On April 14, the Russian keyboard player Alexei Lubimov and the singer Yana Ivanilova performed a concert at DK Rassvet, a venue in central Moscow which, similar to New York’s (Le) Poisson Rouge, hosts concerts and cultural events and doubles as a club. As Lubimov was performing playing a solo portion of the concert, with two Impromptus from Schubert’s D. 899 set, two uniformed police officers entered the hall, warning the audience that a bomb threat had been reported at the venue.

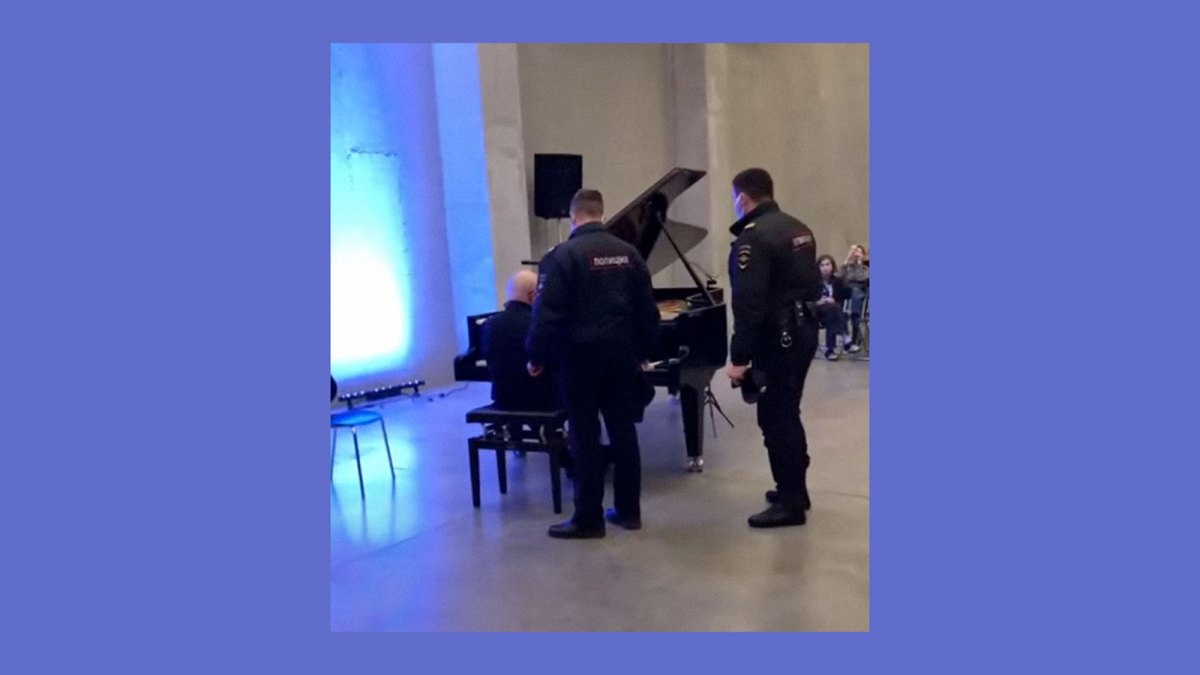

Lubimov kept playing. The policemen stood near the door for a few minutes, then they went to the piano to silence the music. Lubimov finished the thrilling, lurching coda of the second Impromptu—which modulates bracingly from B Major to Eb Major in a handful of bars—while the policemen milled around his instrument, their obvious awkwardness not hidden by their masks. The video quickly went viral. This is Lubimov’s first interview since the concert; we spoke by phone in Lubimov’s expressive mixture of English and German.

VAN: What happened at the performance?

Alexei Lubimov: Two months ago, we announced the program, of Valentyn Silvestrov’s vocal cycle “Steps” with Yana Ivanilova and the Schubert Impromptus and some lieder. It was a planned event, and was publicized normally. There was nothing dangerous about it. But, on the morning of the day of the concert, the director of the hall [Alexei Munipov] got a call—I don’t know from which authorities—and they asked him to cancel the concert. He replied that he couldn’t cancel it because it was sold out, and that there was nothing problematic or dangerous about the program.

Before the concert, [Munipov] asked me and Yana Ivanilova to speak carefully during our introductions to the pieces, without references to politics or the war. And we did so. We just explained who Silvestrov is—a very well-known composer, of course a Ukrainian composer, a famous member of the avant-garde from the 1970s and ’80s—[and talked] about “Steps” and so on.

We performed “Steps” with great success. Then we began the second part, with the Schubert Impromptus, which were supposed to be followed by Schubert songs. But during the end of the first Impromptu, the policeman came into the hall, and announced loudly, “You have to leave the hall, because we have to check for a bomb. There’s been a bomb threat.”

I immediately understood that this was a provocation and that it was fake. So I continued to play, going into the second Impromptu. And the police were waiting at the entrance of the hall. But after four minutes, they came up to me at the piano. I was worried that they would close the piano, but they didn’t. When I finished, there was great applause, and cries of “Bravo!” and so on.

They said we had to stop. I asked why. They explained again that there was probably a bomb, and that they were waiting for the bomb-sniffing dogs to arrive. I asked how long it would take. They said 15 minutes. So I told the audience, “Please, let’s follow the procedure. We’ll stop for 15 minutes.” Everybody understood immediately: There were no protests, no political statements. It was absolutely quiet and polite.

We left the hall, but we couldn’t go back inside. The bomb-sniffing dogs didn’t come until two hours later. The police said they were just following orders, and they obviously didn’t know the music or why they had these orders. But it was immediately obvious to us that they wanted to stop the concert because Silvestrov had spoken clearly about the war and Putin’s dictatorship in interviews. [Silvestrov is currently in Berlin.—Ed.] The authorities probably recognized the name: “Silvestrov means you’re against Putin and against the war.” They probably thought his name was a dangerous anti-war symbol.

[The concert was interrupted] although Silvestrov’s pieces have been performed in this hall—just counting this hall—four times since December. He’s a famous composer, and despite his Ukrainian heritage his works are played often in [Russian] concerts of contemporary music. Even in these dangerous times.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Did you look at the concert as a protest against the war? Or were you just playing music by Silvestrov?

Of course we couldn’t call our concert an anti-war concert. But it was obvious to the people in the hall: Since we’re playing Ukrainian music, we’re against the war. The audience was made up of the so-called Moscow intelligentsia, musicians, writers, poets, friends, and acquaintances…

What was going through your head as you played the last bars of the Schubert Impromptu with the policemen standing next to you? Were you nervous?

No. It was strange: The policeman seemed helpless to me. And I wanted to play to the end. It was like an absurdist play.

I wasn’t scared and I didn’t doubt that [the bomb threat] was fake. I thought I might be interrogated, but I wasn’t. I think the policemen were just doing their job. They didn’t know what the reason behind it was. Anyway, they were late, because we’d already played Silvestrov’s music. So Schubert ended up sacrificing himself for Silvestrov and Ukraine. [Laughs.]

Us artists had to leave the hall along with the audience; there were probably about 50 people on the street outside the hall. There was some applause and some calls of “bravo,” and someone said, “What a pity, that was probably the last time we’ll hear Silvestrov.” I answered, right away and loudly, “No, not a chance. We’ll keep playing Silvestrov.”

We waited at least another half an hour [for the bomb-sniffing dogs]. Nothing happened, so we went to the café across the street. Members of the audience and our friends were there, we ate, drank, and exchanged opinions and information. The police waited until midnight for the dogs, and they really did come. But they didn’t find anything. [Laughs.]

Were you afraid that you’d be interrogated the next day?

As soon as the next day came, I wasn’t afraid anymore. I had a feeling—not fear—that I’d probably have to talk to the authorities at the border, because I left for St. Petersburg on Sunday, then took the bus to Helsinki on Monday before flying from there to Paris. But nothing happened. It was probably too local to Moscow, a spontaneous reaction to the name Silvestrov. More could have happened after the international media covered what happened. But there was no reaction, thank God.

Have you talked to Silvestrov since the concert?

I’m going to speak with him today. I’ve known him since 1968: We’re friends, and I’ve been playing his music since then. As an avant-garde composer he wasn’t exactly welcome in the 1960s and ’70s either, there was a campaign against avant-garde art in Russia at that time.

When are you planning to go back to Russia again?

Probably in late May.

In March, the harpsichordist Elizaveta Miller decided to emigrate from Russia with her family, she was your colleague at the Moscow Conservatory. Have you thought about leaving too?

No. I guess I had the opportunity to do that earlier on. I do have dual citizenship. But although I really do hate the current Russian government, this dictatorship, this censorship, and all it is doing against culture, freedom, and free thinking…I’m still Russian. I never want to lose Russia as a country. I will never be against Russia, but only against the people who have put Russia in this state. As long as my profession and my life are not under threat, I’ll always come back to Russia. I’m not the kind of person who can only go one way. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.