I don’t know what’s more unforgivable: that conductor and long-serving Bard president Leon Botstein accepted money from Jeffrey Epstein, or that he put me in the position of agreeing with American conservative outrage-monger Dinesh D’Souza. “He is ideologically unpredictable, even eccentric,” D’Souza was quoted as saying of Botstein in a 1992 New York Times profile of the academic polymath. “That’s partly a function of intellectual suppleness and partly a function, I suppose, of incoherence.”

Last week, after a Wall Street Journal report revealed the numerous meetings Epstein took after his first stint in jail for having sex with a minor to include several with the president of Bard College (where he also oversees the annual Bard Music Festival and SummerScape programming), Botstein defended himself to both the Journal and in a follow-up interview with the New York Times for accepting two gifts from Epstein—an unsolicited $75,000 donation to the college, and 66 laptop computers.

“We had no idea, the public record had no indication, that he was anything more than an ordinary—if you could say such a thing—sex offender who had been convicted and went to jail,” Botstein told the Times last week, echoing a defense he gave to the same paper in 2019, shortly before Epstein’s death: “If you looked up Jeffrey Epstein online in 2012, you would see what we all saw… [he seemed] like an ex-con who had done well on Wall Street.” While Epstein did much to launder his digital image and manipulate search engine results following his release from prison in 2009, this ignorance defense ignores the fact that multiple women were, from the time of Epstein’s 2008 plea deal (in which he agreed to plead guilty at the state level to one count of soliciting prostitution and one count of soliciting prostitution from someone under the age of 18 in exchange for immunity at the federal level), fighting for prosecutors to hold him accountable.

Reading this, I was reminded of a scene from the film “Casablanca.” In response to an impromptu performance of the “Marseillaise” by many of the café’s staff and patrons, protesting the Nazi authorities in attendance, the corrupt Vichy police chief Louis shutters Rick’s Café Américain. When Humphrey Bogart’s Rick demands to know the reason, Louis shouts, “I’m shocked—shocked—to find that gambling’s going on in here.” As if on cue, a croupier walks up to Louis and hands him a fistful of bills—his winnings for the evening. “Oh, thank you very much,” Louis replies sotto voce, before continuing the clearout.

“Most higher education is so cluttered up with mediocre thinking and mediocre talk that it just clobbers the mind,” a 23-year-old Botstein told the New Yorker in 1972. “Thank God we can concentrate on creativity instead of nonsense.” With his more recent refusal to acknowledge the obvious truths about Epstein, painting himself and Bard as the victims of capitalism and comparing their acceptance of his donations to “a priest…giving communion to a convicted felon,” it’s clear we’ve pivoted to nonsense.

If you Googled Jeffrey Epstein in 2012, you would have likely come across a 2011 story in the New York Post, in which he said: “I’m not a sexual predator, I’m an ‘offender.’ It’s the difference between a murderer and a person who steals a bagel.” That Post story also noted that a New York judge had ruled Epstein a Level 3 sex offender—meaning that he was the highest risk for repeating his offense and was considered “a threat to public safety.” Even given the Post’s status as a conservative tabloid, those facts are easily verified.

Still too sensationalist? Fine. In 2011 the Times, in reporting on the London School of Economics’s financial relationship to the Qaddafi regime, also questioned Epstein’s post-prison philanthropic spree: “It seems unlikely that any British university would follow the example of Harvard, which accepted a $30 million donation from the financier Jeffrey Epstein, a registered sex-offender,” wrote D. D. Guttenplan, who also noted that “many politicians who had received donations from Mr. Epstein returned the funds.”

It’s true that Epstein’s is not the first unpleasant money that has circulated through Bard. Under Botstein’s presidency, Bard has accepted donations to endow faculty chairs in honor of both Alger Hiss (a State Department official and UN cofounder who was accused of spying for the Soviet Union during the 1930s) and Henry R. Luce (the ultra-conservative publisher of Time and Life magazines who had an outsized influence on Washington and advocated for American hegemony). In a final twist of irony, the professor who currently holds the Alger Hiss chair is the same man who accused Hiss of espionage. More recently, in 2006, Bard established a $2 million faculty chair for Jacob Neusner, a then-faculty member who opposed feminism and affirmative action and denied climate change. Criticized for these incongruities, Botstein told the Times in 1992: “People have so little tolerance for dissent. What happened to free thought? Individual ideas? What happened to Thoreau?” (I don’t know about the last question, but I’m willing to bet that he’s not in any of the laundry rooms on Bard’s campus.)

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

When the Times reported in 1991 about the movement within American colleges and universities to put more, and more explicit, restrictions on student-faculty relationships, Botstein acknowledged that there should be rules in place to prevent abuses of power. However, he also argued that legislating or banning relationships between students and professors went against the role of colleges to “protect diversity, dissent, and an implicit critique of bourgeois morality.” One year earlier, responding to student protests against allegations of sexual harassment and rape at both Simon’s Rock and Bard, he said: “There is always going to be some libidinal component if we achieve the close teaching and mentoring to which we aspire—particularly using the so-called Socratic method.”

Those protests began at Bard College at Simon’s Rock (an alternative high school program in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, that’s run by Bard) when groups of 10th and 11th-grade students confronted teachers, mostly in their offices, with allegations of inappropriate touching and sexual harassment. The group, dubbed the Defense Guard, said they viewed this unorthodox move as necessary because they did not trust the reporting systems the campus had in place. A year later, with the Defense Guard still fresh in the minds of many, protests moved to Bard’s Annandale-on-Hudson campus in neighboring upstate New York, following reports of a sexual assault case on campus. More than 40 students occupied Ludlow Hall, which houses the school’s administrative offices.

In an interview with the academic journal Lingua Franca (republished in Harper’s Magazine), Botstein explained the Defense Guard incident away. The report of an unwanted touch “was a crossing of cultural lines, Western/non-Western,” which led him to pivot to “the differences in patterns of ethnic and cultural behavior,” particularly as it came to one of his favorite bêtes noires, “the highly puritanical, extremely unexpressive, and cold American standard.” He compared the high school students’ actions at Simon’s Rock to those of fascists and Brownshirts. Botstein, who has familial ties to the Holocaust, has used this comparison more than once: The Huffington Post reports that, during a 2015 “open house” discussion about sexual assault on Bard’s campus, he told students: “You have to use common sense. A girl drinking a bottle of vodka and then going to a party is as wise as me walking into a Nuremberg Rally while wearing the yellow badge.”

To his credit, Botstein admitted that, in the case of student-faculty relationships, “there may be a power difference,” adding that it went both ways: “[In] the current climate a student can wield considerable power in the very act of making a public accusation.” I have to wonder how he feels about that quote 30 years later, especially in the wake of a 2020 lawsuit filed against Bard by percussion student Avalon Parker, who named the college as well as Botstein and former dean Michèle Dominy as defendants. Beginning in her freshman year at Bard in 2016, Packer alleges she was subject to more than three years of abuse by her teacher, Carlos Valdez, who “used the power and influence he had developed…to repeatedly assault her in his basement office during private music lessons.” Valdez allegedly told Packer that the administration would protect him if she told anyone of the abuse.

When Packer eventually made a complaint to the school’s Title IX office, Valdez was fired. During the course of that process, however, Packer learned that Valdez had been the subject of at least two prior Title IX complaints, including one in 2015 that concluded with the recommendation he be dismissed. Valdez appealed to Botstein and Dominy and was reinstated after he wrote a letter of apology and took an online sexual harassment course. He was allowed to keep teaching students one-on-one in his basement studio, which was described in the court filings as isolated and soundproof. Packer’s lawsuit, which cited the college’s “single continuing violation of Title IX,” was settled out of court in 2021.

Historically, Botstein has chafed against the administrative work and bureaucracy that it takes to run a school. In a 1993 panel organized by Harper’s called “New Rules About Sex on Campus,” he spoke wistfully of the film “Chariots of Fire,” in which Oxford professors poured sherry for undergraduates as they socialized in a common room. “That’s against the law today. Not possible. Forbidden. A certain sensibility has driven out conviviality.” He also waxed nostalgic for the original university system of the Middle Ages, one that was “immune from the severity of civil jurisdiction. There was to be a spirit of liberty and self-regulation—hence fraternities and other such developments. Now the rules the universities promulgate are more ferocious than those found in civil society,” he said, citing one of those rules as “the category of date rape.” (On that panel, Botstein did concede that, despite the “libidinal” aspect of the Socratic method, “a sexual relationship between a teacher and a student is, in fact, at odds with the task of teaching.”) What Botstein, a longtime proponent of abolishing high school and having students start college at 16, misses in this point is that the level of ferocity promulgated by universities is that way for a reason: Most student bodies at the university level are younger and less experienced than the rest of civil society. “Theory and research in adolescent development show that adolescents need more support, not less, if they are to find their way through the vexing personal, social and career-oriented challenges of adolescence,” wrote one Hofstra professor in response to a 1999 op-ed by Botstein reiterating this theory.

But let’s consider date rape. Despite Bard’s campus being closed for part of 2020 due to the pandemic, reopening for that year’s fall semester with some hybrid modalities, reports of rape on campus property steadily rose between 2019 and 2021. In 2015, the college faced scrutiny for a case that was reported to the Title IX office. Investigators for the school found that a male student, Sam Ketchum, had violated the school’s sexual harassment policy, but allowed him to remain on campus and take classes. When the woman who had filed the complaint against Ketchum (referred to pseudonymously as Alison in one news report) learned of this outcome, she attempted suicide. It wasn’t until this incident, which involved police and paramedics on campus, that the Dutchess County Sheriff’s department learned about Alison’s initial complaint against Ketchum. They arrested him on a felony rape charge approximately one month later.

For Botstein, students of his generation (who attended college in the 1960s) “accepted the idea that higher education was about trying on the clothes of adulthood, so they eagerly accepted responsibility for their actions.” What set them apart from the students he was encountering, nearly 20 years into his tenure at Bard, was that “today’s students believe they are not responsible; quite the opposite, they feel they are owed something—an entitlement to a reward from distress. And when they are hurt, they are more prone to call themselves victims.” What’s most striking about this is that accepting responsibility for his actions is exactly what Botstein seems to be shirking in his years-long victim narrative around Epstein. I have no doubt that the billionaire was, as Botstein put it to the Wall Street Journal, “odd and arrogant” and, in last week’s Times interview, “a monster.” He is, after all, Jeffrey fucking Epstein. But Botstein has been wearing the clothes of adulthood now for more than half a century, and his defense that “people don’t understand what [his] job is,” along with his complaint to the Times that it “is a humiliating experience to go back over and over and over” his dealings with Epstein, both come off as more than a little entitled.

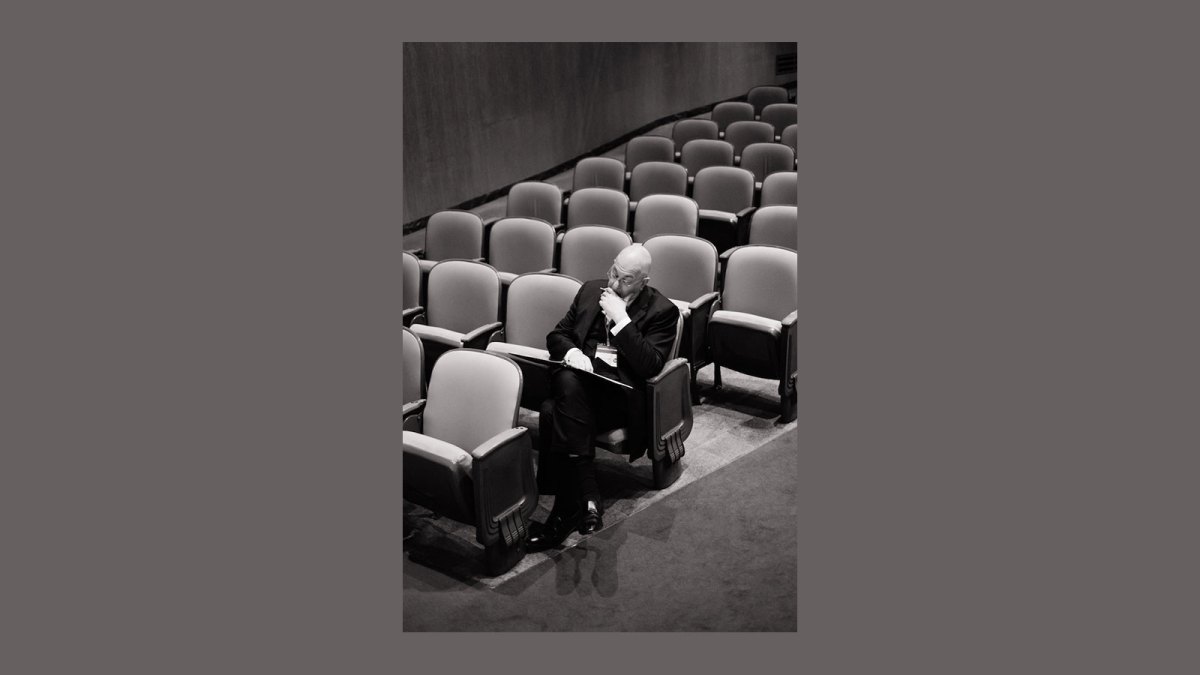

This, too, has been confirmed by colleagues. The late Joel Kovel, who started at Bard as an Alger Hiss Professor of Social Studies in 1988 and was dismissed from his faculty role in 2009, described “an overweening pride about the man and a sense of always being on stage that precludes ease in his presence.… He seemed, simply, irreplaceable and godlike on his small stage, his rule a bizarre admixture of an absolutist core and a liberal-progressive façade which would steadily disintegrate under its influence.”

According to Kovel, it was Botstein’s fundraising strategies—which favored a handful of hand-picked trustees and elite donors (a fact confirmed in a 2014 New Yorker article) versus sources that were “embedded in stable securities and regulated by internal control mechanisms”—that made the the rift in his leadership style more apparent. While he was “liberal-democratic” externally, Kovel argued, Botstein was “deeply reactionary, racist, and authoritarian in substance.” It’s not hard to see how his most recent defense of accepting Epstein’s money fits into that rift.

How much is $75,000 (plus 66 laptops) actually worth? It certainly pales in comparison to the millions Epstein donated to Harvard. Botstein may have been hoping to cultivate these two small donations into something bigger, but these pittances suggest that Epstein was merely looking to add one more .edu domain (which, in search engine optimization practices, often rank highly in search results due to the legitimacy they confer) to his rehabilitation project. What will last longer than any of the money that he gave to Bard is Botstein’s defense for accepting it. ¶

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Bard received two gifts from Jeffrey Epstein, one for $75,000 and another for $50,000, in keeping with a 2019 New York Times report. Epstein only donated $75,000 to Bard, as well as 66 laptop computers.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.