Watching a Yorgos Lanthimos film invariably leads to esoteric questions. Via “Dogtooth”: Why are you calling an armchair a “sea”? From “The Lobster”: If you had to be irreversibly changed into an animal, which one would you pick? And, thanks to Lanthimos’s new short, “Bleat,” co-commissioned by the Greek National Opera and cultural nonprofit NEON: Does a dead body still produce saliva? (Another question, posed to the film’s star, Emma Stone, at an Athens press conference on May 5: “Can cannibalism, death, and passion all exist under the same umbrella?”)

Most of these questions make sense in the moment (though I sympathized with Stone’s confusion over the question of cannibalism, a theme that doesn’t explicitly factor into “Bleat”). Lanthimos’s films take place in controlling worlds buttressed by highly specific, yet often-unspoken, rules. In “Dogtooth,” seen as a metaphor for everything from Nazi-era eugenics to Stranger Danger, a father keeps his three children isolated in an Eden-like villa, optimized for peak performance in every way except for their total inability to engage with the outside world. In “The Lobster,” couples must be paired off according to at least one shared characteristic, or be turned into an animal of their choosing. The world of “The Favourite,” Lanthimos’s period film about Queen Anne that looks like a Les Arts Florissants opera, is governed by court protocol both spoken and unspoken.

The drama of these films comes out of the character or characters who seem poised to upset the rules of the game. These characters are rarely afforded any more backstory than their peers—it’s what they do versus who they are that upsets the fulcrum. When Olivia Colman’s Queen Anne tells Emma Stone’s Abigail, “You are a dear person,” in the thick of Abigail’s upwardly-mobile scheming to become a noblewoman once again, it’s clear that character and action exist at cross-purposes. Lanthimos cleaves to his compatriot Aristotle’s notion of tragedy as not being an imitation of people, but of action: “Well-being and ill-being reside in action, and the goal of life is an activity, not a quality.”

“Bleat” takes Lanthimos’s conceptual architecture and Aristotle’s foundational theory on drama to greater heights. We know next to nothing of the nameless main characters’ backstories, and are left to guess at their relationships. The world of the 30-minute film is governed by tradition, events, and actions. There are also specific rules for how it is to be screened: only on 35mm, and only with live musical accompaniment. This in an age where, especially over the last two years, half-watching a new release on your phone while doing three other things has become the norm.

Lanthimos’s work is the second of its kind in a series called “The Artist on the Composer,” produced by NEON and the GNO (disclosure: the latter covered my flight and hotel to attend the premiere of “Bleat” in Athens), whose aim is to commission new works by artists and filmmakers that incorporate live orchestral music. The intended result is an interdisciplinary, intergenerational dialogue that reimagines the potential of opera “free from every standard operatic convention, trope, and storyline.”

In some ways, “Bleat”—a silent black-and-white film that owes much to the psychologically-revealing close-ups of Tarkovsky and Bergman and plays out over the music of Toshio Hosokawa and Bach via Norwegian composer Knut Nystedt—achieves this objective. Very few operas rely on film to tell the story, and even fewer get away with a sub-verbal libretto. Since the 17th century, the genre has relied on arias as vehicles to convey emotional states, backstory, and motivation, allowing the action of the piece to stand still so that audiences can catch up with the character’s internal state. At face value, the strongest connection “Bleat” seems to have to opera is that it was co-commissioned by an opera company, and premiered in an opera house.

Taking Lanthimos at face-value, however, entirely misses the point. “It doesn’t fit into the form of film production,” GNO Artistic Director Giorgos Koumendakis said of “Bleat” at the same press conference earlier this month. He sees the film as having two scripts: the screenplay written by Lanthimos, and a script determined by the music, which Lanthimos chose as he was writing the film. This sets “Bleat” apart from traditional films where music is determined much later on in production. It calls to mind something director Miloš Forman said when working on the screenplay for “Amadeus” with playwright Peter Shaffer: The music is the third character.

In his treatise on opera, The Impossible Art, composer Matthew Aucoin writes: “Opera’s basic ingredients are among the most primal human needs: song and narrative. By combining the two, opera gives voice to sensations that are either too raw or too subliminal for words alone, and incarnates them in specific individuals…in a way that music on its own cannot. It is a fusion of the too-big and the too-small, the unnamable and the named.” In this sense, “Bleat” is manifestly an opera, stripped down to its most primal elements. Lanthimos’s screenplay offers us a narrative, as simple as it is intricate, and the music of Hosokawa and Nystedt provide the song (including vocals, thanks to Nystedt’s choral arrangement of Bach’s “Komm, süßer Tod”).

In the film, there is no shortage of the unnamable, the raw, and the subliminal. Shot on the Greek island of Tinos in February 2020, “Bleat” ostensibly begins with a funeral. In an isolated home on the island, Emma Stone sits, well, stone-faced, surrounded in silence by guests. Her eyes convey the sense of being both acutely alert and utterly drained. Shots of the men and women gathered at her house, who are played by non-acting Tinos residents, convey similar depths of inexpressible emotion. As the audience, we’re able to superimpose any number of backstories, emotions, and motivations. There’s the familiar discomfort that comes with a moment of silence or in sitting shiva, paid off when we see the corpse of French actor Damien Bonnard shrouded in the other room.

This isn’t a scene about Lear-ian grief or chest-banging loss. There are none of the grand crescendi of a Verdi or Puccini finale. Hosokawa’s chamber ensemble piece “Singing Garden,” the sort of work that epitomizes what Aucoin describes as the “liberating uncertainty” unleashed by the best of operas, blends the epic and the mundane, recreating the vacuum that’s often felt in the wake of loss. Stone does cry, after ritualistically kissing the hand of every mourner as they leave. But, as day turns into night, she spends a lot more time voraciously tearing into the food left by her guests—artichokes glistening under a patina of olive oil—and peeling off her layers of black wool in order to mount Bonnard’s corpse.

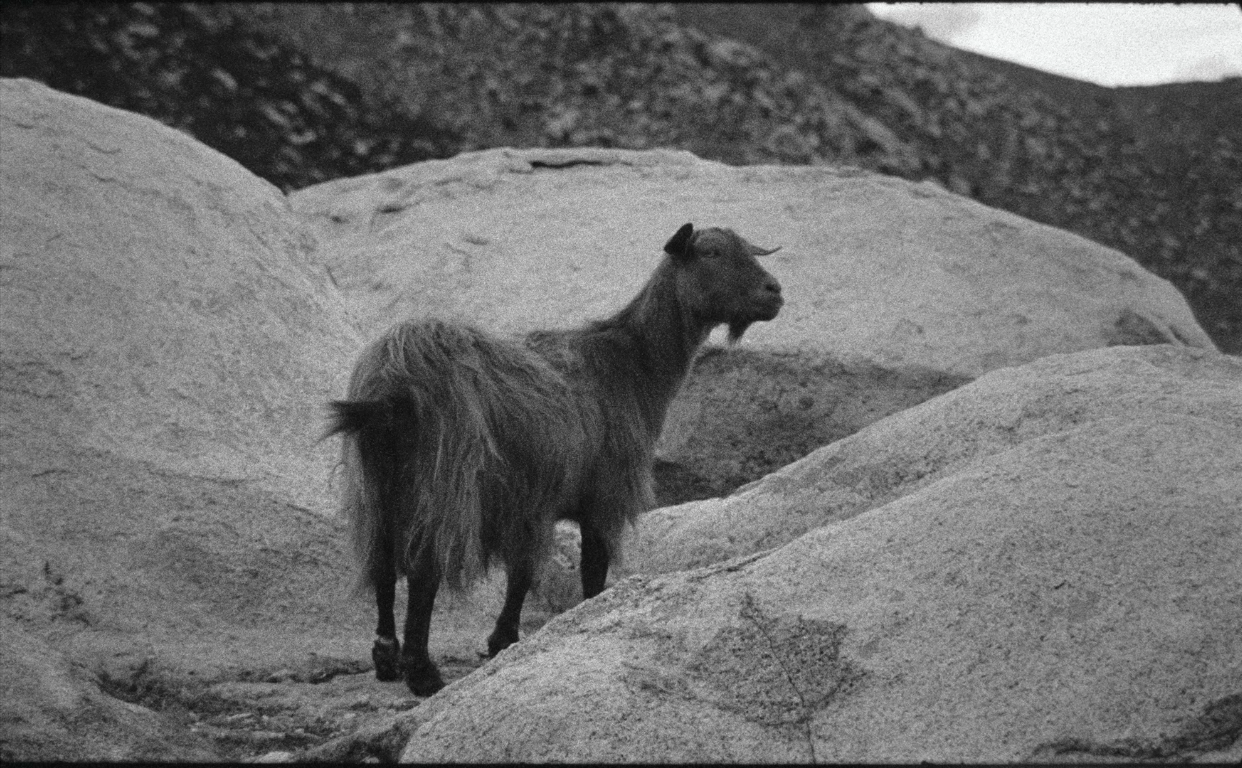

In the next scene, paired with the even sparser tones of Hosokawa’s “Nachtmusik” for solo cimbalom, Bonnard and Stone trade off. It’s now night, and Bonnard is the one to wake from their post-coital heap, don Stone’s black robe of morning, and wrap her corpse in his own white shroud. Much like the sensualism of the previous scene, what stands out here is not so much the actions that take place—the burial of Stone’s body, a funeral dance, the sacrifice of a goat that leads to the consumption of a hearty stew—but the synesthetic impulses that these images evoke. You can feel the crumbs of dirt that pelt Stone’s cheek. Over the hammered cimbalom notes, you can hear Bonnard’s shoes grind on the earth as he dances himself into a subdued Dionysiac frenzy. The sinews of the goat’s meat get stuck in your teeth.

Incubated in the Zen-like folds of Hosokawa’s compositions (no emotion, just observation), these moments are the opposite of grand emotional revelations. Even the burial is quotidien: no baby thrown into a fire, no body stuffed into a sack, no nuns lined up at the guillotine. The austerity of the medium nevertheless brings us to a visceral sensory overload that ignites in the final scene: Nystedt’s Bach chorale emerges out of the silence as dawn breaks once again. Emma Stone walks back to her home, wrapped in the white shroud, finds Bonnard’s body on the bed, and once again they trade places. Pale winter light cuts through the windows of the house, and the mourners from the first scene are outside, all dancing as an act of ritual mourning. The resolution of the Bach allows us to feel every fiber of the uncertainty that the film evokes.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Lanthimos has never directed an opera, although he would welcome the opportunity. But, as antithetical as “Bleat” seems to the well-worn tropes—no clichéd opera gestures or paternal revelations here—it also exemplifies many of the conventions and storylines integral to the roots of opera. It’s hard not to see parallels to Orpheus and Eurydice between Bonnard and Stone, who seem to be constantly chasing one another to the underworld, yet whose paths are set on a Möbius strip, never allowing them to see one another on the same plane of existence. It reminded me of what Missy Mazzoli said in an interview last year about death in opera being “a metaphor for many different kinds of things in our life that we don’t talk about.” The best way to talk about those things—heartbreak, rebirth, freedom, separation, ostracization—is to illustrate them in highly-dramatic representations.

This is a sentiment at the root of Greek tragedy; what Aristotle codified as “an imitation of an action that is admirable, complete and possesses magnitude; in language made pleasurable…effecting through pity and fear the purification of such emotions.” (Lanthimos denies any deliberate metaphors, but it’s also worth noting here that the Ancient Greek for “tragedy,” τραγῳδία, literally means “song of the goats.”) It was these same tragedies, along with myths and fables, that a group of Italian composers and poets turned to in the Renaissance, becoming the earliest midwives for opera. These artists hoped to discuss the undiscussable and name the unnamable, in hopes of inspiring in audiences a sense of emotional virtue and moral magnitude.

This affinity for the ancient comes up time and again through opera’s history, with many of the same characters and circumstances cycling through works by everyone from Mozart and Gluck to Wagner and Strauss. Even Aucoin’s Met debut was with his own adaptation of the Orpheus myth. 400 years later, we’re still in pursuit of what opera historian Stanley Sadie called “a stage music comparable in power and intensity to ancient tragedy,” or what composer Jacopo Peri described as “a harmony surpassing that of ordinary speech but falling so far below the melody of song as to take an intermediate form.”

By his own admission, Lanthimos has historically been wary of music in his films, and has yet to hire a composer to write a bespoke score for one of his projects. Yet the music that Lanthimos selects and works with seems related to the power Sadie speaks of, and the harmony that Peri pursued in some of the earliest operas. Of using Beethoven to heighten the dystopian world of “The Lobster,” Lanthimos told fellow filmmaker Peter Strickland in 2016: “I was trying to add something other than what the scene was doing itself, something that might even be in the exact opposite direction of the scene. Instead of reassuring the scene with a related kind of music, both of them together created something new, something that wasn’t there before.”

In “Bleat,” Lanthimos obliterates the comparison between stage music and tragedy by marrying the two elements. It’s a marriage of opposites, one whose harmonic dissonances surpass ordinary speech—they even render such speech superfluous. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.