The reality outside the virtual reality is this: a blindingly sunny pre-fall day on Glasgow’s South Side gives way to a dark, almost bare studio in Offline (formerly Glasgow Artists’ Moving Image Studios). The room is divided into two halves, each with a square, slightly soft, and pleasingly bumpy fabric covering, and a stool for audience members to sit on as they take off their shoes.

This is where I experience “Songs for a Passerby,” Dutch director Celine Daemen’s virtual reality opera. Instead of getting dressed up to go to the opera, I’m down to a t-shirt, jeans, and socks. My instinct is to crack a joke to the assistant who is guiding me towards the main event, but the atmosphere is too reverential. I am told that, once the performance starts, a grid should tell me if I am going out of bounds; if I remember to “follow the light,” I’ll be fine.

Then the headset is on, and I leave my reality.

“Songs for a Passerby” won the coveted Venice Immersive Grand Prize at the 2023 Biennale. After touring around the world for a year, its first UK run (at Sonica Glasgow) is the closest the VR opera film has played to “home” for Daemen, she tells me. As at a more traditional opera performance, a program provides notes from the creative team (Daemen, composer Asa Horwitz, VR art director Aron Fels, and librettist Oliver Hertier), a reprint of the “Eighth Elegy” from Rilke’s “Duino Elegies,” and a libretto broken into scenes.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

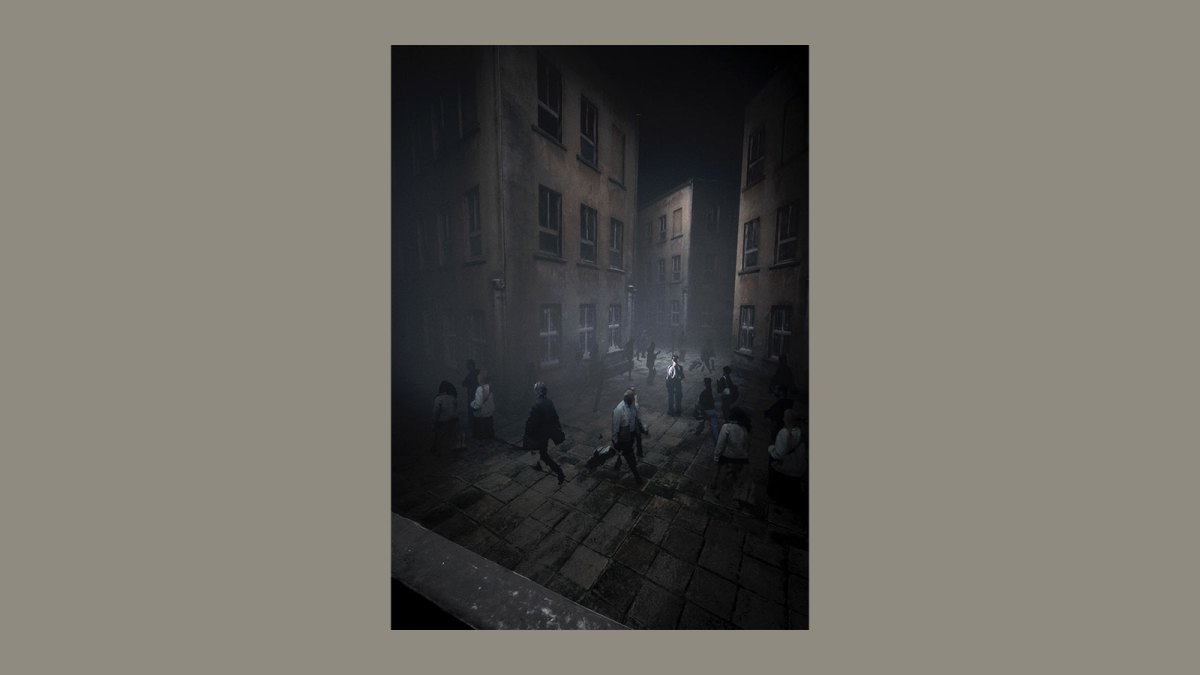

In “Songs for a Passerby,” each viewer is “both a body that is moving through space and a mind that is looking at it… You are both in the world and simultaneously outside it.” The transition between the dark, bare studio and the city flickering into view is all-consuming. The pre-show instructions are perfect; by following the light and a fox-red podenco dog—both evoking the wisdom of folk tales—I pass through a world of dark alleys, ghost-like apparitions, trains bearing commuters to undisclosed locations, and to the top of a city by the sea. The soft ground becomes dirt and twigs under my bare feet; along with the stray dog guide, the impression is one of a city being reclaimed by nature. Most startlingly, I see myself in another subway car, down on the street below, sometimes staring right back at me. When I wave my hand in front of my face, I see not my own arm but hers moving in the distance.

The music unfolds over the half-hour runtime in repetitions, combining Ukrainian folk melodies and echoes from the choral works of Hildegard of Bingen with mechanical and electronic noises evoking a city just beyond the bounds of this reality. Horvitz writes that “no difference is made between music and sound, everything exists on a spectrum from silence to noise.” With the all-encompassing visuals and lack of external noise, the effect is hypnotic, making a convincing, if artificial, case for a city’s aural synthesis of the organic and inorganic as its own orchestra.

With the libretto spoken and sung in various languages, supertitles are projected in “Songs for a Passerby” (as in the theater, opera remains a reading activity as well as a listening one.) The supertitles and the voices they translate are integrated into the scenery and sound design respectively: the former adds to the illusion of verisimilitude, and the latter decision sometimes makes it difficult to pick out one single voice among the score and city noises—which, again, merge.

Daemen’s work places viewers in a kind of duality between watching the world and participating in it, seeing themselves almost alarmingly impersonally, as others might. “It’s two-sided,” she tells me, highlighting the contrast between the body and the mind as you become a “spectator of yourself.” It is an effective argument against the kinds of dehumanization seen on social media through the trends of “main character syndrome” and treating others as “NPCs” (non-player characters, in video game parlance), even if this argument is made through computerized magic. And, if opera has always been predicated on watching and listening to others—often highly trained, immensely talented artists—seeing one’s peers and one’s self, in our shared mundanity, is strangely moving.

Sonica Glasgow is an 11-day festival dedicated to audiovisual art, with artists taking over exhibition spaces, cafes and bars, the Science Centre IMAX, and even the City Chambers. The festival website notes their commitment to “exploring visual music, sonic and digital arts.” Daemen notes that the audience reception of her “VR opera” has varied based on where it has played; at film festivals, audiences come with wildly different expectations and mindsets than at visual art installations, and Daemen reckons “Songs for a Passerby” has been the “weird one out” every time it has played, whether in a concert hall or a fine art gallery. “Songs for a Passerby” does not have the plot I expect from a stage drama; maybe a plot would defeat the purpose. Evoking the out-of-fashion “city symphonies” of 1920s cinema, the work gives each audience member a chance to engage, observe, and reflect on their place in art and technology.

After four centuries, does opera need to embrace cutting-edge technologies to stay relevant? Can one even call VR “cutting-edge,” given its popularity (albeit a specialist one) in the video game industry, and that NASA was training scientists with it over 40 years ago? Moreover, VR is an intensely, innately solo experience, almost antithetical to the communal practice of theater-going—perhaps the greatest limiting factor for fans of live performance. But maybe this is an overly cynical approach to Daemen and the creative team’s work, who have thoughtfully synthesized the elements of each art and science in service to their message of thoughtful observation and engagement.

From the UK, it is difficult to see more experimental modes of operatic presentation such as “Songs for a Passerby” outside of the last few years of operatic discourse. Following the chief executive of Arts Council England’s much-mocked provocations for the future of the art form: Is VR the next step beyond pubs and parking lots? Opera funding in the UK has become intensely scrutinized and fractious over the past two years, with the most publicized of these issues stemming from the ACE cuts to many opera companies, most notably English National Opera and Welsh National Opera. As I write this, WNO’s Orchestra and Chorus have suspended their immediate planned strikes, having set action short of a strike for the opening night of “Rigoletto” on September 21 with the situation still developing. This follows a 35% reduction in funding received from ACE and a 11.8% reduction in funding received from the Welsh Government, leading the opera company’s management to propose pay and hour cuts during a nationwide cost of living crisis. As reported by VAN, the review into ACE’s methodology and decision-making closed swiftly and silently last week.

The Scottish arts scene is largely funded by different institutions, but Creative Scotland’s series of cuts, reversals, and reinstatements casts a similar shadow. Last year, the long-established Lammermuir Festival, a cornerstone of the Scottish classical music scene, lost its Creative Scotland funding after three rounds of applications and encouraging feedback at each stage; this blow came a mere 16 days before their 2023 edition was due to open. The environments for hosting—let alone creating—these experimentations with form are threatened on both sides of the border

It is hard to see VR opera taking the world by storm, but “Songs for a Passerby” utilizes its separate artistic elements to create a unified experience. Its lack of literal communality might not be what Richard Wagner had in mind when he spoke of his gesamtkunstwerk, but Daemen, Horwitz, Fels, and Hertier have created a piece that absorbs the senses and addresses interpersonal issues in content, if not in form. Perhaps “Songs for a Passerby” does not meaningfully expand the potential of opera, but it remains a captivating, comprehensive exploration into what a total work of art can be, with an admirable clarity of purpose. ¶

“Songs for a Passerby” can be heard at Sonica Glasgow until September 29.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.