In September, the legendary German filmmaker, author, actor, opera director, and skateboarding-opinion-haver Werner Herzog turns 80. Herzog’s use of music in his films is noticeably more eclectic and more surprising than that of most of his director colleagues, according to our contributor Thomas von Steinaecker, who is currently finishing a documentary on the artist.

A rocky cliff. On the left, the outcroppings are covered by dark vegetation; on the right, the stone disappears into a light screen of fog. We look closer and realize something is moving. A group of people, traveling single-file, snake downward, as tiny as ants. They are at the boundary between the cliff and the fog. Slowly, we realize who these people—marching between heaven and earth, between life and death—are: an army of Spanish conquistadores. Their proud uniforms are clumsy in this environment. Their bulky outfits stand in stark contrast to their aim, of conquering the mountain.

This is the opening shot of Werner Herzog’s 1972 film “Aguirre, the Wrath of God.” The shot has become iconic. But the abstract beauty of the image only partially explains its reputation.

There’s something else there, something that you also perceive gradually. It’s not seen, but rather felt and then heard. Maybe it can be explained by a paradox: The cinematography recalls a documentary, but we are watching events that happened in the 16th century, and hearing futuristic electronic sounds that evoke a choir of angels. Image and music contradict each other. Through this contradiction, they create an atmosphere which terms like “celestial” and “spherical” come closest to describing.

The French electronic music pioneer Jean-Michel Jarre has correctly pointed out the cutting-edge nature of the “Aguirre” score. While ‘70s-era science-fiction films like “Star Wars”—films which you might expect to have innovative soundtracks—hew closer to the musical vocabulary of the 19th century, Herzog’s low-budget historical “Aguirre” was one of the first movies to use an electronic score, influencing a generation of film composers in the process.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

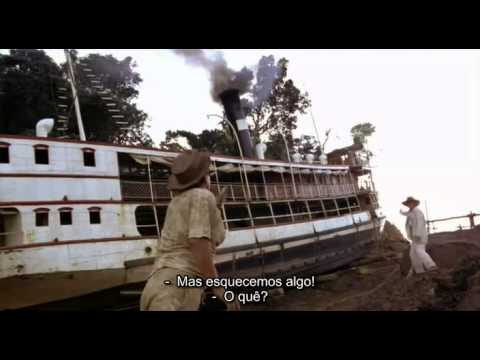

Herzog doesn’t read music. The CD collection in his little studio in Los Angeles is limited and consists mainly of operas. While writing, he sometimes puts on Beethoven’s piano concertos. He almost never goes to concerts or live opera. Still, Herzog’s relationship with music is both highly unusual and unusually diverse. The evidence for this may be found in his over 60 films, most famously “Fitzcarraldo,” about the eponymous music fanatic who is so obsessed with the idea of having Enrico Caruso perform in the Peruvian jungle that he tries to build the tenor an opera house there, dragging a multi-ton Amazon steamship over a mountain in the process.

Herzog is also more than a filmmaker. He considers his work as an author at least equally important. Besides that, he’s staged over 30 operas at houses around the world, including in the U.S., where he’s lived for the past three decades. He’s become a popular interview partner, frequently discussing the nature of music. A charismatic old warrior with a soft, raspy voice, he comes across like a film-world Obi-Wan Kenobi. (It’s no coincidence that Herzog has become a cult figure for younger audiences through his role in the “Star Wars” spinoff “The Mandalorian.”)

The band Popol Vuh, headed by Florian Fricke, composed the soundtracks for Herzog’s most famous movies of the ‘70s and early ‘80s. (Punning on his 1999 film “My Best Fiend,” about his fraught collaboration with actor Klaus Kinski, Herzog once called Fricke more simply “my best friend.”) Fricke lived between 1944 and 2001 and engaged a rotating crew of guest performers for his scores. He was also a classically-trained musician and, in the late 1960s, was one of the first people in Germany to get his hands on the then cutting-edge synthesizer, the Moog III (he later sold it to the band Tangerine Dream).

Since Popol Vuh was active in the same time and place as krautrock bands like Cand and Kraftwerk, its music is often grouped in with these groups, which developed a unique, electronics-influence style of German rock music. But Fricke’s music resists categorization, especially since he avoids traditional rock-band instrumentations and obligatory elements like percussion beats. The magical opening of “Aguirre” was performed on a so-called choir organ, a unique (and now lost) version of the Mellotron that electronically distorted samples from choir voices. Later in the film, Fricke creates a difficult-to-place, melancholy sound—an electric guitar threaded in with a volume pedal. The creepy homophonic opening choir of “Nosferatu” (1979) could be mistaken for a piece by Henryk Górecki, while “Fitzcarraldo” hums and strums in celebration of a simple C major chord.

Still, it would be incorrect to call Fricke Herzog’s house composer, as John Williams was for Steven Spielberg. Fricke’s ten soundtracks for Herzog form just one facet of Herzog’s varied and often cutting-edge use of music. Herzog’s musical selections have always been more eclectic and more surprising than most of his director colleagues. (The best comparison is maybe Stanley Kubrick, who had his spaceship float through the galaxy to the sounds of Strauss’s “Blue Danube” waltz.) In Herzog’s early, apocalyptic film-essay “Fata Morgana” from 1971, he combines shots of the desert with the Kyrie from Mozart’s “Coronation Mass” and songs by Leonard Cohen. In the tragicomic ballad “Stroszek,” from 1977, Herzog juxtaposes Beethoven and country music. Since Herzog moved to California in 1995, he has turned increasingly to documentaries. In this genre, he doesn’t restrict himself to a single style of music either. He’s collaborated most with the Dutch jazz cellist Ernst Reijseger, who contributed soundtracks to films like 2010’s “Cave of Forgotten Dreams.” Herzog has also worked on individual projects with the folk-rock musician Richard Thompson (2005’s “Grizzly Man”) and the slide guitarist David Lindley (2009’s “Encounters at the End of the World”). In his feature films, Herzog has even begun using more traditional Hollywood scores, working with composer Klaus Badelt.

Counterintuitively, these more traditional scores demonstrate what makes Herzog’s use of music so special. The soundtracks for 2006’s “Rescue Dawn” and 2015’s “Queen of the Desert” follow the conventions of film scores: The music underscores the emotions of the protagonists. But in Herzog’s German feature films and in most of his documentaries, people are not the protagonists—landscapes are. Put another way, Herzog sees people as just one element of the many that make up a world. These extreme external landscapes become internal states; the camera shows the characters not as psychologically differentiated individuals, but as archetypes. Herzog says that music lets an “inner truth” emerge, something you could also term an “atmosphere” or “space.” The two-dimensional image gains depth. It becomes a metaphysical relief.

In Herzog’s most recent documentary, “Encounters at the End of the World,” the camera follows a penguin that has lost its mind. Instead of seeking out the ocean, like the others, it starts waddling toward the middle of Antarctica. “With 5,000 kilometers ahead of him, he’s heading toward certain death,” Herzog notes dryly in his narration, in his inimitable Bavarian accent, thick with destiny and—depending on the mood—either brutality or irony. Underneath the action we hear Russian Orthodox church music sung by a male choir a cappella. This music has been part of Herzog’s repertoire since the ‘90s. These sounds, which are sustained for long periods before trailing off, evoke the vastness of the space the penguin seems willing to traverse. Even if you don’t immediately grasp the relationship, the sounds give the scene a sacred, mythical and mystical quality.

Of course, a discussion of music in Herzog’s films would be incomplete without mentioning Richard Wagner. At first glance, it seems that Wagner’s romantic pathos, his intention of overwhelming the senses, and self-identification as an uncompromising, misunderstood genius, would make him fit naturally with Herzog’s aesthetic preoccupations. Herzog has used Wagner’s music often, perhaps most impressively in the 1992 Gulf War documentary “Lessons of Darkness,” which turns the war into a cosmic (natural) catastrophe. The “Funeral March” from “Götterdämmerung” sounds as the camera flies over burning oil fields (without narration). That juxtaposition led to criticism of Herzog at the time; he was accused of aestheticizing brutality. But critics overlook the fact that despite Herzog’s undisguised pathos, he is always telling stories of failure—most famously that of Fitzcarraldo, who despite his superhuman striving never manages to build his opera house on the Amazon and who must content himself with an improvised, ridiculous performance of Verdi’s “Ernani” on his run-down steamship.

Herzog has emphasized the overlap between his films and the artform of opera. “It doesn’t matter that so many of the stories are implausible,” he says. “When the music is playing, no explanations are required; primordial feelings suddenly reverberate within us. Strong inner truths shine through, and the veracity of facts no longer matters.” It’s an observation that holds true for many of his films, too.

With that in mind, it’s not surprising that Herzog directed his first opera three years after the spectacular “Fitzcarraldo,” namely Ferruccio Busoni’s “Doktor Faust” (probably not a coincidence). In 1987, Herzog directed “Lohengrin” in Bayreuth. It was Wolfgang Wagner’s idea. Herzog declined at first, but Wagner sent him a cassette of the overture to “Lohengrin”; Herzog was driving when he heard the work for the first time and was so overwhelmed that he pulled into the breakdown lane to listen. Herzog told Wagner he would do it. It’s true that much of the still-fascinating concept of Herzog’s Bayreuth “Lohengrin” goes back to the director’s longtime set designer, Henning von Gierke. Von Gierke created a seasonal cycle to accompany the three acts of the opera, including a frozen pond for winter.

But Herzog’s original plan for the staging illuminates the roots of his personal fascination with opera. He wanted to drag cliffs from the Bavarian Forest to Bayreuth and then set them up in a half-circle around the Festival Hall. “Sadly, that was forbidden,” von Gierke recalls, “because Wolfgang Wagner said, ‘We do indoor theater, not outdoor theater.’” (Von Gierke suggested creating cliffs out of paper maché, which Herzog vehemently rejected.) Filming “Fitzcarraldo,” Herzog melded almost indistinguishably with his protagonist when he insisted on filming an actual ship being pulled over the mountain, rather than a prop; in that film, as in his staging of “Lohengrin,” the process becomes a kind of ritual act, the ritual in turn infusing reality with mystery. As Herzog likes to say, a metaphor is created, though it is never clear what exactly this metaphor represents.

Herzog’s 30 opera stagings are little more than a brief episode in his life. He doesn’t plan to create further work in the form, preferring to concentrate fully on his films and his writing. As a better composer counterpart to the artist than Wagner, I’d suggest Gesualdo. The aristocratic Italian, a driven genius and an abject failure, is an archetypical Herzog character. Catching his wife in flagranti with her lover, Gesualdo brutally murdered her. As penance, he had his servants whip him daily, and tried to single-handedly clear an entire valley of its vegetation. He became extremely depressed and died alone.

Herzog shows Gesualdo’s destiny in one of his most beautiful and least known documentaries, “Gesualdo – Death for Five Voices,” from 1995. Gesualdo’s Sixth Book of Madrigals, one of Herzog’s favorite pieces of music, sounds at once modern and archaic, its harmonies out of time and not of this world. As Herzog says, the music is like “a foreign planet in our galaxy.” It’s a description that fits Herzog’s best films as well. Maybe one day we’ll still experience his ultimate staging, a project he still refers to from time to time. In the early 1990s, he planned to put on Wagner’s “Götterdämmerung” in a small Sicilian village in the ruins of an opera house, where construction began and was abandoned. Before the third act, the building will be blown up, and the rest of the opera will take place in the wreckage. ¶

Thomas von Steinaecker’s film “Werner Herzog — Radical Dreamer” premieres in October 2022.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.