James Jorden, who died earlier this week at 69, is almost certainly one of the most influential people in my life who I never met. In 1994, frustrated with his own floundering career as a stage director, and by the sorry state of both opera writing (overly academic guff or reformatted press releases) and opera performance (snoozy, billionaire-funded walkthroughs of works that should be gutsy and bloody and bold), he started making a DIY zine called Parterre Box and distributing it at Tower Records and gonzo-style in the cruisy bathrooms of the Metropolitan Opera. Eventually the site moved online, where he broke stories and posted blind items as his drag persona La Cieca, and fostered a community where three generations of opera queens learned our aesthetic values and affective approach. As the site grew, Jorden kept taking chances on new writers and ideas, and gave older ones—like the feisty and impossible, but also impossibly-knowledgeable Albert Innaurato—chances to share what they knew with the youngsters.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Wayne Koestenbaum and Ethan Mordden both published books (respectively, The Queen’s Throat and Demented) that thematized gay fans’ participative contribution to operatic performance and appreciation practice. What Koestenbaum and Mordden had done in theory, Jorden put into action. Here was a zine, and then a website, dedicated to “remembering when opera was queer and dangerous and exciting and making it that way again.” The very first issue, four mimeographed pages of pasted-together clips, set the tone. On the left, campy humor: a joke about a Philip Glass bio-opera of Sunny von Bülow withdrawn because the composer found Kiri te Kanawa’s interpretation of the title role “too dull”; a joke about Jessye Norman playing Oprah Winfrey in a new opera about Amy Fisher (Cecilia Bartoli) and Joey Buttafuoco (Plácido Domingo); a joke about a Gian Carlo Menotti opera of “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” starring Leonie Rysanek and Christa Ludwig in Vienna and Fiorenza Cossotto and Montserrat Caballe at La Scala. (I’ll take a revival of that one starring Waltraud Meier and Karita Mattila, please!) Future such jokes would include a returning bit about an operatic adaptation of “Valley of the Dolls.” (My dream cast for today: Lisette Oropesa as Anne Welles, Latonia Moore as Neely O’Hara, Nadine Sierra as Jennifer North, Jonathan Tetelman as Tony Polar, and Ms. Mattila as Helen Lawson.)

But swirling around the camp humor in that first issue was a remarkable text, “I love my dead gay Walsung,” which evinces a directorial Konzept for the first act of “Die Walküre” that no director I’m aware of has yet been brave enough to run with. (Barrie Kosky, our nation turns its lonely eyes to you.) “I left home and I was attracted to guys and to girls but whatever it was I was looking for, friendship or sex, I always got fucked over,” reads the voice of Siegmund, the opera’s hero. “Daddy was telling stories and you were too excited to eat and Daddy was wearing a sword and you asked if you would ever have a sword and he said you will boy when you need one. Everyone was sleeping and Daddy asked if you were hungry and you and Daddy went hunting.” Retelling the story that occurs before the opera’s first act, when the twins are reunited, the text—really a poem—recounts the separation of Siegmund and Wotan as a gay S/M scene: “You were hungry and you smelled meat. After you saw her you searched for your sister…you cried. You didn’t want to go into the forest so you lay down and you cried and you slept and you rolled over and you reached out… you never saw your father again. Men wanted to hurt you and sometimes they hurt you and sometimes you didn’t mind. You found your sister. You got your sword. And you saw your father again. And you hoped he could see you were trying to smile because you wanted him to know you understood why he had to kill you. Because he’s not just your Daddy. He’s God.”

Woof. Queer and dangerous and exciting indeed. A tribute to Wagner’s perversion. A brave and original reading of Wagner’s text, and a remarkable bit of poetry on its own. This set the Parterre tone: campy jokes, bitchy humor, a hunger for the overwhelmed feeling that sets in when opera is firing on all cylinders. This is how I learned to love opera. Jorden’s model was mine as I became an opera queen. Opera deploys every technology of feeling to create maximum expression. When you know what it can do to you, you’re ready to do almost anything to get your fix. When you see the flaws in the way of it doing that—clueless directors, inadequate rehearsal, a singer who has no business in the role—that’s where the bitchy humor comes in.

The other option is to rage and rant about how No One Sings Well Anymore and You Think She’s Good, That Shows How Stupid YOU Are, You Need To Go Home Right Now And Listen To The Serbian Contralto Sjla Cszhcldzchzić, Now THAT’S What REAL Singing Is. There was always some of this on Parterre; Jorden never participated. His appreciation for dead singers and performers was only ever one part of a body of knowledge put to use to insist that opera mattered most in the room, in person, as live theater, as a voice traveling unamplified through space and touching you.

Parterre’s children live. In the 1990s, the New York Times and its classical music desk were frequent targets. Who were these “critics and their criticism” who knew nothing of the form and of its history, who wrote bland or overly academic or overly boosterist treatments of everything the Met did? Today Zachary Woolfe, certified Friend of the Box, is the chief critic at the Times desk, and published a lovely obituary of Jorden there the day after he died. This publication, and its insistence that this music matters now and we can talk about it like real people, were equally shaped by Parterre’s—by Jorden’s—point of view.

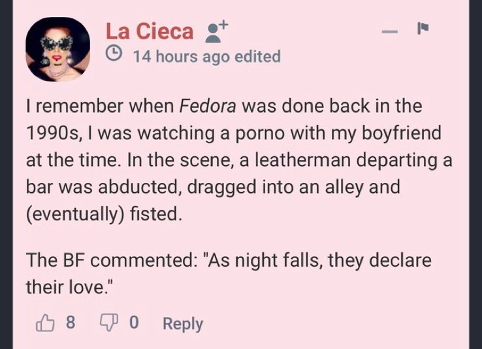

But the site itself remains essential. Where else, amid a comments section discussing the Met’s production of Giordano’s verismo potboiler “Fedora,” could you find historical reflections on the performance practice of Italian opera from multiple generations of queens, trenchant critiques and appreciation of the artists performing it live, and also the following comment from Jorden? I include it here to close because I can’t do any better:

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.