’t reflect this culture and society around me where at the same time business people, children were committing suicide…

Here’s a story about Feldman, and probably one of my best lessons with him. I was writing a piece, and it was very…. beautifully static, as one would do. But it accumulated in energy and suddenly there seemed to be a climax in the middle, and he was listening to this and he said:

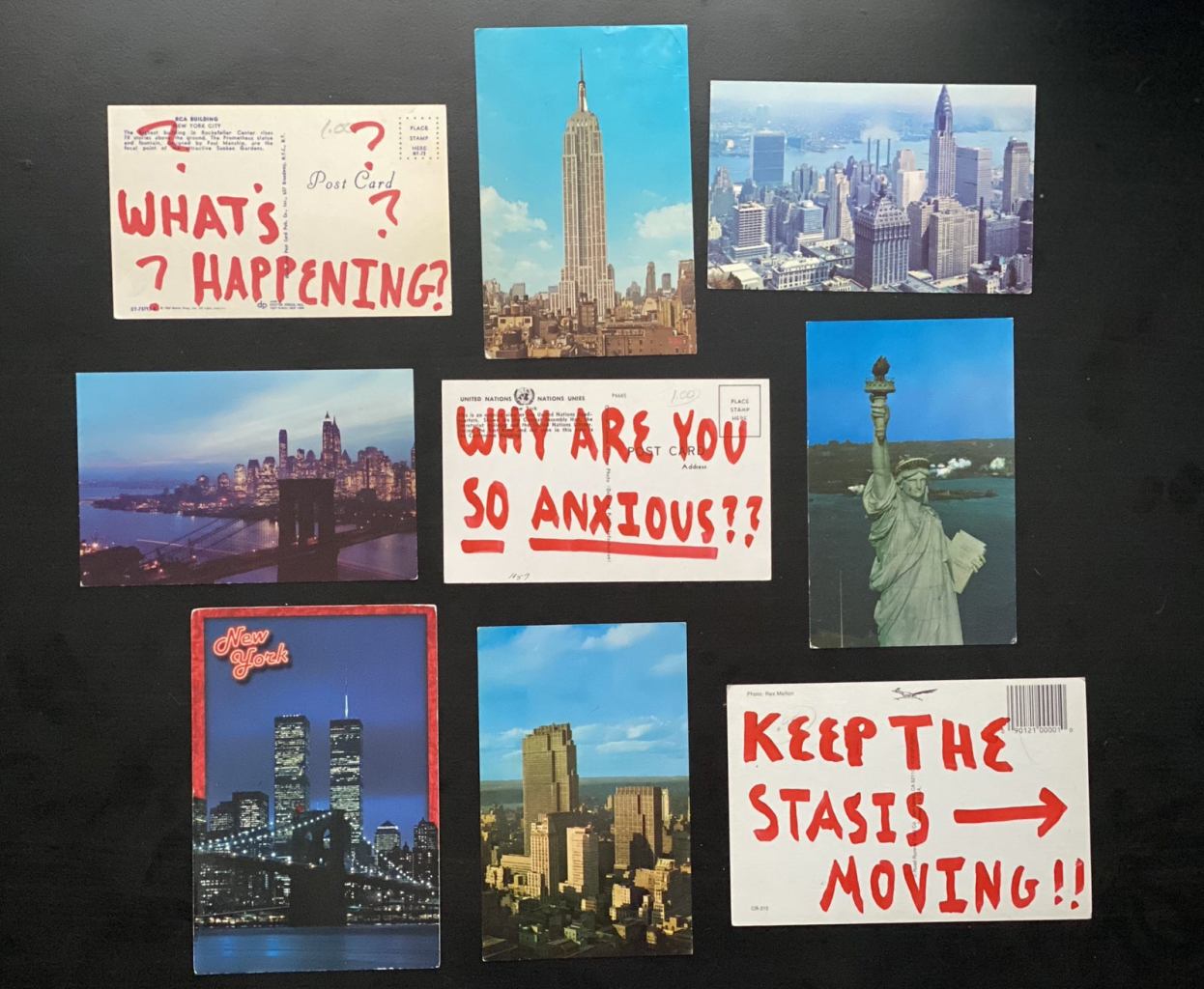

[Feldman asked] a really fantastic question. I always refer to it, not only in my thinking and work but also when I’m teaching. “Keep the stasis moving,” and “Why am I so anxious?” … Should I not be anxious? REBELLIOUSGIGGLE I had to ask myself, “Should we be anxious?” And I thought: Yes! GIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLE Yes, I think we should be anxious! This is a kind of argument. Do I think it’s very beautiful to keep the stasis and enter this extraordinary trance-like notion of what the mind does when one’s meditating? Yes. But this is also very familiar for me in Zen meditation, and of course I’m going to be rebelling against Zen. Not just because it’s religious—I’m an atheist, I should just say that, though that’s not because my father was an atheist…. NERVOUSGIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLE

Maybe there’s something there…

I’ll answer the question eventually.

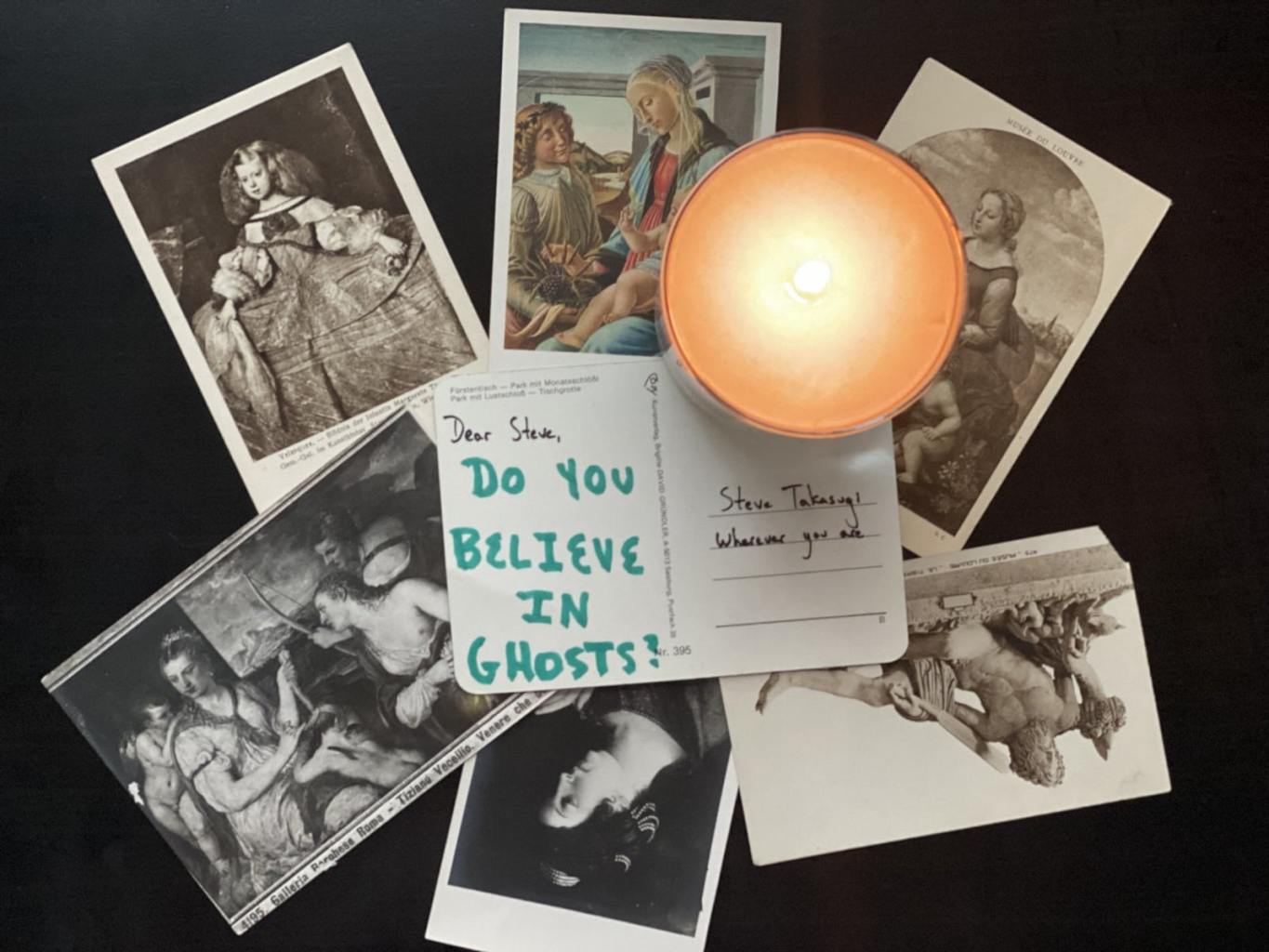

I was living in Japan, and the Japanese are big believers in ghosts, as you know from all their literature, their anime, their folk tales. And they don’t have feet, so that’s how you know who’s a ghost and who isn’t.

Anyway, I was teaching English at the time, and so I asked all my students: Do you believe in ghosts? And many of them said yes, that they’d seen them, etc. But I asked someone who worked in the ministry—I forget which ministry it was, but it was a bureaucratic ministry so obviously you had to be diplomatic—and when I asked him, he said the best answer I’ll ever get, and I wish I could give this answer too. He said, “Of course not, I don’t believe in ghosts. But I’ve seen one.” ASTONISHEDGIGGLEGIGGLEGIGGLE!!!!

You have to really analyze that. For us there’s a discrepancy, it doesn’t make sense: seeing is believing. But for the Japanese, there isn’t this dichotomous logic. It’s possible that you can see something but you don’t believe in it. It’s very strange, but it shows how different cultures can be with their logic. And that gave me pause; I thought about it for a long time. So: I don’t believe in ghosts. But when I go into the basement, I get scared that something is going to bug out! Why is that? If I don’t believe in ghosts, then my body is reacting to this bug-out spooky possibility. It’s like my brain thinks one way and my body reacts a different way. I can understand them, these dichotomies that don’t make sense.

Yes, the idea of ventriloquism is interesting to me for this double nature. In many ways I’m actually sandwiched between three cultures: Japanese or Asian culture, and American culture as distinct from European culture. In this sense, not just being Asian, but being a hybrid of cultures—being Japanese-American-European—and coming to these extraordinary artistic and spiritual notions like Zen with a European-American critical view: that’s the three-dimensionality that I’m looking for.

That’s why I say, “The best critique is self-critique.” Try to understand your own conservatism even when you think that you’re radical, because it’s lying some place. Looking at it turns it into a great source of creative energy and inspiration. It’s an opportunity. But it looks like a sleight of hand in some ways. Am I really being critical? Or is it some kind of hypocritical idea, self-mirrored play, the performance of criticism? Are you just going through the motions, are you just talking the talk?

I think a lot about Abstract Expressionism and Andy Warhol, and their relationship—and to some degree Philip Guston. All my friends hate Andy Warhol.

No, no! But don’t you need an Andy Warhol when you’re surrounded by Abstract Expressionism? PLEASEDGIGGLE I mean, I know that it’s obnoxious and that it’s complicit and all that but… I guess it’s maybe the religious component. Feldman talked about the “abstract experience.” His best friend Philip Guston was into that and then suddenly… Do you know the story about his cartoon paintings?

Morty and Guston were best buddies. But before Guston became an Abstract Expressionist, he was a muralist. Total representation! I don’t think all that abstract stuff was ever totally his nature. So when art started becoming representational again and his cartoon paintings emerged in the first showing, this was going to be problematic, because [to the Abstract Expressionists] what Guston was doing was kind of traitorous. In any case, Feldman came to the showing and Guston said: “So Morty, what do you think?” And there was this silence, he hesitated. And then Morty said: “Oh. They’re great.” And then they never talked to each other again.

I think about that a lot. Whose side am I on? Strangely, I’m on Guston’s side if I have to be honest. That critique of extraordinary beauty and extraordinary phenomenalism and that allegiance to nature. The critique that any type of depth—whether you’re talking about historical depth or emotional depth, whatever depth you’re talking about—is conservative. This is what I’ve been talking about this whole time: depth, beauty, they’re undoubtedly extremely powerful. When I see a Franz Kline painting, what else is there to do? It’s a feeling of the absolute. For me this is a religious experience. It isn’t so much a house of mirrors: it’s authoritative. But someone like Andy Warhol comes along and throws you a good curveball. He’s the beautiful thorn in the paw, or the sand in the oyster that makes the pearl, and you have to contend with that.

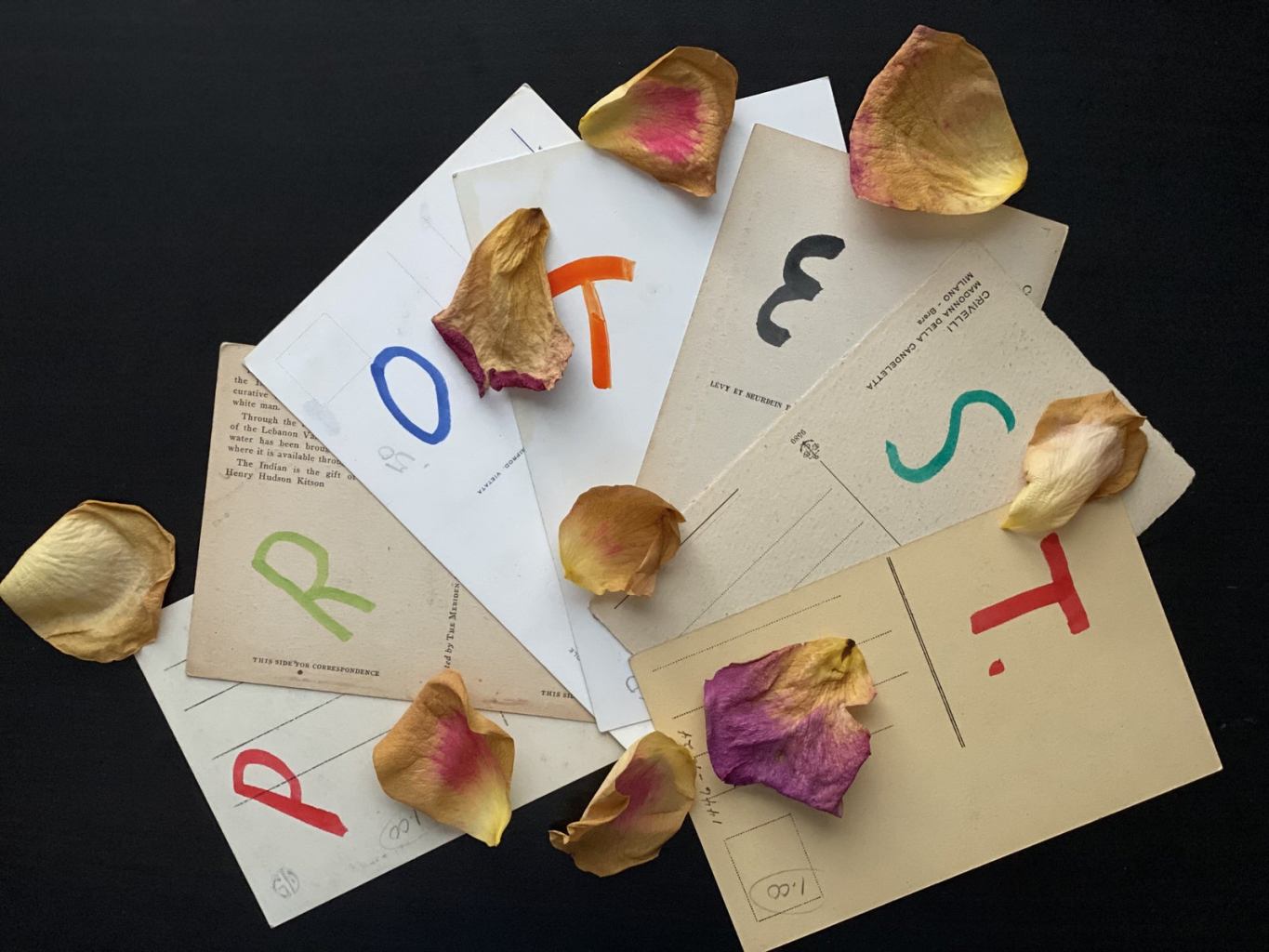

I actually think postcards are really interesting too. You only have this little square, so what are you going to say? You can’t really get into it; it’s an aphorism. But also, there’s no envelope. It’s naked! Which means that, if you write something intimate, you’re daring that someone else might intercept it. You’re taking a risk. There’s no clothes on it to hide it, just the content. I like that idea. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.