Juliet Fraser is on sabbatical. “Actually,” she corrects me, “it’s a semi-sabbatical”—she’s still performing, but only sparingly. Mostly, she’s taking some long-overdue time to breathe, and to devote more attention to her other spinning plates. (She keeps several in the air, no matter the season.)

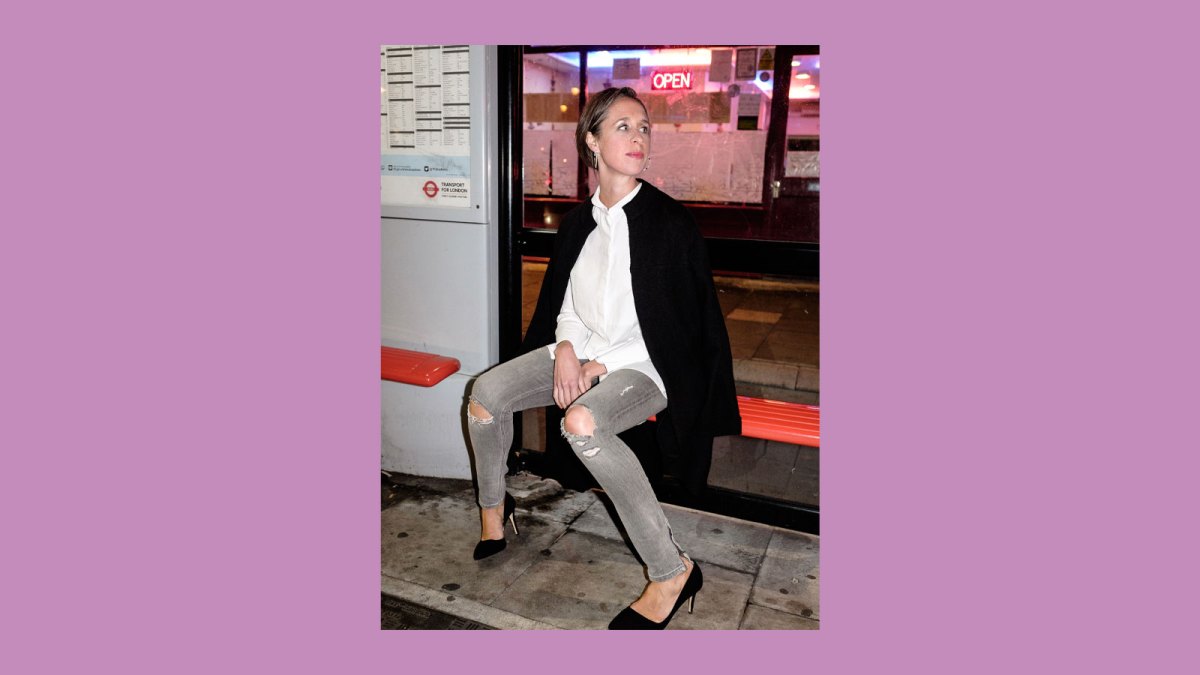

When I call her early on a Friday morning, she answers from the rustic warmth of a small Suffolk retreat she built two years ago and where she’s spending most of her fall. We talk for an hour or so and then pause to take a coffee break. When she returns to the screen, Juliet is much closer to the camera, having relocated with her laptop to the copper-colored kitchen. Newly drenched in the sun that pours generously through the floor-to-ceiling windows each morning, her trademark stripes of silver hair cleave her head in lines of electric white and gold.

Her video clicks back on just as she is midway through a long sip from a coffee mug that covers most of her face; when it lowers, I’m caught off-guard to find her brimming with an earnest and tender concern.

“When I was making coffee,” she says, “I found myself thinking, This is fun, getting to talk about myself. It’s really the first time that I’ve ever done something like it. But then I thought, OK, but what am I actually doing with it? What’s the point of this? What’s the point of a feature on me? At the moment, I’m thinking a lot about how to change the conversations in our field. So I’d actually like to ask you this time: What’s the point of doing a feature on me? Why are you doing this?”

I fumble for an answer. It seems so obvious. Juliet Fraser is one of those singular voices of a generation, a soprano who makes no apologies for the unaffected candor of her sound. It is an incredibly agile instrument, capable of spindle-thin tightropes and gossamer clarity—her work with Rebecca Saunders, including the behemoth “Yes,” puts this on full display—but in soft, secluded contexts it possesses a devastating and enveloping warmth that never hides its rough-hewn authenticity. Fraser was an oboist before falling sidelong and without training into singing. As a result, her sound makes no pretensions at the veneer of a classical technique. It bathes instead in a tumble-dried lightness whose nearest cousin is laughter, rounding off the corners of even the most treacherous phrase with a gentle, loving grain. It sits deep within the body, pure and unvarnished, sympathetic and grounded. Her uninhibited humanity has lent itself with extraordinary force to Cassandra Miller’s vulnerable and understated music—Black Truffle Records just released “Thanksong” on vinyl last month for this very reason—but it serves Morton Feldman just as well. Fraser’s recording of “Three Voices” is, perhaps, as close as that piece has come to perfect.

But I don’t tell her this, which I suppose she already knows and finds quite one-dimensional. Instead, I remind her of her other voice, the one that gets much less press but is, arguably, more virtuosic. In a field frequently all too happy to close itself off from the world, Fraser has spent a career straddling activism and art with a boundless and irreverent energy. She is an incisive critic of the status quo, dusting out the darkest corners of this niche art and insisting we tangibly rethink how new music negotiates the ethics of its economy, education, and labor. This work has often come at some personal cost (“sometimes you just have to get shit done,” as she says). In 2019, Fraser pledged to reduce her carbon emissions—substantial, for a freelance artist who travels internationally for most all of her jobs—by half (the proportion has increased considerably since). It has necessitated turning down gigs, or else vastly expanding her travel time to accommodate boats and trains instead of flights, frequently with inconvenient results: In March, she took a 36-hour boat ride from Lübeck, Germany to Helsinki, rather than the two-hour flight. But for all the difficulties, she says she doesn’t mind. The compromise brings other comforts and is worth the commitment to real change.

Despite her public life as one of the most sought-after interpreters of new music, what makes Fraser exceptional is her refusal to be just a contented singer. She curates an annual festival in London, eavesdropping, that spotlights experimental research and artistic practices entangled with intersectional feminism. Her Substack—a new venture in writing—is peppered with challenges to new music norms (her most recent post is an incisive critique of the “muse-myth,” reframing the gender roles of composer-performer work in fresh terms); her youngest endeavor, VOICEBOX, is what Fraser calls a “bespoke curriculum” for emergent singers to pursue specialist training in contemporary voice without having to bend to the pressures of a classical conservatory program. She is at all times imagining something better for this field and the people in it.

How do you convince a person who has spent her life deflecting from her own ego in favor of the bigger picture that she is just as important as her work?

I try anyway.

When my rambling praise stumbles to an inelegant close, Juliet casts a long, hard look above her screen with a silence just heavy enough to make me nervous. The first time we met, I quickly learned she has no qualms about cutting to the quick—it is what makes her such an effective activist—and it unnerves me to think she’s found a flaw in my reasoning. But the moment passes, her shoulders relax, and when she smiles, it is gentle and relieved, spilling in a way that lets you know she means it.

“I like that. Maybe I’ve banged on too much about changing things, but more and more, I’m understanding that it’s kind of who I am,” she says. “I mean…I’m really wrestling at the moment with how to use the voice I have. There is a lot that needs change. Some of it is very much in the current conversation—we’re quite focused on [equity, diversity, and inclusion] work, which gives me hope. But the conversation around environmental sustainability? The conversation around financial sustainability, around the precariousness of the freelance life? We’re just not getting very far with that. We’re babies in the classical music sector, with a dummy in our mouth and our ears blocked just waiting to grow up to enter the conversation. I feel quite frustrated by it.”

I pester: “Where does that leave your performance career?”

At this, Juliet laughs for a long time. She grins at me, shaking her hair back and throwing all the sun the southeast of England has to offer into a shimmer as she does. Still grinning, she quips, confident and self-assured: “I don’t know.”

The way she tells it, Fraser was 20 when she had her first crisis. Considering her long-held plan to pursue studies as an oboist after an academic undergraduate degree, she found herself at an impasse. “It was a classic early 20s,” she says with a smile, “suddenly confronting big questions and dealing with the shapes of your childhood and all of that stuff.” So she staged a private experiment: she gave up the oboe for a summer, leaving herself a wide enough margin on the backend to get her technique back in shape for graduate auditions in case she missed playing.

“I didn’t miss it at all,” she tells me. “But I did have a nervous breakdown.”

An onset of clinical depression forced Fraser to take a year off school in recovery, which she spent, in her words, “holed up in a dark little basement in London.” It was during that year off that she called composer James Weeks and proposed starting a vocal ensemble—she was still not yet a singer—focused exclusively on new music. The beginnings of EXAUDI, one of Fraser’s most prolific projects, effectively came in the midst of a depressive spiral, marking the first of what she calls the “significant chapters” born of intense periods of discomfort and crisis.

I tell her how rare it is to hear a musician speak so openly about their breakdowns; we tend not to focus on trials when describing our careers.

“It’s not something you put on a CV!” she chuckles. “But I feel really tender towards mine. These breakdowns, in my opinion, are the most special opportunity to change things, to rebuild. Who wants to be a fixed entity from the age of 15 through to the end? It’s impossible. We need to have moments of reckoning and moments of collapse when you recalibrate and make change, not just because something’s wrong, but because you have evolved enough to say: ‘I need things to be different.’”

“I need things to be different” became the refrain of our conversation—it is, in many ways, the theme of Juliet’s life. She is, for example, the rare singer to have actively sought a career away from the opera house. “I would always say yes to an invitation to go to the opera, no matter what it is. But that’s me as a listener,” she says. “Me as a vocalist? I don’t think that’s where I want to go, though it took me a very long time to figure that out. I think really up until about a year ago I was still under the clutches of this pervasive idea that opera is the end goal for every classical singer, that you haven’t really made it until you get there, and that if you’re not doing it, then it’s because you’re lacking in some way.

“But ironically,” she continues, “it was when I got an invitation to do quite a big, exciting opera that I had to confront this conflict within me. There was part of me that was going, Oh, my gosh, this is your moment to arrive! And there was a bigger part of me saying, This doesn’t feel right, I don’t want to work in that way. I don’t want to be part of a process in which sound isn’t the absolute priority, and in which the structures are so hierarchical that I inevitably will have less agency than I’m fortunate enough to enjoy in most of my work. It was a pretty dark night of the soul trying to figure all that out within myself. But it’s brought me great clarity, and I’m now able to articulate these things which I wouldn’t have been able to articulate if we were talking about this a year ago. It feels like a relief, actually, to remove this terrible, terrifying goal which I never really wanted. To see it go poof, gone. It’s brilliant.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

We spend much of the conversation talking about escape tunnels from under the overwhelming dominance of opera-oriented singing. Fraser has the most to say about this—beneath all the other tendrils, she is, at her core, a singer, if an unconventional one.

“With classical repertoire, there’s such a burden of accepted practice and performance history and recordings and icons that have gone before us: it’s inescapable!” she says. “The beauty of the [contemporary] repertoire is that we’re free from that. I think the expectation is that we bring something new to it. And that newness isn’t just about interpretive decisions but about our very unique identity and our very unique sonic identity.

“If I understand one thing about this corner of classical music,” she goes on, “it’s that it has no interest in identikit singers. That serves nobody. So, even if we’re talking about, for example, repertoire by Rebecca Saunders, where there are very clear instructions about what you’re actually delivering, nonetheless, the thrill would be listening to a different body and a different personality interpret that with—I maintain, always—the required rigor. But there’s plenty of space in that for individuality.”

“Do you think it would work the other way around?”

Fraser is doubtful.

I say: “I’d love to hear you sing… I don’t know… Bellini?”

At this she lets out a barking laugh. “Oh no you wouldn’t. I know what that sounds like. No you wouldn’t… And I’m just not interested in going there. The rest of the world wants to sing that stuff. I’m on the hunt for a bit more liberation, but also a bit more integration somehow. I think I’ve enjoyed being able to flip in and out of the classical sound and something else, a different sort of vocality, whatever that is. What interests me now is trying to stitch everything together into something a little bit more holistic.

“Having said that, though, the fact that I didn’t have the intensive years of bel canto training that most people have in their 20s means I’ve probably always been singing with a bit more flexibility-slash-inconsistency,” she continues. “I guess I’ve just chosen to embrace the benefits of that and not get too neurotic about the potential deficiencies. But also, I think there’s a danger in getting too cerebral about stuff. I want to try and get a bit more instinctive about the stance that I’m taking, and in some ways less analytical and categorical, deciding between bel canto or belting or pop or whatever… So while I think there’s a great advantage in looking to other genres and aesthetics and vocalities for inspiration, I want to try and break down the walls between them rather than keeping them in those silos.”

On the industry as a whole, Fraser is more enigmatic. When I ask about her relationship to recording—her discography is considerable—she directs her immediate ire not towards the act of recording itself (though she professes to hate that too, and tells me of a recurrent nightmare she has involving continuous surveillance), but to the pervasive fetishization of newness that raises the premiere above all else: “What gets my goat is that it’s nearly always the premiere, the one recorded by the local radio station, that becomes the archive ultimate, when you and I both know the first performance is nearly never our best. It can’t be, it’s totally implausible, there’s too much rollercoaster energy about it, nothing has matured. And what frustrates me most is that the lack of time comes down to economics more than anything else.” She adds, “I think there’s also this cult of the premiere.”

I ask her why she thinks that is. “Compare it to something like a Liszt piano concerto,” she answers. “Nobody would burst onto the scene giving their first performance of the Liszt at some major festival. It would have been with them for at least five years through conservatoire and baby competitions, so they’ll have traveled with it for a bit. And I think because of that classical tradition with repertoire, new music has tried to position itself as an antithesis. We have to defend what we do differently, and I suppose what we do differently is that we specialize in the creation of new pieces. This word ‘new’ pops up again and again. New is what is celebrated, like an Olympics of quantity. I think we need to get more excited about the fifth performance or the tenth performance.”

“So maybe it’s about changing the language,” I offer. “When you explain these things to young artists, how do you go about changing the way they think and talk about the field?”

Fraser’s eyes narrow in playful suspicion.

“We’re talking about VOICEBOX, aren’t we.”

Even in a profile on her personal work, Fraser is intensely concerned with sharing the spotlight. She set out two terms for our interview: that I promise to balance the references to established composers with a mention of Newton Armstrong’s recent solo voice piece for her, “The Book of the Sediments” (“he’s absolutely woeful at his own promotion, so I have to do all the heavy lifting”); and that we talk about VOICEBOX, which has just had its first session, an experience about which she gushes (“I really never say this about anything, but it was better than I even dared to dream.”) So, true to my word, I offer her an in. She jumps at it.

“I think the key is to help somebody unlock their own desires,” Fraser says. “Given that you have to badly want to do this as a career, that you’re unavoidably going to engage in struggle, I think it’s important to be clear about what it is that you want to do. It’s complicated to be a contemporary vocalist. On the one hand, we’ve inherited a tradition of the classical voice which is quite a narrow model, so the likelihood is that a youngster has been trained to try and become a particular thing, to sound a particular way, to aim for a particular thing.

“Normally, the point at which I encounter them is when they’re coming out of those straitjackets,” she continues, “they’ve figured out that the classical voice doesn’t sit entirely comfortably with them, and that there might be another possibility. But at the same time, they’re then encountering a world which, in a way, wants them to be anything other than that, right? So I try to guide them towards articulating who they are as an artist, what matters to them, and what their ‘aesthetic’ is. If they can articulate that, they can resist being drawn towards people that they actually don’t have much in common with or [who] are just going to waste their time.

“The thing I encounter again and again,” she goes on, “and the reason I started VOICEBOX is people feeling lonely as artists: people feeling like misfits, like they haven’t belonged somewhere. That’s how I feel, definitely. So I suppose my message is: come! Come and join this family where the one thing you have to be is a misfit, and where you’re just one of plenty of people who are looking for something different and for whom the dominant model of the classical voice doesn’t feel like home. Let’s see if we can help you figure out who you are.

“Inevitably, that figuring out requires quite a lot of questioning. It’s not enough just to say, ‘You’re singing an E and not an Eb.’ I’m not interested in working on technical stuff except as a means to an expressive decision or an aesthetic decision. What it really comes down to is always knowing why you’re doing something. I find myself asking ‘why’ a lot, even in my own practice: ‘Why this piece, why that decision, that color, that choice?’ The answers that we find from within are what differentiates us as artists.”

Except that sometimes, the answer that comes back is “I don’t know.” The knowing ebbs and flows, and changes too: this, Fraser knows. Her own “I don’t know” has taken on the easy confidence of someone who has long since come to love leaning into uncertainty, someone who knows to take doubt and discomfort as a gift. Even still, I press her on a bit further.

“How do you grapple with the not knowing?”

She sighs for a moment and thinks. When she speaks again, her voice is quiet and unprotected.

“That’s a long-term project,” she says. “Maybe it connects in my mind to surviving a nervous breakdown and to managing being a periodic depressive. I think I’ve developed a skill for sitting with uncertainty and waiting to find clarity within myself. That’s why I outline my life in chapters, because the threshold between each of them was always deeply uncomfortable. There was a lot of frustration that made me want to leave something that was secure and move into something different. And of course, a lot of trepidation, and then a lot of courage, not to mention uncertainty and insecurities of all sorts.

“I guess, for now, my job is to be a singer: that’s what I’m paid to do, and I’m not in a hurry to stop. But I’m very aware of the number of people who could take my place when I’m ready to step off, whether it’s next year or in 20 years. So when I do decide to stop, I’ll do so with such pleasure, knowing that there are people who will do things better, differently, and with a renewed energy and more joy and all the rest of it. For now though, I’m definitely asking myself what sort of singer I want to be. I’m in one of those threshold periods of reflection and change. There are going to be changes for sure. I’m not quite sure what they’ll be at the moment.”

“I’m looking forward to finding out,” I say.

“Me too.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.