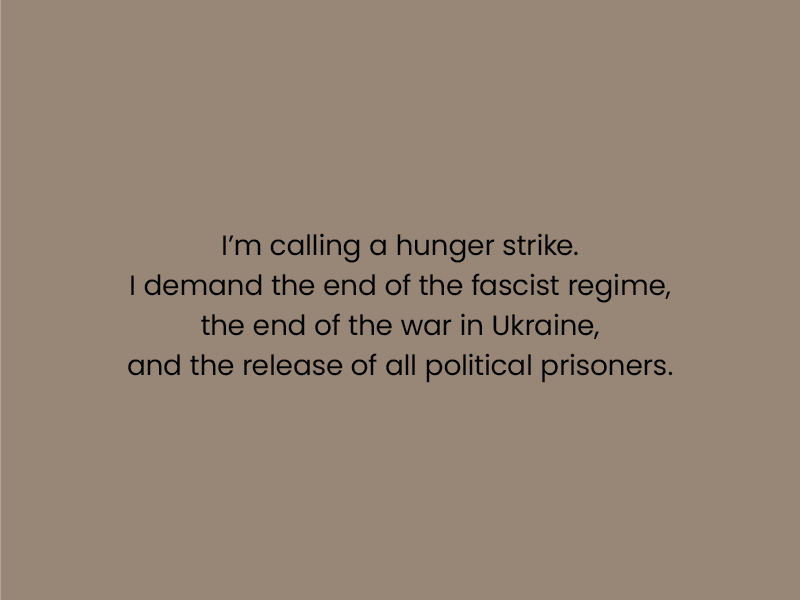

The pianist Pavel Kushnir died on July 27 at the age of 39 in a prison in Birobidzhan, Russian Federation, apparently of complications from a days-long dry hunger strike. In late May, Kushnir was arrested by FSB officers on charges of incitement to terrorism. On his YouTube channel, Kushnir, under the username Inoagent Mulder—he was a fan of “The X Files”—had posted four poetic monologues that included criticism of the Russian government and the war in Ukraine. In the final video he described the Bucha massacre as “the disgrace of our motherland,” called for resistance to the regime and the war, and demanded the release of all political prisoners. According to friends, this channel had five followers at the time of his arrest. Some of those close to Kushnir only learned of his detention and the subsequent hunger strike after his death.

After studies in Moscow and Yekaterinburg, Kushnir worked as pianist for 12 years in various provincial Russian cities. During his lifetime, his artistic activities never reached a wider audience. He remained largely unknown inside and outside Russia. Now, people are searching for the traces this idiosyncratic artist left behind.

A dazzling musical and literary oeuvre has begun to emerge. In 2014, the publisher Zaza Verlag in Dusseldorf brought out his anti-war novel Russian Cut; it was not reviewed at the time. In the summer of 2022, Kushnir finished another novel, Noel. He was apparently convinced that the book would never be published, and the manuscript is unaccounted for as yet. In an interview with local radio in Birobidzhan, he described working on the novel for eight years, creating a structure analogous to the one theorized by the astronomer Johannes Kepler in his Harmony of the World. Since his death, interviews with and readings by Kushnir have circulated on social media: an essay on the German painter Uwe Lausen and recordings from the 51-part radio series “Mazurka Wednesdays,” in which Kushnir analyzed all of Chopin’s pieces in that genre from January 2023 to the end of March 2024.

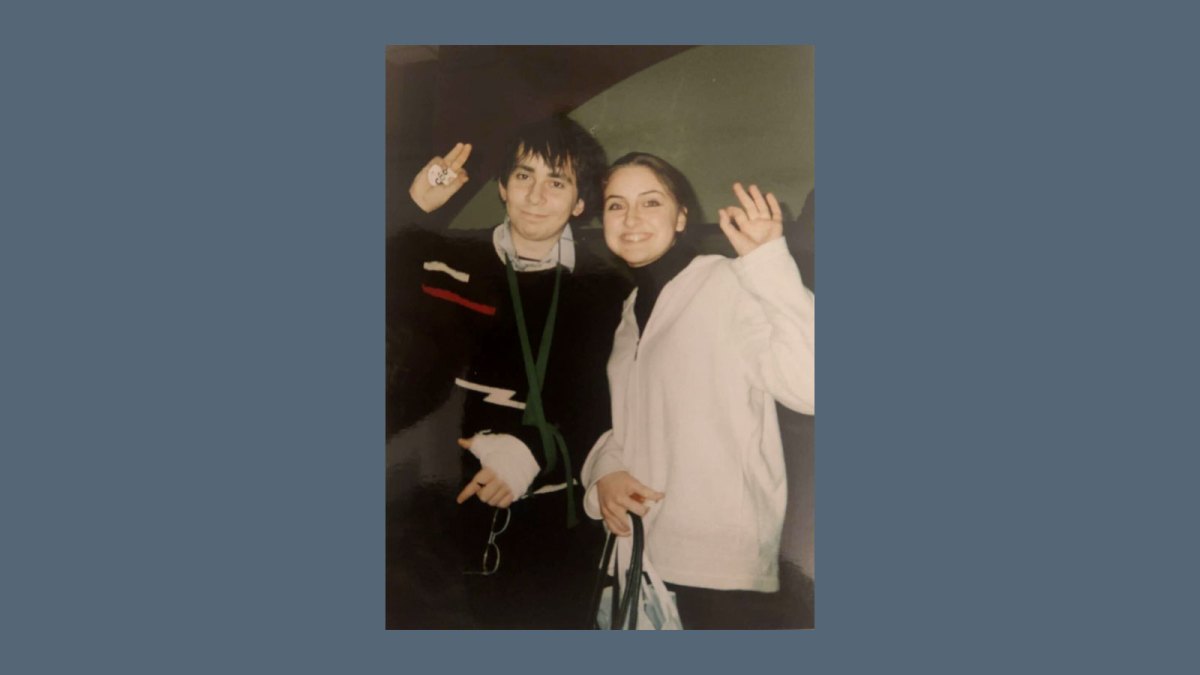

Who was Pavel Kushnir? “I grew up with him,” the pianist Olga Shkrygunova tells me. “I took his extraordinary qualities for granted.” She and Kushnir had been close friends since childhood. He continued sending her manuscripts and texts as they both grew up. Shkrygunova moved to Germany in 2012 and finished her master’s degree at the Rostock University of Music and Drama in 2014. The same year, she joined the chamber music ensemble Salut Salon, where she remained until the end of 2023. I reached Shkrygunova on a Monday morning through video call at her Berlin apartment. “The first days were filled with the organization of Pavel’s cremation,” she tells me. “Yesterday was the first day I was completely alone. The worst part is about to start.”

VAN: How did you first meet Pavel Kushnir?

Olga Shkrygunova: We’re both from Tambov. We went to music school together, starting from when we were six years old. His mother was my teacher. She was also my mom’s teacher, and I met his dad and grandfather. He was a really close friend, almost a relative: A person who was with me and my husband our whole lives. I looked in the dictionary and I think “playmate” is a good translation, though a somewhat old-fashioned one. After the invasion we were in closer touch again. We had very similar views against Putin and the war.

What memories do you have of your time in music school together?

We played the same concerts and competitions, and he was always better. He always got first place and I always got second place. That stayed true until I was 18: I’m close, but not quite as good as him. I remember those moments well, thinking, “Argh, he played better again.” Even as a child people gossiped about his talent: how quickly he learned things by heart, how early he began composing. I took it for granted. Everything Pasha did was extraordinary, he stood apart from normal life. Many people, including famous musicians, are asking me now: “He’s so good, so unusual, why didn’t no one know him? Why was he living in this little provincial town, why didn’t he have a career?” I used to post his recordings and about his book on the Russian social media site VKontakte. There were never any responses. That’s really, really sad for me, of course.

After his concert exam in Yekaterinburg, Kushnir spent seven years as a pianist with the Kursk Regional State Philharmonic Society, then three years with the orchestra in Kurgan. In 2023, he became the pianist with the Birobidzhan Regional Philharmonic. How would you answer the question of why Kushnir remained in the provinces?

A “normal” life, a bourgeois life, was impossible for him. And he was really, really out of place marketing himself. He wasn’t against it, he just wasn’t good at it. For example, I told him about Salut Salon, which was in a sense the exact opposite of what he was doing, but he thought it was great. He was completely open to the idea that there are different paths in this life, but it really was impossible for him.

He and I took the entrance examination for the Moscow Conservatory in the same year. I got in, he didn’t. Do you know why? Because I’m nice, and blond. He wanted to play Schumann’s Fantasy in C Major. The jury told him to play just one movement, to which he answered, “I can’t do that. Schumann conceived the piece as a whole. If I just play one movement, I’ll ruin my concept.” In the academic world, and especially in Moscow, you need the right connections. If you don’t have the contacts, and if you’re not “nice,” it’s really tough.

How aware were you of his political views?

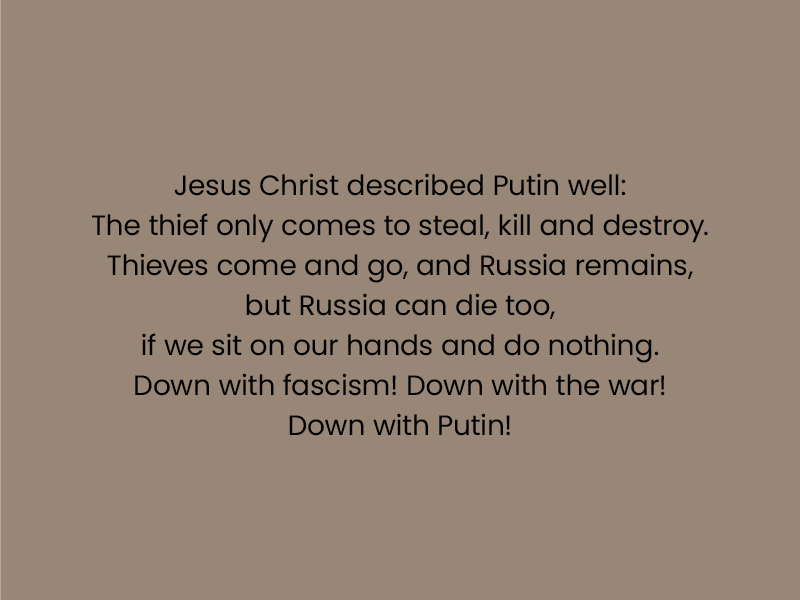

He had thought that Russia was becoming increasingly fascist for a long time. In 2012, he visited us in Moscow to take part in the Bolotnaya Square protests. He went with a sign and had a brief confrontation with the police. He was already radically opposed to Putin and put great hopes in the demonstrations. His first book, Russian Cut, includes many reflections against fascism in Russia, and many anti-war statements. But it shouldn’t be reduced to its political stances. I’m convinced that it has real value in the history of modern Russian literature. After the start of the war in Ukraine, he gave out flyers in public spaces around Birobidzhan. At night he hung up posters against Putin and fascism: “Please, people, open your eyes.”

He was arrested for the political messages he posted on his YouTube channel.

He was an artist first and foremost. Everything he did was poetic. He had just a handful of followers on his YouTube channel, which makes his arrest even more absurd and tragic. On February 24, he sent me the diary he had been keeping since September 2022. I didn’t have the strength to read it, but I started yesterday. I believe it’s an important historical document, by a person who understood what was happening. He was so far ahead, always ready with a quote, a wide reader who found a lot of connections to music. In a letter, he gave me permission to publish his diary. I’m talking to publishers about it now.

Do you think he sent you the diary because he knew he was going to be arrested?

Yes, 100 percent. Every once in a while he’d email, “I’m drinking tea in my kitchen, but I don’t know for how long.”

What did you learn about his time in prison?

Nothing at all. I talked to him on the phone in March. I was a little worried because of his long hunger strike, but he wasn’t in jail yet. Probably I should have paid more attention to him. But he’s an adult, and I have a family. I couldn’t google his name every day.

He went on hunger strike before he was imprisoned?

Yes, twice. The first was 20 days in May 2023, the second around 100 days until March 2024. But he was drinking liquids. The next time I heard about him, it was already too late. His mother knew he was under arrest, but she didn’t tell anyone. You know, when the draft started, he was almost ready to come to us [in Germany]. But then he wrote to me, “What a pity, my passport is expired. It’s too late.” A normal person would think, I’ll go to the passport office, get a new passport and try to get an EU visa. I said I’d send him an invitation and all the necessary documents. But for him the expired passport was a sign. He wrote, “Someone has to stay here and open their mouth, to show that someone has the courage.”

Did he feel an unusual sense of responsibility?

Yes, of course. In a letter from September 23, 2022, he wrote, “I think it’s still possible to resist fascism in Russia. I even believe it’s our historic mission to beat fascism, and that we can only achieve that by overcoming ourselves. Fascism can’t be tamed or diverted. I believe it must be destroyed.”

What were your first thoughts when you heard of his death?

I was not surprised, but that it happened so early and so fast did shock me. He was such a strong-willed person. Still, I couldn’t imagine that he would die during a hunger strike. And that no one helped him. It was a feeling of: “Oh no, shit, it really happened.” When I got the news I was on vacation. My husband and my daughter were asleep. The air smelled like the sea, everything was so nice, so comfy. And then I thought, “I’m not going to tell my husband, because this is our personal catastrophe.”

Was there a cremation in Birobidzhan?

Yes. We had to get a notarized document from his mother allowing the funeral home to burn Pavel’s body. There was a brief ceremony on August 8. Five people came. There was a lot of attention to the case in Russia, but Birobidzhan is far away and fear is omnipresent. The urn is now being brought to his hometown, Tambov. The real funeral will happen there.

What do you know about the conditions of his detention?

Now all those questions are being raised: Was he abused? I can’t imagine. I don’t want to imagine. Despite everything, we’re all human. He had a very soft voice, he was never aggressive. That’s why he chose this form of protest.

You can request an inquiry into his detention conditions online, but I think we all know that the agencies can write whatever they want. The friends who organized the funeral in Birobidzhan were worried that the prison wouldn’t give them his body if an autopsy was requested.

Considering the personal suffering and tragedy of Kushnir’s death, this may seem like an abstract question. But do you think he would have hoped for his death to send a message?

That people like him are still out there. That there are Russians like him who are still out there who are unbowed, who are fighting the system. But these messages only reach the people who already get it. They are closed circles, and we’re not getting outside them.

What is a memory of him that will stay with you?

Mostly his sense of humor. I can’t translate it, because it was so precise, so strong and so dark. When I think of his jokes, I’ll always be laughing. ¶