On November 30, the opening night of the Metropolitan Opera’s revival of “Tannhäuser,” we had reached the engrossing song contest in the Wartburg Castle from Act II. Baritone Christian Gerhaher, making his house debut in the role of Wolfram, was singing “Blick’ ich umher,” the character’s song on courtly love. As the music and libretto dipped into the metaphor of love as a spring, a protestor from the climate activist group Extinction Rebellion NYC unrolled a banner from high in the Family Circle section, stage left, and began shouting “Wolfram, wake up, the spring is poison! This is a climate crisis! There will be no opera on a dead planet!” He was followed by another on the opposite balcony; after they were removed and the opera restarted, a third protester began shouting from the orchestra seats.

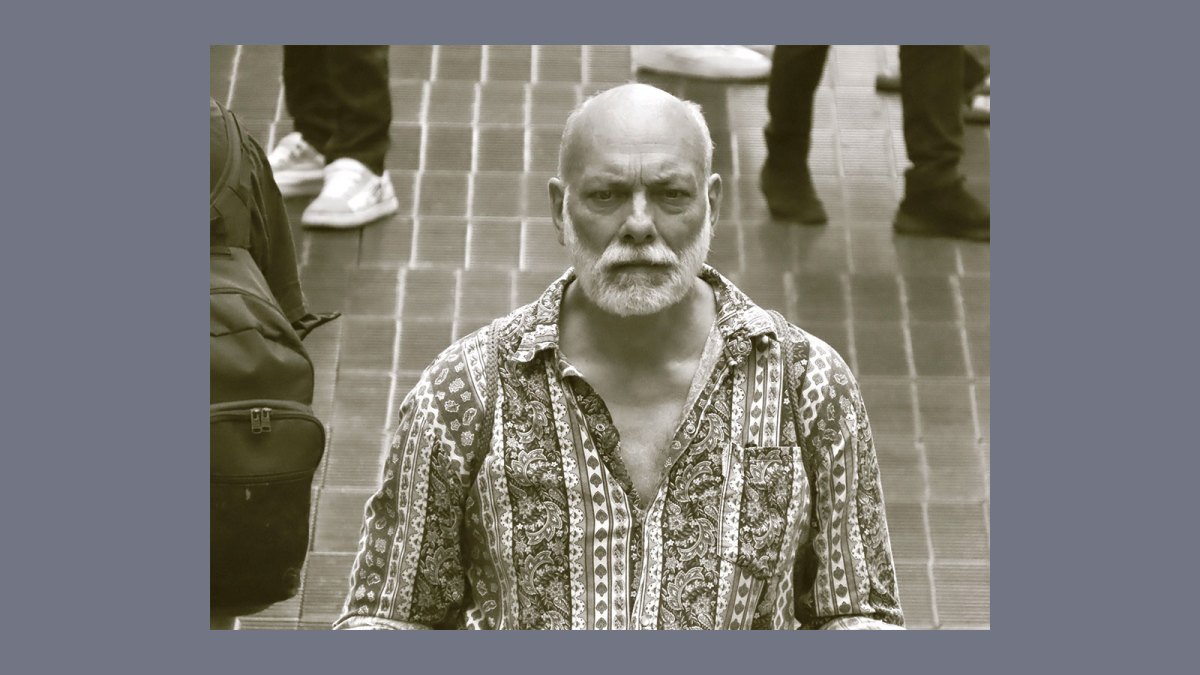

The first protester was John Mark Rozendaal, a cellist, gamba player, and teacher. He was the founding Artistic Director of the Chicago Baroque Ensemble, has served as principal cellist of The City Musick, and performed with many of the leading period instrument ensembles in the U.S. He is also a coordinator with Extinction Rebellion NYC. The weekend after the night at the opera, he spoke with VAN about the protest.

VAN: Why did you choose to protest at “Tannhäuser”? You mentioned in an email to me that it was process of elimination: you didn’t want to protest at “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X” or “Florencia en el Amazonas” because you saw those operas as having more diverse audiences. What determined that decision? Why didn’t you want to protest in front of those audiences?

John Mark Rozendaal: We say, “We disrupt what we love.” We’re encouraging people who have a commitment to climate justice to take it to their own communities. I’m a musician, so when we were talking about low numbers of participants in high impact actions, when we were talking about disrupting what we love, one of our friends said to me, “John Mark, what about the Metropolitan Opera?” I was terrified. I realized that I could not say no, after everything I’ve said and done in my life. I could not back off from that. So we had to do it.

But the African American community and the Latino community, those are places where I don’t have a voice. I shouldn’t have a voice. I have to support those communities by listening. But “Tannhäuser” is the blue-eyed Northern European thing. That’s obviously my people.

When I saw it was on the schedule, I remembered having watched the broadcast of it many years ago, and this enthralling scene in Act II. I was fascinated by how the music of the good guy, Wolfram, was so insipid, and how the music of the apostate, Tannhäuser, was so compelling.

I remembered the imagery about the spring, and an alternate story came to my mind. Making an alternate story is part of what this action was all about. The situation we are in in the world is that our leaders have conditioned us, they’ve programmed us, they’ve prepared us, they’ve rehearsed us to play out a drama that ends with mass extinction. Extinction Rebellion is saying, We’re not playing the parts that have been written for us, we’re changing up the script. Wagner’s voice is responding to Wolfram by saying, No, this spring is not made to be reserved and untouched; it needs to be enjoyed. And we changed it up so when Wolfram says the spring is magical, pure and untouchable, we said the water all over the Earth is polluted and poisoned. That’s the response we need to have to this, not the mythology about the purity of nature.

Within our organization, we’re urging each other to take this fight to our own communities. I’m a classical musician.

How do you see the audience in the action? Are they literally an audience for your performance?

That’s complicated. The comments under the New York Times review are really interesting. People are debating, “Are you going after the rich people who really have some power?” and “Don’t you understand that people struggled to put together that $25 to sit in the cheap seats?” We’re aware of that; we know that the Metropolitan Opera audience has that breadth inside it. [But] because of the way the Met has been marketing itself, many of the people you see at the opera are what we used to call yuppies, who go there as tourists and don’t really know opera, and it’s a social thing.

Where I was sitting in the orchestra section, there was a broad range of people. There were some there on $25 rush tickets; many committed, multinational fans of opera in general and “Tannhäuser” specifically; a dozen teenagers who seemed to be on a field trip with two adults. They were multiracial and from a broad range of socioeconomic backgrounds. You can’t know and see all 4,000 people there.

Sure. To be a little bit glib, our target audience is everybody, because everybody is affected by the climate crisis. We understand that people’s responses to a disruption like this will be on a spectrum. We’ve got people who are already with us; people who are strongly in sympathy with us; people who will jump on board and be with us next week. We’ve got people who already know a lot about the climate crisis and will be supportive. We’ve got people who know a lot about the climate crisis and who will distance themselves: That’s not the way to do it. We’ve got people who do not care. And we’ve got people who will be in opposition to what we did for all sorts of reasons. They are all our audience.

We would love to see the people who are teetering on the verge of being willing to take action themselves join us. We’re talking to them. We’re talking to people who have the wherewithal to push the donate button on our website. We already saw that in the comments on the New York Times article, people saying, “I’m going to donate now.” So that’s working for us.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Do you know how many people who are commenting were actually at the event?

It’s a good question. But even people who weren’t there have interesting opinions. There were people in the comments who said, “Yes, there are people in the Metropolitan Opera audience who are invested directly or indirectly in the fossil fuel industry.” That’s pretty obvious.

Actually, as security was holding us in the lobby, my friend Dancing Leaf, who was the second protestor over in the balcony—she’d never been to the Metropolitan Opera before. We’re standing by this column, and she sees engraved on it, “Texaco supports the Metropolitan Opera.” She didn’t know that Texaco had underwritten the broadcasts. That’s all much more sub rosa now, you don’t see [sponsor] names on any productions anymore. What you see as the sponsors of the productions are the Metropolitan Opera Guild [The program booklet for “Tannhäuser” credits a gift from The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation and the Metropolitan Opera Guild, with a gift from the Metropolitan Opera Club assisting the revival.]. You can barely find out who’s in the Metropolitan Opera Guild; you can barely find out where they got their money. If you did, you’d find out that it comes from arms dealers, and it comes from coal.

Even if we don’t change their minds at all, we want them to know that we see them, and what they’re doing is not OK. We’re not sure that we’re going to change any minds there, but it’s not OK: a few rich people acting in ways that will cause the deaths of millions of poor people and [us] not telling them what we think about that.

What about protesting at season opening nights or gala events attended by more public figures, wealthy people, celebrities? I understand you’re saying that your audience is everybody, but does it make a difference to influence people who have a broader public following or a public voice?

Extinction Rebellion NYC’s mission is to create a movement. We’re looking at what happened in the Netherlands over the last year, where they started out with 60 people sitting on the highway blocking it. And they kept on doing it every week, until they had tens of thousands of people sitting on the highway. And then they persuaded their cabinet to actually demand some accounting on the effects of the fossil fuel industry in their nation.

That’s what we want in the United States. We want Extinction Rebellion to be a household name, as much as it already is in the United Kingdom. I also am personally active with Climate Defiance, which makes much more of a practice of targeting public figures. It’s not an either/or, it’s a both/and strategy.

Where I was sitting, everyone took the protest in stride, but there were angry reactions around the hall that added to the disruption. What were the reactions like around you?

I actually misremembered the layout when I bought the tickets, because I thought the Family Circle was box seats. The nightmares I was having a week before it were that they’re just going to pull me out through the door. And then when I got up there, there’s an exit at the front and one at the back. I dropped the banner, started my little speech, and then I walked back so that I was halfway between the exits. It was dark there; they couldn’t see me. So that’s why it took them forever to get to me. It didn’t play out exactly the way we expected because they just couldn’t find me. I was shocked out of my mind; I just had to keep on yelling and yelling.

When I saw the curtain coming down, security hadn’t gotten near me. I was prepared to hit the floor and make them carry me out. But by the time the curtain had come down, there was no point in risking my safety with that kind of resistance. The house manager or whoever just walked up and said, “Let’s go.” And I went with him.

Linda down in the orchestra had to be protected by security. So there was actually no point in our resisting. But I think that’s why we weren’t arrested. When they asked us to leave, we left. The police came and asked what happened and the house said, “These people made some noise.” There is no trespassing charge.

That’s consistent with what has happened with our museum actions, where consistently, security is standing down. They won’t touch us before closing time. If we want to get arrested, we stay after closing time. They’re at the point where they’ll let us do leafleting, they’ll let us scream, shout and make speeches, as long as we’re not damaging stuff.

How did the opera patrons around you react? I saw a good number of people who left after the second intermission, because of the delay, talking about how they had to get the last train or express bus back home.

Where I was, those seats are mostly what they call the score reader seats. Those are inhabited by the hardcore, the geekiest people in the world, those aspiring to be opera directors and Wagnerites. One guy actually did ask me if I was being paid, and I forgot rule number one: You don’t engage with that. There were people clutching their pearls, so to speak, saying, “Oh my God, he’s rude.”

The day before was a very hard day. I was terrified. I was thinking, What am I terrified of? And I realized I just did not know what was going to happen. We didn’t know what the audience response was going to be. I knew there would be people whose first instinct would be to try to help the show go on. Their instinct would be to just stay quiet and wait for it. But in the last year, I’ve participated in as many direct actions as I possibly could. I’ve interrupted a tennis tournament in Washington D.C., and the New York Economic Club when Jerome Powell was there, and a Chuck Schumer fundraiser at the Harvard Club.

I’ve noticed that the people who feel the most privilege to be violent are actually wealthy people. People at the [Massachusetts Governor] Maura Healey fundraiser had to be physically restrained by their friends from accosting us. Likewise at the Harvard Club; they were remarkably physically aggressive there. As an old white man—in some contexts people are hands-off. But not at the Harvard Club. They did not care that they were shoving and dragging.

And speaking of disrupting, I’ve been a fan of Christian Gerhaher for years, and disrupting what you love means I interrupted the most beautiful thing of the whole opera. ¶

Correction, 12/15/2023: Paraphrasing a discussion in the comment section of the New York Times, Rozendaal’s quote originally read, “Yes, there are people in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra who are invested directly or indirectly in the fossil fuel industry.” He actually referred to the “Metropolitan Opera audience.” VAN regrets the error.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.