Today’s offer of investment from Arts Council [sic] of £17 million over the next three years will allow us to increase our national presence by creating a new base out of London, potentially in Manchester.” That last Friday’s public statement from English National Opera was spun by some as a successful outcome sums up the lack of clear-sightedness when it comes to the recent history of England’s national opera company. The facts as they actually appeared made for grim reading: ENO lost all of its annual £12.5m (about $14.2m) Arts Council England grant, which was replaced by £17m of “tailing-off” money, spread over a three-year period, to fund a relocation out of London. Another ENO statement on Wednesday confused the matter further: “It has become clear to us that [ACE’s] proposal needs urgent revision so we can continue to be a world-class opera company in London and perform more regularly in all parts of the country, including Manchester.” They certainly won’t go quietly.

In terms of sheer numbers (one of ACE’s favorite metrics), the biggest musical loser from Friday’s decisions on National Portfolio Organisation status was ENO, and the three words “potentially in Manchester” were a rather reckless way of conveying the news that an entire company, orchestra, and chorus might have to move over 200 miles north. (Chair of ACE Sir Nicholas Serota claimed on Friday that Manchester was actually one of several possibilities, reducing the prestige of ENO’s search for a new home to that of an itinerant sports franchise.) The ENO news is the biggest shift in a £24 million ($27.3 million) per-year reallocation of ACE funds outside of the capital at the behest of the government, with ACE giving sweeteners to London organizations willing to relocate.

As a refresher for those who have lost track of recent directions in UK policy, one of the key slogans of the Boris Johnson administration (two governments ago) was “leveling up,” an idea aimed at reducing regional inequality. (Look at any of the key social metrics—transport, for example, where Northern Powerhouse Rail is constantly in limbo, trains in the North are “ruining people’s lives,” and spending per capita in London is still over double that of some UK regions—and judge for yourself whether that plan is working.) But, in more evidence that shows UK politics increasingly resembling the United States, “leveling up” in practice bears a resemblance to congressional “pork-barrel politics,” where bills are supplemented with “bacon” for supporters’ constituencies. It’s unsurprising, for example, that then-housing secretary Robert Jenrick’s 2020 Towns Fund disproportionately channeled public money into regions where Conservative members of parliament were barely holding on to their seats.

Johnson is gone, but “leveling up” stayed; a relative of former chancellor George Osborne’s “Northern Powerhouse” slogan, but with implications for the whole country—and rewards for those willing to support it. For a brief moment, fans of both regional investment and food-based political metaphors were in dreamland when Johnson successor Liz Truss announced the need to “grow the economic pie.” Notwithstanding the fact you can’t grow a pie, Truss and chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s chaotic libertarian mini-budget quickly crushed those dreams, sending the UK markets into freefall. New Prime Minister Rishi Sunak inherits the nation’s shrunken, crumbling pie, desperately searching for easy bits to scrape off. And the arts—international and outward-looking, promoting critical thinking and structural questioning—are hardly the current government’s flavor of the month.

Onlookers living abroad might be forgiven for thinking that 12 years of Conservative rule would have brought about some consistency that arts organizations could at least work with, in lieu of genuine support. But, since 2010, 13 ministers have held the post of Secretary of State for the Department of Culture, Media and Sport. (For comparison, Tony Blair’s Labour administration appointed just two ministers, over a ten-year period from 1997 to 2007). Regardless of their various merits, that amount of chopping and changing is hardly helpful in securing the long-term support that helps produce great art.

That England’s national opera company has been instructed to move somewhere vaguely northern sometime soon is a move straight from the chaotic playbook of recent iterations of the DCMS. Were any of the relevant authorities in Manchester consulted? No, confirmed outgoing ENO CEO Stuart Murphy on last Friday’s edition of BBC Radio 4’s Front Row. A spokesperson for Opera North, the Leeds-based company who tour the Manchester area, and who were originally formed under the name English National Opera North the last time somebody suggested this kind of split, told VAN: “We feel that it is premature to discuss the situation further since there has as yet been no consultation on this, or any other aspect of the funding decisions announced last Friday.” It seems nobody informed them either. (In a statement, an Arts Council England spokesperson said: “English National Opera’s future is in their hands—at this early stage we have announced our funding plans for the next three years, and now we hope to engage in detailed planning with them,” all but confirming ACE’s new guiding philosophy: Fuck around and find out.)

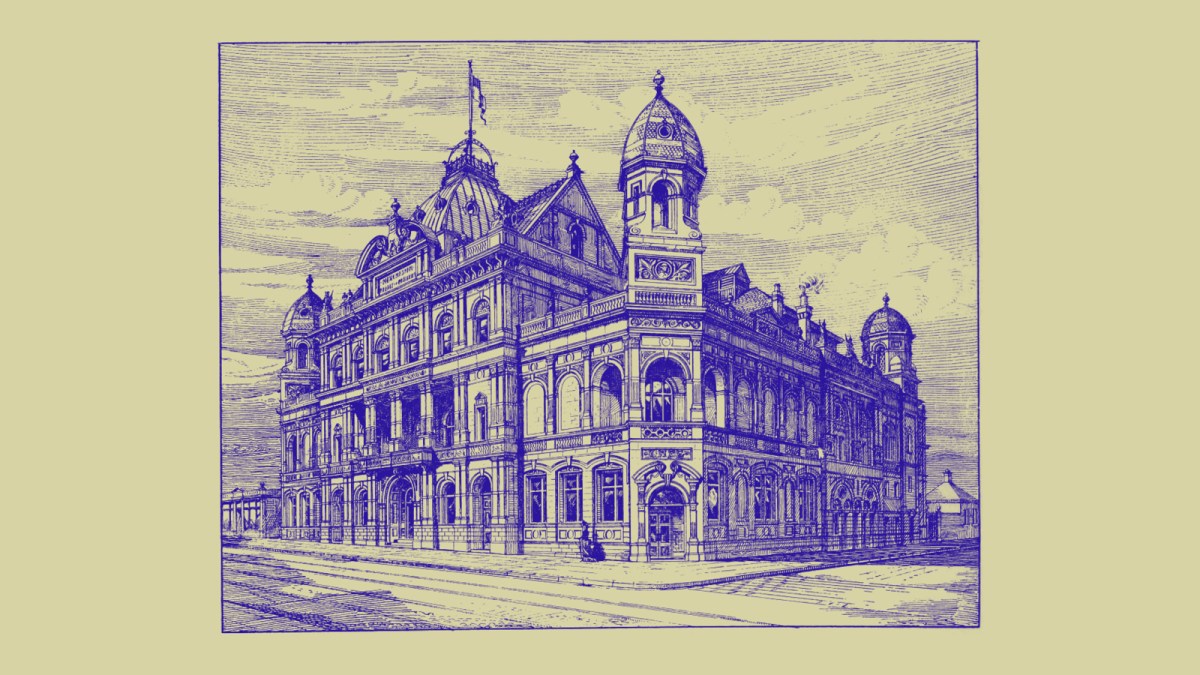

As a resident of Manchester for the past six years, a Northerner all my life, and one of the UK’s few classical music journalists not currently based in London or the South East, my heart goes out to both ENO and to whoever gets lumped with this project in Manchester. If ENO does move to the North West, it will be rushed, begrudging, and painful, given how many jobs will be found to be untenable in the process, and how many livelihoods will be impacted as a result. If Manchester is chosen as ENO’s new home, the city will somehow have to find a suitable venue, an audience in a city that historically isn’t overly keen on opera, and the money to pay for it, either from a cash-strapped city council who have already plunged significant funds into the much-delayed Factory International building, or from foreign investors with deep pockets and their own motivations away from ENO’s egalitarian founding principles. The annoyingly ubiquitous Tony Wilson misquote, “This is Manchester, we do things differently here,” (a statement increasingly detached from the fast-changing Manchester landscape) also rings true. Where’s the £17m for a new, Manchester-based opera company, rather than palming one that’s deemed to be failing off on the city, with huge disruption to all involved?

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Several musical organizations were hit heavily by Friday’s announcements, revealing which organizations had qualified for NPO funding, and to what extent. The 100 percent grant reduction of the Britten Sinfonia, a fine chamber ensemble out of Cambridge, has largely gone under the radar. Welsh National Opera (WNO), Sound and Music, and the Glyndebourne Tour are all organizations with successful track records, and yet all face future-changing reductions of funds.

But the final thought is with the UK’s contemporary music ensembles. Through the last remaining vehicles of establishment outrage, reinvigorated appeals to celebrity (leaned on by the ENO top brass in recent times), and the fact that ENO does ultimately command a sizable audience, I have no doubt some version of the company will survive. How big it might be, where it might be based, and who foots the bill are three huge questions that should have been answered before, and desperately need to be answered next. The fact that the critic Richard Morrison, writing in The Times, even suggested the idea of the company pivoting to an American-style, completely commercial operation—plucking a £12m-a-year sponsor out of thin air at the same time—shows the level of influence the company still holds. As I speak, Bryn Terfel is rallying the troops via Change.org. All power to their collective elbow.

But aside from ACE’s other clearly contradictory decisions—why take money from touring groups like WNO, or the Glyndebourne Tour, active agents in “leveling up”?—there are other, quieter, more worrying concerns about for whom Arts Council funding should be. While many socially-worthy organizations have received life-changing grants, less consideration has been given to artistic projects that simply wouldn’t survive in the commercial sector. I think of Psappha, which almost exclusively performs challenging pieces of art music from the 20th and 21st centuries. Like ENO, they too lost 100 percent of their grant, but without a consolation budget. (There’s no need for Psappha to relocate, because… they’ve been in Manchester for 30 years.) Psappha has supported hundreds of emerging composers, and regularly hit their niche, putting on things nobody else in the city would touch. “Keep going,” a supporter tweeted below a recent Psappha announcement. “How?” one of the players replied.

Spare a thought too, for those contemporary music organizations applying for money who missed out on funding entirely. Riot Ensemble has never received NPO funding, forced every year to apply for the annual merry-go-round of National Lottery funding and other pots of money. They missed out again this year. “We’re not naïve, we know we’re a small part of this,” artistic director Aaron Holloway-Nahum told VAN. “But the thing about this adventurous new music is that it is such incredibly good value for the investment. Even if you completely defunded all the organizations we’re talking about here (Psappha, [London] Sinfonietta, Sound and Music, Riot Ensemble), it saves less than about £1m, or 0.2 percent of the portfolio per year. So for less than one-half-of-one-percent of this funding, they could literally found and sustain one of the greatest, most eclectic new music communities in the world. Honestly, at that level of funding it would be a global leader in its area, and it would have been rocket fuel for us.”

In its wide remit, Arts Council England should support art that would otherwise be impossible, at arm’s length from government interference. It’s doing neither of those things. It’s time for a serious rethink. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.