Early in Wagnerism: Art and Politics In the Shadow of Music, a history of the cult of fandom devoted to the operas of 19th-century German composer Richard Wagner, Alex Ross drops a charming anecdote from the 1850s. Poet and critic Auguste de Gasperini told of being “subjugated” by Wagner’s music, suffering what Ross calls “an unusually strong reaction to one of Wagner’s more innocuous pieces.” The passage that brought Gasperini to his knees was the wedding chorus from “Lohengrin,” known to most English-speakers, whether we care to know Wagner or not, as “Here Comes the Bride.”

Does anybody need more evidence that Wagner was an unstoppable Romantic/modern psy-ops mind-controller?

This story is only one among Ross’s hundreds of examples of Wagneriste passion and commentary. Permutations of fandom spread from opera into other art forms and communities; sparking, reinforcing, or countering aesthetic and political trends, arguments, and ecstasies. That influence started long before Wagner’s death in 1883. It has affected roughly 170 years of music, theater, visual art, literature, and film—as well as philosophical discourse, global politics, and warfare. Wagner’s spectre is present in imperialist Japan and both U.S. invasions of Iraq. Through the fandom of Theodor Herzl, he pops up in the founding of Zionism. He’s in the 20th-century resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan thanks to D.W. Griffiths’ film The Birth of a Nation. He’s there in both W.E.B. Du Bois’s formulation of double-consciousness and, just a few decades later, the Nuremberg rallies. His music was used in both Axis and Allied war propaganda, along with “Star Wars,” and, most ubiquitously and insidiously, all those weddings. (The next time I’m a bride, I’m gonna march to “Wehvolles Erbe, dem ich verfallen,” but it’s still, like turtles, Wagner all the way down.)

Of so much fandom, Ross writes:

You need not love Wagner or his music to register the staggering dimensions of the phenomenon. Even those who spend their lives studying the composer sometimes become exasperated or disgusted with him. As George Bernard Shaw said, in his classic study The Perfect Wagnerite: “To be devoted to Wagner merely as a dog is devoted to his master … is no true Wagnerism.” You can sympathize with Stéphane Mallarmé, who spoke of “le dieu Richard Wagner,” and also accept W. H. Auden’s description of the man as “an absolute shit.” Wagner’s divisiveness, his undiminished capacity to enrage and confuse, is part of his allure.

Wagner’s legacy is simultaneously inspiring and annihilating; in Ross’s gloss of über-fan Thomas Mann, he “offers a handle for his own exploitation.” Thus, Wagnerism is not a history of Wagner himself (although there’s ample biography and context), but of the efforts by his fans and detractors to find answers to some hard questions: Who’s subjugating who? Why do Wagner’s fans love him so, and why do they gotta be that way? How do we solve a problem like Wagner, and, perhaps most importantly, why do we keep trying?

Fans of Symbolist poetry and early Soviet filmmaking will have their favorite sections in this book. I particularly enjoyed the discussions of Joyce’s rioting with Wagner in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, and the aural landscape fantasias of Willa Cather (“Her achievement was to transpose Wagnerism into an earthier, more generous key,” writes Ross. “She offered grandeur without grandiosity, heroism without egoism, myth without mythology. Brünnhilde stays on her mountain crag, hailing the sun: no man breaks the ring of fire”). Ross breaks down barriers between purportedly literary art and fan art, citing some deliriously wonderful 19th-century actually-approved-by-a-real-editor Wagnerian literature that imagines sexy encounters with vampire ladies, useless men, corpses, and, most transgressively of all, with normal people but inside the sanctum of the Bayreuther Festspielhaus itself during a performance. (Also: Do not miss the stranger-than-fanfiction Wagneriste exploits of Maud Gonne.)

I had no beach reading this summer, because I did not go on a fucking beach vacation. Instead, I lay in my bathtub taking notes on Wagnerism, playing “Tristan” on Spotify, and hooting immoderately at all the subjugation jokes and fin-de-siècle Wagnerian esoterica. (Ross points to a bathtub sold by Moosdorf & Hochhäusler that allowed bathers to rock back and forth while singing ‘Wagalaweia!’” Believe you me, once I’m finished with this review and don’t need to worry about splashing my laptop, the Rhinetub and I are going places.) In fact, reading Wagnerism in the tub was all I did this summer, because I’m a slow reader, and this book is 664 pages long before the notes start. Truly true Wagnerians will enjoy the impressive bibliography, which cites some even more compendious tomes, Timothée Picard’s 2,496-page Dictionnaire encyclopédique Wagner (2010) among them. But Ross’s prose was good company: chatty and occasionally rollicking, but more often thoughtful, tender, and ethically urgent. By turns, the chapters felt like a syllabus-writing teacher filling in the gaps in my cultural knowledge and experience; a slightly breathless raconteur spouting gossip; at the very end, a delightfully self-deprecating personal essayist; and, often, a real geek, amassing the long, minutely detailed lists of arcane facts that nobody, except other opera fans, will appreciate. (These are the kinds of people I hung out with on beaches, back when we had beaches.)

That effect is twofold: All fans, in any fandom, enjoy obsessive list-making. We like collecting things, and we like our mastery of vocabularies and experiences. If we’re social rather than solitary fans, we like sharing them with Opera Twitter or even (gulp) with real live people. (The night that Waltraud Meier stepped in to sing Isolde at the Met, OMG! Were you there? Do you see it, friends? Do I alone hear this melody, which wonderfully and softly, lamenting delight, telling it all, mildly reconciling sounds out of him, invades me, swings up, sweetly resonating rings around me?!?!?!??!?!) Reading a book you enjoy creates a hail-fellow-well-met feeling of congeniality and conversation. Amplified by fandom, it feels like belonging to a community.

On the other hand, I couldn’t say how Wagnerism might come off to someone who couldn’t keep Fafner, Pogner, and Heinrich der Schreiber straight, let alone scan the opening bars of “Rheingold” at the start of Chapter 1 and thrill, deep in her guts, at the sight of all those sustained E-flats. (Or of Ross’s reading: “Then eight horns enter one after another, in upward- wheeling patterns, which resemble the natural harmonic series generated by a vibrating string. Other instruments add their voices, in gradually quickening pulses. As the mass of sound gathers and swirls and billows in the air, the underlying tonality of E- flat does not budge.” Wagalaweia!) But Ross is a storyteller, and if the lists are sometimes exhaustive to the point of, well, exhaustion, their amassing serves the purposes of argument, crafting stories of operas, aesthetic movements, and geographic and cultural continuities and disjunctures. The non-Wagnerian might very well find that Wagnerism enhances their appreciation for Philip K. Dick (huge fan of Wagner) or Virginia Woolf (ambivalent fan of Wagner). What’s more, it’s enjoyable to read these other artworks through Wagner, rather than focusing exclusively on Wagner.

Finally, Ross is enacting the performance of fandom itself, full of generosity, enthusiasm, and hospitality. He wants to introduce us to his passion, his knowledge, and his community: the living one, and the generations of fans who’ve preceded us.

Speaking of which, my other favorite thread in the book was the history of “Ride of the Valkyries” as a soundtrack for aerial warfare, from, incredibly, Marcel Proust—“One had to ask oneself whether they were indeed pilots and not Valkyries who were sailing upwards …That’s it, the music of the sirens was a ‘Ride of the Valkyries’!”—to Arturo Toscanini (whose WWII concerts expressed Allied hopes of bombing Germany into smithereens) to “Apocalypse Now” and beyond:

Apocalypse Now captures an empire in its decadence, to adapt a phrase from Paul Verlaine.… Yet the film’s virtuosity blunts its own critique. Apocalypse soon became a military fetish object, and its Wagner scene influenced real-life behavior. Black Hawk helicopters blared the “Ride” during the American invasion of Grenada in 1983. In 1991, a psy-ops unit played it at the Battle of 73 Easting, in the Iraqi desert, during the First Gulf War. Loudspeakers mounted on Humvees boomed out the “Ride” at Fallujah in 2004, during the second American invasion of Iraq.

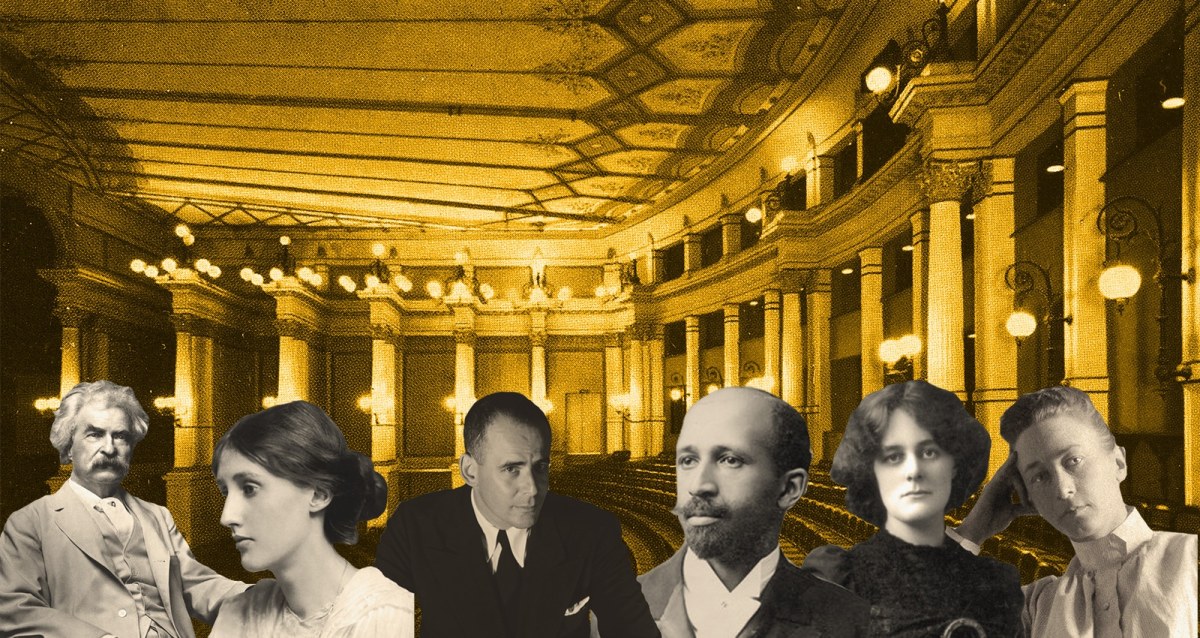

When we join the community of fans, we sit in Bayreuth’s merciless wooden seats beside Mark Twain, Woolf, Lincoln Kirstein, and the architects of war.

There’s a whole body of criticism devoted solely to the subject of Wagner and Hitler, and much of Ross’s book grapples with Wagner’s antisemitism and its cultural influence before, during, and after WWII. Ross quotes Pascal Quignard’s formulation of Walter Benjamin: “I am surprised that people are surprised that those among them who love the most refined and complex music, who are capable of crying while listening to it, are at the same time capable of ferocity. Art is not the opposite of barbarity. Reason is not the contradiction of violence.” From the start, Ross is clear that “Emphasis on ‘Hitler’s Wagner’ in recent decades has been a necessary corrective to the silence that Wagnerites long maintained, whether because of lingering Nazi sympathies or because of a simple wish to avoid the subject.”

In a book teeming with arguments against simplicity and reductive thought, and for ethical complexity and nuance, does the suggestion that the wish to avoid this topic could be “simple” not illustrate the irreducible problem of art and fascism? Simple for whom, and how? The word “simple,” in a book arguing so strenuously for its opposite, shows the urgency for our continued, obsessive, unending revision of our own cultural commentary. It demonstrates why for 170 years people have been fighting about Wagner: In the face of fascism, all our words, art, and criticism matter so much, launching powerful consequences beyond our control—and yet matter not at all—and yet are all we have. Words and art fail us. The art of ethical criticism requires its own undoing, over and over.

I’m almost entirely 99 percent persuaded by the elegance and conviction of Ross’s long game: his attention to fans, critics, and thinkers who, from the very start of Wagnerism, resisted the seduction of easy answers. There’s Nietzsche, once the world’s greatest Wagner fan, then the world’s greatest Wagner hater, who raised early concerns that Wagner’s antisemitism, nationalism, and triumphalism boded ill for opera and, basically, the whole world. There’s Theodor Adorno (“Redemption, in Wagner, is tantamount to annihilation: Kundry is redeemed the same way in which the Gestapo may claim to have redeemed the Jews”) who also, somehow, insisted on the doubleness of that “redemption,” believing that the decadence, vulnerability, imperfection, and dissolution in Wagner’s forms suggested a simultaneous destabilization of the annihilating order. In his gorgeously written and conceived conclusion, which I want to quote in full, Ross says:

In the story of Wagner and Wagnerism, we see both the highest and the lowest impulses of humanity entangled. It is the triumph of art over reality and the triumph of reality over art; it is a tragedy of flaws set so deep that after two centuries they still infuriate us as if the man were in the room. To blame Wagner for the horrors committed in his wake is an inadequate response to historical complexity: it lets the rest of civilization off the hook. At the same time, to exonerate him is to ignore his insidious ramifications. It is no longer possible to idealize Wagner: the ugliness of his racism means that posterity’s picture of him will always be cracked down the middle. In the end, the lack of a tidy moral resolution should make us more honest about the role that art plays in the world. In Wagner’s vicinity, the fantasy of artistic autonomy falls to pieces and the cult of genius comes undone. Amid the wreckage, though, the artist is liberated from the mystification of “great art.” He becomes something moreunstable, fragile, and mutable. Incomplete in himself, he requires the mostactive and critical kind of listening.So it goes with all art that endures: it is never a matter of beauty proving eternal. When we look at Wagner, we are gazing into a magnifying mirror of the soul of the human species. What we hate in it, we hate in ourselves; what we love in it, we love in ourselves also. In the distance we may catch glimpses of some higher realm, some glimmering temple, some ecstasy of knowledge and compassion. But it is only a shadow on the wall, an echo from the pit. The vision fades, the curtain falls, and we shuffle back in silence to the world as it is.

I love that.

Ross’s thinking, like Adorno’s, is incredibly moving and persuasive to me; it accords strongly with my own response to and growth with Wagner. It looks conclusive, but it’s not. Who are “we,” who see reflections of ourselves in Wagner, for good or for bad? Some of us are more likely to be crushed by fascism and its influence in arts and politics. Some of us are more likely to collude, and benefit from it. And those of us who engage with, comment on, and, in turn, promote Wagner, need to question the ethical certainties of our own uncertainty.

Like Adorno, Ross, and basically all Jewish and Black Wagner fans, I want to believe that the clear-eyed, judicious assessment of Wagner’s failings can preserve a space for my own private mediation of ethics and emotion. I want to navigate them with the certainty that there is no such thing as rightness or certainty, looking at the operas, like Ross citing Alain Badiou, “as a heterogeneous, open-ended, future-oriented body of work,” acknowledging the complexity of having no easy, simple answers.

But I can’t stop thinking about how violent abusers, when confronted with accusations and charges, will whine, “But the situation was so much more complicated than that. It’s not so simple. I’m not a bad person: I’m a complex human being with flaws.” Their appeal not to be reduced to monsters, to have their complicated humanity honored, is just. But it’s also an excuse and an opportunity for them to win and weaponize empathy, to crush the dignity and humanity of their victims.

In the very humane, reasonable, just invocation of ethical complexity, we also tell ourselves lies. Necessary lies, maybe, that allow us to keep a measure of faith and conviction—the will to resistance—in a world whose simplest certainties are also often bigoted, violent, murderous, and genocidal. Complexity is our weapon against those simplicities, but it’s double-edged. Both the illusion of ethical certainty—and also the illusion of open-ended, future-oriented, heterogeneous, individually subjective, ethically uncertain but right engagement—are at best tropes we can never rest with; at worst, the sophisticated excuses we frame, and believe in—as we nevertheless should—while the neo-Nazis gather outside.

Hi, my name is Alison, and I love Wagner. That probably makes me a bad person. And I know that. But I’m not going to stop. On the contrary, I’m going to declare that Wagner is SUPER PROBLEMATIC, because I’m totally OK with playing this game of chicken with my own moral turpitude, so long as I keep getting tickets to Bayreuth and everybody knows I’m one of the Good Fans.

What I love best about Wagnerism is Ross’s effort to show the teeming floods of fans and their different fandoms, their efforts to grapple with these matters—and their failures—and their adaptations of other failures, and other successes—and above all, the creation, dissolution, and re-creation of communities around the art. That, ultimately, is why he gives us this flood of stories, lives, artworks, anecdotes, conflicts, and creations: to show us not Wagner’s triumphs and failures, but those of our living, ongoing world of culture and belief, breathing, trying, failing, trying again. Singing. And killing. And trying to do a hell of a lot better than that.

We can only, ever, keep trying to form new, better communities—in the opera world, and outside. In the breadth, compassion, humor, and critical rigor of this book—and even in my minor quarrels with it, which are conversations, opportunities, engagements—Ross recognizes, and reshapes, the world of Wagnerism as it is, for good and for bad, and makes room for the inadequacy of all our cultural criticism—along with its urgency. Although he closes with shadows, faded vision, and the silent return to the world as it is, I can’t help but think that precisely in that pessimism—or, if you will, realism—subsists the “ecstasy of knowledge and compassion.” That recognition of the violent, terrible facts of our world, and of ourselves—and the silence, the resignation, the dullness, the despair—is also what empowers us to keep reforming our communities, to reach out to each other, in love and care and music and beauty, to keep trying for the glimmering higher realm, as though we believed a better future were possible. That belief is possibility. In that belief, the possible is. ¶

Comments are closed.