English National Opera: Coming to an as-yet-undisclosed location near you. Arts Council England’s decision to strip ENO of its subsidy in the latest round of funding has been a shock to the arts ecosystem in the UK. As Hugh Morris wrote in VAN last week, the approach of ACE appears to be: Fuck around and find out.

ENO could move to another city, like Manchester, or become a touring company. Which I’m sure will delight the hundreds of musicians, stage crew, and back-of-house professionals who work there and live in and around London. Perhaps the Arts Council will use the money saved to invest in some new headphones for their Chair Nicholas Serota, who, when questioned about ACE’s chaotic treatment of the company on the BBC, complained that he couldn’t hear what he was being asked. I sympathize with the advice composer Thomas Adès gave to the ACE leadership via Twitter: “Resign and get help.”

The situation is evolving. There has been an outpouring of support across the industry that appears to have had some cut-through into the wider media culture. Stuart Murphy, CEO of the company, managed to secure a meeting with the Secretary of State for Culture, Media, and Sport, Michelle Donelan.

ENO’s future is uncertain; its past is rich. The company was established in 1931 by Lilian Baylis, manager of the Old Vic and Sadler’s Wells theaters in London. She had staged opera at the Old Vic in an effort to bring a different audience to the art form. The Sadler’s Wells Opera Company set up shop in Clerkenwell and toured nationally; it became English National Opera after moving to the London Coliseum in the 1970s. Baylis gives ENO’s extensive educational program its name. This achieved international recognition for ENO Breathe during the pandemic, which brought operatic breathing techniques to long COVID patients.

The name “English” describes a geographical and linguistic remit. The company has always performed opera in English translation, and championed work originally written in English. In 1945, ENO was responsible for the creation and premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “Peter Grimes,” a work that launched his career as an opera composer and re-launched opera in English—in sad abeyance since, well, Purcell. Since then, ENO has been a keen advocate for new work in English, including pieces by John Adams, Philip Glass, Nico Muhly, Tansy Davies, and Julian Anderson. This season sees premieres of works by Jake Heggie and Jeanine Tesori.

Giuseppe Verdi: “Rigoletto” (dir. Jonathan Miller)

Jonathan Miller’s production of “Rigoletto” came from the so-called “power years” of the company in the 1980s. It is now 40 years old and has been revived 13 times. His staging was innovative in its time and hard to beat now. The setting is Rat Pack meets “The Godfather”: slicked-back Mafia wise guys representing the indiscriminate brutality and wealth of Verdi’s Mantuan court.

The idea, so the story goes, came from a scene in “Some Like It Hot”:

MULLIGAN: Say, Maestro—where were you at three o’clock on St. Valentine’s Day?

SPATS: Me? I was at “Rigoletto.”

MULLIGAN: What’s his first name? And where does he live?

SPATS: That’s an opera, you ignoramus.

In Act III of Miller’s production, one moment stands out especially: The Duke flirts with Maddalena in a bar straight out of Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks.” He puts a quarter in the jukebox (the Duke Box, if you will—as shallow and changeable as he is!). The opening music of “La donna è mobile” starts up. But when the silent bar comes—one of Verdi’s great silences—the Duke impatiently walks back to the machine and gives it a whack to start it up again. Iconic.

Philip Glass: “Satyagraha” (dir. Phelim McDermott)

ENO has built an especially strong relationship with the work of Philip Glass, representative of their historical commitment to performing contemporary opera. The 2007 production of “Satyagraha” has regularly filled the Coliseum since its premiere (no mean feat for the biggest theater in the West End). It also makes an unusual exception to ENO’s strict policy of performing everything in English, sung as it is without surtitles and in Sanskrit.

This is not least due to the extraordinary work of the theater company Improbable and Phelim McDermott. As Glass’s pensive score unfolds, the most ordinary of materials are transformed by stagecraft into astounding visual spectacle. Sheets of newspaper undulate across the stage, forming a wall; they are bundled and ripped in a great writhing mass that seethes with revolutionary energy. In Act III, countless lengths of sticky tape are drawn painstakingly across the stage, before being pulled together to form a glistening, fragile figure that takes flight. This process takes 15 minutes.

McDermott and Improbable also partnered with ENO to produce Glass’s “The Perfect American,” on the death of Walt Disney. Also the gilded-nude-countertenor pharaonic circus-school extravaganza “Akhnaten” (AKA, “Poseurs and Monotheism”). Admittedly my partner left at the second interval of the latter because, as she put it, she “just couldn’t take any more fucking juggling.” The tap-dancing noses of Barrie Kosky notwithstanding, I can’t remember the last time I saw something like that at Covent Garden. (Simon McBurney’s “Magic Flute” with Complicité was another daring artistic raid on the standard repertory from ENO.)

Recently, I worked in a high school in east London. Because ENO introduced a policy of offering free tickets to people under 21, myself and two colleagues took 20 students to the opera. Not a single one had been before. I had secretly suspected that they would all hate it, and that going to “Satyagraha” was a terrible idea (it took the aforementioned partner to convince me). They were probably the most rapt I have seen an audience in an opera house in some years, and certainly much better behaved.

That is one of the things Arts Council England have defunded. Lilian Baylis founded ENO to provide opera for people who didn’t go to the theater in evening dress. That’s the legacy under threat.

Harrison Birtwistle: “The Mask of Orpheus” (dir. Daniel Kramer)

ENO is the only company to have ever fully-staged (twice) Harrison Birtwistle’s astonishing “The Mask of Orpheus.” The 1986 work is scored for a huge orchestra of woodwind, brass, and percussion, with electronics by Barry Anderson and an enigmatic libretto by Peter Zinovieff. The opera begins with the invention of language itself. What then unfolds is a tripartite telling or retelling of the Orpheus story, moving forward and backwards in time simultaneously.

In 2019, Daniel Kramer directed the second-ever staging of the work, conducted by Martyn Brabbins. It was an unreal, garish spectacle, wildly excessive in its deployment of dance, aerialists, and costume. Orpheus, sung tirelessly by Peter Hoare, was a washed-up rock star. The opera begins with a kind of ur-speech that tenor Hoare almost vomited across the stage as he climbed out of a primordial bathtub. One critic compared him to Rod Stewart.

The show’s unique look came from a partnership between designer Daniel Lismore and Swarovski, who studded the costumes with over 400,000 crystals. I loved it; a lot of people hated it (including, apparently, Birtwistle himself). But where else could you go to see something so bold, so outrageous… and so expensive? It takes subsidies to put on this kind of work.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “The Marriage of Figaro” (trans. Jeremy Sams)

I know a lot of opera-goers who balk at hearing opera in English. There are good reasons for this: inadequate placement of vowels in certain registers for singers, clunky translations that sound oafish for being too literal, the shocking revelation that actually all that stuff they’re singing in Italian might actually be quite prosaic and not smolderingly sexy.

But I’ve always suspected one of the more banal reasons behind this visceral dislike might be a peculiarly English petit bourgeois one: People like hearing opera in French and Italian in the same way that they are both impressed and intimidated by menus and nomenclature in foreign languages. They are the kind of people who feel special to be served an amuse-bouche or talked to about the cuissance of the steak au poivre.

Opera has always been performed in languages other than that of its original composition, and the preference for the latter is a relatively recent drift. What would one say to Handel, a German writing quasi-operatic oratorio using Italian conventions in London for foreign singers to perform?

But one of the jewels in ENO’s history is their longstanding relationship with translator, librettist, and composer Jeremy Sams, whose writing has furnished countless shows over the years. My favorite translation of his is “Figaro,” written first for ENO. Through several brilliant coup de lettres—if you will—it makes the argument for not just opera in English but the rejuvenating effect of translation on repertory works.

In the Act II finale, the gardener Antonio enters the scene with the commission Cherubino dropped when he jumped out of the window earlier on. An argument with Figaro ensues. In Sams’ version, recorded some years ago, Antonio is given a distinctive Geordie lilt (for non-UK readers, a Geordie is someone from the northeast of England, specifically Newcastle).

The translation is startlingly idiomatic. Highlights include Cherubino falling “on top of my hydrangea,” then “bugger[ing] off (and that’s begging your pardon).” “Well the man that I saw wasn’t riding.” complains Antonio to Figaro, “I’m sure I’d’ve noticed a horse.” Antonio is sure the chap who fell was taller: “Well,” the wily barber replies, “you always look small when you fall.” Susanna and the Countess can only groan in response.

W.S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan: “The Mikado” (dir. Jonathan Miller)

Two names sum up English operatic achievement in the 19th century: Gilbert and Sullivan. ENO’s partnership with Jonathan Miller produced yet another daring staging in the vein of “Rigoletto” when he set to work on “The Mikado.”

In 1987, Miller showed himself to be, if not exactly breathtakingly foresighted, then at least progressively-minded in restaging the wildly problematic Japonisme of its background and performance tradition. The setting draws on the Marx Brothers’ “Duck Soup,” high-kicking Busby Berkeley musical spectaculars, and the saccharine black-and-white melodramas of the 1930s to pull on the absurdist threads of the text and drama. One alarming sequence sees a troupe of decapitated corpses in dinner jackets dancing.

The original cast had Monty Python star Eric Idle as Ko-ko, and several future operatic heavyweights in lighter lyric roles, including Lesley Garrett and Susan Bullock. Felicity Palmer, before she was Dame Felicity, cuts a terrifyingly imperious dash as Katisha.

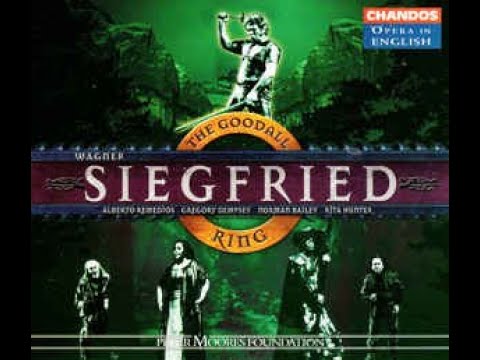

Richard Wagner: “The Ring of the Nibelung” (cond. Reginald Goodall)

It’s not all fun and games. Among ENO’s greatest achievements is surely their 1970s staging of the “Ring,” produced shortly after their move from Sadler’s Wells in Clerkenwell to the Frank Matcham-designed Coliseum in the West End. Andrew Porter’s translation itself decluttered Wagner’s rather clunky mythopoetics in favor of something immediate and idiomatic: a modernisation of Wagner just as radical as the Boulez-Chéreau Ring coming together in parallel at Bayreuth at the same time.

Several features of the production are remarkable. First is Reginald Goodall’s glacial conducting. Tempi are broad to an almost absurd degree. This should not work, but the score, in combination with the crispness of the delivery, moves with the inexorable character of tectonic plates. In his hands we hear and feel Wagner as emotional geology. Related to Goodall’s conducting is the remarkable clarity of the diction: He would, reportedly, spend years working with singers in the preparation of Wagner roles. The care lavished on every syllable is given space to be appreciated.

Also remarkable is the performance of tenor Alberto Remedios. Remedios does not quail in fear at Goodall’s punishingly slow tempi for singers. He also was so hardcore that in this “Ring” he sang both the roles of Siegmund and Siegfried consecutively. Imagine Jonas Kaufmann doing that.

Guiseppe Verdi: “La Traviata” (dir. Peter Konwitschny)

One of the reasons that ENO should remain in London is because there is only one other major opera house with a permanent presence in a capital city of ten million people. (This would presumably be a source of considerable embarrassment in mainland Europe, where Berlin, Vienna, and Paris all boast three operas of international repute.)

The Royal Opera House is a fine place and does its job very well indeed: expensive, starry-casts, very big and equally expensive dresses in splashy heritage productions, extensive private dining options for people who wish to recall their days at boarding school. But ENO has tended to offer productions that the ROH cannot, ones with a bit more vinegar than down the road in Covent Garden. “La traviata” is both a case in point and a study in contrast.

Richard Eyre’s production for the ROH is over 25 years old. It is a superb vehicle for singers who practice taking their curtain-calls in the mirror; the set is now so old that you can literally see it falling apart (watch from 2:00). Meanwhile, Peter Konwitschny’s production of the piece for ENO in 2013 cuts to the chase. He takes a knife to libretto and score, condensing the entire opera into one taut 90-minute span. The only furniture is a single chair; sets of theatrical drapes enlarge and diminish Violetta’s world. It is brisk, unfussy, and ferociously dramatic.

Giacomo Puccini: “La bohème” (2020)

Writing in the Guardian this week, ACE chief Darren Henley opined, with the oily tone of a KPMG consultant announcing a round of sackings, that opera had to change to survive. In what respect? What he called “grand opera” was too unwieldy and expensive, and opera would do better to find a new home in pubs and car parks. Meyerbeer? Buy a beer.

This must seem rather thin gruel to ENO staff, who, during the pandemic, actually did stage an opera in a car park: ENO Live and Drive created “La bohème” as a drive-in experience at Alexandra Palace in north London. That is, when they weren’t sewing surgical scrubs or using singing to help people suffering with long COVID. The “fresh thinking” Henley wants to impose on the company has always been there. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.