It’s at around the 15-minute mark that I’m pretty sure I’ve pissed off Renée Fleming. Speaking with America’s most famous living soprano just before last October’s release of her latest recording, “Voice of Nature: The Anthropocene,” I’ve gone into our conversation anxious to discuss one of the album’s central themes: the climate crisis.

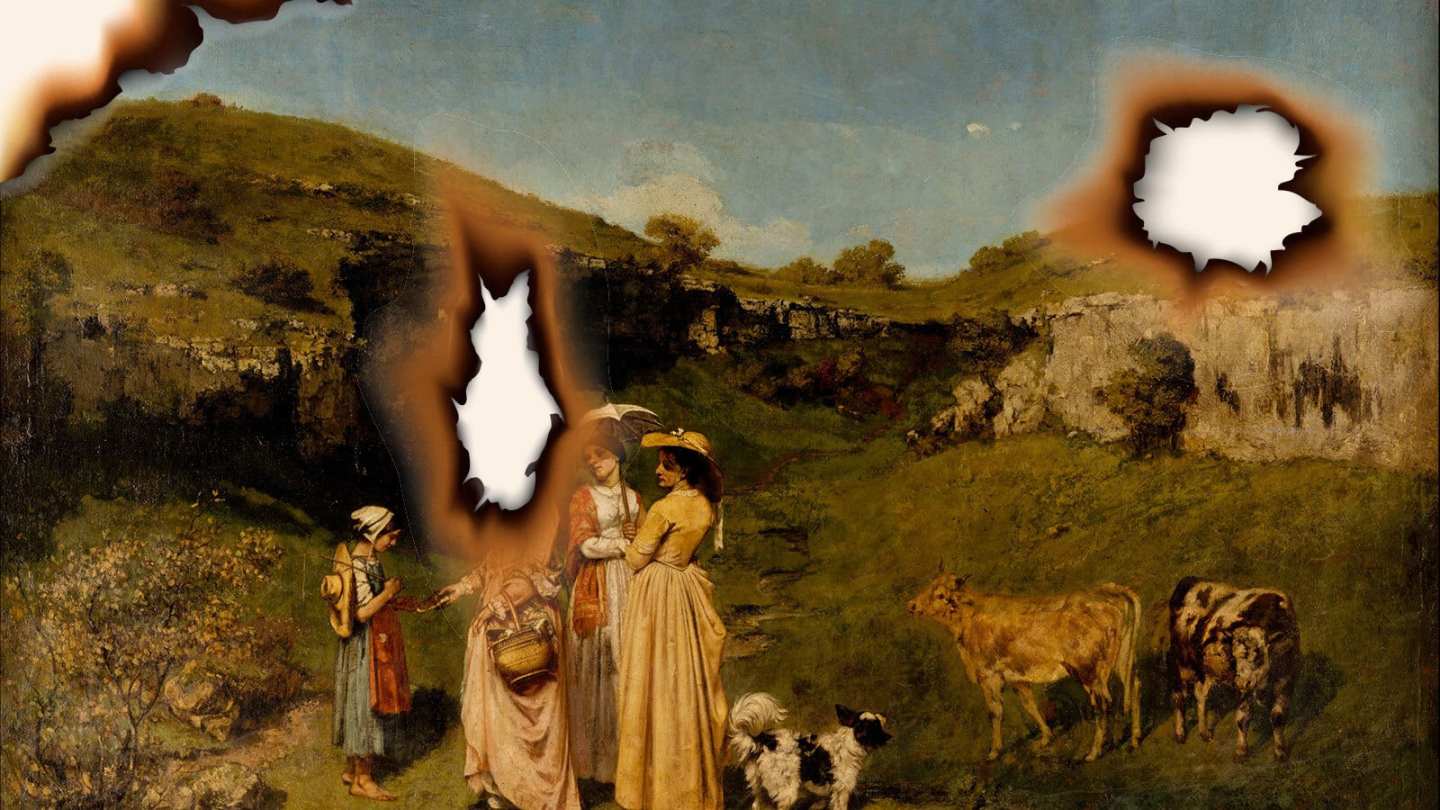

Programming for the album began in 2020, during the early days of lockdown. At the time, Fleming had recently relocated from her Upper West Side apartment to a five-bed, five-bath house in the DC-adjacent diplomatic hamlet of McLean, Virginia (other features include three stone fireplaces and a sculpture garden). She spent much of that forced downtime hiking in the woods surrounding the new property and thinking about a time, 200 years earlier, when poets and composers celebrated the romantic—at times holy—sagacity of nature. She began to think about those works in relation to the climate crisis.

“Climate change has just come out and smacked us all in the face,” Fleming tells me, before saying a line I’ll hear her repeat (almost verbatim) several times over in the subsequent media coverage for “Voice of Nature”: “Mother nature has said ‘Pay attention!’ in the last several months. So I’m paying attention.”

But Fleming prevaricates when I ask about whether she’s considered her own habits as a traveling musician. “It is challenging for us, because we can’t work if we’re not traveling. It’s the only way we can really practice our art form, unless we went back to a system where you were in an ensemble.” I brought up Malena Ernman, the Swedish soprano—who also happens to be Greta Thunberg’s mother—and her practice of only taking engagements she can travel to by train, ferry, or car. Perhaps not possible for getting from New York to Los Angeles, but what about, at least, the Northeast Corridor—the train line connecting Boston to Washington, DC?

“I haven’t considered it yet,” she answers. “As a singer, I don’t travel as much as instrumentalists, who can kind of perform every day.”

Fleming then pivots to policy change as what will really “move the needle on climate change,” and it’s here that I begin to hear an edge take shape in her voice. Having campaigned for Biden and being a member of his arts council, I wonder if that was something she herself could advocate for. “I don’t know,” she sighs after a slight preamble. “Truthfully, this is new for me. My real passion and how I spend my extra time outside of singing has been at the intersection of health, medicine, neuroscience, and the arts.” We’re both a little relieved when the conversation wraps up shortly thereafter.

In truth, I enjoyed “Voice of Nature” which, much like 2001’s “Night Songs” with Jean-Yves Thibaudet, showcases Fleming’s underrated talent as a recitalist. Curatorially, the new album is a vibrant bouquet of wildflowers from Grieg, Liszt, Fauré, and Hahn, interspersed with top-tier commissions from Kevin Puts and Nico Muhly and a new work by Caroline Shaw. Fleming has also had a history of speaking openly and frankly about the challenges of the classical music industry, especially from a gendered perspective. Her 2004 memoir, The Inner Voice, doesn’t lack for the fluff of celebrity memoir; it also presages today’s discourse around gender inequity and the anxiety attached to high achievement. While written nearly 20 years ago, lines like “as a woman in particular, I feel I wasn’t socialized for success” would feel right at home on a Twitter thread or in an episode of “Call Your Girlfriend.”

In some ways, Fleming has a point. While climate change is demonstrably man-made, this is largely through two influences—greenhouse gas emissions and activities that affect the reflectivity of the earth’s surface, like deforestation—that are beyond any one person’s control. Much of the messaging around personal climate responsibility has historically been corporate damage control. Keep America Beautiful, the nonprofit behind an iconic 1971 PSA of a Native American (actually an Italian-American actor, but that’s another story) shedding a single tear over highway litter, was funded by corporations including Anheuser-Busch, Procter & Gamble, PepsiCo, and plastics industry front group the Council for Solid Waste Solutions. More recently, the impetus for us fretting our individual carbon footprints is because of a British Petroleum campaign spearheaded by Ogilvy & Mather that mainstreamed the term. Forget about our oil spills. You’re using too many straws.

Fleming alludes to this in our interview. “A lot of governmental forces have tried to make us feel that we can make a difference [by changing] the things that we do, whether it’s plastic consumption or carbon footprint. But the truth is, the change really needs to occur at a much higher level when you have major corporations financially undermining and bribing in order to have these [environmental] policies not enacted.” She adds: “That’s the thing we really should be talking about: How do we make ourselves heard and make ourselves loud enough for politicians to understand that they really need to take action?”

At the heart of this is the disconnect between what we say and what we do. Fleming’s comment that, as a singer, she doesn’t travel as much as instrumental soloists came just a few minutes after mentioning that she had seen her “Voice of Nature” recital partner, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, open the Metropolitan Opera’s 2021-22 season on September 27 and Carnegie Hall’s season on October 6—commuting to Paris for concerts in between. When we spoke, she was in between multiple-country concert tours of Europe, which in this case also meant multiple transatlantic flights.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

It’s hard to separate artistic institutions from the profits of climate change. The Metropolitan Opera’s board drips with oil money, including a historical partnership with Texaco that lives on in former CEO and honorary chair James W. Kinnear. The late George Lindemann, who, along with his wife (and current Met Board President and CEO) Dr. Frayda B. Lindemann, is the namesake for the company’s young artist development program, was the chairman and CEO of Southern Union, and a general partner of Panhandle Eastern, both pipeline companies. At the time of the Keep America Beautiful ad, Joseph Neubauer (husband of board secretary Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer) was an executive at PepsiCo.

Of the 25 listed corporate supporters of Carnegie Hall, 12 are also represented by executive leaders on the Business Roundtable, a group that last year opposed a $3.5 trillion budget bill to address greenhouse gas emissions through taxes largely aimed at the wealthy (following research that has linked nearly half of the world’s CO2 emissions to the wealthiest 10 percent of the earth’s population). One of the Roundtable’s other members, Travelers Companies chairman and CEO Alan D. Schnitzer, is also the chair of the Corporate Fund for the Kennedy Center, where Fleming serves in a leadership role as an artistic advisor.

Around the world, many institutions are both acknowledging that systematic change is needed to avert the worst-case climate scenarios and looking for ways to change their own outmoded policies and practices. The annual Culture, Climate and Environmental Responsibility report, copublished by Arts Council England and the UK nonprofit Julie’s Bicycle, tracks CO2 emissions for 636 national arts organizations of all sizes year over year. Their latest report calculated nearly 84,000 tons of carbon emissions from these groups—the average UK household emits around 19 tons per year. While Arts Council chair Nicholas Serota agrees that action is needed from the for-profit sector, he adds that “artists and arts organizations can shape conversations about the environment. They can challenge and be provocative, both informing and opening our minds.”

The same is true for artists and organizations in the United States. The California-based Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music has an ambitious climate commitment, with a statement that serves as a counterpoint to the inevitability of an artist’s career that Fleming points to. Frank says, “The long-accepted lifestyle of the nomadic musician in pursuit of human connection and collaborative creativity comes at too high of a cost: Irreparable harm to the natural ecosystems of our planet, threatening human existence.”

In an article coauthored with violinist and founding member of the Fry Street Quartet Rebecca McFaul, Frank acknowledges that “individual actions won’t get us where we need to go without systemic change,” but adds that artistic commitments to climate action “pave the way by modeling the world we want to see and encouraging others to join the conversation. The same imagination we employ to reinterpret masterpieces and compose new ones can also be put to use to reinvent a profession we love.”

Individual actions, and individual actors as well: “The solution will not come from one musical group alone, as these orchestras and ensembles, even the most internationally-recognized ones, compete fiercely with each other,” composer Fabien Lévy wrote in VAN last September. “They risk high losses if they reduce their international travel or increase their travel costs and constraints. But there is an extreme urgency to act.”

The former and current directors of Sweden’s Helsingborg Symphony Orchestra and Concert Hall—Frederick Österling and Katrine Ganer Skaug, respectively—echo this sentiment. In 2019, the orchestra announced that it would work exclusively with artists who could reach the theater by car, ferry, or train—no flights. “From now on, we will only invite soloists and conductors who support us in the belief that classical orchestras can also play a role in moving towards greater sustainability,” Österling said in a press release.

In an interview with VAN’s German edition, Österling added that the ideal for this scenario would be a means of allowing many of Sweden’s 29 professional orchestras and ensembles “to share soloists and conductors on a national level.”

“There are orchestras and there are orchestras,” added Ganer Skaug. “We have our big Rolls Royces in the [Scandinavian] capitals. The rest of us…we have high artistic ambitions, but we’re primarily working for our local audience. Of course, we would love to have an article in The Strad, and we would love to have international attention for what we do artistically. But our main focus is to deliver high artistic quality to a local audience. In that respect, my neighbor orchestras are not my competitors—Netflix is my biggest competitor.”

Ultimately, both Österling and Ganer Skaug recognize that the policy change in Helsingborg is not, in and of itself, going to save the region from further carbon emissions. What’s important is that the change provoked discussion and debate, even within an area of Europe widely regarded as the greenest. “I was approached by so many colleagues asking, ‘So, what about this climate strategy? How are you doing it? Could we talk about it?’” Ganer Skaug recalls. “They all feel the pressure a bit because people would ask them that [after Helsingborg]: ‘So, what are you doing?’”

There is one key difference between these initiatives and Fleming’s “Voice of Nature.” Alan D. Schnitzer may not listen or pay attention to the Helsingborg Symphony, the Fry Street Quartet, or Gabriela Lena Frank. I’m willing to bet, however, that he does listen to Renée Fleming. Described in a recent New York Times profile as “the most famous American soprano since Beverly Sills,” Fleming’s stature within classical music in the U.S. is singular. Her track record as what Peter Gelb termed “the all-American diva” has seen her sing at a 9/11 memorial service, John McCain’s funeral, and the Super Bowl. For opera fans—especially funders—who may still question the facts behind climate change, even hearing one of their favorite artists acknowledge that it’s real could be significant.

“The difficulty with keeping climate change constantly present in mind is that it is massively depressing,” says Mark Bould, author of The Anthropocene Unconscious: Climate Catastrophe Culture. “E. Ann Kaplan talks about thinking about it in terms of pre-traumatic stress disorder on an individual as well as cultural level. Keeping it alive as part of the everyday is important. But I also hope that would give us the space to articulate it in a variety of ways.”

“In this conversation, her audience matters. How she uses her voice within that audience matters,” says community organizer and climate justice activist Meera Ghani. “If, through her exploration of the climate crisis, they’re moved by that exploration, that’s amazing.” Writing for the New Yorker, Oussama Zahr echoed this sentiment, praising Fleming’s curation for deciding to “communicate awe more than admonishment.”

In The Anthropocene Unconscious, Bould offers readings on everything from Karl Ove Knausgaard to The Fast and the Furious franchise that reveal the different ways that climate can be mapped onto the stories we tell in the 21st century. In a way, this is also what “Voice of Nature” does. In Fleming’s program, Romantic lieder written in a time before we worried over carbon emissions and single-use plastics take on a new layer of meaning. The disconnect between then and now becomes a connective thread. It’s this, Bould argues, that could be a useful tool in “bridging the gulf between, on the one hand, the too-little/too-late/if-at-all responses to climate catastrophe our political and economic systems are capable of producing and prepared to sanction, and on the other, a flourishing biosphere in which we too flourish.” It’s also, he adds, “essential to any long game seriously committed to life and diversity, equality and justice.”

This, too, is important: In films like the recent apocalyptic lollapalooza Don’t Look Up, the climate crisis is painted as an apocalypse soon that will destroy everything uniformly (at least for the 99 percent of humans who aren’t able to colonize a new planet). For millions, however—especially in the Global South, where the effects of Western energy and fuel consumption are being disproportionately felt in droughts, floods, famines, and climate-influenced conflict—that reality is now. It’s impervious to the punditry of statistics and solutions built around ifs, whens, and heavily-politicized either-ors.

“There’s no in-between,” Ghani says. “Maybe she’s creating the in-between.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.