When he was 16, Wolf Biermann emigrated from his hometown of Hamburg to the German Democratic Republic. The year was 1952 and the young man, whose father was a staunch Communist and killed in Auschwitz, was welcomed in the East. Less than 25 years later, Biermann, now a rock star—his apartment, dubbed “the waiting room for the world revolution,” was a meeting point for many of East Germany’s intellectual and cultural elite—was stripped of his citizenship while on tour in the West. He learned about it on the radio.

For many of Biermann’s friends and colleagues, what happened next was a turning point. Their faith in Communism had gone hand-in-hand with criticism of the East German regime, but now their voices had risen louder in protest. They were met with increased surveillance and arrests. Amid all of this, one story as recounted by musicologist Elaine Kelly in Composing the Canon in the German Democratic Republic: Narratives of Nineteenth-Century Music stood out as I read it last December:

Following Biermann’s expulsion from the GDR in 1976 and the exodus of many of the GDR’s leading artists in his wake, another 19th-century winter’s journey, that depicted in Franz Schubert and Wilhelm Müller’s “Winterreise” emerged as an anthem of disillusionment. Writing in 1995, [author] Christa Wolf reflected on the contemporary resonances that the work had acquired for her and the philosopher Wolfgang Heise as their dreams for the GDR evaporated. Recalling a recording of the song cycle that Heise had given her as a present, she explains that it was intended as a “form of consolation … (‘we are not the first’) but also as a hidden clue as to how art can nevertheless survive.”

Like Schubert’s winter wanderer, Wolf Biermann came to East Germany a stranger, and a stranger he departed. It’s a familiar feeling to those of us who entered the voting booths with an air of significance on November 8, 2016 only to ride the subway in stone-faced silence on November 9. Such a peripatetic sense has carried through the better part of 2017.

Perhaps that’s why, in the last nine months, New York has been the setting for at least three dramatic reimaginings of “Winterreise.” In December 2016, Dutch composer Boudewijn Tarenskeen’s adaptation of the work, dubbed “Winterreise for the 21st Century” was performed by singer-songwriter Wende and pianist Gerard Bouwhuis at Brooklyn’s National Sawdust. Amid countless traditional presentations of the work in between, a choreographed version by Amy Seiwert’s Imagery was seen at the Joyce Theater following its premiere in San Francisco. Most recent was the Lincoln Center stop for Ian Bostridge’s tour of “The Dark Mirror,” which explores Hans Zender’s reworking of Schubert through a staging by Netia Jones.

Part of the Mostly Mozart Festival, “The Dark Mirror” played at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater, a hall situated in the Time Warner Center’s shopping mall, which in turn is located in Columbus Circle, which in turn sits across the street from the headquarters for Trump International. Coming out from Bostridge and Jones’s haunting, Weimar-esque staging into the glaring sunlight of a late Sunday afternoon, I scrolled through my phone for updates on the attacks in Charlottesville. At the bottom of the escalators, I looked up and found myself confronted by the two obelisks standing for what I considered to be two of this country’s biggest blights: on the right, a statue of Christopher Columbus. On the left, Trump Tower. It was a singular moment in time that Schubert and Müller could have pulled apart into its own 24-song cycle. “We are not the first,” I thought.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Of course, neither Schubert nor Müller were the first to experience from personal deprivation against a background of political winter. Still, they suffered keenly. Wilhelm Müller was 26 when he published “Die Winterreise” across two installments in 1822 and 1823. Six months before he sent the first half of the poems to his publisher, Müller’s father died. As the sole survivor of seven siblings who also lost his mother at 14 and was battling what many now believe to be consumption, it would be difficult to imagine Müller not haunted by some specter of death as he wrote the texts.

Outside of his own interior landscape, Müller was also writing in a time of European political upheaval. Greece was fighting a war of independence against the Ottoman Empire—a cause that Müller so supported that he became known as Griechen-Müller. And on the home front, Germany was in its so-called Age of Metternich (named for the then-Chancellor of Austria), a period between Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 and the March Revolution of 1848 that was rife with censorship, especially in areas such as the press, freedom of speech, and academics.

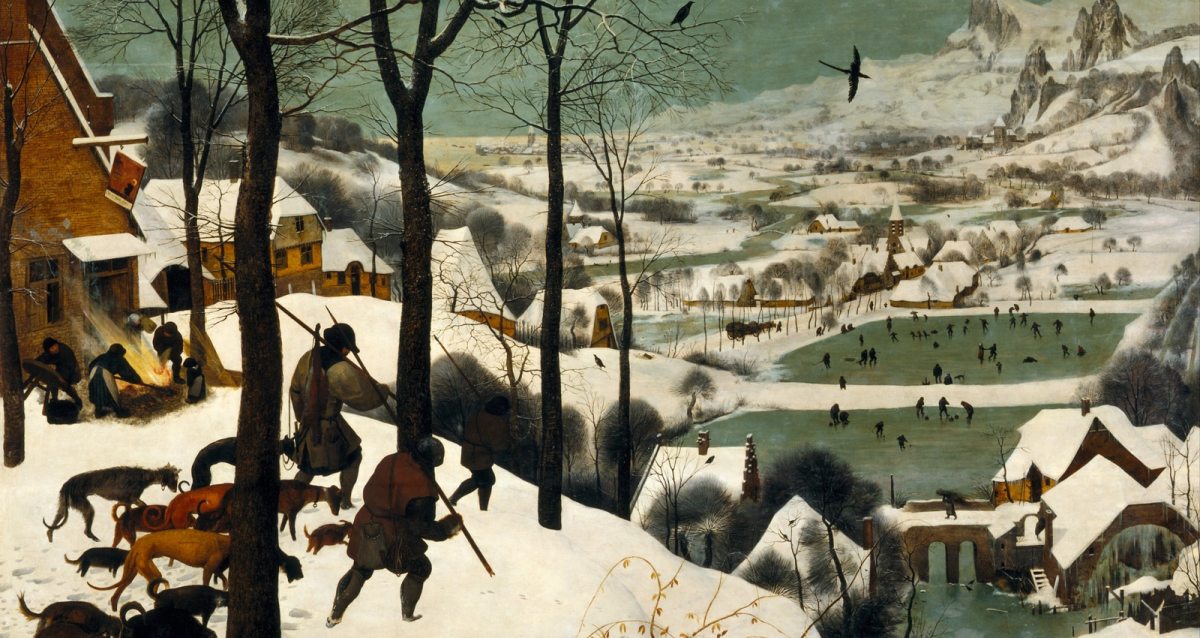

The late German musicologist Reinhold Brinkmann paints this era as the winter of discontent for artists such as Müller and Schubert. “The wanderer’s aimless journey in an impenetrable landscape,” Brinkmann wrote in 2005. “That is, a disparate world dominated by powerful, impersonal, anonymous institutions where death prevails—this journey represents the situation of the individual demanding freedom and self-realization within the repressive power-exercise.”

Such consolation Christa Wolf described in receiving a recording of “Winterreise” from Wolfgang Heise was mirrored in Müller’s own diaries. “Be consoled in the assurance that the poems will find a kindred soul who hears the melody in the words and who gives them back to me,” he wrote in 1815.

Also in 1815, Metternich passed the Marriage Consent Statute, which required male citizens to apply for a permit to marry. Approval for such a permit was determined by salary, and the following year Schubert applied, and was rejected for, a job that would make him exempt from the statute. “Man resembles a ball, to be played with by chance and passion,” he wrote in his diary the day after his rejection. “To a free man matrimony is a terrifying thought in these days: he exchanges it either for melancholy or for crude sensuality. Monarchs of today, you see this and are silent. Or do you not see it?”

There is something cosmic in these diary entries coming within months of one another, a spotting of kindred souls. It was in 1823 that Schubert agreed to set Müller’s poem cycle “Die schöne Müllerin” to music. Though separated geographically—Müller in Berlin and Dessau, Schübert in Vienna—the pair were both embedded in their social circles of fellow artists and philosophers, meeting in salons that may have served as their own waiting rooms for the world revolution.

In “Die schöne Müllerin” the directness of Schubert’s music was matched by the intricacies of Müller’s texts, the result being a song cycle that epitomizes the Romantic era’s fetishization of unrequited love among the linden trees. Schubert’s interest in setting cycles of songs (versus standalone lieder) led him to revisit Müller’s works with “Winterreise.” By then, the composer was also well into the syphilis that would eventually kill him at age 31.

“I find myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world,” Schubert wrote in 1824. “Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who in sheer despair continually makes things worse and worse instead of better; imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have perished, to whom the felicity of love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain at best, whom enthusiasm (at least of the stimulating variety) for all things beautiful threatens to forsake, and I ask you, is he not a miserable, unhappy being? ‘My peace is gone, my heart is sore, I shall find it nevermore.’ I might as well sing every day now, for upon retiring to bed each night I hope that I may not wake again, and each morning only recalls yesterday’s grief.”

And so enter the protagonist of “Winterreise”: A nameless hero who had been living with a girl and her mother. “May was good to me with many a garland of flowers,” he recounts. “The girl, she talked of love, the mother even of marriage.” Yet for some unarticulated reason, it is now winter and “love loves to wander…from one to another.”

He takes his leave in the middle of the night and enters into an odyssey of thinking and overthinking, mostly about death and desolation. Leaving one village, he roams the physical wilderness of winter and the metaphorical wilderness of heartbreak, devoid of any human interaction until the final song, “Der Leiermann.” In between are 22 scenes painted with the lingering detail and unhurried accuracy of a Tarkovsky film. A weathervane spins. A crow hovers in the sky. A leaf quivers on its branch. The frozen stasis of the scenery, despite the protagonists’ battle with himself, redefines the term “cold war.” The repression—be it political or personal—burns hot.

It’s the protagonist’s encounter with the Leiermann, the hurdy-gurdy man, that breaks the spell. A street musician, shoeless, grinding away without an audience. It’s here that our hero finds a kindred soul. The final lines of the poem are the hero’s hope that the hurdy-gurdy man hears the melody in his words and can give them back: “Strange old man, should I go with you? Will you to my songs play your hurdy-gurdy?”

One can only imagine that Schubert, revising this work on his deathbed, saw the duality in the hurdy-gurdy man’s character. His encounter with the protagonist marks the end of the cycle, but the beginning of the protagonist having a conversation that takes place out of his own inner monologue. He will follow the busker—or perhaps not. Perhaps the hurdy-gurdy man is a metaphor for death. Perhaps he’s no more or less than an itinerant musician.

The idea that the hurdy-gurdy man would answer “yes” to this final question and set the wanderer’s songs to music leads to what Ian Bostridge describes in his monument to his own “Winterreise” obsession, Schubert’s Winter Journey, as “the crazy but logical procedure [of going] back to the beginning of the whole cycle and start all over again.” One of the two ways Bostridge sees this as playing out is “with a notion of eternal recurrence in mind—we are trapped in the endless repetition of this existential lament.”

It is through repetition, we are reminded, that art survives. It survives through this same notion of eternal recurrence. “Art is at the end of the song and the cycle, ready for winter as a steward of liberated hopes,” concludes Brinkmann in his own study of the “Der Leiermann.”

“Come to Schober’s today, and I will sing you a cycle of horrifying lieder… They have affected me more than any of my other lieder,” Schubert had said by way of invitation to a friend for the first performance of “Winterreise.” When his friends were “utterly dumbfounded” by the “mournful, gloomy tone” of the work, Schubert retorted, “I like these lieder more than all the rest, and you will come to like them as well.”

Wilhelm Müller died in Dessau, Germany in Septemer of 1827, between the first half of the composition of “Winterreise” in February and the second half’s composition in October of the same year. A year later, Schubert died. On his deathbed, he was correcting the proofs for part two. It would be the peak of Romantic synchronicity if one of the final melodies he heard in his head was that of “Der Leiermann,” spinning his songs into the night.

The hurdy-gurdy man knows that he isn’t heard by anyone in the town. Yet he keeps playing, serving as a beacon for the kindred soul who eventually comes upon him. And so, too, has “Winterreise” endured as a beacon for artists and rebels. Thomas Mann quotes from “Der Lindenbaum” in the opening of The Magic Mountain. In Schubert’s Winter Journey, Bostridge links “Der Leiermann” to Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” West Germany used “Winterreise” as the codename of its search for members of the Red Army Faction, a metaphor in and of itself for the iciness between two opposing visions for society. Even the lieder nature of the works calls to mind the intimacy of a community bound together through art—the art song recital as a social gathering.

And then there’s Zender’s “Winterreise.” Written in 1993, less than five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and just two years after the collapse of the USSR, it is the centerpiece of Netia Jones’s “The Dark Mirror”—but not, in Jones’s view—a staging of the work itself. Rather, “The Dark Mirror” is a work of art about a work of art about a work of art, layering in Bostridge’s 25-year devotion to the song cycle.

“Ideas of mortality and the passage of time, our judgment of our younger selves and ideas of isolation, innocence and experience, are made literal and are illustrated,” Jones told me via email. The work matryoshkas in on itself with frames of reference to constantly remind us of those who have walked this snow-strewn path before us. And if we are not the first, then that begs the question of, “Why do we keep making this journey?” Or, as Jones puts it: “As time collapses, we are left with the question: What has changed, what remains the same, and what have we learnt?”

I tucked my program for “Dark Mirror” into my purse. I scrolled through photos of men in Virginia carrying flags emblazoned with swastikas, bookended by two towering homages to two hateful figures. I found myself asking the same thing. I wasn’t the first. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.