- Third Coast Percussion: “Between Breaths” (Cedille)

- Wild Up: “Julius Eastman, Vol. 3: If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich?” (New Amsterdam)

- Kirill Gerstein, Berlin Philharmonic, Kirill Petrenko: “Rachmaninoff 150” (Berliner Philharmoniker)

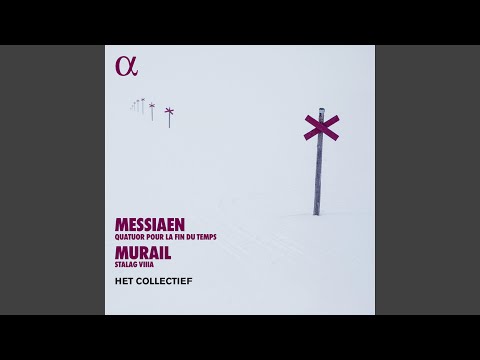

- Het Collectief: Messiaen: “Quatuor pour la fin du temps” (Alpha)

- Haymarket Opera Company, Craig Trompeter, Nicole Cabell: “Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: L’amant anonyme” (Cedille)

Are we still meant to be listening to music? This is something I’ve been struggling with over the last two-and-a-half months, even when I am, by virtue of my profession, actually meant to be listening to music. Either the political ramifications of a work start to become too foregrounded (try listening to Maria Callas in Cherubini’s “Medea” in this climate) or the chasm between what’s being played and what’s playing out in the real world feels too vast to bridge (which was, ironically, my experience of Peter Sellars’s refugee-“inspired” staging of Charpentier’s “Medée” at the Berlin Staatsoper).

In New York for a reporting trip last week, I had the opportunity to ask about a dozen musicians living and working in the United States whether they thought that music still had a place in such a divided and divisive atmosphere. Without fail, each one said “yes.” Even if it was a qualified “yes,” I was taken aback by the stark optimism of the answer. To be honest, especially as both a Jew and an Arab-American living in Berlin these last few months, I’m not sure anymore. Though perhaps that’s the lingering aftertaste of Igor Levit’s hastily-recorded, opportunistically-timely new recording of Mendelssohn’s “Songs without Words,” released in response to the attacks of October 7 with a seemingly blithe disinterest in the layers of context such a project could entail. Perhaps this shouldn’t be our reply to violence.

I don’t know if the following albums answer any of my questions. But here are five recordings that I didn’t get to include in VAN this year (until now), plus five highlights from this year of Stuff I’ve Been Hearing.

“Between Breaths”

In Anne Washburn’s prophetic 2012 play, “Mr. Burns,” a group of post-nuclear-meltdown, post-pandemic survivors are gathered around a fire. Surrounded by the detritus of civilization following its recent collapse, they struggle to remember the plot to an episode of “The Simpsons.” (The episode in question is the Gilbert-and-Sullivan–tinged “Cape Feare.”) Adding insult to irony, Washburn first workshopped the piece in a rehearsal space that was actually a bank vault underneath Wall Street. This cultural touchstone becomes a new lingua franca among the survivors, who turn Sideshow Bob’s attempts to murder Bart Simpson into a work of Homeric or Greek tragic proportions that survives through generations of the post-apocalyptic landscape. Like the ancient Greeks, they have found a way of injecting meaning into their meaningless world.

Missy Mazzoli’s “Millennium Canticles” takes its inspiration from “Mr. Burns,” refashioning the trajectory from ritualized storytelling into dramatic catharsis for the tireless quartet of Third Coast Percussion. A gasping pair of opening movements gives way to a more fluid form of storytelling that reaches full-throated redemption in the penultimate movement, “Choir of the Holy Locusts.” A final movement, “Survival Psalm,” is a more assured beginning to the cycle of storytelling.

“Millennium Canticles” is one of five new works on this high-octane recording from Third Coast, and while it’s the most substantive work, the other works—especially Tyondai Braxton’s “Sunny X” and Gemma Peacocke’s “Death Wish” are far from slouches.

Asmik Grigorian, Matthias Goerne, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Mikko Franck: “Shostakovich: Symphony No. 14” (Alpha)

Conductor Mikko Franck doesn’t need to do too much in terms of reimagination or gimmicks for this work; the challenge is to make each of these pieces fit together into a full narrative—to make sense of history as it plays out in real time. He achieves this, with Goerne and soprano Asmik Grigorian offering little comfort, but plenty of urgency. The first of a trio of Shostakovich recordings for baritone and orchestra that Franck and the Orchestre Philharmonique will release, this particular recording couldn’t be more well-timed. Read the full review from November 8.

“If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich?”

“If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich?” opens in a similarly ritualistic fashion to “Millennium Canticles,” with the choral members of Wild Up giving a discordant, disheveled warm-up scale to minimal instrumental underscoring. The vertiginous top notes are taken over by a trumpet that pauses at the apex of the scale before, like a roller coaster, the musical lines plunge down again. The real denouement comes about halfway through, when all of the low brass and woodwinds duke it out in the underbelly of sound, accented by the occasional chime.

Writing of Julius Eastman’s 1978 work on its 40th anniversary, the Cameroonian curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung notes the work’s central “tension between the cognitive, intellectual, and the economic,” which is an image that takes on a life of its own in Wild Up’s ecstatic (in the religious sense of the word) recording. Where does that tension break? Obviously in the underbelly. Where are its edges blurred? Maybe it’s in the moment where an oboe, operating at the top of its register, begins to become indistinguishable from a soprano’s voice.

This latest installment of Wild Up’s multi-part survey of Eastman’s works (under the fearless direction of Christopher Rountree) is bookended by “If You’re So Smart” on one side, and the composer’s “Evil Nigger” on the other. The latter work lives in the middle range, between the stratospheric highs and guttural lows of “If You’re So Smart,” and palpitates with multiple pianos, one sounding jittery and twangy, another more assured yet urgent, cosseted by low strings. In his 2018 essay, Ndikung traces the line connecting these two works, noting that Eastman’s deliberate use of the n-word forced audiences to confront their discomfort with race, while adding that the epithet was also central to the composer’s views on economics and class. Eastman himself drew this comparison in a 1980 statement given either to the Daily Northwestern or the Evanston Review: “You can’t wear Gucci shoes and be a nigger.” Perhaps all of this discomfort is what’s actually needed in 2023; either way, I didn’t realize I had begun to cry during this piece until it had finished.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Keith Jarrett: “Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach” (ECM)

Jarrett was 49 when he recorded these sonatas—younger than Carl Philipp (who was in his 30s when he wrote them). Jarrett is now older than the 60-something Johann Sebastian Bach in Griffiths’s narrative. Listening to his performance now, for all its understated brilliance of technique and cadmium-hued tones, I wonder where he was when he recorded it. Did he pretend to be Bach the elder, or Bach the younger? It’s a question that hangs over the entirety of the album for me, and while it’s not the one that Jarrett sought to ask in 1994, it becomes indelibly part of the listening experience in 2023. Read the full review from July 13.

“Rachmaninoff 150”

What would 2023 have been without at least a few standout albums among the dozens released to capitalize on Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversary? Kirill Gerstein doesn’t settle for virtuosic showmanship in the composer’s Second Piano Concerto, even in the work’s fiery opening. The work becomes a dialogue between piano and orchestra, at times an almost easy conversational volley between Gerstein and conductor Kirill Petrenko (who injects a crispness into the work’s lush second movement).

The performances, as well as balance between orchestral works and selections from solo piano works like the melancholic “Old Viennese Dances” and tentative “Morceaux de fantaisie” capture at once the high-voltage emotions in which Rachmaninoff so nimbly dealt. They also display a hesitance that seems right for a composer whose sesquicentennial was much touted as a cultural coup by Russian officials—despite his own ambivalent relationship with his home country.

Joel Frederiksen, Emma-Lisa Roux, Hille Perl, Domen Marincic: “A Day with Suzanne: A Tribute to Leonard Cohen” (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi)

It doesn’t lead to a straightforward poetic interpretation. Perhaps the objectification of Susannah in the Biblical story is balanced out by the autonomy and control of Cohen’s Suzanne. Perhaps they are the same person. Perhaps not much at all has changed between Susannah’s story and the commodification of women like Verdal and Ihlen as the muses of Great Men. Cohen was never one to shy away from fuzzy truths or hazy meanings. Nor does Frederiksen offer answers to these comparisons. They’re departure points for philosophical cruises through the sacred and profane, running the gamut from “Suzanne” to the title track of the last album released in Cohen’s lifetime, “You Want It Darker,” and drawing on just as many of Cohen’s thematic touchpoints: love, sex, religion, and death. It’s intellectual catnip, but it’s also a simple pleasure to hear these arrangements performed. Read the full review from February 2.

“Quatuor pour la fin du temps”

If “Quartet for the End of Time” didn’t pop into your head at least once this year, please let me know what your psychiatrist has you on because clearly it’s working. As musicologist Jan Christiaens describes the January 1941 premiere of the piece, “In the depths of the harsh winter of war, amid a diabolical regime of evil, incarceration, and deprivation, Messiaen gave voice to an angel, who promised no less than paradise and the end of Time.” The Belgian-born quartet Het Collectief’s recording renders the composer’s work at once as monumental and miniscule; reading at once the breadth of the end times as prophesied in the Book of Revelation and the intimate, miniature detail that Messiaen introduces into the composition. In their unsentimental, liminal reading, you hear the deprivation, and the double-edged promise of the end of time.

The draw of this particular recording is a new-ish companion piece, Tristan Murail’s “Stalag VIIIa.” Named for the camp in which Messiaen was interned, the work serves as a prelude of sorts to the “Quartet for the End of Time,” capturing in infinitesimal detail the cold—the unbearable, unendurable, glacial cold—of Görlitz in winter. Movement, gesture, and hope freeze over. Sound is reduced to the steely glint of light on icicles. If you can survive this baptism by polar vortex, you’re ready for the end of the world.

Awadagin Pratt, Roomful of Teeth, A Far Cry: “STILLPOINT” (New Amsterdam)

As rich as “STILLPOINT” is with T. S. Eliotisms as well as the nuances and idiosyncrasies of the album’s six composers, it’s Pratt’s performance that elevates each of these pieces to a realm of obsessive re-listening. Playing with a naturalism that at times leaves the piano lines sounding spontaneous, inevitable responses in a musical conversation, we hear both the life in Eliot’s thoughts and in Pratt’s artistry. He softly treads through the contemplations of Vasks’s piano solo, “Castillo Interior,” as if not to spook the thoughts that have settled. At times the piano springs to life with illumination, contemplation leading to epiphany. Briefly, Pratt lights upon the still point of the turning world, and brings us in for a closer look. Read the full review from August 31.

“L’amant anonyme”

Apparently there was also some happy music recorded in 2023. And I can’t think of much more to be happy about than finally having a full recording of the only surviving opera by Joseph Bologne, whose arias are a perennial delight on concert programs. The story of a young and wealthy widow and her lovestruck-yet-lower-class friend who plays a Cyrano-ish game of secret admirer to win her heart is simple and elegant, with a score that calls to mind moments from “Così fan tutte” and “Orphée et Eurydice” (had either Mozart or Gluck stuck around in Paris a bit longer). While not the most even recording, soprano Nicole Cabell blazes as the widow Léontine, especially in her velvety Act II aria, “Du tendre amour.”

Cyrille Dubois, Orchestre National de Lille, Pierre Dumoussaud: “So Romantique!” (Alpha)

Okay, fine, you get two happy recordings this year. Merry whatever.

There are tenors who fuck, and then there are tenors who fuck. Sure, hearing Jonas Kaufmann pump out “Winterstürme” is good for some heady thrills, and I wouldn’t not tuck Jussi Björling’s “Ch’ella mi creda” in my hope chest. But let’s talk for a moment about the ténor de grâce. At first blush, they may seem too lightweight to be seaworthy, carrying none of the Alpine heft of a Wagnerian or the velvet lining of a lyric—tenors who, if we were casting for a Hollywood film, would be played by one of the Chrises (Hemsworth, Pine, Evans… take your pick). The ténor de grâce would be a supporting character, played by Stanley Tucci. But let me tell you something about Stanley Tucci: That guy fucks. Read the full review from June 22. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.