New Year’s and third lockdown resolution: trying to listen to and rank every Schubert song. (I’m not done yet, but I attempted something similar for the Scarlatti sonatas.) Because my impressions are very subjective—not to say flat-out wrong—I also decided to get a more holistic view of this oeuvre, which numbers somewhere around 700 lieder, depending on whether you count certain part songs and fragments.

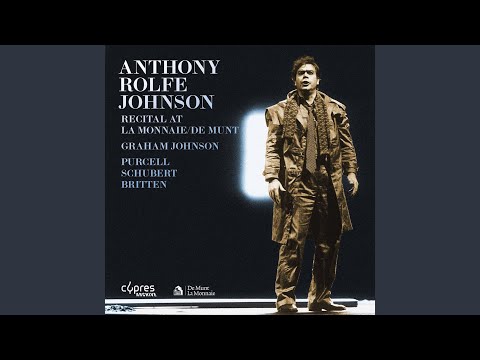

There’s probably no one who knows these pieces better than Graham Johnson. Born in 1950 in the British colony of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), he moved to London as a teenager where he studied piano at the Royal Academy of Music. At 35, he embarked on a survey of every Schubert song ever composed, organizing the project and accompanying a Who’s Who of lieder singers. The first disc was released in 1987; the last, in 2005. In 2014, Johnson brought out a companion volume of history, translation, and analysis. He’s not done with Schubert yet.

In December, we spoke on the phone, the amateur completist asking the questions of the pro.

VAN: Since finishing your edition of the complete Schubert lieder, have you actually gone back and listened to your recording of every song?

Graham Johnson: No, I haven’t. That’s because every recording is a photograph of where one is with a song at a given time. There’s absolutely nothing definitive about anything in a performance. I have continued a lifelong engagement with Schubert’s songs, of which the recording of the lieder was a phase—the phase that happened to be preserved.

I wish now that I could do it all over again. I’ve had many new ideas. The process of learning about the songs has been unending. I suppose it’s a bit like the producer who does a “King Lear” when he’s 25 and again when he’s 50. He doesn’t necessarily think that the “King Lear” he produced at 25 is the definitive one.

If you were to start recording again, what are some specific things that you would want to do differently?

Bearing in mind that in each case I would have to tailor the situation to whichever singer happened to be available: I would try and do more of the original keys. But that’s always a losing battle in lieder, because while the majority of Schubert songs are written in the higher key, the majority of male singers are baritones. If the lieder were never transposed, [Dietrich] Fischer-Dieskau could not have recorded his complete Schubert songs.

On my side of things, it would be what I’ve learned about how Schubert [uses] evidence in the scores. That has become much more acute over the years. You get to know the composer’s hieroglyphics. You get to know how he notates tempo. The difference between alla breve and two in a bar, four in a bar; the difference between geschwind and schnell, and mässig langsam and ziemlich langsam; all these very particular tempo markings that Schubert wrote.

Actually, the differences would be similar to those of a conductor who has done a very exuberant Brahms symphony, and as he gets older decides now to give it a more spacious reading, a more philosophical reading—not so much to do with enthusiasm and youthful brio, something more reflective.

Certainly when I recorded the first volume in the series, with Dame Janet Baker, it was not me who suggested tempi. [Laughs.]

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

In interviews, you’ve mentioned certain experiences that young people need to go through before they start understanding Schubert. Did you have specific experiences in mind? Being in unrequited love seems like an obvious one.

Everything that we are and experience adds up to the subtlety and the depth with which we perform. However, there is a fallacy about being able to better cope with certain texts about unrequited love because one has been in unrequited love. When you’ve got a part in a play as an actor, it’s your entire skill to depict whatever is required of you. On the whole, if you’ve been through the mill and you’ve actually known some pain, in the final analysis it may affect how deep you are as a person. But I don’t honestly think that a person who’s a gifted singer is going to sing something significantly better because they’ve had a mirroring or equivalent circumstance in their life.

It’s going to depend on how good a singer you are; how you manage the passaggio and mezzo voce; how good your German diction is; and a whole slew of skills and abilities other than your claim to have suffered unrequited love, other than a fellow feeling of emotion with the actual protagonist of the cycle.

The musicological debate about Schubert’s sexuality hasn’t been settled. It seems like the complete Lieder would be a rich body of work from which to take clues or suggestions that could inform that debate.

When Maynard Solomon proposed that Schubert might have been gay in his article “Franz Schubert and the Peacocks of Benvenuto Cellini,” it produced enormous scorn and fury, particularly from the late Rita Steblin, who worked, in her own words, to clear Schubert to the “calumny” of homosexuality.

Solomon said out loud what quite a lot of people had been saying for many years. For example, in the 1970s, I spoke to Walter Legge, who was [Elisabeth] Schwarzkopf’s husband, and was in Vienna in the 1930s researching the life of Hugo Wolf. He had managed to speak to some of Wolf’s friends who were still alive. He told me, for years and years, that there was an understanding that Schubert had been homosexual. It’s the type of thing that was never, ever officially spoken about, and denied if it ever came to being written down on paper, but there was such a thing as word on the street among people who’d heard it from [other] people in the 1880s or 1890s.

I’ve noticed there’s a character to Schubert: People love this composer in such a particular way. Although they wouldn’t aspire to be like Beethoven or Mozart, because those two icons are way above them, they somehow feel comfortable if Schubert is more or less in their image: a man who likes a bit to drink, is a bit overweight, maybe likes to go down to the pub. And it goes beyond sexuality, because there are those who want Schubert to be rigorously anti-clerical in terms of his attitude to the Catholic Church, and there are those believers who want Schubert to be extremely religious.

I think it’s fair to say that it’s very possible [Schubert was gay], but by no means completely provable. Because when you talk about a person’s sexuality, you actually imply who they’ve been to bed with; at least that’s what people mean. And we are not absolutely certain of anything to do with Schubert’s sexual life apart from the fact that he contracted a venereal disease.

One of the biggest pieces of evidence in favor of the homosexual idea is the lack of evidence of anything in the opposite direction—in terms of love letters to women. The most passionate words of attachment that he ever wrote to any human being were to the good-looking, charming and very charismatic Franz von Schober. I would say there’s no other letter extant that reaches the heights of affection and passion that we get when Schubert writes to Schober.

Do you think it matters if Schubert was gay or not?

I don’t suppose it does, except if you are very fond of a person and interested in him or her—where would the art of artistic biography be if we’re not curious in following up the lives of the people?

But I think Schubert’s greatness, and his Olympian sense of creative detachment, goes beyond him being engineered and fueled and driven by sexuality alone. I think this is true with any great artist, unless you’re a person who makes a living in writing romantic novels or pornography or on-your-sleeve work, with your sexuality as your main raison d’être. If you’ve got bigger fish to fry, if you’ve actually got bigger issues to think of—the shapes of symphonies and sonatas and song cycles—it doesn’t matter.

I don’t care either way because whatever the truth of the matter, it would not make me love and revere Schubert one iota less. [But] I think there is a curiosity about the people that we revere. Why do we bother tracking down the identity of Beethoven’s immortal beloved?

[Schubert’s] Vienna was a police state with Metternich’s police regularly reading people’s private correspondence, which would lack certain details since people were very careful about what they put in the mail. People went to an awful lot of trouble to hide from the authorities that they were ordinary, sexual, transgressing beings, because they didn’t want to be found out and because they didn’t want their private business to be a subject of police control, blackmail, or observation. When we read some of the Schubert documents of the time, it’s like everybody’s in a golden bubble of not being sexual or bigamous or adulterous or homosexual or anything like that. You read the documents and it’s a sort of cheery world where everybody is spared the sin of sexuality.

Economically, things have changed a lot since your recording of the complete Schubert songs. Do you think it would be possible to find a label to do such a recording of the complete Schubert songs in 2021?

It’s very difficult to say, because everybody doesn’t want complete [sets], they want single tracks. There was never a moment, until recently, when you could go to things and find tracks and buy a single track. The good thing about LPs and compact discs was that you bought the lot because you liked two tracks, and then discovered that you liked three of the other tracks even more. That’s the whole point of proposing a program and selling a program rather than a track.

If you do à la carte tracks, you tend to stay with the same situations all the way through. You know what you like and you buy it, but you are not diverted by discovering something. I think presently the recording world is singularly unfriendly to the idea of a collected edition of lieder.

Those great big ’78s—which weighed a ton—were replaced by the LP. The ’78 people felt aggrieved by the LP’s appearance, and the LP people felt aggrieved by the CD’s appearance, and now the CDs people like me feel aggrieved by the fact that it’s all downloadable tracks and an uncertain future. If you don’t have faith in the greatness of the repertoire, and the eternal factor that Schubert lieder represents one of the monuments of Western civilization, if you can’t have confidence that the music itself is good enough to survive and demand to be heard… Well, if I was to not have confidence in that, it would be to admit to having had a wasted life. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.