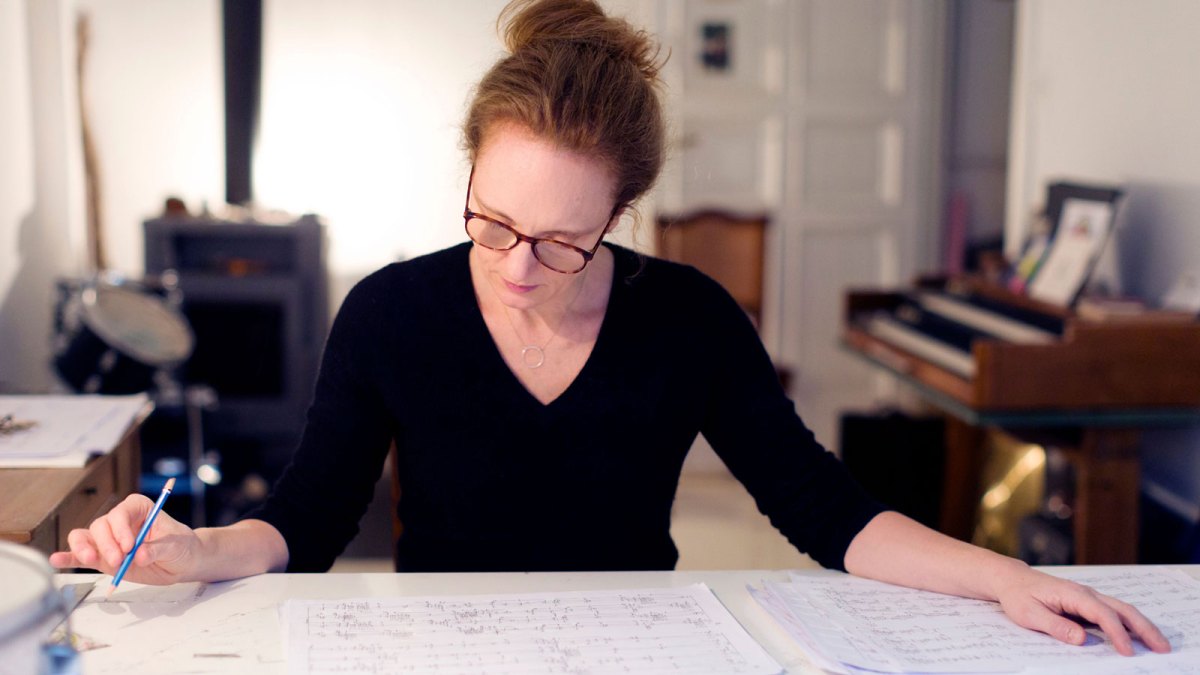

The composer Rebecca Saunders was not where I imagined her to be. Plans for a meeting in person were moved online, owing to her retreat to the countryside to complete a deadline. So it was a surprise when Saunders appeared, not in some remote rural studio, but in her Berlin flat.

“I think a lot of people are having a hard winter,” she said. Saunders hasn’t been well, a mixture of bronchitis and long Covid meaning reduced traveling, a few weeks staying well away from people, and the rare extension to a deadline. Yet she was in good spirits—or at least seemed it. Saunders has mastered that skill young radio presenters are encouraged to develop: By smiling into the microphone, even her most barbed comments sound aurally pleasant. When, in the closing moments of the interview, I asked how she used the €250,000 that accompanied the Ernst von Siemens Musikpreis she received in 2019, Saunders replied that she wouldn’t be answering questions around “turbo-capitalism.” “I bought a sports car!” she said with bright-eyed sarcasm, and departed the call soon after.

By that point, we had spoken for an hour, pausing only to jump across Zoom links and for Saunders to give her cooking a stir. We discussed spaces, embodied sound, her new release on NMC, and recent developments in the UK music scene.

VAN: From previous interviews, it seems that being in the city is an important part of what you do. So the idea of going to the countryside seems like quite a change…

Rebecca Saunders: Yes, but it’s interesting to go somewhere else during the creative process, just to place yourself in a different environment. I think you’re firmly anchored in reality when you’re writing and working creatively, but it’s sometimes quite useful just to disappear for a couple of weeks, to go somewhere where there’s no internet. It’s really refreshing not to be able to look at your phone.

Is there a compositional reason for moving to the countryside? I guess there’s a different silence there.

No, I wouldn’t say so. Sometimes it’s very important to take oneself out of a known environment, to get offline and to be unreachable. It is refreshing and extraordinary to be in the country and to experience how incredibly noisy it is, how early you’re woken up, how loud the birds are, and how you begin to behave differently. You go to bed earlier, you live a different kind of life. It’s interesting, but it’s not the life I would like to live on a permanent basis.

Your titles are often followed by multiple definitions—“void” is accompanied by three dictionary definitions, “Skin” two. Do you do that to invite multiple, potentially conflicting interpretations of your pieces?

If we take “Skin” for example, it was one of these rare pieces where the title was actually determined before I started the piece. I was very interested in contemplating the surface, what is beneath the skin of sound, or beneath the skin of everyday reality. The word “skin” I thought was wonderful, because it’s so multifaceted; there are so many different meanings, but they’re also closely intertwined with each other. I like these words which are both a noun and a verb, for example; that triggers a lot of associations. And whether you see skin as a metaphor for… god, what’s Vergänglichkeit?

My German isn’t great.

Sorry, I’m still a little bit COVID-ed… Transience! The concept of transience. Or, to contemplate the surface of the skin and its sensuality, and consider touching the skin, tracing the skin… [The word] implies all different kinds of interesting ideas which fascinate me.

Why did you decide to pair “Skin” with “void” and “Unbreathed” on the NMC album?

I think they fit well. The idea of having a soloist, in some form or another, is really important for me. But then, on the other hand, “Skin” isn’t really about a solo soprano and an ensemble, the voice is embedded in the ensemble. [“Unbreathed,” meanwhile, is for string quartet.—Ed.] So there are different manifestations of what a soloist could be, and the relationship between the soloists and the main body of sound.

In the British press, introductions to “the British-born, Berlin-based composer Rebecca Saunders” often come with an extra clause (implied or otherwise) along the lines of “whose music should be performed here more often.” How do you feel about that?

I’m just super happy that there are some great musical bodies, people and soloists who do like to play my music. In Huddersfield, they’ve worked their way through a lot of my music. I had a great concert with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, where they did “to an utterance.” I had a portrait concert at [Southbank Centre’s] SoundState.

What art means is very, very different in Britain from what it means “on the continent,” or what we used to call “on the continent,” which is now just Europe… I think generally, there’s a certain misunderstanding that music is about telling you something, it’s about something, and it’s not that. There isn’t some strange, intellectual hierarchy that we’re marking here; it’s not about the listener having to understand. It’s about culturing an environment of curiosity, and letting the music actually touch you. I think my music can be very direct and very emotional, apparently. [Laughs.]

I really don’t feel I have the right to be annoyed [though], I’ve had enormous opportunities elsewhere, I’m happy, I can do my work and I am content… But I miss it. I would love to engage much more with British culture.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

In the past month, with changes in Arts Council England’s funding structure, it feels like the ground has fundamentally shifted for artists.

I would really love to question this whole ethos, because it’s crazy. When one talks about creating a music which is more accessible, you’re creating an artificial hierarchy, which is saying, “I have something to tell you, I tell you how to listen, I tell you how to think about this.” Art has an extraordinarily important function in society, but it’s not about telling us how to think and how to feel. It’s about providing spaces for those thoughts, those ideas, those concepts, which don’t fit into everyday life.

It presents you with the unexpected and creates a space for us to be curious and tolerant towards the other. And it’s this diversity which is so important in art. You can’t say there’s only one way to understand—it’s almost communist, you know. The whole thing is ridiculous, to create music which only can be understood via points A, B, C, and D.

The whole thing [regarding English National Opera] is incredibly patronizing. It’s extraordinary that no one’s actually pulling [Arts Council England] up on this and actually saying, “Who the hell do you think you are? Who are you to define what art is?”

On Twitter, Thomas Adés recently compared ACE’s Darren Henley to Stalin.

Mmm. Yeah, I’d go along with that. I think one should be critical, and that’s the whole problem. I’m not talking about cancel culture; that’s something completely different, so let’s not mix things up. But if you’re creating an artistic environment where there are things that an artist is not allowed to say, you have a massive problem with your democracy.

In particular, contemporary music is being reduced by the cuts.

I mean, contemporary music is experimental. We’re meant to be trying things out which people haven’t heard before. We require an atmosphere of curiosity, tolerance, openness, so that we can grow, think, and feel. This intolerance is really dangerous, and blanking out of this [artistic] diversity in the name of one kind of diversity—and I’m not arguing about that, I think it’s fucking brilliant—you’ve got to be very, very careful.

[“I just have to go and stir the sauce,” Saunders says right on cue.]

You work a lot with spaces. Does your inner ear have a default room?

It has changed over the years. When I was very much younger, I used to imagine the space where a piece would first be played. I found it quite inspiring to imagine the empty space, the empty stage, and the performer just before the sound is made.

Different experiences [with spatial polyphony] have changed my inner ear. I wrote a series of many solos one after another, and then returning to an ensemble piece without a voice or soloist, I suddenly realized I was listening and thinking in a different way. I had a few new synapses—I could really feel my brain expanding, humming.

In your spatial pieces, you’re interested in the physicality of the listening experience. How do you go about translating that onto a CD?

A CD is an object, a thing; that’s unusual for us, isn’t it? We’re working in a métier where we don’t actually make a thing. What we make is something completely transient. I write an abstract, which is interpreted, and then it’s fleeting, and it’s gone, something which is very difficult for us to deal with in a consumer-oriented society.

But I see these objects as wonderful things. And you curate a CD, you choose the pieces, you decide on the order, you master them so they have similar acoustic environments. It’s a different project, I think it’s very special. But it doesn’t replace the live listening experience.

When you burrow into sounds to find their essence, where do you imagine that essence is located? And is that place embodied?

It’s a bit hard to answer that. One of the really refreshing and fascinating parts of the process of writing “Skin” was to be working with a voice, where the embodiment of sound is so obvious: A voice does not exist without the body. You can take that way of thinking about music and apply it equally to a performer using an instrument—it’s the act of the embodiment of sound. With “void,” I wrote for percussionists Christian Dierstein and Dirk Rothbrust and their embodiment of sound. I found it fascinating to take their very personal instruments, and to give them to each other, so somebody else was embodying somebody else’s sound.

Your scores are closely connected to individual performers—take “void,” “Skin,” or “Blaauw,” for trumpeter Marco Blaauw. Could you imagine them in different hands, and how does that change your music?

I actually recently rewrote “Blaauw” for single-bell trumpet, because I worked with Saba [Stoianov]. He comes from Bulgaria, and has a very different tradition. He plays very differently, he has a very difficult physical way of playing and a very different color. The perspective changes the light shone on the object.

I want, and know, that a piece has to be played by somebody else, and that’s fascinating knowing it will be completely different. Every time a piece is played with a different conductor, it’ll be a completely different piece, and that’s so exciting. A different hall, a different acoustic, a different temperature, a different humidity… always different. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.