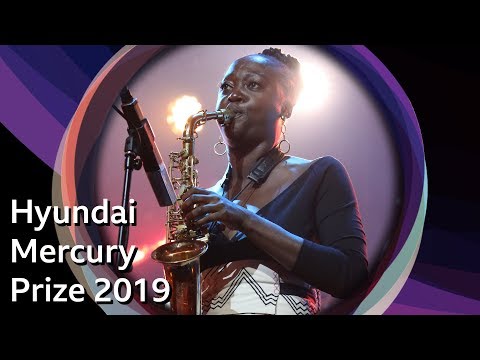

Cassie Kinoshi’s compositions appear on her SoundCloud in a couple of unassuming annual collections. The six-minute clips are given generic titles like “Compositions: Instrumental Showreel 2020.” But beneath their utilitarian form lie collections of substantial creativity. “Afronaut,” a gritty Afrofuturist track from the Mercury Award-nominated SEED Ensemble, sits alongside “If She Could Dance Naked Under Palm Trees,” her Nina Simone-inspired piece for the London Symphony Orchestra. Scores for the BalletBoyz meet brass ensemble pieces written while studying at London’s Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. As well as her ongoing work as a composer, Kinoshi is a fixture in the much-lauded London jazz scene. If you missed Cassie on sax in SEED, you can find her KOKOROKO, an Afrobeat collective run by trumpeter Sheila Maurice-Grey. There’s also Nérija, a female-fronted sextet featuring, among others, tenor saxophonist Nubya Garcia (whose recent release Kinoshi also appears on).

Yet Kinoshi’s sound isn’t as eclectic as her busy schedule might suggest. Balancing solid performing commitments with a burgeoning composition career (including recent commissions from the Aurora Orchestra and the London Sinfonietta), she presents her work in a way that is less showreel, more mixtape. They’re concentrated collections, focused and stylish; her music is sure of itself.I spoke with Kinoshi recently about how these different facets of her work inform one another (and where collaboration fits into the picture), where Fela Kuti meets Sergei Prokofiev in her playlist, and her beef with Pierre Boulez.

VAN: How do you choose to identify, artistically? Composer, artist, musician?

Cassie Kinoshi: I think putting yourself in boxes is never a good thing. I guess I’d say composer and musician, but I wouldn’t say more one or the other, because they both bleed into each other—especially being involved in improvised music.

One of the reasons I’m particularly drawn to your sound world is because of the really strong arrangements. Where does arranging fit into that picture? And who are your inspirations from that world? I can hear a bit of Maria Schneider in there…

Maria Schneider is definitely a huge influence in my approach to writing for big bands and large ensembles. I really admire her as a composer and arranger—and as a person. But I don’t know, everything kind of bleeds into each other, as I said. I love to take. I like to apply, say, what Fela Kuti does [with his arrangements] to what I do. I was really obsessed (and still am obsessed) with Prokofiev, and it all melds into one in how I approach writing.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Did your interest in Fela come through your shared connection with Trinity Laban?

I delved more into him at Trinity, but my parents listened to everything. My dad is half-Nigerian so I already had that sound world there. But when I got to university, and found out that he went to Trinity, I tried to [actively] celebrate him more through my projects.

And where does the Prokofiev obsession come from? “Peter and the Wolf”?

No! I was obsessed with the “Cinderella” suite. When I went to study composition, I got introduced to more Russian composers, and so I found his score for the “Cinderella” suite in the library. Literally, I went to the BBC Proms in my first year and sat right at the top [tier of Royal Albert Hall] following the orchestral score. That’s how nerdy I got with his stuff.

Sometimes arranging gets dismissed as one of those “practical musicianship” things, and it becomes sort of detached from composing. How integral is the idea of arranging when you’re writing?

Super important. It’s just like learning an instrument: Transcribing, listening to, and imitating players is really important in understanding the instrument and developing your own voice. I think the same is [true] with composition.

It’s a way into learning the different voices of some of the great composers and then applying that to your own work. And it’s given me some of the skills that I have: understanding the colors of the palette and the paints that are there. For me, it’s a skill that I’ll continue to work on forever really, because there’s always something new to learn.

One of the things that distinguishes you as an artist is your clear idea of your role within each ensemble that you work with, which informs how you interact accordingly. For you, what’s the difference between a band and a collective, and where do you fit into that as a composer?

I don’t want to use the word “interchangeable”—I don’t really like that word—but I think a collective is where musicians can be more fluid. The music pretty much stays the same, but you can have different members flowing out or coming in. It’s more of a collective when things are open to change.

I think a band is when there’s a little more of a settled lineup and, at least in my experience, more of a family feel. Even if it’s one person leading and making decisions. In Nérija, we all make decisions. But in SEED Ensemble, most of the decisions come from me. But I would say they’re both bands.

It’s interesting to hear that, because from my perspective a collective is a situation where artistic decisions are open to the floor; where there’s no set leader?

I agree with that definition as well! I think the distinction comes because the media tends to mix things up. What I think is still very much happening is that the word “collective” is thrown around [inaccurately]. Sometimes the word “collective” is used to describe Nérija and SEED Ensemble.

Firstly, the lineup doesn’t change. Secondly, SEED is my creation. Maybe it’s a little bit coming from ego, but I want people to know that this band is led by me. I think when you say “collective,” it kind of discredits the work that people have done.

When you’re writing for SEED and working on interdisciplinary projects, how much collaboration does take place?

The writing process is extremely collaborative. In KOKOROKO and Nérija, everyone is the composer and we write together. For SEED Ensemble, I will usually bring finished or half-finished compositions to the band. It’s still a form of collaboration, but not as intensely as the other two bands. Everyone performs the music with their own voice and interprets it with their influences. That’s still a form of collaborative writing in my opinion—especially with media that has improvised solos, because they are writing on the spot in the sound world that I’ve created for them.

In terms of interdisciplinary work, I’ve been quite lucky to be involved in things where, as a composer, I still actually get quite a lot of artistic… what’s the word?

Say?

Yeah, something where my voice is still heard in those spaces. So the theater I’ve worked on has been able to have discussions with the director and the sound designer and what I say is taken on board while still being able to achieve the vision of the writer and director.

In the discourse around creativity in the UK, there’s a lot of emphasis on collaboration at the moment. Do you feel a lot of that happening in the creative industry?

I think quite a lot of how it’s presented in the media is quite a shallow perspective: It doesn’t delve deeply into what’s actually there. There’s so much going on that I’ve had to kind of discover myself because it’s not presented as openly as what’s going on in London. I don’t think that you can improve as a composer or musician if you’re not looking outside of the scene, if you’re just looking at what’s mirrored back to you. There’s no way for you to grow beyond that.

Can you look at the way other music histories are written, around places, narratives and people, and see a similarity in the narratives of UK jazz?

Yeah, I guess in a sense. Which is a shame. There’s always going to be the names that we know, but people in the media have a responsibility to dig up everything else.

Have you had to dig to find representation in other aspects of your music making? What’s representation like in the theater and film circles you work in, for example?

In terms of film and theater, there needs to be a lot more work in terms of representation, especially for Black people. I don’t really know many Black composers for theater or film. I’m always looking for people to look up to and connect with. And although there are names in classical music, like Errollyn Wallen and Shirley Thompson, you kind of have to dig for them too, unfortunately.

And there are young Black composers like Hannah Kendall, but you have to search [even harder] for them, and they’re not always given the same opportunities. So film, theater and classical really [need to] work on that, and not just when prompted by Black Lives Matter. We need it at least to be a consistent thing that keeps happening, not just when a tragedy happens to the Black community or other ethnic minority communities.

It all starts with education. I think people don’t realize how much it influences you to see yourself in education, and music education especially. If you see a composer and think, Oh, he looks like me, or He’s from the same kind of background as me, you’re going to connect to that more. Maybe that pushes more people into then writing music, which then leads to more Black composers, and then…

I follow you on Twitter, and really admire how open you are about all aspects of your career. I’ve got to ask you though, what’s your beef with Boulez?

You know what, I just don’t enjoy it. I can really appreciate that he’s amazing with notation, and that he knows what he’s doing with the tools of the orchestra… But every time I see it live or try and sit and really listen to it, I just can’t connect with it. It just leaves me feeling really anxious.

I remember listening to one of the Boulez Piano Sonatas in a concert at my university and it was just…

Did you enjoy it?

I don’t think enjoyment came into it. It was more of an experience.

If you can appreciate the skill it takes to play it and write it, then fair enough. But…

I wanted to ask you about the concept of “less is more,” after recently speaking with your colleague [saxophonist] Shabaka Hutchings. He said, “Less is not more; more is more, less is less.” Lots of things happen in your music; it’s quite dense texturally, and there are lots of lines of counterpoint, especially in your arrangements. What are your thoughts on “less is more”?

There are ways to write where there are loads of things going on and it works. But you need to know how to make it work, to have the skillset to make sure it works, and to study the people that use loads of things. Like Boulez, for example: Boulez works because he knows what he’s doing.

I think maybe when you’re learning, “less is more” means having a core idea that everything grows from. You can be as complex as you want, but good complexity still leads back to that fundamental idea. I think that means, don’t just stuff everything into something, because it’s not always going to work. You have to make it work yourself. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.