Filmmaker Sheila Hayman’s new documentary, “Fanny: The Other Mendelssohn,” premiered last month in London, takes as its subject Hayman’s great-great-great-grandmother, the prolific composer Fanny Hensel. The film provides the rare experience of viewing a documentary devoted to one woman composer, its thorough research portraying Fanny as both a musical genius who composed masterpieces and a woman oppressed by a man’s world.

After her 2010 documentary about Hensel’s brother, Felix Mendelssohn, Hayman searched for material to make a film about Hensel, and found it in the recent discovery of the composer’s “Easter” Sonata, a manuscript that many had mistaken as a work of Felix’s. Hayman and I talked about what it was like to work with an all-women crew, how she relates to Hensel’s artistic struggles, and why women artists need more “creative heroes.”

VAN: What was behind the choice to start the film with the Queen Victoria story, where Mendelssohn was forced to admit that the Queen’s favorite piece “by him” was really composed by his sister?

Sheila Hayman: It seemed like the most commercial thing to get people in with. We were delighted when [pianist] Isata Kanneh-Mason agreed to be in the film. When we got into Buckingham Palace—that room makes Mar-a-Lago look like IKEA. We thought, ”How can we not?”

We did our best to only work with women and to have women crews. I had a female editor and musicians. We arrived at Buckingham Palace with the first all-women crew they’d ever seen. As we were packing up exactly on time, having not made any marks on the carpet, the woman from the Royal Collection Trust, a PR person said, “We’ve never had an all-woman crew before. They’re very good, aren’t they?” And it’s true.

Working with women, you don’t get any of that kind of jockeying for position, that ego of, “This is my job. And that’s not my job. And this is your job.” Everybody just helped everybody else. One of the joyous aspects of making the film was the discovery of how nice it is to work with a team of women. No disrespect to the men who helped us along the way as well.

Filmmakers so often act as though a film had sprung fully formed from their genius intellect and hadn’t actually been propped up by hundreds of other people’s efforts.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

What is it about Fanny’s music that makes it worthy of a film?

I’m not a musicologist. But what I’ve been told by other people, and certainly what I feel, when I listened to it myself, is that… she was incredibly self-critical. She set herself very high standards. And she was set to very high standards by her lovely brother. She had this extremely thorough grounding in music and obvious talent. Her adventurous spirit and her passionate nature were able to be expressed in a way that Felix couldn’t because she didn’t have to worry about the critics. (Though this idea that he was superficial is nonsense in my view. He obviously felt things very deeply, which you feel if you listen to his last string quartet or his other music.) All these things, combined with Fanny’s absolute love of music and her need to express lots of different things, is the reason why Fanny Hensel is really top-rate music. It’s first-class music, even though most of it is on a very small scale.

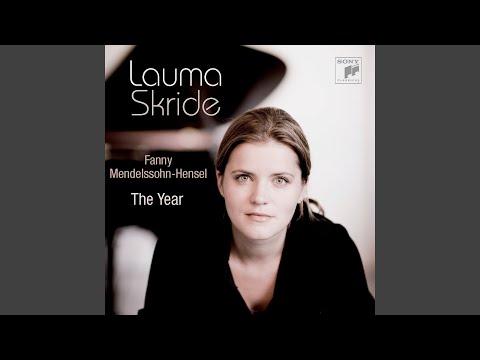

It’s as good as anything written by any man. If you look at “Das Jahr” [“The Year,” Hensel’s 1841 cycle of 12 piano pieces] for instance, it’s over an hour of incredibly complicated, musically, harmonically, and grammatically connected music that expresses every possible emotion, and is extremely virtuosic and demanding on the player. I don’t think that you can find anything better in the canon of piano music. I think it is a masterpiece. It’s extraordinary and invigorating.

Fanny just refers to it once in a letter to a cousin: “Oh, it’s a little thing I’m doing to entertain myself. I suppose it won’t go anywhere.” And you want to hit her! But she must have known how good it was. Unfortunately, because it’s so ambitious, difficult and demanding, it’s very rarely performed or recorded. But one hopes that will change.

Do you see anything of yourself in Fanny, especially since you’re a descendant?

Obviously, I wouldn’t attempt to compare myself to Fanny because she had an incredible creative gift, which I obviously don’t have to that degree. I think there are quite a lot of women nowadays who have none of the misgivings about putting themselves forward, or being thought to be pushy, or advancing their talent or promoting themselves.

I am like Fanny in the sense that she didn’t want to be difficult. She hated the idea of being thought arrogant. She wanted to have a happy family life, children and parties. I suppose I do see parallels. [I] would rather be not known at all than thought unaware of my own deficiencies or the deficiencies in my work.

Fanny absolutely leapt on all the negatives that Felix pointed out in her music. That’s one of the great tragedies of her life, and one of the reasons why she wrote only [one piece in] so many genres. She wrote one string quartet, she wrote one piano trio. She did have this rather distressing tendency; the minute somebody says anything that makes you seem foolish for having tried, it’s quite difficult not to be put off by it.

How much of this had to do with the social pressures in Hensel’s time?

You internalize the external, don’t you? If your model of a creative genius is somebody tormented, an antisocial stinky person with no manners and a lot of aggression, like the big grand Beethoven—if that’s a creative genius, it’s not you. An artist’s hero is not somebody who thinks about other people or puts dinner on the table or is nice to her husband. And so you think, “I don’t have a gift for it,” because women aren’t meant to do that stuff. They were told it over and over again. It’s kind of hard not to believe it.

But that’s the conflict. There’s this voice inside you that says, “yes, I want to express this and yes, I want to write this,” and when you play it to yourself, you think, “Actually it’s quite nice.” She had this constant paradox. They were constantly trying to fight between what they were told from the outside and what they felt from the inside. And that kind of conflict never went away.

I think Fanny wanted to do whatever she did within the limits of what was acceptable. Her upper-class nuance means nothing to us now, but she had the extra pressure of being very visible and very Jewish.

It’s really hard to imagine the emotional, psychological, and physical constraints that she was under. Imagine how, in those conditions, having a piano—this great big beast of an instrument that you play really loudly and could pour your sadness and your rage and your hope and your longing and your love into—it must have been an absolute godsend. Fanny was able to play on a metal frame piano, the Erard could take a lot of battering. It really was a huge expressive outlet for her.

Do you find some of these obstacles are still true today?

I don’t think I’m a good model, because there are so many complicating factors in my particular case. But now, thank goodness, there are lots of young women who are not being put off by it at all. The obstacles are much more practical these days, which is that women on the whole don’t have as much money given to them. As composers, they’re still not treated as bankable talent in the way that men are. And therefore they’re not able to command the budgets and the resources that men are, and therefore they tend to write smaller works, and therefore they tend to be pigeonholed as people who write smaller works, and therefore it’s thought that women write smaller works. There are a few women who are distinguished enough and celebrated enough to actually be funded to write big works for big forces, and I hope that there will be more in the future. If you roll together two of the very few really positive developments of the last five or six years, #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, I don’t think it’s possible to go back from either of those. It may be that not enough progress has been made. But I think it’s no longer possible to claim that people of color or women are intrinsically less worthwhile and can be pushed around in the way that they were before.

In the film, when Chi-chi Nwanoku, the founder of Chineke! [Europe’s first majority Black and ethnically diverse orchestra] said that their first rehearsal was the first time that any of the musicians had not had to think about what color they were, in the context of playing their instrument or pursuing their career, it was really shocking. And I think it’s absolutely true, unfortunately, in this country, and I think probably in other countries as well.

To be a creative artist is essentially to insist on your right to play. You’re playing with paper, you’re playing with paint, you’re playing with sound. It’s open ended, it’s uncertain. To insist on your right to play above your duty to do all those other things that life demands of you—I think very few women have got the nerve to do that. Whereas I think a lot of men do.

Look at the film directors, gargantuan old men who should have given up making films years ago, who are still given money to make films because they’re considered to be geniuses, or they’re considered to be heroes, or they’re considered to have a unique vision. Look at how few women are in that category. Is it because women don’t have the same talent? Is it because there’s some natural predisposition of women to have less ability to create things than men? I don’t think so.

This distinction between being a powerful woman enabling other people’s creativity and being a bankable creative yourself… It’s really, really difficult, even though I’ve learned to do that. I just hope that will change because I think that we need more women role models. For women to want to be those creative heroes. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.