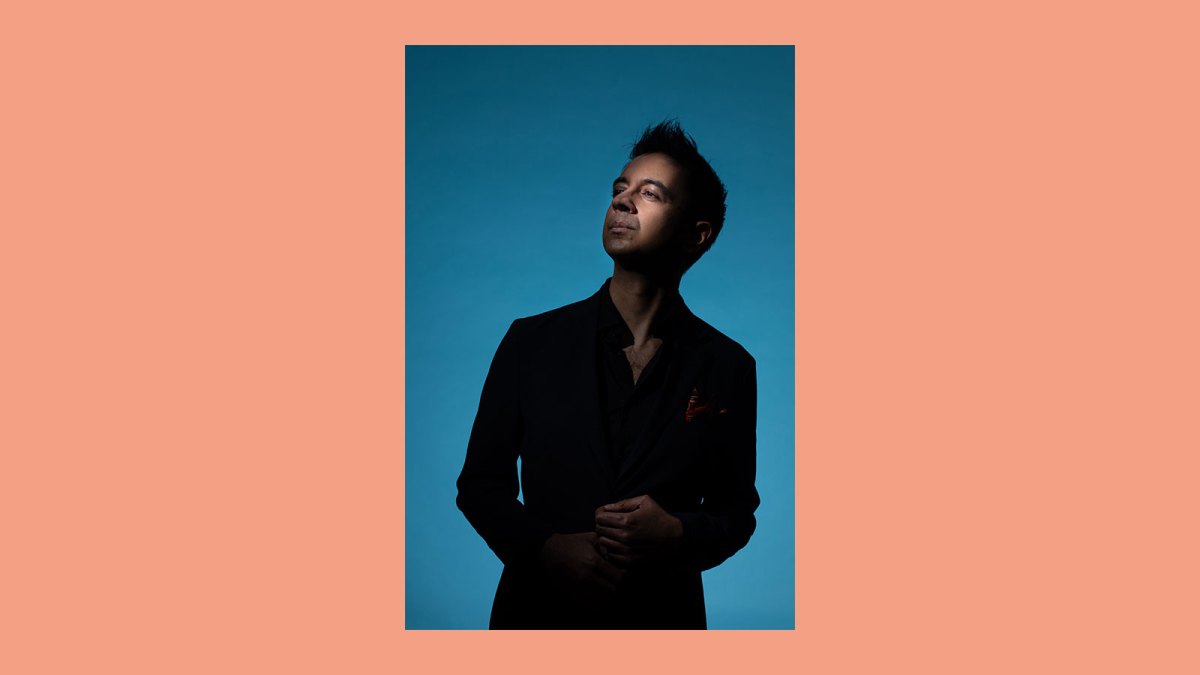

At Wigmore Hall in November, a solo piano recital by Vijay Iyer was like a set of rough clouds in a humid summer, breaking in brief, awesome moments. Hearing “Love in Exile” at the Barbican a few months earlier, the trio (Iyer, Arooj Aftab and Shahzad Ismaily) made a thick haze like a hot-warm drunkenness. Iyer’s music, something music journalists like to describe as cerebral, has a palpable sense of feel and feeling, particularly of late. It’s often complex music, emanating from complex bodies.

Iyer wrote his first piece for orchestra when he was 35. His first album of orchestral music, “Trouble,” was released on the BMop/sound label on June 11. We spoke on that day, as he was midway through a new piece for the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival in Connecticut, scored for Pierrot ensemble and percussion.

VAN: You took lessons in violin and played in chamber music and orchestras up to the age of 18. What did you take from that time?

Vijay Iyer: Well, certainly an appreciation of what players are dealing with when they’re confronted with a new piece, and also what it feels like to play in an ensemble: about how we synchronize, how they play together, in tune, these kinds of very basic things which are actually, to me, the real core of what music is. The fact that we can do that—that we can move together, that we can match each other, that we can feel together—all those things make up the essence.

Being among variously sized masses of people, whether it was a string quartet or a 100 piece orchestra, I think I just got a lot of the hands-on feeling of…. how should I put it… being alive in music, let’s put it that way.

Did the impulse to write music down come naturally to you?

Not really. I remember taking some music theory courses and stuff when I was 12 years old… I was starting to make music, create music, but writing it down was not a big priority for me until I started leading my own groups when I was in college, when I was 18. That was when it was like, oh, I need to write something down for someone else to read.

[Notated music] was mainly in a jazz context—trios and quartets that I put together when I was in college. At that point, I was trying to imitate or channel what I was hearing from the music of Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane and quite a few contemporary players of that time: Geri Allen was a huge influence on me, starting in the late ’80s. Joe Henderson, Dave Holland…

The more spontaneous music that you’re involved in always feels very personally active—it’s reacting, proactive, it’s kind of telepathic, and all of those elements really feel encoded into the musical results at the end. When you compose for means like an orchestra, which are more static, do those principles of activity change? Do you try to maintain them and try to recreate that feeling, or is that futile?

Because the first things I wrote for classically trained musicians were pieces of chamber music—what I said earlier about the feeling of being alive in music—when there’s a real interdependence, in the context of the chamber ensemble, it’s not that different a feeling from what we’re doing in one of my bands. Certainly, the terms of order are different, and what the musicians are thinking about is different, but what it feels like is actually not that different. So I think I’ve built outward from the feeling of chamber music.

So my first orchestral piece, “Interventions,” had these chamber moments in it that were actually real time—I won’t say improvised, I won’t say indeterminate, but sort of real-time decision-making processes, processes, among small aggregates within the orchestra. I wanted to preserve that feeling: both the feeling of interdependence, and sort of the “step into the unknown” feeling, which really pins the whole ensemble to the present moment.

I recently had some pieces taken up by some choreographers, including someone with the New York Ballet. They took one of my older string quartets, “Dig the Stay,” and choreographed a pas de deux for it. It was wonderful to see, people really embodying what’s happening in the music in this way that’s so alive and so visceral, you know? And it became clear to me, this is actually a nice way to listen to music, through dance.

I was talking to my friend Teju Cole about it. He said that dancers latch on to music in different ways to how a lot of music people do. He said, they like Bach but not Beethoven… they like figures; it needs to keep evolving, to keep moving, to have an available logic, almost like the building blocks have to be apparent immediately, then you can start building with constituent parts. That quality appears in some of that piece.

I’m interested in a point in the booklet about the kinds of works that you’ve been asked to write—commemorating “The Rite of Spring,” writing an overture to a Bach cello suite. As well as reproducing and solidifying an existing structure (as you note there), do you also see that commissioning process as a wider market trend too? That “let’s make something based on an existing thing” model is huge in film and TV—the Barbie movie, “Dune,” the Marvel franchise, the IP work—but it hasn’t been consolidated as a way of thinking about classical music yet.

What it does for classical music is assure people that there still is something that they can call “classical music”—not an abandoning of a category, but an expanding of it. Last time we spoke, I told you what I thought about all of that…

It’s easy for me, having spent plenty of time playing and studying classical music, to say I have no need for that category. But it’s more that I at least want to apply pressure to the category: why we still need to call it that, why we need those assurances of continuity with some fantasy about Europe’s past.

We don’t do that with many other art forms. There aren’t many other creative forms that are so concerned about their own histories that they have to keep assuring each other that they’re still in dialogue with the past. In most other artforms it’s taken as a given that that speaks through you. It’s not like you need to convince somebody that if you’re using paint and a brush you’ve abandoned the tradition of Cézanne or Degas or whatever. It’s a weird fixation; George Lewis described it as an addiction.

When I say weird, it’s not weird, it’s actually pretty predictable: the fantasy and continuity with Europe is kind of cultural-nationalist and essentially white supremacist logic, and so for those of us not in it, to have to assure people that somehow you care about it? That’s the strange dynamic, even though I’ve capitulated many times—I’ve played along—and it was productive for me in these various ways to inhabit or at least bounce ideas off some of the works of the past. But it’s not like I need to keep doing that to prove something to somebody.

At this point, I’m not mad at having done that, I just found it amusing that it was this ongoing trend. But I think it has to do with being in North America specifically. That’s where that fantasy of continuity actually needs to be continually propped up: The reason we have orchestras in North America is because European music is great. Is that the way to justify all this? And then, who buys into this [narrative] and why? Rather than to say, well, there’s a global heritage of music making that belongs to everybody, and here’s one way that some people have done it… We can build on it without having to participate in that fantasy.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

In the liner notes, you describe the distinction between improvisation and composition as “sending something downstream.” I was also interested in your reflections on the particular moment of 2016 to 2019 from which the works on the album—“Trouble,” “Asunder” and “Crisis Modes”—derive, and some of your own ideas around American nationhood that you no longer subscribe to. Looking back at these works from downstream, how do you perceive works that speak of a moment, parts of which you now reject?

I will still play pieces I wrote 30 years ago, and what I find myself doing in those moments is integrating a certain past version of myself into the present. It’s not like I’m pretending to be younger or something, but often, the ingredients in that music might have a different focus and a different purpose in the way that was put together. The ones that I end up adopting often are the ones that are the most sentimental, actually, so it is a sort of nostalgia when I’m revisiting those older pieces. I don’t reject that past, even if I’m somewhere else now. It’s more that the sense of urgency is different for me now.

Whenever I write something, it sort of needs to have a reason for being. I can’t make music just as an exercise. So understanding that my sense of purpose has shifted, I can still appreciate the ingredients and the methods of music making that were part of those past selves. It’s almost like it can be a little mysterious to revisit a piece you made years ago. And you start asking yourself, What mattered to me then, and what matters to me now, and what might my new priorities be?

“Trouble” has a sort of allegorical arc of some kind that has to do with something about the individual subsuming into the aggregate through a ritual of bearing witness. I can understand why I had to put it that way to construct something for myself. But we’ve been surrounded by mass death for the past four years. What is the next step in an allegorical framework, having born witness ad nauseam? There’s no time to waste, there’s barely any time to linger. The urgency of the moment makes me create differently now.

The piece you’re writing at the moment… You were talking about pieces needing to have a purpose in order to be. What is its purpose? Do you see a moment that you’re responding to?

The piece is called “Variations on a Theme by Ornette Coleman,” the theme being “War Orphans.” There are multiple covers of that piece, because Charlie Haden shared it with several of his contemporaries after those years with Ornette. I found an early recording of Ornette and his group doing it in the early ‘70s, and it sounded really different, radically different from all the versions I had heard.

In particular, it has that urgency, an exuberance, a forthright quality. It’s pretty hectic; it has this kind of super-intense polyphony happening that is a little terrifying, even though it has sort of a theme that could be interpreted in a more pastoral way. (The way he plays it with the group is not pastoral whatsoever.)

That to me is the difference, that’s what it boils down to. What feeling do we want to share and instil in others right now? And I think the feeling is urgency. You know, the feeling is not joy, it’s not satisfaction, it’s not stillness, it’s not those things, it’s something else.

And so how do you manage that, through the course of pages and pages of notated music without saturating it to the point of being impenetrable. How do you kind of carry a listener to that place of urgency? That’s the real challenge. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.