In his work, the writer, photographer, and critic Teju Cole intersperses references to art, literature, history, and—often with particular beauty—music. In his debut novel Open City, for instance, the narrator muses about Gustav Mahler’s compositions: “I thought about how clouds sometimes race across the sunlit canyons formed by the steep sides of skyscrapers, so that the stark divisions of dark and light are shot through with passing light and dark.”

I met Cole one recent afternoon at his office in Brooklyn. He put on Philip Glass’s “Opening,” then the Finale from “Satyagraha.” There was a loud beep. “Our fire alarm needs its battery replaced, so it’s going to interrupt us,” he said. We spent the next hour and a half listening to and talking about music. He mentioned that he feels like he’s not supposed to like Philip Glass.

VAN: Why is that?

Teju Cole: Because it is instantly there. It is too available, which raises a question about its sophistication.

Too available emotionally?

Right. And even technically, you can get a sense of what he’s doing. And yet it seems to have this core that sustains it emotionally. I can’t quite figure it out. I really like Radiohead for example, and of course there are differences, but something about this music gets me into the same head spaces as Radiohead. Or even Bach solo violin or cello. Because of the ostinato and the instrumentation, it feels trance-like.

Part of the problem is that [Glass’s] language got so successful that it became the default language for film soundtracks. For example, nobody is really using Peter Maxwell Davies’s “Organ Voluntaries” for film soundtracks, and it could work just as well.

In your book Open City, the narrator Julius hears a piece by Maxwell Davies while visiting a church in Belgium.

That’s interesting that you say that: It’s this piece. It’s a total coincidence, because I’ve not even listened to this in a long time.

It’s not so distant [from Glass]. But already there’s an intellectual engagement of a different kind. Because you’re trying to figure out what’s happening in that other register, which is cross-wise to the underlying regular English church melody.

George Benjamin, “Three Inventions”; George Benjamin (Conductor), Ensemble Intercontemporain

George Benjamin’s “Three Inventions” is a pure and sensual pleasure for me that works in a way almost opposite to the pleasure I take when I listen to Philip Glass. I would not necessarily have Benjamin on while I’m walking around or on the subway. This is something for sitting and listening closely to on my headphones.

Benjamin is an incredible colorist. He sounds very French. And yet the structure is so good. By the time you’ve heard this 10 times, it makes just as much sense as a Mahler Symphony.

Have you heard in 10 times by now?

Sure. I first got a CD of it 20 years ago. It’s just a piece I love; that combination of structure and color that really makes me think of him as a great composer. What I love about this is that if it’s referring to anything out in the real world, it’s almost like a voyage of discovery, something primordial. It’s swampy. That bassoon, that grr, there’s a crocodile moving through a swamp. I like that. I also like that it’s not referring a lot to culture.

You like the sense of abstraction?

Yeah, but that abstraction… it’s not completely abstract either. It still calls on metaphors like the crocodile. In his case it’s not clouds moving, it’s something heavier than that, it’s something more intricate and weightier. But there’s a sense of something moving: like a boat moving through the dark, flashing points of light.

Which I find is also true of music by Robin Holloway. It’s almost a perfect bridge between Mahler and Benjamin. You can still hear the flow of the musical argument, it’s unbroken, but with some of the contemporary gestures that Benjamin also uses. And again, it is an abstraction that still has a feeling of a journey or discovery. You feel like you’re on a boat, you’re moving and the vista is changing in front of you like you’re in the Amazon, and suddenly you’ve just come upon your first anaconda. [Laughs.]

Pieces by Mahler come up in each of your books, Open City, Every Day Is For The Thief, and Known and Strange Things. Is he your favorite composer?

My favorite composer is Brahms.

That’s surprising to me—tell me about Brahms.

What I should tell you about is fiction. When you’re doing fiction you give to the character something one or two steps to the side of what is your own core. Fiction works through all those distances. If I had made it about a character who loved Brahms and also listened to a lot of hip hop and jazz, then it’s too close to me and I can’t do what I need with him, fictionally speaking.

I really love Mahler’s music, but to make Julius into a complete Mahler obsessive was my way to create a little bit of distance between us, in Open City. In Every Day Is For The Thief, that’s a fictional character that is a little bit closer to me, but still fictional. And the Mahler reference in that book was a passing reference.

What can I say about Brahms? The thing about him being my favorite composer definitely has to do with the kinds of games that boys, in particular, like to do. We like to rank our favorites. It’s an imperfect activity, by definition, but it’s fun—it helps you to organize your world and your head. We move through life with the help of our favorites.

And I mean probably the three desert island composers for me are—well, I should say the four, it’s hard to pick the three—the four would be Brahms, Beethoven, Bach, and Schubert. And I feel like you know, Beethoven is a pretty firm second to Brahms.

What can I play you by him? Maybe something very simple that you might not know.

This is a song that you hear and you’re like, “That must have always existed.” Two things move me about this. The two female voices duet thing is a bit unusual, but also it’s “Die Meere”—“The Seas,” not “The Sea.” I don’t know what the words say, but that’s a very strange texture of thought.

I think because of his appearance, his beard, and the name Brahms, you know, people associate him with a certain heaviness; but the melodies are actually so light and open and joyous. Not soufflé light, like Mozart or Rossini, but simultaneously light and intricate like a race car or a running brook. I’ll play you just 30 seconds of something else of Brahms, and this is something you know. But now I want you to think about it in the context of what I just said.

It’s as beautiful and consoling as “Sheep May Safely Graze.” That pastoral feeling he completely nails, but there’s all this additional complexity.

When did you first start listening to classical music?

I’m not educated in it at all. I grew up in Nigeria, and I was there until I was 17 years old. [I heard] a bit of classical music passively, just because my dad had some LPs lying around. There were some compilation cassettes in the car that we’d hear on the way to school. There would be a Bach Sonata, followed by smooth jazz, or whatever. I certainly did not think of it as a separate category of music, and also there was not a whole lot of it.

But when I came to the U.S. for college, my inner autodidact kicked in, and I became fully absorbed both in jazz and classical music. I remember my two most intense initial experiences were with Mahler and Beethoven. I had a Beethoven’s “Greatest Hits” tape that I bought from Walmart, and I just wore it out with repeated playing. And I think this was my first experience of repetitive listening that didn’t settle down into a simple pleasure; that always revealed new information. With pop music, after a while you’ve heard what’s in there, and you listen to it again because it’s a reliable pleasure. But the experience of listening a 12th time and discovering a new instrumental line, or a new piece of the compositional logic, was new to me. And I sort of fell in love with this layering, this endlessness, of great composed music. By 1996, the only real ambition I had in life was to have three recordings of every Mahler symphony.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Since you mentioned Mahler, I do want to talk a little bit about the moment in Open City when Julius goes to the concert of the Ninth Symphony and he’s the only person of color at Carnegie Hall. And afterwards he goes out the wrong door, ends up locked out on the fire escape, and has this deep epiphany.

Is there a potential to feel a deeper magic in the music if you’re feeling alienated and uncomfortable before?

Yes. Julius is given to a certain amount of over-interpretation anyway, he suspects the world of being a bit of a code. The woman who walks out [during the performance also] symbolizes something. It’s definitely a passage that means a lot to me. For me it’s one of the three codas of the book.

This is one of the most specifically musical of all the gestures I’ve made use of in writing. I’ve said before that in terms of the structure of Open City, I had Sibelius in mind. Sibelius is somebody who knows how to deal with different speeds, but who is remarkably consistent in his use of motives within a work. That very much affected the way I approached my various themes, how they got seeded and elaborated, but also the contrast of the undertow versus what’s on top.

Jean Sibelius, Symphony No. 3 in C Major Op. 52; Sir Colin Davis (Conductor), Boston Symphony Orchestra. Cole is discussing the passage at approximately 8’30”.

It’s a very interesting place to introduce silence and gaps: near the end. Somehow that sort of stuck in my head. I thought, “Wow, that’s a very interesting way to end a movement.” He has a phrase that he has them play with the woodwinds; and then it’s reiterated very soft in the strings, and then the full orchestra again, a version of the same phrase. It’s three endings.

In the book, with Mahler 9 and the woman who walks out—that’s a good way to end the book, but it doesn’t end there. Then he’s locked outside and has this epiphany with the stars—that’s a good way to end the book, but it doesn’t end there. And the final one is he gets on the boat and there’s this history of New York City that he has to deal with. I thought of all these three as possible endings for the book; and I decided to use all three.

I can let you in on the secrets a little bit. One is that that concert—Rattle, Mahler 9, at Carnegie Hall, in late 2007—the concert happened. But I didn’t see it. Later, while I was writing the book, I went to see a performance of Mahler 9, at Avery Fisher Hall, I think it was the New York Philharmonic. By then I already knew I needed Mahler 9, so I needed to go to another performance just to refresh myself. And then in that concert, the one at Avery Fisher Hall, an old lady did walk out. But it was in the first movement, not in the final movement. I have also been accidentally locked out on the side of Carnegie Hall before. But it was many years ago, and I think it was after Brahms 4 with the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester.

It was sort of stitched together from these many different things. I usually don’t give away my compositional techniques—people are always asking, “How much is real, how much is made up?” And I say, “Well, we’ll never know.” But in this case, now you know.

Both in Open City and particularly in the conservatory chapter of Every Day Is For The Thief, which takes place in Lagos, I was surprised at how easy you were on classical music, considering its often fraught history.

It makes for a good question. Basically, what’s at stake here is the understanding that what we call classical music—Brahms, Beethoven, Bach, and the tradition they’re associated with—represents one of the central pillars of Western civilization. It’s really close to the core of that tradition. What is the tradition? There’s the music; there are the paintings which are in the museums, which are valued with certain dollar amounts to indicate how central they are to the culture; there is the literature, Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, though I’m not even sure the literature is as central a pillar as the art and the music.

These are the things that are really at the core of not just Western self-description, but maybe even the Western sense of superiority. “Why do you think you’re superior?” “Well, because we have Christianity and we also have Beethoven and Shakespeare and Michelangelo.” This highly formalized and sometimes rather fussy music is valued in a way that is not even quite the same for Western technologies or weapons of war or even of filmmaking, architecture or urban planning.

So from somebody who comes to this music from a postcolonial point of view, it’s already problematic in that way. Now you look at all that and you have to somehow reconcile it with the very profound personal pleasure you take in it.

And how do you do that?

I don’t. I just let it be personal. When I give an account of it, I make sure I don’t give an account of it as being inherently superior to anything else. But nobody’s going to convince me to stop listening to Brahms simply because he’s a 19th-century German guy.

I suppose there’s some kind of responsibility to keep the field of personal experience broad, to listen to other forms of creative music, to have big ears. I also think it’s permissible to be personally selective. Wagner is a wonderful composer, but he’s not very close to my heart. In part because I’m not a big fan of opera anyway, but also because I’ve decided not to give Wagner too much of my time, because I don’t want to spend too much time in his world.

Wagner’s operatic worlds have concrete associations. Do you prefer instrumental music?

To a certain extent. But it’s also connected to the sensibility of the person making the music. Brahms, Beethoven, Schubert—for their time they were very secular, more so than Mozart and Bach, for instance, who had very profound religious feeling. And when it comes to jazz, my number one is Coltrane. Not because he was secular—in fact, he was rather more religious and spiritual than other jazz men—but because his spirituality and Brahms’s secularism are actually moving in the same direction, which is about openness, tolerance, and inclusiveness, and a sort of non-doctrinaire approach that you can almost feel through the music. It is sensitive to spiritual currents without preaching a creed.

It would be weird to listen to “A Love Supreme” and think, “I have to believe this”…

…and that, and whoever doesn’t goes to hell. [When listening to classical music] I feel the same way as Jessye Norman must feel singing Richard Strauss’s “Vier letzte Lieder.”

Richard Strauss, “Vier letzte Lieder,” IV. Im Abendrot; Jessye Norman (Soprano), Kurt Masur (Conductor), Gewandhausorchester Leipzig

I don’t think Jessye Norman feels any separation. She’s there to be fully absorbed into the music. And that’s where I am when I’m listening.

In Every Day Is For The Thief, there’s a sour moment at the conservatory when the narrator is told that white music teachers make more money than the Nigerians. That moment rang very true because I had a similar experience: as a 19-year-old, in Nairobi, someone told me I could get a job teaching at the conservatory simply because I’m white.

We are post Fall, we have been ejected from the Garden of Eden. And everything is toxic. And inside that toxicity now you have to find what isn’t, what helps you along. I would say classical music is a huge part of my life. Thank goodness it’s not the only part. It’s not as if I feel stuck just in the world of old white composers.

Still, somehow, in spite of the fact that [classical music] is institutionalized, formalized, over-praised, and forced down people’s throats, it has in itself a kind of core that can be very intimate and helpful as you navigate your way through your own life.

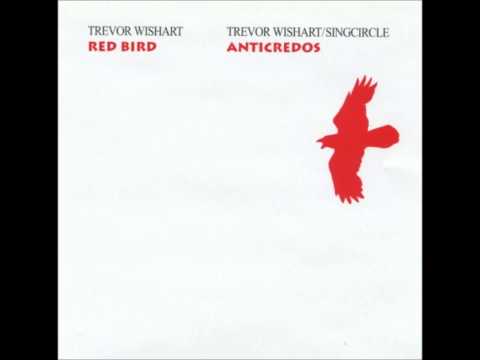

I think I should play you one last thing, Trevor Wishart’s “Red Bird,” an experimental piece from the mid-‘70s. It’s relevant to the present political moment, but don’t hold that against it. ¶

Trevor Wishart, “Red Bird: A Political Prisoner’s Dream”

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.