We do not speak of horror.

(Well, not in public, anyway.)

It has been the tacit agreement of two generations of new music that cinematic horror is the forbidden aesthetic referent: a real and prevalent influence but one whose admittance is generally deemed more detrimental to the cause than worth its expository fruit. In private conversation, horror and its various arenas—the visceral, the abject, the cruel, the abstract, the formal, uncanny, or monstrous—crop up as active touchstones for a vast array of compositional paradigms. Rare is the composer without a charged relationship to filmic violence; some go so far as to make it literal (Olga Neuwirth adapted David Lynch to opera in 2003; Missy Mazzoli did the same with Lars von Trier in 2016). But in the uphill battle to secure credit for new music’s anti-comfort aesthetics in mainstream classical sectors, such brazen citation of horror as a serious interlocutor is widely considered too risky to be worth it. The composer who announces “my music is horror-influenced” offers dangerously potent cannon-fire for suspicious lay attendees all too eager to reduce noise music to a kind of torture. At even the mention of the word, that Latin affect of horrēre, of hairs-standing-on-necks, overtakes more serious (and worthy) considerations of form and aesthetics. The invocation of horror leaves open the door for coarse reductions like “contemporary music reminds me of a slasher soundtrack,” a dreaded comment which arrives, intentionally or otherwise, as a calculated delegitimization of acoustic autonomy whereby sound is stripped of force in its equation to some imagined but more palatable image. The embedded assumption—“You’re only writing this to scare me”—evacuates new music of any serious aesthetic weight. Better to keep that door shut.

Composers have thus taken considerable pains to avoid associations with horror—although that rule is decidedly one-sided. Film has found contemporary music endlessly useful for exactly that frustrating simplification. Kubrick’s deployment of Ligeti in “2001: A Space Odyssey” is the classic example; Feldman, Paik, and Adams all saw Hollywood roll-outs in 2010’s “Shutter Island”; and as recently as 2017, Yorgos Lanthimos’s “The Killing of a Sacred Deer” drew heavily on the Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina to soundtrack its tersest moments. In a more diluted but pervasive iteration of the phenomenon, a slew of Hans Zimmer acolytes pump out ambient soundscapes for Netflix suspense ventures, leaning heavily on sounds all pioneered by mid-century new music: snarling brass tags, looming percussion, electro-acoustic distortion, eerie treble chorus, and beating string drones can be heard in everything from “Squid Game” to “Dahmer.” The path of least resistance to affects of fear seems to now be through a host of new music clichés, all forcibly detached from the formal contexts that lent them significance in the first place, then lowered solely into the service of feeling.

And so when Kelley Sheehan points to “Hereditary”—Ari Aster’s breakout 2018 film about a family’s slow unraveling after the death of their secretive matriarch—as the strongest among her extramusical influences, that Hollywood-trained instinct to assume affective intent looms deadly close. The Chicago-born composer, one of the second wave to emerge from Chaya Czernowin’s Harvard tenure, has built a runaway career (sketches for commissions from MusikFabrik and Klangforum Wien are on her desk when I arrive) on a diet of heavy distortion, harsh noise, feedback loops, and a music as shatteringly visceral as it is technologically augmented. Her soundworld—gritty and breathless, a peristaltic ratcheting of force that tangles bodies up with an array of lo-fi machines—seems to invite comparison to techno-dystopias and structures of continuous suspense. But not too fast, lest we stumble on the wrong conclusion: to assume that Sheehan means her music is somehow horror-pilled misreads her interest in Aster. The influence has absolutely nothing to do with hairy necks.

It has to do with heads.

(Not literally, of course, but formally.)

Three female characters and one bird lose their corporeal heads in the course of “Hereditary”; both a mother and her son slam theirs violently, repeatedly against surfaces which give not an inch in return; and shot after cinematic shot (what is a close-up if not a cutting-off?) fixates on the plastic contortions of that which swivels dangerously upon very fragile necks. While many commentators have remarked on the film’s now-famous ending spectacle—its rearrangement of three feminine generations in a prostrated, headless hemisphere—decapitation rarely figures in readings of the film as anything other than either a visual obsession of Aster’s or a simple manifestation of metaphoric themes (loss of head as loss of control; cutting off one’s head as ultimate abreaction). The critic Michael Koresky’s summation of the movie in Film Comment stands neatly in for the film’s mainstay interpretations when he calls it “an entirely discomfiting portrait of [familial] dysfunction, in which the mysterious past, chaotic present, and unsure future of one domestic clan are in constant, fractured dialogue, and where the stakes are absurdly high.” “Hereditary” is, these readings figure, a family drama on paranormal steroids, forever (mis)taking all the content for the form and leaving heads, like Charlie’s left by her brother, lying rotting, heavy, bloody where they fall. Criticism has so far refused to admit even the possibility—gruesome as it may be—of a generative acephaly: a productive losing of one’s head.

But what if, just for a moment, we set aside the obvious assumption that loss of head be merely undesirable. We might, then, for instance, notice in Leonard Bloomfield’s 1933 book Language a syntactic form, later lifted into generative morphology by Chomsky, called an exocentric construction, colloquially referred to as a headless form. According to Bloomfield, headless forms are semantic collections (think a clause or sentence) in which no solitary word performs the bulk of phrasal signification. These constructions lack a “head,” a highest-order unit on which to pile meaning; no element can be made out as syntactically equivalent to the whole (as in “the soft thud of her severed head”). Headless/exocentric constructions are contrasted with endocentric ones (what M.A.K. Halliday tellingly refers to as “bloated words”): there, a sole unit—usually a noun—contains much or all semantic thrust (“flesh” in “charred paternal flesh”). Headless forms, on the other hand, have no such governance: “The resultant phrase,” Bloomfield writes, “has a function different from the function of any constituent.” As a form of catalexis, sentential headlessness is what is structurally lacking (missing a “head”) but semantically gaining (meaning is accrued, non-divisible, cumulative): the syntactic equivalent of “greater than the sum of its parts.”

And so, as any aghast post-credit viewer of “Hereditary” can tell you, what matters most in headless forms is how they end. The form’s stop, in whatever manner it arrives, is the sole designate of totality and significance necessary to figure it as exocentric at all (so long as it is ongoing there remains the possibility that this or the next unit will turn out to be the head; only having reached a punctuating limit can we admit to knowing otherwise). Headless forms require that we live through their entire duration. There is no crux, no sequence more structurally weighted or formally determinate than any other, no point except the end at which we can say, “I know how this will end.” It is through such an even distribution of signifying weight that “Hereditary” reconfigures acephaly not as thematic content (metaphoric, affective) but as form itself. It is not, we learn too late, a film in which the outcome could ever have been altered by better or more responsibly affected reactions under traumatic circumstances: there is no analysis in which one or another scene, shot, or choice figures as turning point or giveaway. On the contrary, everything has gone evenly, equally, exactly according to plan, and the final glory in the treehouse is the unforeseen reward of all cogs turning smoothly in their predetermined role. The film, then, does not invite spectatorial empathy with the ever-growing threat of losing one’s head; quite the opposite, “Hereditary” is a film determined at every moment to be headless.

Which brings us back to Sheehan.

(As if she ever left.)

Sheehan values “Hereditary” as a hermeneutic tool almost exclusively for the film’s achievement of retrospective inevitability, the hindsight awareness that all of this was already in motion and there was never any other possible ending and the scale was so much larger than I ever could have imagined. Likewise in her music, emergence joins with immanence to drag sound into a volatile state of permanent discovery where “the piece” exists as a just-beyond-reach horizon, never accessible in advance of its experience and constantly subject to discovery. Which is not to say it’s improvised—Sheehan is incredibly particular about sound qualities, organization, rates, and contingencies—but execution and accuracy is only half the battle. Like “Hereditary,” where the individual participants (mother, father, daughter, son) remain in constant reaction to some larger force they sense is on the move but cannot view in its entirety, players in her music must submit (it demands humility) to the invisible. In place of “pure” metrics—like meter, notes, and rhythms—eyes, ears, heartbeat, and skin are forced to account for the invocation of a form they cannot see in a place where no pulse is ever given but where time moves absolutely and ceaselessly on. Which puts odd pressure onto her scores: notation is, understandably, a paltry approximation for that dawning sense of some huge, plastic shape being spun out of thin air.

“I can’t notate intuition,” Sheehan says. “My notation comes from the absence of the luxury of time. It’s a compromise: How can I get ideas across without fixing too much to the page? If it looks perfect on the page, there might be no questions. I could fix every parameter, but that would kill the summoning. What facilitates my music is the questioning of it. I could be highly exacting, but then performers think the music is exact, which creates a disconnect when we’re in the room together. Because while the sounds are very specific and necessary, the ways to get there are necessarily various and contingent. The performers have to spend time exploring the form outside of my notation.”

The piece, in other words, cannot be sufficiently contained within the object of the score. Physical notation is only a set of coordinated and minimal instructions, a guardrail for pace and sound whose actualization depends entirely on the players’ real-time decisions in reaction to the resultant present. Perceptible pulse is, likewise, an entirely absent phenomenon, because her sounds gestate at an internal, non-metric rate that never satisfactorily obeys external impulses. Performers must rely on a sensation of becoming to guide what takes place without (the toughest part) communicating the planning of it to the audience. To get that effect of spontaneity and discovery, Sheehan’s scores are deceptively barren, simplistic even. Often, she says, players assume her work is easy. But a successful performance of her music requires complete and utter physical commitment to the absolute volatility of the present suggested but not prescribed by her scores. Players have to know it, inside and out. And that, she says, usually requires collaboration.

“We need to get off the page as soon as possible and go back to the material of the instrument,” she says. “My music is feedback, it’s dependent on how many bodies are in the room, who’s in the room, the shape of the room… you can never calculate those things ahead of time. When I rehearse ‘Talk Circus,’ it’s one of the first things I say. If I write ‘Turn to Dial 9,’ that’s only a suggestion for a certain quality of intensity. You have to fish for it, and the actual number may change by the day. But the more you get comfortable with the object, you will be able to find it, you’ll gain intuition, and eventually it will become natural.”

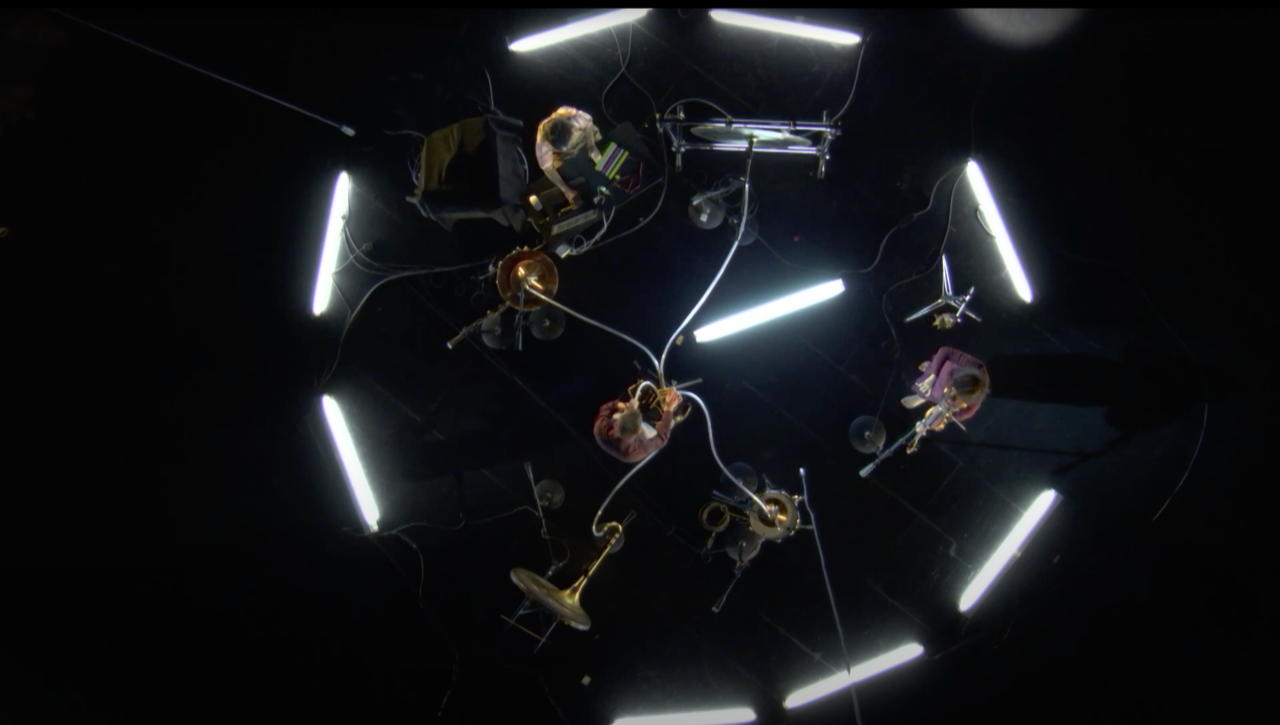

The primary challenge to that intuition—and the reason she prefers in-person collaboration over hermetic, distant composition—is the arsenal of lo-fi machines that run rampant through her scores. Alongside standard Western instruments are a host of hand-made, hybrid technologies that require extra time to feel out. Most famous among her toys is the No-Input Mixer, a source-less electronic feedback system pioneered by Toshimaru Nakamura in which a mixing board is made to “speak” all by its lonesome by looping its noisy static back into its input. The NiM’s presence in her music has a special, formal significance: a simple, “mute” object is being coaxed into outsized articulation by some invisible magic. The mixer received its fullest excavation in her “Talk Circus,” an electrifying percussion duo that remains one of her most performed works to date; the last decade of the instrument’s ubiquity in electronic music circles owes much of its origin to that piece. But the NiM is one of many for Sheehan: there’s also the hypnotic maze-toy-turned-circuit at the center of “Circle Speak”; the metal-sheet-mechanism in “consumed; teeth shut”; or, most recently, a serpentine brass-percussion monstrosity constructed at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center in New York for her “The Transfer.” Sheehan puts as much time into understanding her machines as into her scores; many of them she builds by hand. (On my visit to her verdant composing shed in Northampton, Massachusetts, a host of tape-decks are in disarray across the floor, waiting to be soldered into some new hybrid instrument.)

But her attachment to technology does not extend to autogamy; “fixed media”—any autonomous layer of electronic sound—is a foreign concept in her work. Her local machines always require human actants to coerce them into sound: they are instruments to be played, an important distinction. Because it’s in the resultant circuit of manipulation, the feedback loop of information between performer and unruly object, that her real “machines” emerge. According to Sheehan, her handheld, DIY machines are only crude tools for summoning the global, invisible “machines” that gradually coalesce in the collective interactions between performer and instrument, performer and performer, and performer and form. The real machine is what is erected by collective participation, what comes into being, haphazard and fragile, by the contract and contact of the assembled, decentralized networks of coordinated body-instruments. These machines are built by sound in real time, non-reducible or analyzable, and available to perception only in the posterior totality of the lived-through experience: they’re headless forms.

A mother to a son:

“If [grief] could’ve maybe brought us together, or something, if you could’ve just said ‘I’m sorry’ or faced up to what happened, maybe then we could do something with this!”

(Feeling here being what alters the outcome not enough)

What is so apposite about “Hereditary” in the context of Kelley Sheehan is precisely the manner in which such forms act into affect to ultimately reconfigure feeling as entirely extraneous to the system. In any other context, the film’s closing sequence would present as worst-case outcome: the complete termination of the family unit, the triumph of evil, the unleashing of a devil on Earth. The “bad side” wins; “Hereditary” actualizes the hypothetical ending on which spectatorial suspense is always predicated but that so rarely comes to be (one survivor always left to ensure the return of good, if not the threat of a sequel). In context, however, Paimon arrives in a coruscated sequence of gold and pealing brass whose glory reveals only too late the invisible operation that has been in constant motion since the first. All the screams of the family drama were quite literally overflow, useless affective leakage from this blisteringly effective execution of order. On a rewatch (the movie demands it), one takes more notice of how, accordingly, the camera never lingers with mourning, with fear, nor even with the bodies of its dead. The camera does not empathize. It presses on, continuing to cut off at the hairy neck all those who would seek to install small-time family values on its grand scale. Likewise in Sheehan’s music: “harsh” or “industrial” electroacoustic noise is ultimately placed in service of the formally rapturous and transcendent, revealing the transient irrelevance of a momentary “feeling.” Also likewise: it’s not until the ending that you know that.

Take Sheehan’s “The Bends.” Written in 2021 for 11 members of New York’s [Switch~Ensemble], the score asks each of the musicians to operate an independent “sound field” centered predominantly around the displaced cone of a dismantled speaker system (another favorite lowercase-m machine of Sheehan’s). That cone, once the passive medium by which sound was transmitted, is refigured as an active instrument itself and made audibly responsive to all manner of touch, vibration, pressure, angle, and intensity. Manipulating the atmosphere around these strange non-teleologic antennae through an array of household objects in tandem with their Western classical instruments, the players draw dense and variegated bands of noise as if from nothing. Their acoustic instruments, shuddering under immense force, join and melt into this seamless, mass gestating body.

Thirteen minutes in, however, and just before the end: silence. Like the twin vacuums of room noise that frame the work’s dead center, this emptiness remains pregnant with a sense of propulsion: silence is never figured as respite or terminus in Sheehan’s music, never as a starting-again or a breath of release but merely as the absence of sound which threatens to return again at any moment. This time, though, the work undergoes a telescopic dilation akin to the twist in “Hereditary”: what happens here reframes the whole of what came before. And it all hinges on a cheap handheld fan.

There’s a soft click, a human cutting into weighted silence to set the fan in motion, followed by the audible whir of blades which, in turn, gently activate the speaker cone and summon (as if by magic) a low electric growl. The process is repeated in slight variation in the circuit’s termination: switch off, end growl, slow-to-stop of blades. The trick is repeated a few times more at varying speeds, almost threatening to begin some new section, only to disappear as soon as it arrived, this time for good. It lasts no longer than a minute.

Out of context, this lo-fi triode—body, fan, cone—is a satisfying but utterly unremarkable sound. But as the vested nexus of arrival for an immense 11-body unfurling, this tiny, local circuit of intermittent activity is temporarily imbued with an outsized, luminous presence that, appropriately, far exceeds its impoverished (mundane, misused) means. It doesn’t sound big, per se, this is not a question of decibels; what we hear is presence, an impossible simultaneity. Until now, the cones have functioned as a kind of sonic given, too saturating and omnipresent to properly note their source. Here, however, both input and output are laid bare, the feedback loop made audible on all ends of the equation. We hear the cone react to the fan; we hear the human respond to the cone; and we hear in all three—unconcealed for the first time—the responsive and dexterous chiaroscuro within what previously appeared as grueling darkness. The cone has, at the last second, transferred a share of its magic to the intermediating objects, resulting in a complex sound at last understood both for what it merely is and as greater than the sum of its parts.

Sheehan’s handheld fan thus becomes the musical analogue to what José Esteban Muñoz in Cruising Utopia sees in Andy Warhol’s Coke-bottle-as-vase: “Everyday material … represented in a different frame, laying bare its aesthetic dimension and the potentiality it represents. In its everyday manifestation, such an object would represent the alienated production, consumption, and labor that is the realm of the performance principle. But for Warhol [and, we might add, for Sheehan]… the utopian exists in the everyday, and through an aesthetic practice I am calling queer, the aesthetic endeavor that reveals the inherent utopian possibility is always in the horizon.” One cannot begin listening to “The Bends” at the end and expect the triode to have the same effect, just as one cannot begin watching “Hereditary” in the last five minutes and comprehend the awesome horror of such resplendent, devastating wonder. It is only by the lived-through durational commitment to an accumulating, headless form that utopia and the potentiality inherent to it is permitted to congeal around otherwise banal objects. To discover utopia in the sound of a fan is to momentarily access a field of speculative alterity, a there that is not here in which cheap toys are as much instrument as tool—only to have it vanish over the horizon in the same instant.

Attending to Kelley Sheehan’s music—as either performer or listener, it matters little which—demands a devotion to an impossibly large form that one will never know in full but commits to anyway for the guarantee-less promise that possibly, potentially, the present might shift enough to peek beyond this crude and hybrid here and now. If all goes right, all these imperfect human participants and strange, half-broken machines will transform into an alternative whole, a machine held together, even if temporarily, by nothing more than a collective commitment to be so. Such steadfast commitment to speculative potential is the work of utopia: something that cannot rationally survive in this impoverished world is being set in future motion by the music. Like “Hereditary,” Sheehan’s music teaches us to relinquish our affective jolts and look instead for immanence, for push, for the encroachment at every moment of something else, something more that is not yet here but may soon be. There is no small amount of imagination involved in such a music. It asks a listener to hear towards invisibilities, peripheries, to forms outside itself. But the reward of doing so, of lingering too long within it, is to see in the flash of a vanishing moment another world than this one.

This—what it cannot see but strives toward—is her music’s utopia.

(Or: what these parentheses have been:

this register astride that is not in but on, near, alongside:

her forms, her machines are somewhere parenthetical:

close at hand but never visible, hidden but bearing down, unrecognizable until the last moment

when it is always already too late

and then—) ¶