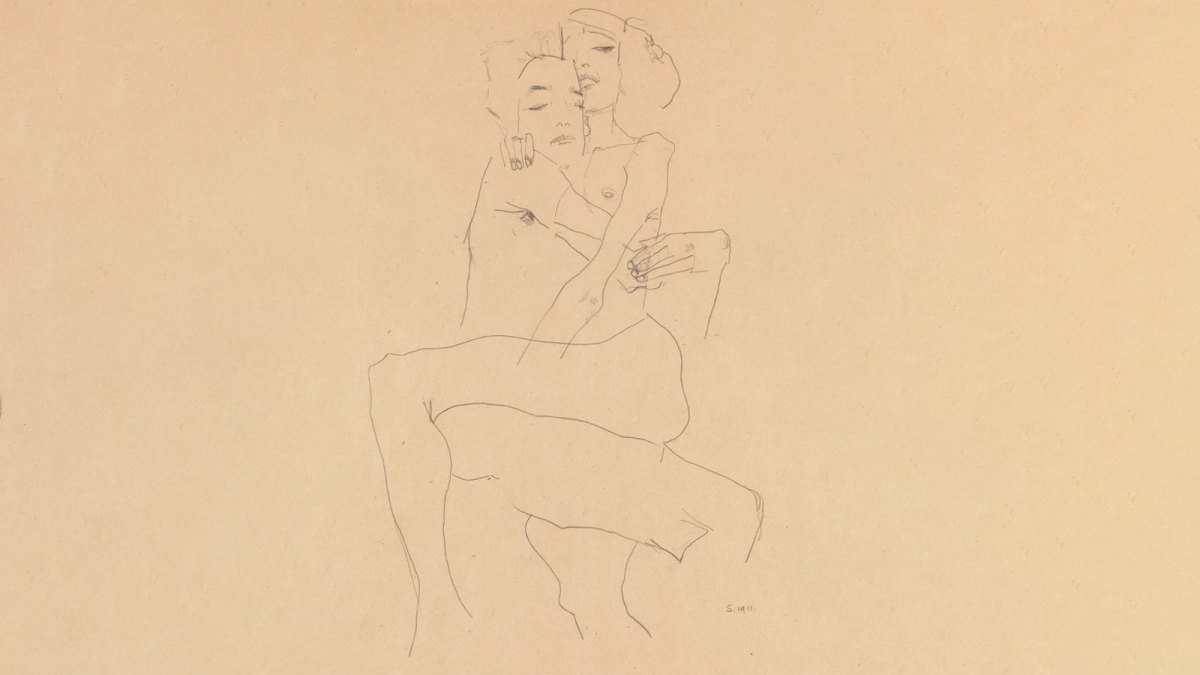

In his dazzling, fragmentary book A Lover’s Discourse, Roland Barthes wrote, “Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words.” When I first encountered this analogy in my early 20s, I felt somehow relieved. I didn’t love literary theory; however, I wanted, without completely knowing it, a theory that linked language and love, and a theorist who wrote with vigor and (ironically) directness about “the state of being in love.” Barthes was the thinker I’d been looking for. He pulled theory out of the ivory tower and made it an investment in the real: in my body and all the inexpressible—raw, stupid, and profound—experiences I was having around erotic and love relationships.

Barthes was born in Cherbourg, a port in northwest France, in 1915. After his father’s death in World War I, Barthes moved with his mother, Henriette, to Bayonne, a small town in the southwest. There he learned to play the piano (his Aunt Alice was a professional piano teacher), and developed a love of the music of Robert Schumann. After eight years in Bayonne, Henriette decided to move to Paris, where Barthes continued to study music: acclaimed baritone Charles Panzéra, to whom Gabriel Fauré dedicated “L’horizon chimerique,” became his teacher and taught him how to “work” a text. Perhaps not surprisingly, he fell in love with another of Panzéra’s students, Michel Delacroix, son of the famed philosopher and psychologist Henri Delacroix. In 1942, when Barthes was 27 years old, he and Michel both moved into a sanatorium to treat recurring episodes and complications of tuberculosis. Michel died in the sanatorium in 1943. Barthes remained there until 1946, claiming he was “happy” thanks to friendships and reading. He fell in love again in the sanatorium, with another TB sufferer, but this time his love was unrequited.

Given his personal history, it’s no wonder Barthes was so attuned to the body. One reason I love thinking about his conception of language as a skin is that it invites some formulation regarding music. If language is a skin, then music might be breath on the skin. According to one of his biographers, Tiphaine Samoyault, Barthes “did not have an intellectual relationship with music”; he viewed emotion, taste, and memory as the only “laws” of musical aesthetics. This mindset allowed him to love Schumann in the “purest” possible way. He said, “I hear [Schumann] as I love him… I love him with just that part of myself that is to myself unknown.” And: “Schumann’s music goes much farther than the ear; it goes into the body.”

A Lover’s Discourse is an atypical or peculiar text, though less so today than when it originally appeared; its publication helped usher in autofiction, but it began as a seminar Barthes taught at the Collège de France. Barthes set out to “essayify” his teaching, and the voice he proffered is and isn’t Roland Barthes. He created a speaker, for lack of a better term, to simulate how a lover thinks and talks about a beloved. This voice is magnificently intimate, but as Wayne Koestenbaum points out in his foreword to FSG’s recent edition of A Lover’s Discourse, the simulation “transcends any specific love relationship (platonic, pedagogic, familial, erotic) that Barthes underwent” and instead describes “the general experience of being in thrall to love’s categories.”

Significantly, Barthes shows that being in love is only ostensibly a private, singular experience—because one’s relationship to a “beloved” is always mediated by the social through the unconscious. As put by Andy Stafford, who, in my view, wrote the most enjoyable biography of Barthes, “A Lover’s Discourse showed how lovers play out a set of social constraints and limited freedoms via a language that is unknown (and unknowable, even) to scientific and humanistic knowledge.”

Although A Lover’s Discourse simulates unrequited love from a lover’s perspective, it can’t be adequately described as a book about unrequited love. It’s more a book about being in love. In an interview with Playboy from 1977, Barthes clarified this, explaining that “common sense tells us”—and this is where A Lover’s Discourse ends—“that there comes a time when one must uncouple ‘being in love’ from ‘loving.’” A person in love might feel “dominated, captivated, possessed” by a beloved, but the person in love is actually the one wielding “tyrannical power” in an effort to get what he or she wants. Barthes posited that the “ideal solution” to this was for the lover to inhabit “a state of the non-will-to-possess,” to “master desire in order not to master the other.” A kind of jiu-jitsu.

A Lover’s Discourse comprises 82 chapters, each headed by a figure or fragment of discourse that is born out of “amorous feeling” and signifies “the lover at work.” “I am engulfed, I succumb…,” for example, is the figure heading the first chapter. Barthes instituted order by alphabetizing them but noted that “no logic links the figures… the figures are non-syntagmatic, non-narrative; they are Erinyes; they stir, collide, subside, return, vanish with no more order than the flight of mosquitoes.”

For this playlist, I’ve attempted to illuminate ideas about love as well as how Barthes dramatized nuance—or “the Intractable”—in A Lover’s Discourse. Since Barthes rejected traditional narrative writing (the Aristotelian beginning, middle, and end), I’ve assiduously avoided any kind of progression. Instead, I’ve made my own attempt at out-of-a-hat “orderliness,” arranging figures, as best I could, to spell out LANGUAGE IS A SKIN.

I agree with Barthes’s final words in Playboy: “One should not let oneself be swayed by disparagements of the sentiment of love. One should affirm. One should dare. Dare to love…”

L – Laetitia

Can I, as a lover, circumscribe moments of pleasure?

Barthes explores this through the figure Laetitia (Latin for “joy”). Referencing Cicero and Gottfried Leibniz, he contrasts Laetitia—“a lively pleasure” that “predominates within us” (among other, often contradictory sensations)”—with Gaudium: “The pleasure the soul experiences when it considers the possession of a present or future good as assured.” The lover, who has no claim on the beloved being and therefore no Gaudium, valiantly clings to Laetitia, thinking I will focus on my pleasure, I will control my feelings, I will forget my discomfort…

I thought of Laetitia when I played Gabriel Fauré’s “Après un rêve” with a friend in May. And not because Fauré’s piece has a drifting quality, nor because I’ve read the poem by Romain Bussine. I was thinking about Laetitia vis-à-vis music-making, especially with just one other person and instrument. I didn’t have strong feelings about “Après un rêve” prior to playing it. “Working” it, however, with another human, I was taken by the piano and string bass lines rubbing against each other. We played somewhat recklessly, or loosely. This was a lively pleasure.

A – “Adorable!”

Why, the lover asks, do I love this person in particular? How can I describe the specialty of my desire?

Per Barthes, I adore my beloved, but when I attempt to explain this to him, I fall back on circular reasoning: “I adore you because you’re adorable, I love you because I love you.” I hit a wall, the end of language.

I have similar trouble describing my fascination with Steve Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians.” What can I say? I love the shape and mood of this piece. The textures and colors. The pulsing. The ethereal sounds of the metallophone. But I’m unable to be specific enough. I can’t properly put my fascination “into words.”

N – nuit / night

Borrowing from the Spanish mystic Saint John of the Cross, Barthes describes two nights. One is the darkness of my desire that keeps me “in the shadows,” where I’m “blinded” by my attachments. The other is “the dark interior of love” or “night of non-meaning,” where desire ripples through me but “there is nothing I want to grasp.”

John of the Cross illuminated these nights in “La Noche Oscura de Alma” (“Dark Night of the Soul”), his poem depicting a spiritual journey toward God. In the poem, the second night—“oblivion,” where “My head was resting on my love / Lost to all things and myself”—envelopes the first. Darkness illuminates darkness, and this is revelation. A union with the unknowable. God.

According to Barthes, the lover—not of God, but of some beloved “Other”—is likewise struggling through states of darkness. If he is lucky, then he’ll “enter into the night of non-meaning.” He’ll figure a way to sit calmly. Decide nothing. Do nothing. In essence, he’ll embrace the Tao.

Day in and day out I commit myself to an unhooked amorous state. I let things happen. I don’t resist, though at times it’s as if I’ve dropped somewhere inside George Crumb’s “Sea-Nocturne (…For the End of Time) Vox Balaenae” and am facing a huge fucking sperm whale. The whale fascinates and frightens me, partly because I can’t look him in the eyes.

G – Glasses (dark)

Should I hide that I love you, precisely because I love you? Barthes suggests this is the lover’s dilemma because the lover sees the beloved with “a double vision: sometimes as object, sometimes as subject.”

If I love you (and can assume you don’t love me to such an extent), then I run the risk of smothering you. However, being that I love you, I care about your comfort and happiness, and I don’t want to tyrannize you. Still, I want you to know that I love you!

Barthes’s compromise: “I will show my passion a little.”

I make my love like Brahms’s Intermezzo in E-Flat Major: gentle but not “light,” passionate but still dignified. Or Chopin’s Berceuse in D-Flat Major, a mostly tranquilizing piece that, in the words of André Gide, “proposes, supposes, insinuates, seduces, [and] persuades” but “almost never asserts.”

U – union / union

In his interview with Playboy, Barthes says, “The lover is the natural semiologist in the pure state! He spends his time reading signs—he does nothing else.”

Why? Because the lover dreams of a union, “love’s fruition.” Wanting fiercely to own the beloved, he can’t make “the signs” stop. He understands the signs (i.e. the averted gaze, the unreturned phone call, the pat, the shrug), but he’s “unable to arrive at a definite interpretation, and he’s swept away by a perpetual circus, where he’ll never find peace.”

The lover’s world might be like Pierre Boulez’s “Le Marteau sans maître”: a dense, esoteric, discontinuous image system. Fittingly, the poems in René Char’s Le Marteau sans maître, Boulez’s inspiration, veer toward the surreal but mostly read like moving symbols without referents.

A – Atopos

According to Barthes, the person I love is “atopos,” meaning he can’t be classified.

He’s someone of “ceaselessly unforeseen originality.” No one can say he’s this or that “type,” because he confounds “description, definition, language.” And yet, as much as I cling to his uniqueness (and the originality of our relationship), I want structure. I want to place myself in a love story so that I might reconcile myself with society. While I desire what’s inexpressible, I want to enter “the sistemati” like “some sort of superior prostitute.”

Ergo, I’m cruising. I think I want something like Ravel’s “Ondine” from “Gaspard de la nuit,” not because of the folklore behind it, but on account of its exquisite balance of craft and strangeness. In “Ondine,” Ravel breaks with stereotypes harmonically and structurally while creating sonically propulsive symmetries and patterns. In a sense, “Ondine” feels as if it’s “on the lookout for its own desire.”

G – Ghost Ship

“How does a love end?” Barthes asks. He answers his own question: “Love which is over and done with passes into another world like a ship into space, lights no longer winking.”

Assuming failure doesn’t kill us (the way it did Goethe’s Werther), we resign ourselves to “another temporality… another music.” We sail from love to love, propelled by “the great stream” of an Image-repertoire, searching for fulfilment.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

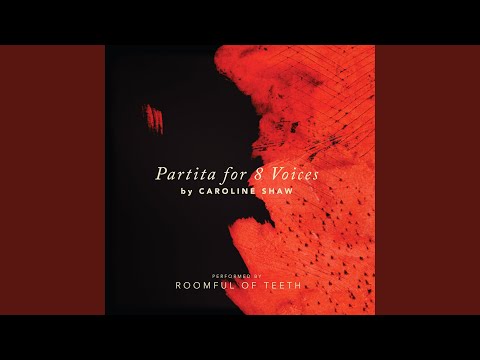

Caroline Shaw’s “Partita for Eight Voices,” performed by the vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth, calls to mind some kind of “ship” from bygone days. The first time I listened to it I imagined scenes out of The Odyssey and Moby Dick. Displaying a range of vocal techniques (including Inuit throat singing), it’s romantic, sensual, and throbbing with the kinetic energy of lovers and ancient sailing vessels—maybe even the whole universe. It’s painfully gorgeous; it goes into the body.

E – exil / exile

Barthes told Playboy, “One is never in love with anything but an image.” He’s not talking about pictures in a magazine; truly ravishing images, he argues, are “alive, in action.” Therefore, when a lover realizes fulfillment is impossible and gives up on his relationship, he isn’t giving up on a person per se but rather an image. And, in giving up on that image, he is also “exiling” himself from a language.

This, of course, is the province of popular music. Everyone recognizes “the love cry” à la declamatory songs like The Velvet Underground’s “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” and the “death of the image” à la soulful ballads like “No More I Love You’s.”

I – “I am crazy”

“In the field of my love,” Barthes proclaims, “I say yes to everything.”

Who else does this sound like? Wagner.

Nietzsche, who had an enormous influence on Barthes, called Wagner “the artist of decadence” and “a clever rattlesnake” to boot. In The Case of Wagner, he wrote, “Throughout his life [Wagner] rattled ‘resignation,’ ‘loyalty,’ and ‘purity’ about our ears, and he retired from the corrupt world with a song of praise to chastity! – And we believed it all!” Then he lambasts “Lohengrin” and other lionized Wagner operas for portraying a woman’s love as “no more than a refined form of parasitism.”

Of course, when Barthes declares, “I am crazy,” what he’s really admitting, with horror, is that he’s “mad to be in love.” A piece that beautifully conveys this idea is Billy Scott’s cover of “Nothing Compares 2 U.” Sinéad O’Connor made the Prince song famous, but Scott’s version is in a class of its own.

S – schema / scheme

Barthes insists I won’t fall in love with a man’s picture. I’ll fall in love with “a fragment of [his] behavior… the fugitive moment of an attitude, a posture… a scheme.” I’ll be attracted to the way his body moves.

It’ll feel like “Witchcraft.”

If I’m lucky, the relationship will lead me toward some “off-site Eden,” some neutral space par excellence (state of pleasure) where bliss (jouissance) is not what satisfies my desire but what “surprises, exceeds, disturbs, deflects it.”

A – absence / absence

Moreover, I’ll know I’m “in love” with a man when he’s gone and I’m waiting for him.

Werther, a recurring subject in A Lover’s Discourse, doesn’t exactly “wait”; after Charlotte turns him down, he decides to leave. Goethe’s Gretchen, on the other hand—to whom Barthes alludes but never mentions explicitly—faithfully sits and pines for her beloved Faust. In his lied “Gretchen am Spinnrade,” Schubert expresses Gretchen’s ordeal by mimicking the rhythms of her spinning wheel and giving voice to her anguish.

The lover who waits, Barthes concludes, is “like a package in some forgotten corner of a railway station.” The metaphor conjures Samuel Barber’s String Quartet in B Minor, which could be said to bleed vulnerability and heartache… from the package’s perspective.

S – “Special Days”

Borrowing from Lacan (with whom Barthes, in real life, underwent psychoanalysis to deal with heartbreak), Barthes affirms that “every meeting with the loved being” is “a festival.” The lover is like a little boy reuniting with his mother: Mommy, Mommy, Mommy, Mommy, Mommy, Mommy!

Schumann’s “Eintritt” (Entrance) from “Waldszenen” (Forest Scenes) sounds like a festival. It might depict an awaited moment: an affectionate first look at something. In Barthian parlance, it might also reflect “ars vivendi” (an art of living) “over the abyss” because subsequent movements of “Waldszenen” aren’t nearly as buoyant and playful. In fact, Clara Schumann found some later scenes—from “Verrufene Stelle” (Haunted Place), for example—too upsetting to play; on the printed score, her husband had copied down a poem by Christian Friedrich Hebbel that begins, “The flowers that grow so high here / Are pale, like death.”

As Gide observed, you can feel Schumann’s joy “coming between two sobs.”

K – Kierkegaard

Another Barthesian principle: every “exchange” between lover and beloved is a “scene,” which can be defined as the “exercise of a right, the practice of a language.” Scenes—or dialogues, euphemistically—never actually result in “enlightenment.” Nevertheless, lover and beloved vie for “the last word.”

Barthes compares this dialectic to “a perverse orgasm” and “the Roman style of vomiting.” I’m comparing it to the Mozart character from “Amadeus” laughing and the first movement of his String Quintet in G Minor.

Alluding to Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, Barthes also emphasizes the power of silence, which brings to mind Terry Riley’s “Captain Jack” from “Cadenza on the Night Plain.”

I – inconnaissable / unknowable

The lover is caught in a cycle of self-questioning: Why do I want to know him? What would it mean to know him? CAN I EVER REALLY KNOW HIM?

Barthes traverses intimacy—specifically, the lover’s efforts to know the beloved being precisely—with this proviso: “It is not true that the more you love, the better you understand.”

This calls to mind Missy Mazzoli’s chamber piece “Dark With Excessive Bright,” which she named after a phrase in Milton’s Paradise Lost. The phrase comes from the section in Book 3 where Milton, who is blind, discovers God in heaven:

Fountain of light, thy self invisible

Amidst the glorious brightness where though sit’st

Thron’d inaccessible, but when though shad’st

The full blaze of thy beams, and through a cloud

Drawn round about thee like a radiant Shrine

Dark with excessive bright thy skirts appear

In her program note, Mazzoli explains “dark with excessive bright” as not only “a surreal and evocative description of God,” but also “a strangely accurate way to describe the dark but heartrending sound of the double bass.”

True intimacy is always an illusion. Seeking it is pure religion.

N – non-will-to-possess

Non-will-to-possess means “I will not make any attempt to possess the other.” I will “imprison [I love you’s] behind my lips” and climb into “an unlabeled bed.”

In Barthes’s dramatization, such “withholding” is “an erotic principle of the Tao” and a form of benevolence (Agapé). This is a powerful idea, though it begs the question: How long can any lover manage it? Does neutrality finally become untenable? Every lover wants affirmation.

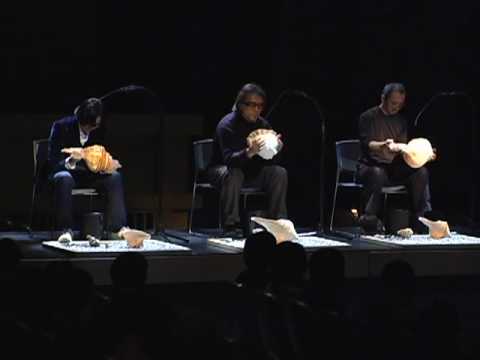

Ultimately, Barthes submits that successful couples balance “a little prohibition” with “a good deal of play,” designating desire and then leaving it alone. Depending on how you interpret this, you may end up in territory as divergent as John Cage’s “Inlets” or as well-furnished as Dvořák’s Bagatelles.

I want to say I lean toward Dvořák. Those conch shells though… Could they be the razor’s edge, a new conception of erotic “time”? ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.