Whether it’s Julius Eastman’s “Prelude to the Holy Presence of Joan of Arc,” Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis,” or Anthony Davis’s “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X,” listening to Davóne Tines sing is like watching rock climber Alexander Honnold free solo up El Capitan: You’re struck by the raw power and voltage of his stentorian baritone, which accentuates—rather than eclipses—the gravity of the works he scales. His recent performance of “Prelude” sent the rosary-like repetitions of Eastman’s text echoing against the octagonal walls of Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church with evangelical force.

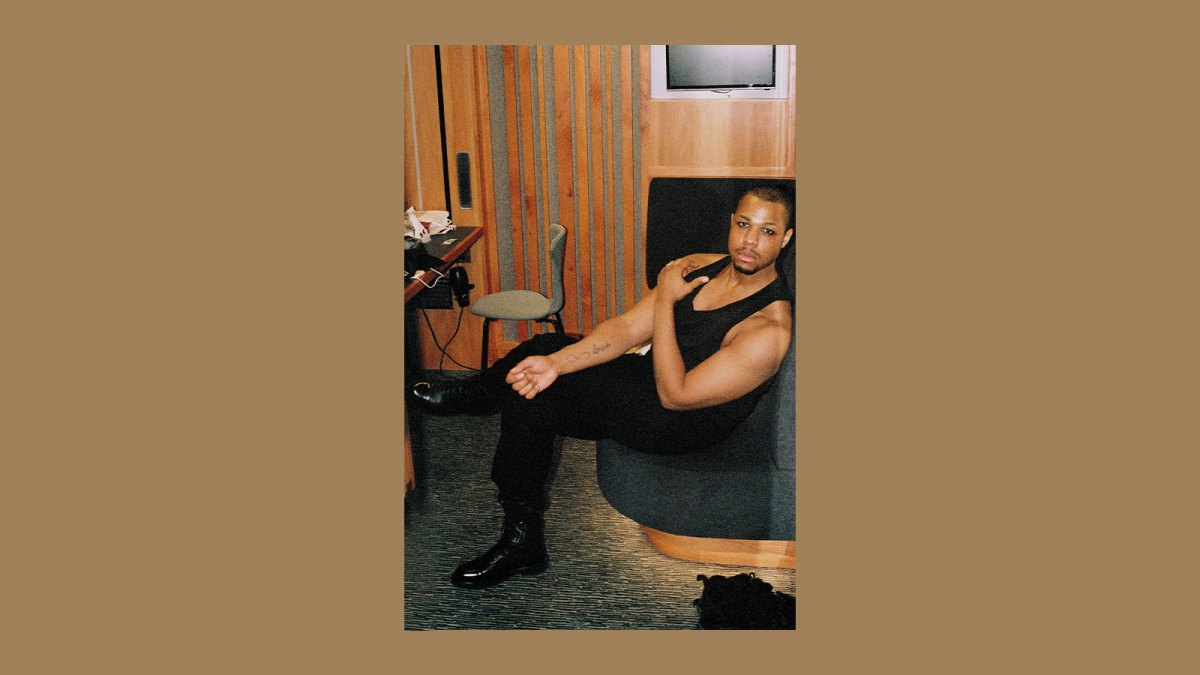

Offstage, Tines is more soft-spoken. When asked a question, he takes a moment to pause before responding in a philosophical paragraph that often wanders into sociology (which he studied as an undergraduate at Harvard before doing his master’s at Juilliard). I met with Tines near the Kaiser Wilhelm church, where he was rehearsing a program with the Berliner Singakademie that interwove several Eastman works with three movements from Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis.” It was part of a concert schedule that, as we were sitting down to lunch, he said had kept him on the road for 300 out of the last 365 days.

VAN: Really, 300?

Davóne Tines: Yeah, I think in the past week I’ve been in five hotels. I’m co-creating an exhibition for the Cooper Hewitt, which is part of the Smithsonian; it’s part of their “Home” Triennial. And I should have finished writing by now an essay about that, but today, I had new inspiration on writing the essay. I think I’m just going to describe what my hotel life has been this past week, and describe how important a concept of home is in the midst of all of that.

Do you end up doing what a lot of other musicians do: take pictures of your hotel room doors so you remember what room number you’re in?

You know what, I should start. I’ve been traveling like this for almost a decade, and I’ve been really good about it. But lately, in a week like this, being in three hotels in four days, I’m just straight-up forgetting the room number. You seem insane [at the front desk] when you’re like, I really don’t know. Today, I’m in 605. [Laughs.]

In your New Yorker profile, you talked about learning how to build a recital program at Juilliard and questioning the format. How did that questioning evolve into the type of programs you do today?

In classical music, there seems to be a lot of staid structures that things have existed in. And those structures have existed in ways that were outside of question or critique. I find, largely, when you present a question, a lot of times people think it’s an assertion that the thing should not exist, as opposed to an honest inquiry into understanding why and how something exists.

I’ve always questioned the structures that I was presented with. Because I wanted to understand them, not necessarily discount or break or reorganize them. But, by the very nature of understanding how something exists, you have to take it apart. And I think engaging existing structures within classical music invites us to understand what their purpose or their goal is. So in looking at the recital, you realize that that structure comes from a distillation of what was a more social or open musical event—a salon concert or someone deciding to sing some songs for a group of people. And then that became formalized over time into the structure through which solo classical instrumental or vocal music is shared within the larger classical music institution.

It’s also incarnate as a rubric for how students learn, but [with] no real refreshing of understanding within modern pedagogy of why those structures are the way that people are being taught. By questioning an existing structure, I want to understand why it exists and where space has been made in that structure for me to exist or not. And what I found more often is that the structures that make up classical music presentation and also the rubric from which I was being taught within those structures were ignorant of my broader context, not inviting repertoire from places I was more connected to in terms of lineage or even musicality or musicology. And, again, it’s not to denounce the structure. It’s to say, “Oh, it seems like at its most basic incarnation, [the recital] was meant as a personal invitation to share something, but the calcification of what that means has meant the exclusion of certain parts of people’s identities,” which I don’t think was the original intention. Maybe it doesn’t even make sense to try to conjecture what the initial intention is.

Maybe a simpler way to put it is: My life is composed of a complex interweaving of aesthetics and realities, as everyone else’s, and thus my musical programming needs to simply reflect that.

I was going to ask how studying sociology as an undergrad influences the way you program, but I feel like you just answered that.

[Deadpan:] Yeah, people are really complicated. [Laughs.] And really nuanced, and come from so many different things, and when we try to boil it down into structures—as sociology tries to—we only do that as a means of trying to understand more specifically the vectors and nuance of an individual. I mean, now it seems commonplace to talk about intersectionality, but until my sophomore year of Harvard, I’d never heard that term before, and it wasn’t a commonplace term… So to just learn that someone’s identity is made up of the intersections of all of the different vectors of their existence seemed revolutionary, eye-opening and groundbreaking for me personally [at the time].

And I think in our contemporary way of engaging art socially in the past five, if not ten years, being respectful of those individual vectors in public places, where those things have a confluence, has become more front-of-mind for the general public. Which I think is a very positive motion, and further to why a program like this one [with the Singakademie] would exist: Something that is saying, “Oh, here’s a bastion of a particular train of lineage within classical music, and here’s something being recognized as counterbalancing or similarly important,” and placing those two things in conversation. It’s exactly what should be done in order to rethink how value is assigned to expression from different contexts, and how those values can bolster each other by things being put in conversation. Not necessarily to contend with each other, but to actually balance one another. That’s kind of what equity looks like.

This program with the Berliner Singakademie isn’t one that you put together. But the combination of the Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei from Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis” and the selections of Julius Eastman, and how those two composers work in conversation with one another, feel like very “you” things.

We shouldn’t have to say that programming both an old German white composer and a “relatively” younger Black composer is “revolutionary,” because both of their works are incredible and both of the works bear the mark of… genius, if we want to go there. But it is, in effect. It could be seen as an effort to add to the psychological equity within culture; to put it within people’s minds who would never have put those two people on the same level. And to do so at such a scale.

That’s partly also what makes me so excited; it’s really a statement. Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis” is a piece of such incredible scale. You could almost say, from certain perspectives, an absurd scale: the amount of musicians needed, the scale of the musical phrases… It’s huge, and it’s really juicy. The works of Julius Eastman that are solo a cappella works essentially, aside from “The Holy Presence of Joan of Arc,” counterbalance these things. It’s a daring statement. It’s a daring invitation. To suggest to people that this is what balance looks like.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

In the summer of 2020, Tines curated a video performance, “Eastman Homage,” for the Rockport Music Festival in Massachusetts. In the video, Tines sings Eastman’s “Prelude to the Holy Presence of Joan of Arc,” which also opened the Singakademie program, cut with intertitles (also by Tines) that gave background to Eastman’s life and artistic philosophy.

“Eastman paired his genius compositions with bold titles that explicated the realities of his race and sexuality: ‘Evil Nigger.’ ‘Crazy Nigger.’ ‘Nigger Faggot.’ ‘Gay Guerilla.’ ‘If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich?’” Tines wrote in the intertitles, adding, “The language was so acidic, it ate away at the concert hall universe, and was perhaps a fitting gesture for someone who saw as much rank hypocrisy as opportunity within its walls; and his over integration of his identity into his work, especially his ‘radical Blackness’ was seen as ‘too political’ and ultimately unpalatable for even the avant-garde.”

Festival organizers had asked Tines to edit the titles, but Tines—citing Eastman’s own specific instructions that they not be edited—declined, and withdrew the video from the festival program, sharing it instead on his YouTube channel.

During the pandemic, I remember you had come up against concert organizers over the mention of some other Eastman titles.

I think it’s important for people to remember there’s nuance within the idea of fear. Just because something feels uncomfortable doesn’t mean that it’s ultimately unsafe. The presentation of something that is seemingly outside of their identity, or not presenting a direct imminent threat to their personal, physical being… It’s important that we don’t discount engaging with something just because it makes us feel uncomfortable. Uncomfortability is not the same as unsafe.

It feels like part of the ongoing ebb and flow of the debate around whether art should be political or a haven from politics.

I wish people would realize that is inherently a fallacy.

Can you say more about that?

There’s no such thing as nonpolitical anything. Aside from there not being nonpolitical art, there’s no such thing as “nonpolitical,” because the moment something exists in the broader public for people to engage socially, it has the potential to be galvanizing or divisive. People can ascribe any sort of larger intention to it by the fact that it’s just an object visible in the public.

Art, by its very nature, is a reflection of the world that it is in.… If art is about anything, it’s about people’s lives. People’s lives are political by the very nature that we exist in the world. Another way to put it is, if there is art that is solely entertainment, then that is not art that I’ve ever been a part of. I grew up singing in the Black baptist church. Yes, that is music that is seen as art, but it’s music for a reason. It’s music that has a function. If someone is singing a mass, that was created in a large religious context that’s existed for thousands of years in a certain practice. Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis”: that piece is not meant for entertainment. It’s a mass text. It is a very clear narrative, taken from a very clear context, and delivered at a very specific scale. It has political context because it has religious context.

Do you remember the first Eastman work you heard?

It was the first Eastman work I ever did, which was “Prelude to the Holy Presence,” and that was because of Jonathan Hepfer, who is the artistic director of the Monday Evening Concert Series in Los Angeles. I had an invitation from him by way of Peter Sellars to sing “Prelude to the Holy Presence of Joan of Arc.” And at that point, I had never heard of Julius Eastman. I consider Jonathan a genius because he was basically the first person to program a portrait concert of Eastman before the whole revival. Like, the concert I’m doing here [in Berlin] would not exist if Jonathan did not program me singing the “Prelude” in 2017.

And that was a huge revelation because, yeah, I didn’t know that a Black, gay, minimalist, composer, singer, and pianist had existed and was making work that was directly interrogating his social context.… That “Prelude” began my understanding of Eastman.

After that first concert, was it a moment of, I need to find out everything about this guy, or did it just happen naturally that more invitations came in to do his work because you knew it?

It became kind of a natural snowball. The other important part about the reawakening of understanding and engagement with Eastman is that the repertoire itself has continued to reveal itself, evolve, and become transcribed or widely available. It’s not like there’s an existing catalog just sitting there, waiting to be performed. A lot of scores were done away with, a lot of scores were held by individuals that needed to be brought together and be kind of properly taken care of. Even the first piece that I did, the “Prelude,” there wasn’t a score. It’s essentially— as a lot of Eastman’s pieces are—a very organized improvisation. There was no score that existed aside from other people’s attempts at representing the piece in a score form. So my first performance of Eastman was also a musicological, almost pedagogical dive into who this person was in order to realize a 13-plus minute solo a capella piece from no score and only the composer’s recording. I got to know him in a very kind of deep and intimate way out of necessity; not even out of curiosity, but out of the need to make something functional to perform. I had to get to know those contours of what his work as a composer was. That’s led to becoming a part of a growing community of musicians, scholars and colleagues who want to grow that work. It’s kind of an ever-expanding journey and circle of people that are upholding and moving the work forward.

Practically, how does that look for a singer where you have this work and no score?

I had to listen to the piece beyond the amount of times that I can count, just to try to start to understand what it was, understand how I could represent it. So that kind of does play on my training as a pianist and a violinist; music theory training to one, try to grasp it theoretically, and then, two, try to transcribe it into something that, three, I could perform replicably.

So I listened to it a ton, and I started to understand that it might be in a certain time signature and a certain key signature, and what the overall structure might be. And then where there was flexibility within that structure, that was a really important point. At first I was transcribing in as much micro-detail as possible, to the point of quarter tones. But then you realize he’s not thinking that way. He’s just a person singing a song, which would actually have micro variations. So I kind of had to stop trying to look at it with that kind of a lens and just see the structure of it at a different level.

I imagine it’s kind of like when you’re learning to drive and your hands are firmly at ten and two, and you’re doing everything as it looks in the diagrams, and then as you get more comfortable as a driver, you can relax a bit more…

Yeah, if you’re a new driver, you might look at every falling leaf as something that you should avoid, or be cognizant of. And that’s what I was doing. And then later I realized, Oh, I actually need to just be aware of where the trees are, not the individual leaves. Because the individual leaves are just happenstance events of just walking through the larger tenets of the piece, which are the musical phrases in quarter notes, in half steps, and trying to surmise what a live performer is doing in that way. Meaning it’s also not listening. I mean, you couldn’t listen to someone sing “O, mio babbino caro” and do a clean transcription of it that looks like what’s in the score, right? It’s an interpretation of something that is more nuts and bolts.

So at a certain point, you have to hear through the interpretation of the piece in order to distill it down to its base material. So that action done over the course of four weeks was my crash course in understanding who this person was psychologically and methodologically, and then also in a deeper and emotional way. A part of the performance practice of Eastman that is inescapable is how he writes organically or for the organic nature of the performer, meaning the prelude starts out very steady, if not energetic, and by the end, after ten-plus minutes, it becomes a lot lower in register and slower. It sounds as if the performer has become tired. The piece is designed to do that. The actual arc of the piece is designed to mirror the energy. The performer will have to sustain the piece, and that’s part of the genius. It’s not just, Well, here’s a long thing, I hope they get through it. It’s written with a very clear eye towards supporting the natural growth and decay of a musical event, or of an event in someone’s life. And that’s true for the solo prelude. That’s true for larger works like “Gay Guerilla,” that last close to an hour. There’s just so much to be gleaned by actually understanding how his pieces exist. They are a dialectic to how he saw and engaged the world.

With both your “Eastman Homage” and another video, “Vigil (An Exercise in Empathy),” you’ve done something beyond just setting up a camera and singing—which a lot of musicians were forced into doing in the last few years. With the intertitles, it seems you really inhabited the medium, creating something between a meditation and program notes. What led to that?

The pandemic. Goodnight! [Laughs.]

One thing I kept finding myself saying at the top of and throughout the pandemic was that the phone screen or the laptop screen is our proscenium now, and we shouldn’t act like it’s not that. So I became very allergic very quickly to just recording myself performing because there is an actual practice and history of representing performance on camera, and I think most of popular culture has figured that out. And so there are things to learn from as opposed to ignoring an entire artistic lineage by saying, I’m going to represent a performance that normally would take place in a theater by filming myself in a living room.… I guess my thing is, the work that I do in front of people is extremely considered and exists within contexts that are very established and maintained. I walk up to a stage that is in a concert hall: that is an extremely considered space in many, many different ways, from how it’s designed to how it’s maintained, to how it’s inhabited, to how the rituals within it occur. Let’s not ignore that. So if I’m to replicate that in a different medium, as much intention as to creating the original space should be made for how that presentation is to occur again.

“Vigil” came out of a film I made for the National Education Association online award ceremony. In order to do that, I filmed myself with a professional film crew in a theater in Washington D.C., recorded a live performance that would be shared with a very private group of people. I received the raw footage from that professional recording, and formed it into the video. So what you see of my face was professionally made. The consideration, with slides and texts and timing…that’s just me with a computer, just being intentional about the use of resources. I made “Vigil (An Exercise in Empathy)” with the intention of asking people to become physically present so that they could emotionally receive something that they normally wouldn’t. And so I used all of the resources available to me at that time: camera and editing on a computer, and also intentional thought about how the audience psychologically approaches the song to create that piece of media. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.