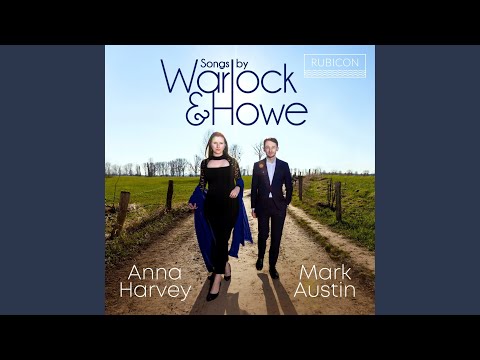

When pianist Mark Austin began researching composer Peter Warlock, ahead of recording an album of his songs with the mezzo-soprano Anna Harvey, Austin focussed on the music and not the life. “I started to read a biography of Warlock and I got about halfway through,” he says. “This is unusual for me, as I’m normally fascinated by context. But I realized that the more I learned about him, the less it was helpful with regards to interpreting the songs.”

Some life stories of musicians threaten to overshadow the work. Such is the case with Peter Warlock, born Philip Heseltine into the establishment at The Savoy Hotel in London, 1894. He worked as a rabble-rousing critic first, and then became a master of small-scale composition. His death by coal-gas poisoning in 1930, aged 36, is presumed to be a suicide, although the jury at the inquest recorded an open verdict.

Warlock remains a fringe character in English music, but he survives, and is possibly thriving as we approach 100 years since his death. There are tangible reasons for the continued interest—new recordings and performances, a steady drip of radio programs, usually made by the BBC, and an organization formed in 1963 dedicated to keeping his music and name alive, The Peter Warlock Society. He’s also propelled forward by occasional flashes into the mainstream. Rob Young’s 2010 book, Electric Eden, placed Warlock in a wider history of English pastoral and folk music, thereby introducing him to music fans more used to Nick Drake and Fairport Convention than art song and serenades. More recently, a trashy-but-fun Classic FM podcast picked up on a rumor, started by his son Nigel, that Warlock was murdered. The podcast may have gone largely unnoticed if the series from which it was taken, “Case Notes,” hadn’t won Best True Crime Podcast at the 2019 British Podcast Awards.

Sometimes, Warlock emerges from unforeseen directions. Better known in Britain than Warlock was the acidic art critic Brian Sewell—a staple on TV in the 2000s—who died in 2015, soon after revealing that Warlock was his father. “My father was sexually voracious, happiest with three in his bed—men or women,” he told The Guardian in 2012. “His tastes ran to sadism and were said to include flagellation. But the thing that appalls me is that his remedy for pregnancy was abortion—without hesitation. He just waved a £5 note at my mother and told her to get on with it. The only thing I like about my father is that he took pains to put his young cat out before he turned the gas on. I will forgive him everything for that.”

Most real-world connections to Warlock now exist two generations apart, with grandchildren. But there are a few closer link-ups. Over email, I speak to Natasha de Chroustchoff, whose father Boris met the then-Philip Heseltine at Oxford University just before the First World War. “I believe they remained friends for several years and after Oxford shared a London flat for a while, together with an Indian man servant who cooked for them. They shared many of the same friends in what must have been a fairly restricted social set of what are now called bohemians, frequenting The Café Royal, The Plough and other Bloomsbury and Soho pubs and restaurants,” Chroustchoff says.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Those friends included D. H. Lawrence, who based two characters in his 1913 novel Sons and Lovers on Warlock and Chroustchoff. Warlock fell out with Lawrence, as he did with many of his friends, and he came to blows with Chroustchoff, too. According to Barry Smith’s 1994 biography, Warlock, already married, once urinated on a drunk Chroustchoff after squabbling over the woman who would become Chroustchoff’s first wife. (Natasha is a daughter from his second marriage.)

Is this true? “The background is complicated,” says Natasha. “Heseltine was staying with D. H. Lawrence in Cornwall when he spotted an attractive young woman, Phyllis Vipond Crocker, bicycling along the lanes to modeling assignments with locally-based artists (Alfred Munnings and Laura Knight, in particular). He wrote her letters and strove to get to know her.” But, Natasha continues, “It was my father who Phyllis ‘chose’ and they married in 1921… I think one can assume that Heseltine was seriously miffed and may have carried a grudge. I believe the putative event happened in the churchyard of St Giles-in-the-Fields when Boris was snoozing on a tomb after a drinking session.”

For the bohemian set, it was a hedonistic time. Included in Warlock’s circle of musician friends was his hero Frederick Delius, who contracted syphilis and died blind, and the conductor Eugene Goossens, whose later career in Australia ended when 1,166 pornographic images and several rubber masks were found in his luggage at Sydney airport. Warlock was known to drink heavily and experiment with drugs, ride motorcycles naked, and indulge in S&M; he adopted his pseudonym after becoming fascinated with the occult while living in Ireland during the war. The stories of his outrageous behavior have filled many biographies and articles in music magazines, sometimes at the risk of devaluing his music. It annoys contemporary researchers into Warlock’s life, and not least because there’s a growing suspicion that perhaps he wasn’t quite the hell-raiser he’s made out to be.

In fact, there’s evidence that contradicts the myth. Pathologist Dr. R. Bronte, who conducted a post-mortem, concluded that Warlock was “definitely not chronically alcoholic.” We know from Warlock’s own writing that his interest in the occult—a voguish pursuit among the English upper classes at the time—was connected to transcendence and unlocking his innate creativity rather than striking a Faustian deal with the devil. And it is those folks who work tirelessly to keep Warlock’s music in print, the staff of The Peter Warlock Society, who understand best how prolific he was at times when it’s easier to assume he was chasing women or legless in the pub.

“The trouble is that Warlock liked to promote himself as a monster of depravity, so it’s all his fault!” says the society’s chairman Michael Graves. “It was obviously a very colorful life, but an awful lot of the stories have been exaggerated and, if not exaggerated, they’ve been put to the fore. He obviously did have drinking binges now and again, but if you look at the amount of material he actually wrote—music and musical criticism—it would be impossible for a soak to have done all that.”

Graves points to Warlock’s time cohabiting with another composer, E. J. Moeran, in Eynsford, Kent in the 1920s. Many of the more insalubrious tales from Warlock’s life originate from his years in the village. Judging by a limerick he penned, he never expected to make it back to London:

Here lies Warlock the composer

Who lived next door to Munn the grocer.

He died of drink and copulation,

A sad discredit to the nation.

And yet, as Graves says, “In the late-1960s, I spent some time in Eynsford and talked to people who had known Warlock during those years. The son of Munn the grocer, who was the new Munn the grocer at the time, described the hype as being largely untrue. Many friends of Warlock’s came down at weekends and there were definitely some serious drinking sessions. But when you consider his amazing output at that time, compared to E. J. Moeran’s, one wonders. Moeran was much fonder of drink than Warlock and he wrote virtually nothing during those years. It is testament to Warlock’s seriousness and mostly sober existence that he achieved so much. I also spoke to Munn’s sister. She confirmed Warlock’s industry and recalled him composing at the piano in the summer months while she sat on the window sill. A couple of old chaps in the village said that most of the time Warlock was sober and hard-working.”

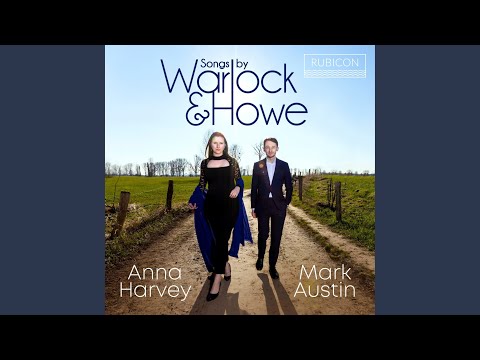

For the musician who pores over the nine-volume critical edition of Warlock’s music searching for a gem to record, there’s a further narrative to consider. “He was constantly experimenting,” says Mark Austin, whose album with Anna Harvey matches 21 Warlock songs—two previously unrecorded—with nine arrangements of English folk songs by Frederick Howe. “The early songs show a mastery of a late-Debussy style, then he moves on, showing the influence of Celtic and folk music. By the end of his life, he was writing in more Elizabethan style, with anguished, atonal harmonies.”

Warlock was a musical explorer, on a journey cut short by his early death. And possibly, because he never settled on a harmonic language—something easily identifiable as Warlockian—his position in the repertoire has suffered.

“He’s known for a small number of works,” adds Austin. “A lot of people love his Christmas music for choir, which is still very famous. There are a few songs which are often-performed, like ‘Sleep’ and ‘The Fox,’ and, particularly for string players, there’s ‘Capriol Suite,’ which all young string orchestras play in Britain. He’s definitely there in the minds of musicians, but he’s not a mainstream composer. He clearly had a difficult personality and multiple identities, and you could connect that to his slightly anguished exploration of different styles. Perhaps, from what we know about his extreme existence and sadomasochistic tendencies, you could argue that the music doesn’t live up to his life, but I don’t think that’s the case.”

“My take on this is that it’s to do with him writing mainly songs and some chamber works,” says Harvey. “It’s not so much that Warlock isn’t recognized, it’s that there’s a lack of recognition for small-scale works and how you can tell a whole story and evoke many sound worlds and colors in a three-minute song for just a voice and piano. In that genre, Warlock is an absolute master; a master of the miniature.”

Michael Graves believes a tide may be turning. “We’ve seen a lot more activity in the last two or three years, with regards to concerts and CDs that include Warlock,” he says. “For a long time, you’d hear the old favorites in a song recital—perhaps ‘Sleep’ or ‘Captain Stratton’s Fancy’—but now we’re seeing that performers are choosing lesser-known works, which is great.”

Graves considers it his job as the new-ish chairman of The Peter Warlock Society to “not exactly tone down the exotic, wild side of his story but rather more to balance that against the other side—his hard work and productivity.” He may be fighting a losing battle. There are stories he tells me that drop kerosene on the myth—particularly one about Warlock being taken home in a wheelbarrow, drunk, by the station porter at Eynsford—and in the newsletter that he edits and sends out to the society’s 180 or so members, continual intrigue. There’s nothing concrete to prove that Warlock was murdered, but the Autumn 2018 edition features a recently unearthed letter, written by the composer Rebecca Clarke, questioning the view, based on an eye-witness account, that Warlock let his cat out before poisoning himself with coal gas. And what journalist could possibly resist a theory that perhaps Warlock died in a tragic accident, just as he reached his maturity as a composer? ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Correction, 8/14/2022: A previous version of this article described Michael Graves as the president of the Peter Warlock Society. His position is chairman. VAN regrets the error.