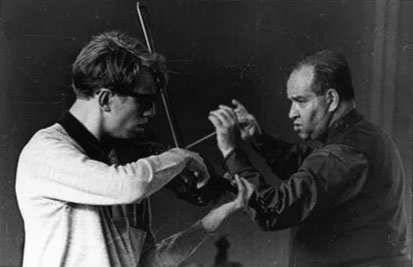

Violinist Gidon Kremer was unusually quick to develop an aesthetic of his own and has long been ahead of his time. This independence is most obvious in his love for contemporary music, which he developed as a conservatory student in Moscow and which brought him into contact with composers such as Pärt, Schnittke, Gubaidulina, and later on, Weinberg. But Kremer also has a history of fascination with repertoire at the edges of the canon, such as Schumann’s neglected Violin Concerto, and with bringing musical worlds together. On his second recording of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto (1980), Kremer chose Alfred Schnittke’s cadenza—unheard then and still rarely played. It’s not difficult to imagine how executives at his label at the time, Philips, must have reacted. Kremer was an early and perceptive critic of the Western classical music industry, with its conservatism and fixation on stardom—criticisms Kremer began making as early as the 1970s, when complaining about the business was not yet considered de rigeur.

In 1981, Kremer founded one of the first chamber music festivals in the German-speaking world in Lockenhaus, Austria, realizing his dream of a home for collaborative, spontaneous music-making. 16 years later, he founded the Kremerata Baltica. Kremer also found a characteristic tone early on in his violin career: direct, raw, full of tension and gripping intensity. “You hear the first bars and you know it’s him,” said violinist Veronika Eberle of Kremer’s recording of the Mozart violin concertos with Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1984). “His playing has an incredible number of ideas in a small space; it’s a unique, slightly crazy Mozart.”

As a political observer, Kremer recognized Putin’s imperial aspirations early on. In an interview in January 2014, before the annexation of Crimea, Kremer said, “Part of the Russian soul is also its delusions of grandeur, and that is not harmless. Putin is smarter than people think. That is the problem; that is the danger. He’s playing with the credulity of the Western world.”

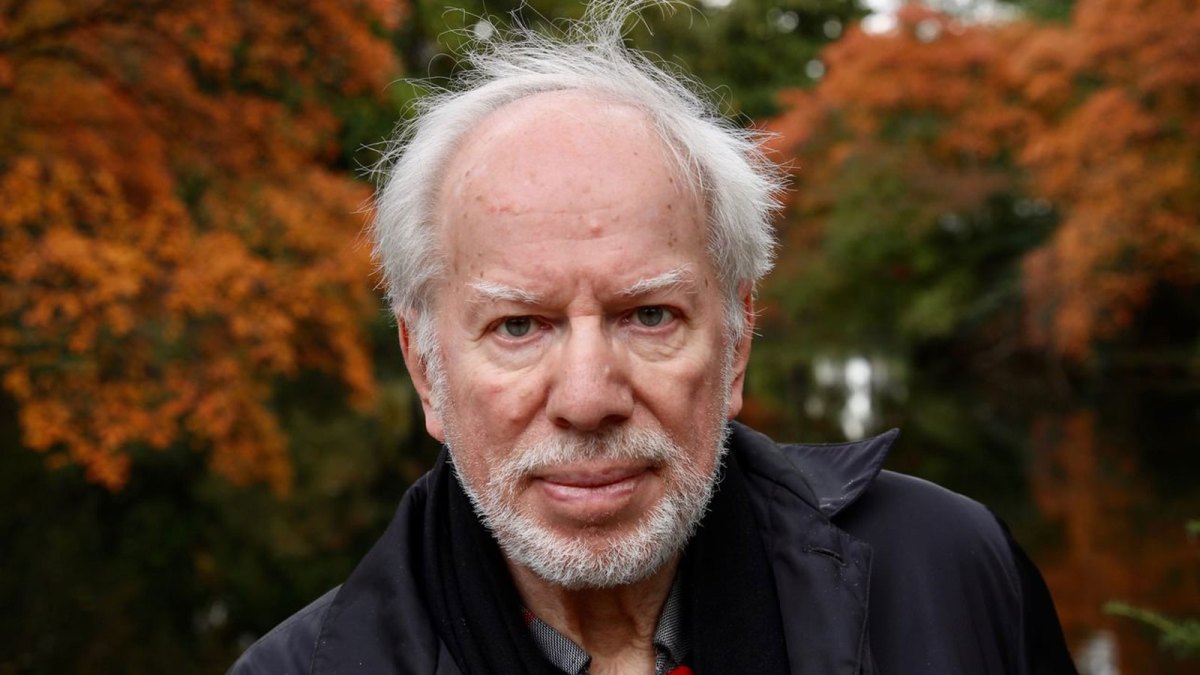

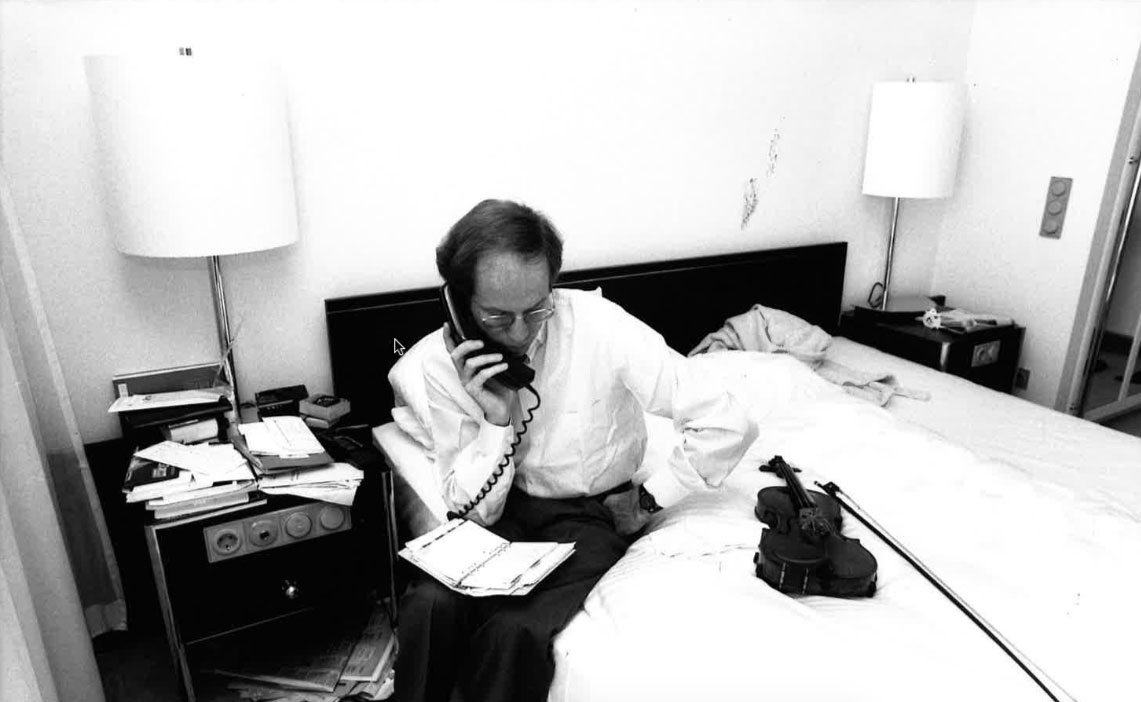

I met the 76-year-old on a Friday afternoon in his apartment in the well-to-do West Berlin neighborhood of Charlottenburg. The space was airy, with an open-plan kitchen, but there was hardly any furniture: Instead there were boxes of books on the floor, concert posters on the walls, and a few pictures from a bygone era. “I’m rarely here. It’s a place to stay, but I still need to design it,” he told me. “I’m trying to think of Berlin as my home now, but I don’t quite feel it yet.”

VAN: In an interview you gave in March 2022, shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, you said, “At the moment, I’m so desperate that I’ve even started wondering: ‘Is there any meaning in making music?’” Have you been able to find the meaning since?

Gidon Kremer: At the beginning of the war, I had this desperation, and an awareness that you can’t save the world with beauty came along with it. The feeling that evil is stronger, and that you can’t fight it with music, was very present. It’s not that I’ve reconciled myself to the war in the meantime, on the contrary—I’m just as disturbed as I was then. Still, I try to believe that what we do has meaning. I don’t really have a choice. Music can be healing, but the “music of war” cannot be.

Two weeks before the war began, you were in Moscow with your Snow Symphony project. What was the atmosphere like?

There was a certain tension in the air. Many of my friends were worried, but almost no one thought the war would actually break out, myself included. The paradox is that if I believe the stories, people still don’t feel the war in Moscow. Some try to talk their way out of it by saying that it’s complicated. But I’m trying not to be in touch with friends and acquaintances who take this position. For me, it’s not complicated. You can’t just invade a neighboring country.

My good friend, Georgian composer Giya Kancheli, always says, “It’s all Putin’s fault.” He’s not wrong, but I wouldn’t simplify it that way either. For reasons that historians can explain better than I can, many people are behind the government: they support the idea of being an empire and more important than other countries. You see this macho principle everywhere, but it’s completely foreign to me.

Since the invasion, there has been a lot of discussion about what music should or shouldn’t be played, where it should be performed, by whom… Where do you stand on these questions?

I probably wouldn’t put together an all-Russian program right now, because I want to avoid implying a political message. But I’m not going to write off Russian culture as a whole because of everything that’s happening, like the countries that are trying to ban Russian music. On the one hand, it’s strange. But emotionally, I understand it, just as I understand that Wagner is not popular with a large part of the population in Israel. But I’m really more concerned with the question of how artists today confront evil. Whether they side with it, whether they remain silent…

How do you define remaining silent?

I realize that people in Russia are living in fear. The plague is everywhere. Instead of loudly exclaiming their support for the political fiat of the hour, certain decent people may decide to fall silent. I understand that. But I admire those who maintain their beliefs and take a stand against the official propaganda, whether privately or publicly. Of course, that’s much easier abroad. And then, as you know, there are some artists who explicitly identify with Russian imperialism and its leader, which is very sad to see.

You used to perform with Valery Gergiev, but haven’t done so for over a decade. When did you become aware of his political views?

I don’t want to insult the artists who are along for the ride. I just question them, and I think it would be honest for them to question themselves. But they’re probably hoping to benefit, or are benefiting already, from attaching themselves to politics.

I happened to come across a book yesterday while I was unpacking. I didn’t even know it was in my library. [He puts a coffee table book on the table.] It was published in Russia in 2007, and has a wonderful title: Admission to Paradise. It’s about competing propaganda on the Eastern Front; you see how similar both armies’ propaganda is. Today, a book like this would definitely not be published in Russia.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Can you imagine performing in Russia right now?

Absolutely not. And I don’t think that will be possible again in my lifetime. I doubt that I’ll ever be able to set foot on Russian soil again. I’m not Russian, but I still have good friends there and value the language that Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Bunin, Pasternak, and Brodsky spoke.

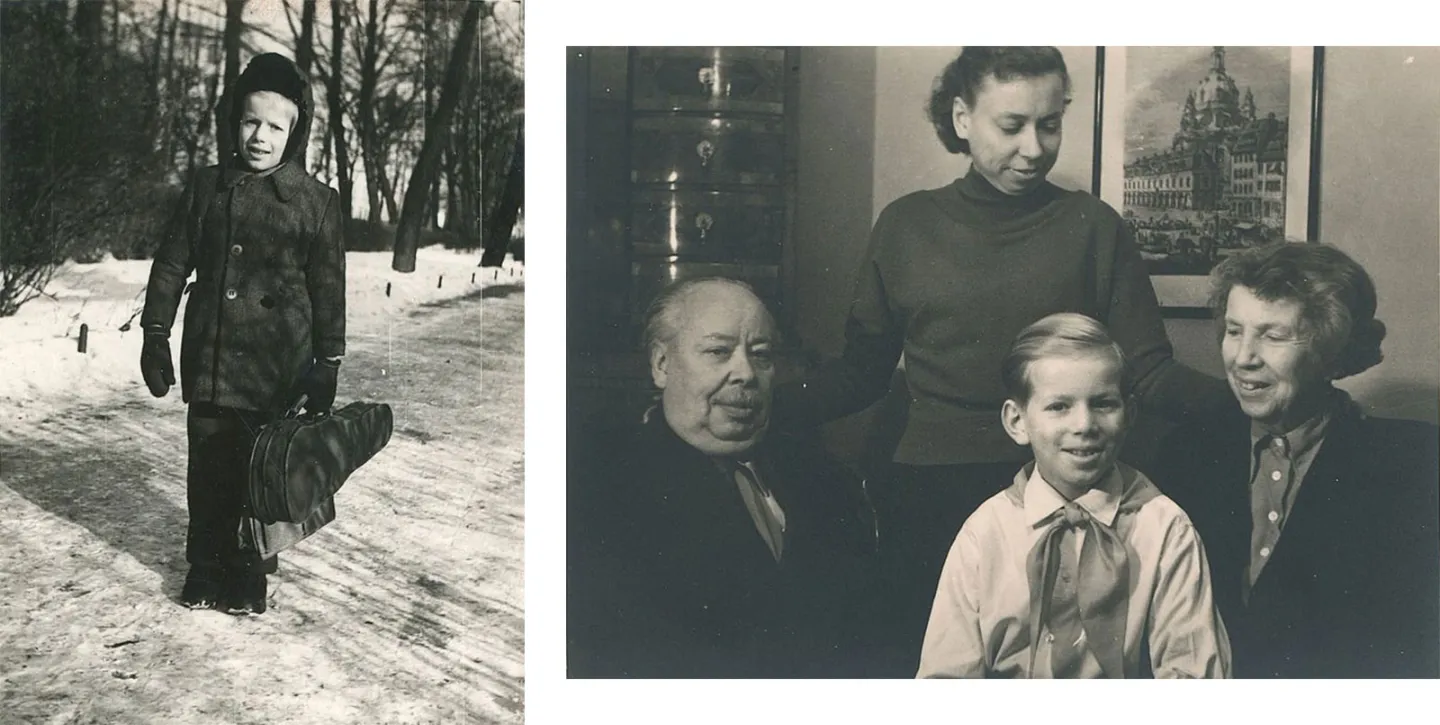

35 members of your father’s family were murdered in the Holocaust, including his first wife and young daughter. You once said, “I was the survivor’s son. In order to survive I had to be better than the others.” How did you react to your father’s family history as a child?

As a child, I tried to convince my father to move on from his trauma: “It’s over now. Rejoice in the present.” That was totally naïve, of course, because you can’t just forget a trauma like that. It wasn’t until later that I understood how it remained within him.

I also remember clearly how upset my family was during the invasion of Hungary in 1956. My grandparents sat by the radio, shocked. They were always refugees, always trying to escape from the country they were in, sometimes succeeding, sometimes failing, as with the Soviet Union. It’s a dramatic family history, and I felt every story, of course.

How did you deal with that?

I wrote a lot and started keeping a diary early on. Looking back, and from a psychological perspective, you might say it was a kind of autotherapy. Actually, talking to you now, I’m realizing I may have been imitating my grandfather, who used to write a lot about music when I was a child. Unfortunately, I don’t know what exactly he wrote and where it all disappeared to.

Lots of research shows how trauma is transmitted from one generation to another and what kinds of consequences this can have. In your case, it also seems to have strengthened your resilience, your independence, and your willpower, despite—or because of—the pressure.

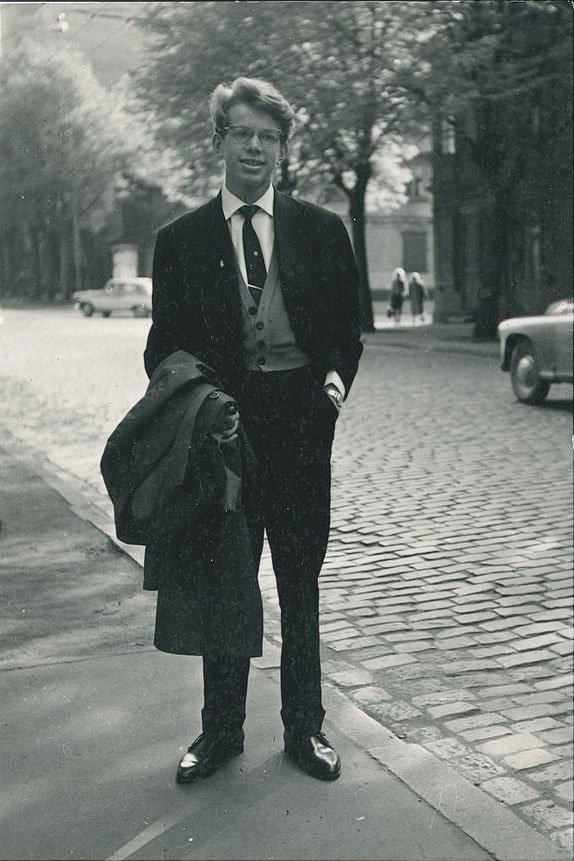

It sounds perverse, but there is often some good in anything bad. The pressure that was put on me—by the system, by my father, by my family’s desire for me to succeed—was important in retrospect, because it taught me the meaning of work. I knew I had an obligation to my family, but I resisted having that be my only thing. I was also glad that I was still given some freedom: my grandmother praised my independence, and even my father used to say, “After you’ve practiced for five hours, you can go play or do whatever you want.” Later, at conservatory, I broke free by exploring the other arts: ballet, film, literature… That helped me immensely. It made me who I am.

What were you reading or watching?

Books by Nabokov; the films of Tarkovsky, Bergman, Antonioni, and Fellini. Somerset Maugham’s memoirs [The Summing Up (1938)—Ed.], which he wrote when he was 64, were good for me as a teenager, they triggered lots of reflection in me. I tried to break free from the violin world—I mean, I was already committed to it anyway—so I went to Jacques Brel and Duke Ellington concerts and spent time with friends who thought outside the official lines. Later, when David Oistrakh [Kremer’s violin teacher in Moscow] tried to get me an exit visa to travel abroad, I was told during a conversation with the Central Committee: “You have the wrong friends.” But they were the right ones.

You mentioned being raised to work from a young age, and you’ve always been impatient and restless. Has that changed as you’ve gotten older?

No, I’m still restless. It’s a blessing and a curse. For me, work always comes first. The violin comes first. Everything else comes after. I wish I’d been taught how to relax as well as how to work. But in the meantime I’ve learned how to not play for longer periods. Because of that, even the pandemic was relaxing for me, in a way. Although: I decided to write every day again. I’d usually get up at 5 or 6 a.m. and sit down to work.

What were you working on?

It’s a monumental project. I’m working on it with an old friend from school, it’s in the form of a dialogue. It’s a sort of witnessing of my existence. If it was a film, it would be a documentary, but a very long one. I’m not really interested in whether anyone wants to read the whole thing; I’m not thinking about how to sell it. I have a need to communicate. I’m not sure where that comes from: maybe from the trauma of my childhood, maybe from my experience trying to escape the restrictions of the Soviet regime, maybe from the curiosity of my ancestors, especially my grandfather.

You started listening to your own recordings during the pandemic as well. Which ones do you think were the most important?

It would be wonderful if I knew, but I really can’t say, because I was fully there in every recording. Or almost every recording: say 92 percent. Besides, there are so many—over 150 CDs. What do you think I should listen to?

I grew up listening to your Beethoven sonatas with Martha Argerich, Gubaidulina’s “Offertorium,” and your most recent recording of the Bach sonatas and partitas on ECM…

Another journalist once told me that my obituary would definitely include the names Schnittke and Piazzolla. Now I’m glad that maybe Bach, Gubaidulina, and Beethoven also have a place in it. I’m not being an obsessive completist about my recordings; I’m also not trying to write my legacy through them. Instead, I’m interested in how I’ve changed, how I felt about something at different times, and the moments when I’ve been particularly lucky with my musical partners. I’ve played with so many conductors, I think close to 500, and with so many extraordinary pianists.

You’ve been playing the violin since you were four years old. Can you imagine what it would be like not playing it?

A few years ago, a reporter asked me if I planned to retire at age 72 or 73, like Jascha Heifetz. I was confused by the question. I live as I live. To quote Nono: “What comes, comes, and what does not come, does not come.” We are all children of God. Who knows what we’ll stumble on?

Old age also has its rules, of course. As my mother used to say: “Getting older is not nice.” I’m pretty relaxed about it, but I do notice insecurities creeping in here and there. I’m slowing down a bit too, though I’m still managing to live the way I want to. But my focus is still on activity, not rest. I wish I had more time—time, but also calm—for my two grown daughters, Lika and Gigi. They never got that from me, and I owe it to them. I admire their energy, I admire their alertness, but I also realize that I’m awkward around my grandchildren. I don’t know the techniques as well as I know them on the violin. I’m trying to find some peace.

You’ve often spoken about not having a true home. Have you found one now in Berlin?

It’s difficult, but at least I’m really trying here. For the last 15 years I’ve lived in Vilnius, but like all the other places I’ve been in for a while—Munich, Paris, New York, Zurich, Basel—I’ve always just been visiting, because I’m constantly rushing around the world.

In a documentary film, you said, “Everything one gives, stays; everything one keeps, dies.” Do you ever think about the question of your legacy, about what you want to leave behind?

I think I’ve played enough notes and written enough words. I would like the Kremerata Baltica, which I started 26 years ago, to continue with or without me. The group is very important to me: it’s a way of passing on my experience and love of music to the next generation, and also they play like no one else. I can say, with a clear conscience, that I’ve lived my life. I wouldn’t wish the hardships I’ve gone through on anyone, but at the same time I’m grateful to destiny. As difficult as they were, these experiences helped me create a fair amount and leave behind a fair amount. But for now I’m still here, and I’m taking pleasure in continuing to form my path. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.