When he wasn’t busy scoring for the likes of Sergio Leone, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Marco Bellocchio, Bernardo Bertolucci, Elio Petri, Brian De Palma and Terrence Malick, Ennio Morricone could be found hunched over a chessboard. He was a good enough player to hold former world champion Boris Spassky—who famously lost to Bobby Fischer in 1972—to a draw (an achievement Morricone modestly attributed to Spassky not trying too hard). Chess was Morricone’s lifelong passion, rivaling music, the family trade he entered as a matter of course. In a Paris Review interview in 2019, he waxed philosophical on the links between music and chess: notation, themes, patterns, counterpoint—which, taken to its logical extreme, functions exponentially—concluding that music, chess and mathematics were creative endeavors, relying “on graphical and logical procedures that also involve probability and the unexpected.”

Or, in a word, “chance.” Curiously, he leaves beauty out of the equation; and yet it was the sublime, meaningless beauty of the game that captivated me in my youth. My idol was not my hero, Bobby Fischer, but José Raúl Capablanca, whose games are revered for their clarity and elegance—Sergei Prokofiev compared “Capablanchik” to Mozart.

A list of musicians partial to the royal game includes Jean-Philippe Rameau, Fryderyk Chopin (who made his own pieces), Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann (who taught Brahms the moves), Antonín Dvorák, Modest Mussorgsky, Enrico Caruso (who counted Yugoslavian master, Boris Kostić, in his entourage), Pablo Casals (friend of Capablanca’s), Fritz Kreisler, Moriz Rosenthal, Mischa Elman, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Erik Satie, Sir Thomas Beecham, Prokofiev, Feodor Chaliapin (yet another friend of Capablanchik’s), Artur Rubenstein, Gregor Piatigorsky, Paul Robeson, Dmitry Shostakovich, Vladimir Horowitz, (who used to play Isaac Stern), Yehudi Menuhin, John Cage, Matthew Bengtson and Maxim Vengerov.

The list of chess worthies who excelled at music is shorter but no less impressive: the greatest player of the 18th century, François-André Danican Philidor, composed operas when he wasn’t playing for stakes or giving blindfold exhibitions.

François-André Danican Philidor: “Tom Jones”

“Blaise le savetier”

“Air d’Ricimer” from “Ernelinde, princesse de Norvège”

Like Bach, Couperin and Scarlatti, Philidor came from a family of musicians, his father an oboist and keeper of the king’s music for Louis XIV. The promise of chess, however, lured Philidor to Paris and the game’s Mecca, the Café de la Regence, where he played, among others, Voltaire, Casanova, Benjamin Franklin, Rousseau (a fellow opera composer), Napoleon (a sore loser) and Robespierre (a worse, and more dangerous, loser). In London, Philidor met Mayfair’s resident tub of pork and beer, Handel, who praised his setting of William Congreve’s “Ode to Music.” His opera, “Tom Jones” (after Henry Fielding), was the hit of the Haymarket in 1765. A few years later, “Ernelinde, princesse de Norvège” enjoyed success at Versailles, earning him a royal pension.

Philidor, however, died in exile. Despite the enduring relevance of his chess manual, “Analyse du jeu d’échecs,” most of his games—and compositions—have vanished into the mists of time. What survives, though, exemplifies the cheerful facility of the pressed but painstaking freelancer, an artist in spite of himself.

Sergei Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Major

“Dance of the Knights” from “Romeo and Juliet”

Piano Sonata No.7 in B-flat major (performed by chess fanatic Sviatoslav Richter)

According to Polish grandmaster Savielly Tartakower, Prokofiev played chess at the level of master. Among the greats Prokofiev defeated in friendly games were Capablanca, Emanuel Lasker (world champion 1894–1921) and Akiba Rubinstein. Prokofiev and David Oistrakh played a ten-game match at the Master of Art Club in Moscow in the late 1930s. (Oistrakh was trailing when he suddenly had to go on tour.)

“King David” was a Soviet category one player, essentially master level. What better calling cards, then, than the concerti Shostakovich composed for him?

Dmitry Shostakovich: Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor (David Oistrakh, Staatskapelle Berlin, Heinz Fricke)

Violin Concerto No. 2 in C-sharp minor (David Oistrakh, Moscow Philharmonic, Kirill Kondrashin)

Like many a Russian of the old school, Shostakovich acquitted himself well on the board. In adolescence, he unwittingly lost to future world champion Alexander Alekhine. “An honourable loss,” Alekhine said. (He was not a man noted for acts of charity.)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Sonata for Two Pianos in D, K.448; and Camille Saint-Saëns: “Variations on a Theme of Beethoven” (Mark Taimanov and Lyubov Bruk)

Darius Milhaud: “Brazileira” from “Scaramouche” (Taimanov and Bruk)

Mark Taimanov is best remembered as a casualty in Bobby Fischer’s inexorable march to the world title in 1972, losing 6-0. This crushing defeat cost him the privileges that came with being a Soviet grandmaster; “I still have my music” was all he could say. (His privileges were partially restored when Fischer repeated the feat in the next round, destroying the Danish grandmaster Bent Larsson.) A prodigy in music and chess, Taimanov entered the Moscow Conservatoire in his early teens and received chess lessons from grandmaster and future world champion Mikhail Botvinnik. After his studies, Taimanov formed a successful musical partnership with the pianist Lyubov Bruk, his first wife, touring the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Though his musical career faltered with their divorce, Taimanov continued to play chess and even competed successfully at the senior level.

Giuseppe Verdi, “Di Provenza il mar, il suol” from “La Traviata” (Mark Taimanov and Vasily Smyslov)

Which brings us to Vasily Smyslov, a player in the Capablanca line. A tall, soft-spoken figure, widely admired and respected by his peers, Smyslov would on occasion favor his fellow players with a medley of song between rounds, often accompanied by Taimanov on piano. In this Russian bill, Smyslov slips in a little surprise: Verdi’s “Di Provenza il mar, il suol” from “La Traviata” (in Russian). The title of his autobiography translates to In Search of Harmony.

Franz Schubert: Piano Trio in B-flat Major and Felix Mendelssohn: Piano Trio in D Minor (Artur Rubenstein, Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky)

The members of the short-lived “Million Dollar Trio,” Artur Rubenstein, Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky, were all avid chess players. Piatigorsky and his wife, Jacqueline—also a strong player, who competed in women’s tournaments—funded the Piatigorsky Cup, won by, among others, the Estonian genius Paul Keres, world champion Tigran Petrosian, and Boris Spassky.

Erik Satie: Music for the film “Entr’acte”

Among other eccentricities, Erik Satie spent hours composing chess problems. A highlight of the only film he ever scored, René Clair’s delightful “Entr’acte” (an interlude taken from Francis Picabia’s and Satie’s ballet, “Relâche”), is a rooftop game between Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp (whose chess career is well-documented). Satie also appears at the beginning of the film, the bowler-hatted gentleman who sets off the whole spectacle by gleefully firing a cannon.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

John Cage and Marcel Duchamp: “Reunion”

John Cage and Marcel Duchamp both gave free rein to the principle of indeterminacy in their work, and its boon companion, chance. (Cage preferred the term “randomness.”) Together they collaborated on a multimedia project that combined music and chess, playing a game on an electronic board operated on aleatory principles with the aid of a computer and a system of laser rays.

John Cage: “Chess Pieces”

“Reunion” was not Cage’s first essay on chess. Decades earlier, for a themed exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, he had concocted a rather Klee-like painting, “Chess Pieces,” where instead of fools and kings, musical passages occupy the squares. It’s unknown whether Cage meant it to be played, but Margaret Leng Tan managed to knit together a performable transcription.

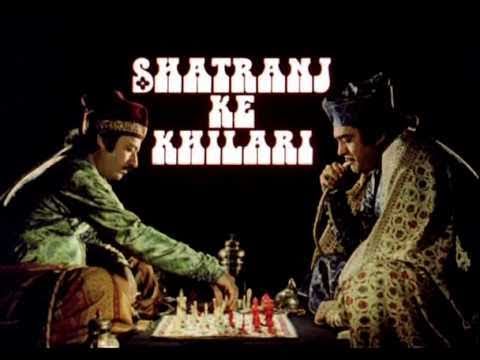

Satyajit Ray: Film score for “The Chess Players”

Satyajit Ray was a film composer who also happened to be a film director. I do not know whether Ray was as talented a player as Morricone, but “The Chess Players” (1978) is a gem, featuring a pair of patzers content to let the world go to the dogs so long as they can squeeze in one more game. In India, we’ve also come full circle, to the land where chess began more than 1500 years ago. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.