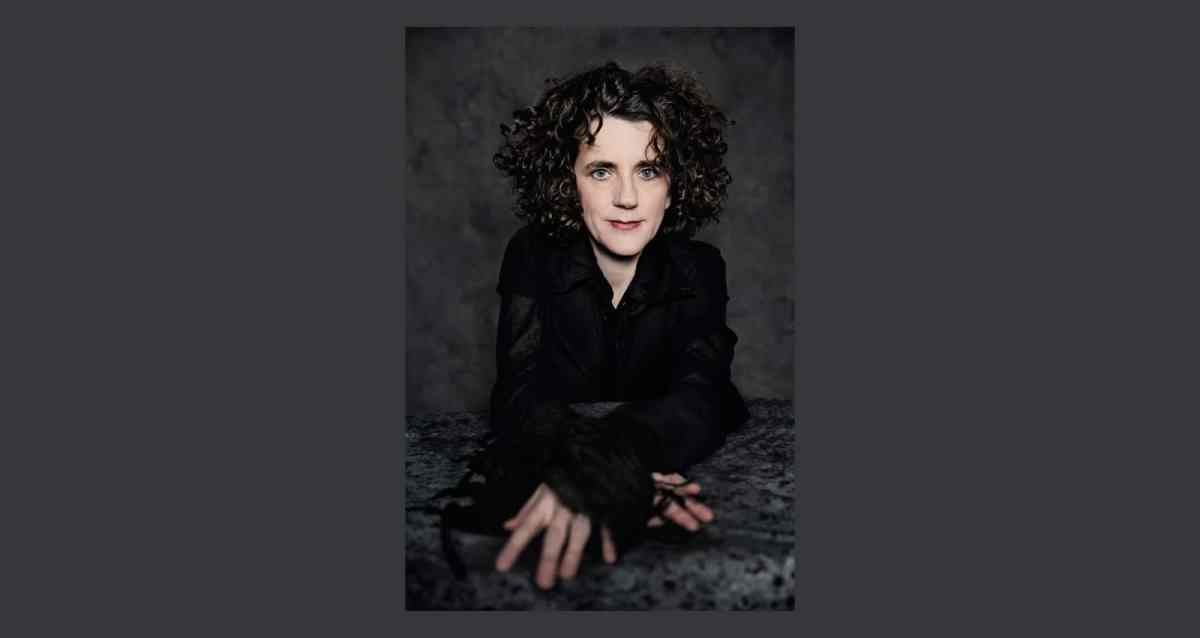

This interview took place in November 2015, and is reproduced here in an abridged version. We spoke with Neuwirth about the persistence of the patriarchy in classical music, the new generation of women composers, and her recent and older works.

VAN: I feel there’s an imbalance between the genders in our musical society. Are quotas and additional funding for female composers helping to improve the situation?

Pressured by unrealistic expectations it’s easier for many women today just to perpetuate the male system of meaning. Some women have, on the other hand, discovered that it’s time for them to focus on women’s issues. But where were these women—mostly of my generation—25 years ago, when I was already questioning how this hegemonic system of language and power operated in our field? In the 1980s and 1990s you could already read significant women theorists on the topic; I had been doing so since I was 15. To take Austria as an example: it was possible to engage with the work of Valie Export and Elfriede Jelinek or many other unflinchingly independent-minded, courageous women artists who were creating a diverse body of work. It was all there. Why didn’t the women who are interested in gender issues today speak out then? Are they doing so now only because meanwhile it has become socially acceptable in our part of the world, and moreover because the topic has finally made its way to our conservative field of art? Or maybe because they think an involvement in women’s issues gives them personal gratification and power? The crucial question is, when do you raise a critical voice? When do you first identify the problem? You don’t just wait until everyone is already shouting it from the rooftops and you can no longer be attacked for speaking out.

I addressed the problem of equality over 25 years ago, when nobody else in the stuffy Austrian music world was doing so. In the late 1980s, when I arrived as a female composer on this (male) scene, I was a lone voice in the wilderness. With my statements I stuck out my neck for many women, especially women composers.

As I said, we are in the world of classical music, which is still white, male, and patriarchal—in other words, still rooted in a hegemonic system. And generally speaking all linguistic systems are still male, because an alternative female language hasn’t been found yet. That is not to say that at times women are not allowed to initiate things. But for the most part, a confrontational woman who consistently rejects false images and embellished tales of life and art is not taken seriously, but treated with contempt. In any case, the history of my life as a composer is also the story of the constant questioning of a woman’s ability to compose. And that’s demoralizing.

From your perspective, how has the discrepancy in the treatment of men and women changed in the contemporary music world since the early 1990s?

I think it has become nastier. A more “elegant” chauvinism prevails. You can’t refer to problems directly, or be as obvious as you could be during the “leaden time” of the late 1980s. When a woman calls attention to injustices today, often the following happens: her objections are dismissed as hysteria and then “the empire strikes back.” She is kicked out and declared an adversary without further explanation or discussion.

Although I’ve often been robbed of my self-esteem and the belief in my ability, I’m continually required as a freelance composer to motivate myself. Furthermore, as a freelance, peripatetic composer, I’m completely dependent on the good will of decision-makers. And I’ve often been referred to as “That impudent brat!” You’re impudent when you’ve no claim to power. But does anyone call a (young) man “impudent”? Instead he’s “That gutsy fellow” and “gutsy” in this context means he commands respect and attention. From a hierarchical point of view, a person is considered “impudent” only from the bottom up. And so if someone wants to get rid of an “impudent” woman, it’s best if she is rudely disposed of by the “gutsy fellows.”

After 13 years it’s still unbelievable to me that my commission for an opera with a wonderful libretto by Jelinek was canceled. This was not a commission that we begged for; it commission was given freely. Although it had been publicly announced several times, nobody in the music industry took our side when the commission was withdrawn for no good reason. This incident was swept under the rug as if it had never happened. And with regard to my opera “Lost Highway,” with Export as stage designer, and Jelinek as librettist, the dramaturge sent me an e-mail, which I have kept: “Three women are just too many.”

Do you think the male-dominated system reacts this way because it feels threatened?

Yes, exactly. No matter what, power feels threatened by art, and apparently especially threatened by a little woman in a male domain. 25 years ago, discrimination against women composers was even more prevalent. For example, it sometimes came from the wives of fellow composers, who would say to my face, from woman to woman, so to speak, Your works are only being played because you’re a woman. All the things I’ve had to listen to over the past three decades! And from all possible sides! It’s really incredible and depressing. The gentlemen in this field were evidently shocked that a young “impudent brat” would dare whittle away at their privileges, not to mention think for herself, have ideas of her own, and gain recognition. All this was regarded as a transgression, as presumptuous.

There were at least some forums for woman composers in the 1990s, such as the series “Komponistinnen und ihr Werk,” which took place in Kassel, Germany.

I was in Kassel once, when I was about 20 and in search of role models. But it is disillusioning if over so many years neither the structures, nor the mechanisms of how decisions are made have changed. For example some proudly broadcast: “Now we’re presenting an all-women festival,” or “Now we’re focusing exclusively on women conductors,” and yet if their inner attitude is, “Now we’ve done our part and may continue on as before,” nothing changes. Ultimately, what this means is—and this applies to all minorities who have ever stood up for their rights—that different people should come together with more openness, understanding, and kindness, and not with arrogance. Opposites and different ways of living and expressing must be able to interact without anyone constantly having to point this out. Nothing has changed when it comes to the supremacy or dominance of institutions or power. But I would rather like to experience something new, something that triggers new emotions and thoughts in me.

Then again, to a certain extent, there are consolations, for instance, grants and composition awards specially conceived for women composers…

Which is necessary. At the beginning of a composer’s development grants are important. But something must change structurally – and I hope one day this will actually happen – because if it doesn’t then all these years I’ve just been talking until I’m blue in the face to no effect. It will have all been for naught if the other side isn’t willing to react in any way, as then such grants and awards are only token gestures. I don’t think they change the system. The important thing would be to create an awareness of the fact that things actually need to change. I mean, where in the world are all the women composers who are being performed internationally on a large scale?

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

I get the impression that in the generation after yours, a higher proportion of women composers is active and known to the public.

Yes, and that’s a good thing. But you shouldn’t forget that we were pioneers in all sorts of ways. Women of my generation had to break through substantial gender barriers, and so there’s one thing that makes me sad: I yelled out “into the dark forest,” also with regard to the need for an acceptance of contemporary composing per se, and tried to raise awareness in society for the conditions of so-called “contemporary composers” and to give them a voice. But to speak out politically as a female composer in the early 1990s was strongly disapproved of. This was dismissed by my male colleagues as a distraction from the “real” concerns of composing. They were, and many still are, aloof, condescending, and distrustful. Apparently, back then my topics and music were too “popular” and as a person I was too unconventional to be taken seriously.

Many younger composers express political views, but don’t necessarily understand the history behind them. Are their views more superficial?

I can see this as a counter reaction, but I believe that we should be aware of the fact that there is something at our disposal which has already been established. This is something that can also be traced back to a sociopolitical context. It wasn’t until the 1970s that a number of laws were changed, because until then, at least in Austria, the law had stated, among other things: “It is the wife’s duty to obey her husband.” Under Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, the first Minister for Women’s Affairs, Johanna Dohnal, worked towards changing this and many other laws for the benefit of later generations. That is to say, there were people who had made it possible for us women to deal more freely with our lives and work. If someone was blessed with the good fortune of being born later, when suddenly more was possible—that’s great for them! But I feel like it’s cynical to want to blank out those who fought for these things in the first place.

But to get back to music: as a woman composer, you’re still discriminated against, though it’s true, now it’s done more cunningly. You can get a bad reputation really quickly, that is, if you don’t do as demanded by the different parties and behave as expected. But who wants to live with a bad reputation? It’s no fun. There are consequences, as I’ve experienced several times. I believe many people just aren’t willing to go through this. That is, unless “being critical” becomes “in”—then people are pleased to have such a label attached to them.

People tend to cultivate a “bad boy” image only if it doesn’t actually harm them, which brings us back to language: the term refers to someone who is “gutsy,” as you put it, who commands respect. But is there such a thing as a “bad girl” image?

If it ever existed then it was in the punk scene. And that’s where I come from. When I was 15 it was what interested and influenced me. But such an image was permitted only on the fringes, as a subculture, so to speak. The higher you get in so-called elite and exclusive circles, the more patriarchal and segregative the structures become.

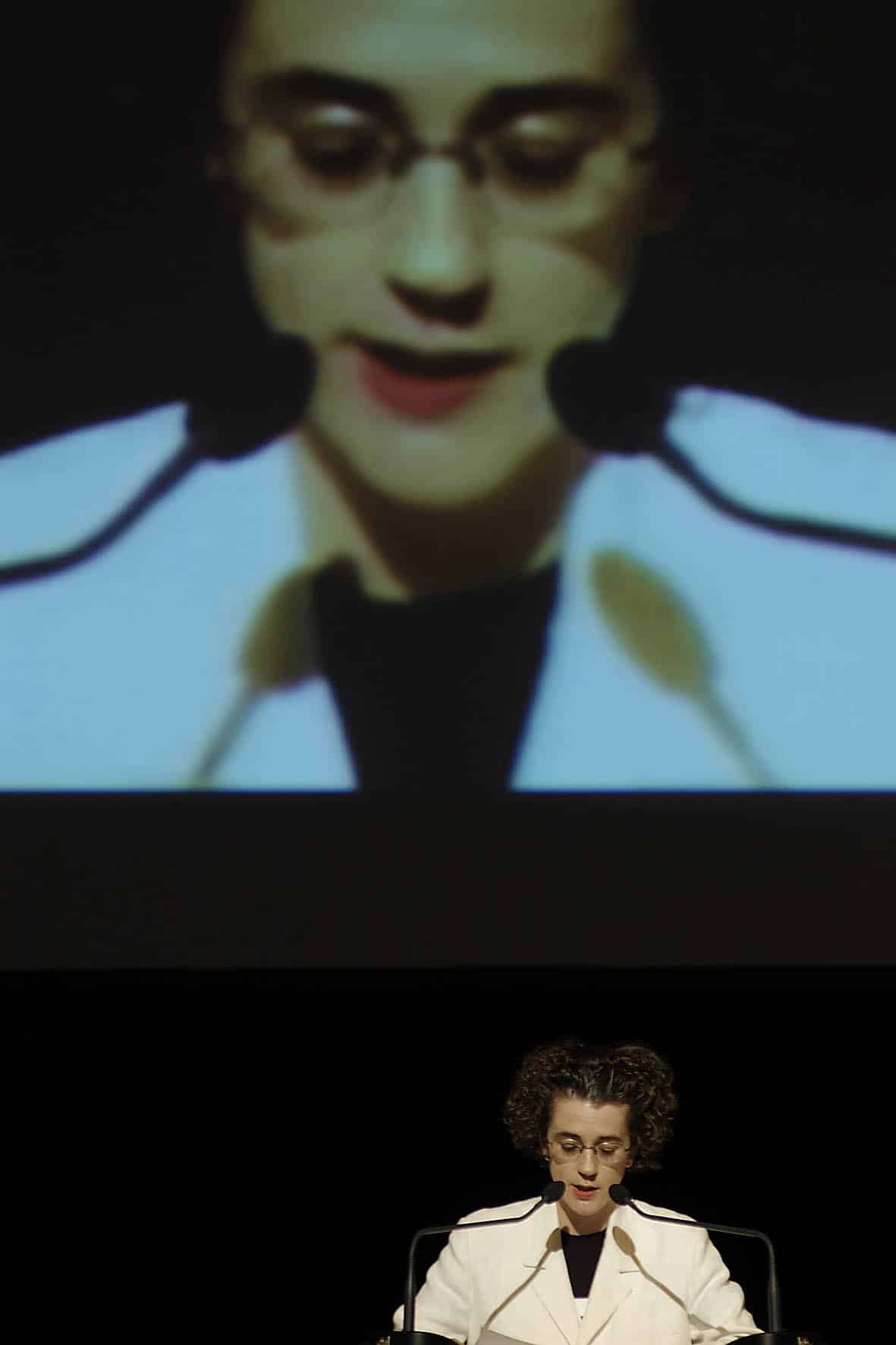

Because I wanted as a composer to make a statement about the present, I collaborated for a great many years with Elfriede Jelinek, that superb, headstrong writer. For me the way some opera-house directors have behaved is an absolute sign of how a standardized male system prevails in my field. Especially in our case, when as two women (I mean, how many collaborations were there in the 1990s between a woman composer and a woman writer?)—one of whom was quite well known and the other very famous–we were summoned and patronizingly told: “You may now create an opera together.” So the writer, in her enthusiasm, writes an amazing, biting text. But then with the arrogance of the music industry, and here’s where their presumptuousness comes in, they state: “She’s not capable of writing a text.” I have this in writing! And three months later, this very same writer is awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature!

In contrast, who would have disinvited an already invited male composer and male Nobel Prize laureate? Instead, when it comes to one of my male colleagues, to make the work even more important people are continually stressing that his male librettist is a Nobel Prize contender. But I collaborated with a real Nobel Prize laureate and we were axed. This says it all, there’s no need to add anything more about how women are treated in the classical music world. And this story didn’t happen 25 years ago, but began in 2001 and ended in 2005.

Does outward appearance or the enactment of femininity also play a certain role in the acceptance of women?

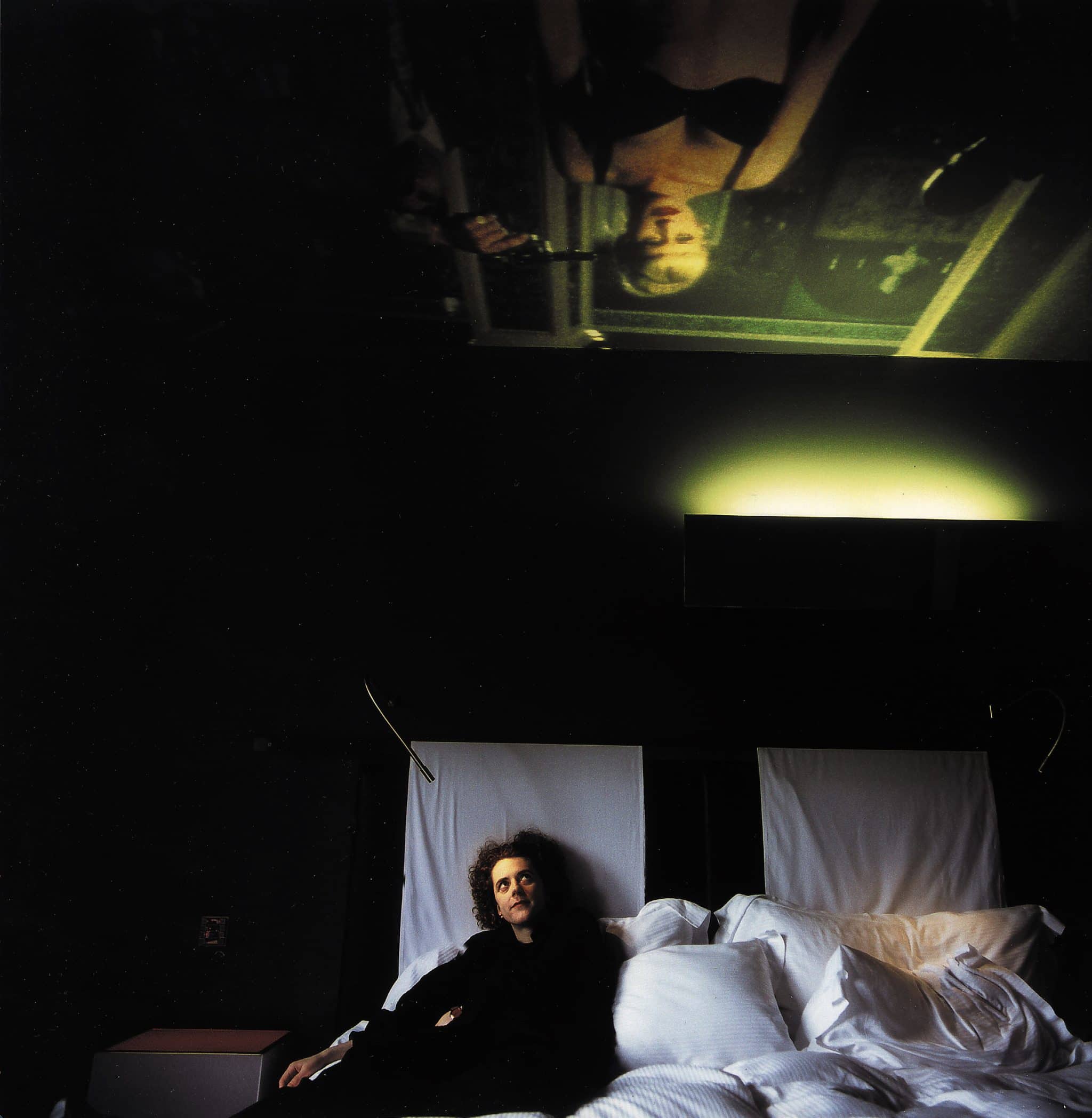

Recently, when people saw the cover of the program brochure for the performance of my work “Le Encantadas” in Paris, many of them said to me: “Oh, you’re pretty, too!” Of course, why not? I can be pretty too. But do I constantly have to be “identical with myself?” I find this absurd, and it has never been something I’ve wanted–that as a woman you should achieve your goal or success by making “detours” with sex or being cute. Why not just focus on the work? Of course, as I realize, this was and still is naïve of me. I could have always made it easier for myself.

I have the feeling that this topic has also played a role in your work. For instance, the short film “Die Schöpfung” (“The Creation”), which you created together with Jelinek in 2010, would probably not have been made if you hadn’t had all these negative experiences.

Yes, but that’s a different topic. For me it has always also been about an ironic refraction, as in Thomas Bernhard’s statement about Zwangswitze (“forced jokes”), which you need in order to cope with a hopeless situation. A paradox full of absurdity and melancholy, despair and defiance. In effect what I’ve always tried to do in my pieces is to elude categorization, because I don’t want to be pigeonholed. Which in turn has, for me at least, meant that I could not in fact be categorized, and so now people say: “With her you never know what you’re going to get.” As if multifacetedness lacked quality. However, with my male colleagues it’s exactly this that gets hyped as great and masterful.

In fact, there’s no fixed concept of gender, rather you can always transform yourself performatively, and this has for me had an impact on the very language of my music – it’s what I play with, I’m always playing with different facets of this.

Of course, this differentiation has also affected your male characters, for example Jeremy in “Bählamms Fest.” It’s also apparent in your explorations of Klaus Nomi, who personifies the idea of gender as performance. It also protects works from being interpreted exclusively from a feminist perspective, since the main characters—both of whom are outsiders in society—are too complex and contradictory.

That’s true, it just wouldn’t work and would be too one-dimensional. You have to—and here’s where it all starts—grant the other side the same right of existence as your own side. If I demand something, then there has to be the possibility for the other side to demand something too. Thus complex issues have to be made recognizable and understandable for many observers, that’s really important. But then I need, at least in a music theater work, to let things collide like in a lab experiment. Like with David Lynch: “the stage as catastrophe.” But from the critics there has never been an attempt to examine this aspect of my work in any depth. And so the female composer disappears behind her male colleagues in terms of how her works are received, especially her big works.

Perhaps something positive in conclusion?

It’s important that things become fairer for males and females and all others. I’m really interested in other people, which means that for me every situation that I observe, learn, and deal with contributes to the adventure of composing.

Since our interview, Georg Friedrich Haas gave an interview in VAN, and I wanted to ask you what you thought of it. For me, it raises some very problematic issues. He says that, following a discussion of a lecture at Darmstadt, that “we agreed that the most feminine music we heard [there] was by Morton Feldman, and the most masculine was by Olga Neuwirth.” What is your opinion of your colleague’s remarks?

Actually I would prefer to say nothing about this discriminatory interview. Not that there wouldn’t be plenty to say, as much of it is outrageous. But since this “very successful” colleague—as he refers to himself in The New York Times—uses my name to make an extremely stereotypical categorization, I feel I must react.

The sexuality or sexual preference of a person is totally unimportant to me. He should be happy to have finally found himself. But to publicly boast about it and then use living and dead colleagues for his own agenda and thereby discredit them is disgusting. He prides himself on being so political, but he speaks as if he he’s never heard that there are many different kinds of sexuality and ways of living one’s life? It is precisely one of the New York values, as people say in the city, to be tolerant toward others, and accept a wide variety of lifestyles. What’s more, his remarks reinforce age-old male fantasies that in our classical music business are allowed to remain uncontested, and therefore become publicly accepted.

Apparently there is a need to preserve misogynist clichés, as was also evident in the omission of positive adjectives in the critics’ reviews of my recent concert with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in New York. For decades the orchestra was rightly criticized for having almost no women in its ranks. And now for the first time in New York this orchestra performs a work by a female composer, excellently, and instead of acknowledging this as a step in the right direction, it is ignored in order to maintain the negative cliché. Apparently the fact that the number of women in the business is increasing and that they are being offered similar opportunities is threatening and disturbing for the social order of our classical music world. What for me is truly disappointing, and this is something I have been aware of for years now, is the fact that, unlike in other fields of art, in our field nobody protests when an artist expresses such discriminatory views. ¶

Updated 4/4/2016.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.