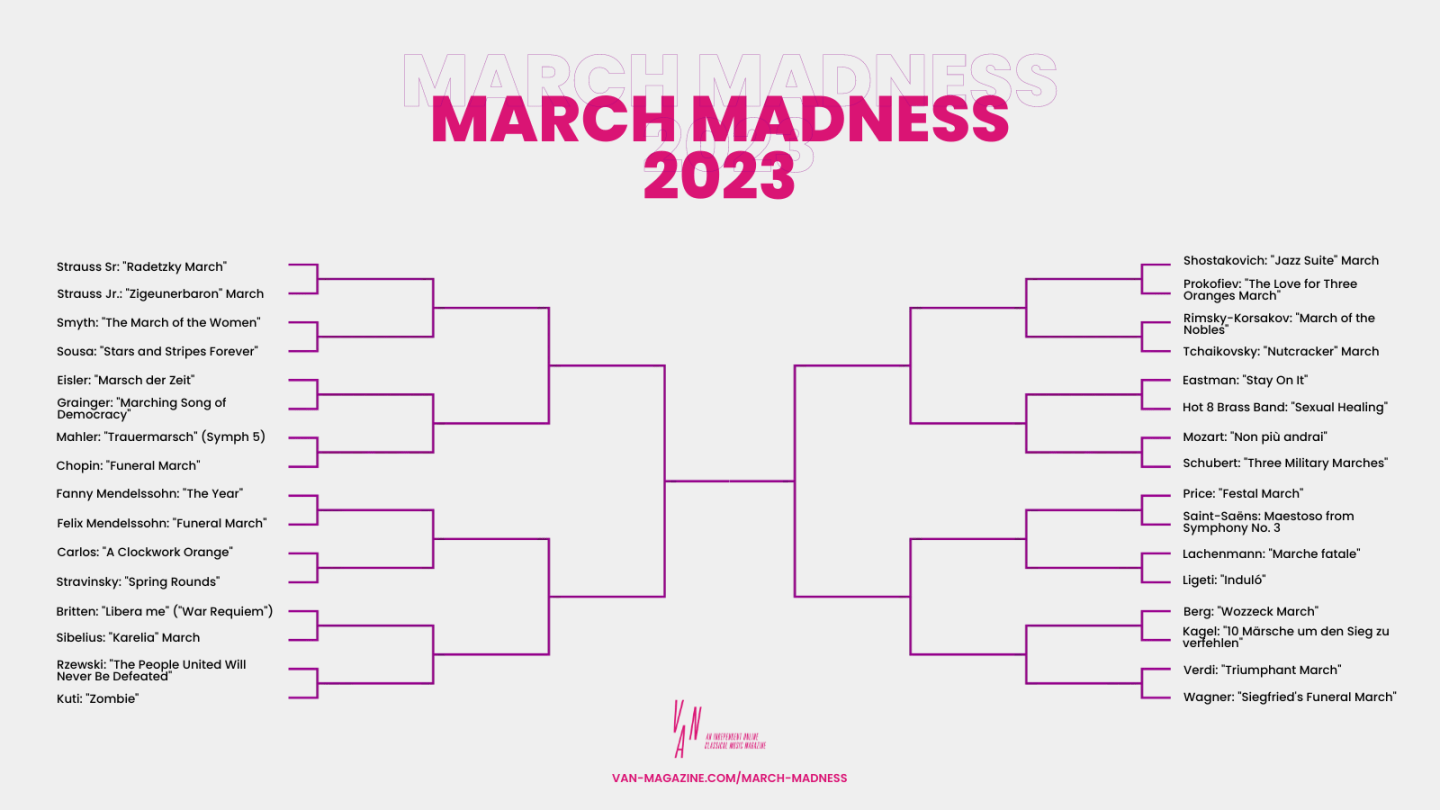

“What if we did a playlist of 32 musical marches to tie in with March Madness?” asked one VAN editor who definitely understands sportsball and did not have to google how many teams are in a bracket (or when March Madness takes place).

As classical-music-cartoonish as the idea sounded, it did get us thinking about the genre. What, exactly, defines a march? Grove cites “strong repetitive rhythms” and “an uncomplicated style,” adding that they’re most often used for military movements. But that’s a bit limiting, especially when you think of the multiverse of marches used to accompany funerals, weddings, protests, and DCI competitions.

With that in mind, the VAN English team has put together a bracket that broadly explores the march as a musical mechanism, with each of the 32 works having their own form of march-y elements. We’ll update the bracket throughout the month on Twitter as you, dear reader, help us vote on one march to rule them all (we’ve made the case for some of our particular favorites below). If you’ve already left Elon Musk’s dumpster fire, the bracket is still arranged in a way that makes for some good comparative listening. Take, for instance, two sides of the protest march in Frederic Rzewski’s “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” and Fela Kuti’s searing commentary on the Nigerian army, “Zombie.” Or the pairing of organ processions in Florence Price’s “Festal March” against its much more dressed-up cousin, the final movement of Saint-Saëns’s “Organ” Symphony.

Johann Strauss, Sr.: “Radetzky March” (1848)

Johann Strauss, Jr.: March from “Der Zigeunerbaron” (1885)

Those of you who object to the racist undertones of Strauss Jr.’s work will hear no argument from me on this. Berlin’s Komische Oper—which, under the direction of Barrie Kosky, became a house dedicated to the golden age of operetta—has likewise grappled with this problem child of the art form (one of many). In the program notes for Tobias Kratzer’s 2021 production, the Komische Oper points out that the German version of the slur Zigeuner has an especially loaded legacy in Germany due to the stigmatization of Romani and Sinti people under National Socialism and “rightfully shouldn’t be used in the language of today without context or commentary.” A commentary that Kratzer wove into his retooled and recontextualizing libretto: “I suppose you want to take my ‘gypsy schnitzel,’ too?!” demands the character Count Homonay at the beginning of the work.

Indeed, the conflict of context becomes one of the central themes in Kratzer’s “‘Zigeuner’baron,” making the old-fashioned, Von Trapp-ings of the warhorse into an acutely relevant conversation today. The third act march, featuring the victorious return of the Austrian army, is underscored by the fact that our heroes only won thanks to the participation of the communities the Austrians had marginalized. It becomes a funhouse mirror held up to Strauss Senior’s “Radetzky March,” and closes out the production, moving from live orchestra to an old phonograph. Faced with the reconciliation of history and his own complicity in enforcing a shitty status quo, Count Homonay removes the record from its gramophone and smashes it to bits.—Olivia Giovetti

Ethel Smyth: “The March of the Women” (1910)

On a gray day in March 1930, Ethel Smyth donned her doctoral robe and cap and stood outside Parliament to conduct a suffrage anthem with a group of diametrically opposed musicians. By the time Smyth was performing “The March of the Women” with the Metropolitan Police Band, the piece was already a feminist classic, as the rallying song of the Women’s Social and Political Union. As Leah Broad notes in her recent book “Quartet,” composing the “March” was the first trenchantly suffragette act of Smyth’s career, and she would later take the march to Holloway prison, conducting a rousing rendition for other inmates, using a toothbrush dangled out of her cell window as a makeshift conducting baton.—Hugh Morris

John Philip Sousa: “The Stars and Stripes Forever” (1896)

I grew up playing dour, tricky British brass band marches: the lumbering, menacing, solid sort, with names like “Knight Templar” and “Death or Glory.” By contrast, John Philip Sousa’s march “The Stars and Stripes Forever” announces itself with two toots and a twirl.

That America’s national march had a double life as a sarcastic soccer chant only widens the schism between the earnest patriotism of its intentions and the intensely silly nature of its outcome. And from the Viennese twiddles, to the spluttering bass subject, to its ludicrous piccolo solo in the trio section, everything Sousa touches turns to camp.—HM

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Hanns Eisler: “Marsch der Zeit” (1957)

Composed to a poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky, “Marsch der Zeit” (“The March of Time”) by Hanns Eisler seems most likely to be sung by the sort of improbably hot proletariat farmers beloved by Social Realist propaganda-poster artists. Musically, the piece doesn’t transcend most marches by the capitalist pigs. But the YouTube comments section on the video have proven a fertile ground for debating the good sides of Stalin’s legacy.—Jeffrey Arlo Brown

Alban Berg: “Wozzeck,” Act I, Scene 3 (1922)

The latent violence and ugliness of the military march are everywhere in this section of “Wozzeck”—except in the text; Marie sings that “soldiers are beautiful people” as the march lurches down the street like a drunk, reeking, entitled officer. Rarely has music been used with such devastating effectiveness to show the mismatch between ideal and reality.—JAB

Gustav Mahler: “Trauermarsch” from Symphony No. 5 (1902)

Frédéric Chopin: Piano Sonata No. 2 in Bb minor, “Funeral March” (1839)

Fanny Mendelssohn: March from “Das Jahr” (1841)

Felix Mendelssohn: Funeral March from “Lieder ohne Worte” (1843)

As the old saying goes, anything’s march if you’re brave enough, which firmly applies to this from the fifth book of Felix Mendelssohn’s piano collection “Lieder ohne Worte.” Here, Mendelssohn’s music is given the full symphonic wind band treatment, turning a lachrymose into an ebullient procession. It featured in the final procession of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral, its distinctly Wagnerian opening leaving many British commentators red-faced. But with the full weight of a wind band, it sounds less Wagner and more like one of Gustav Mahler’s extended symphonic excursions.—HM

Wendy Carlos: “A Clockwork Orange” (1972)

Igor Stravinsky: “Spring Rounds” from “The Rite of Spring” (1913)

Benjamin Britten: “Libera me” from “War Requiem” (1962)

I sang in Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” last spring in London. The “Libera me” is a march through the land of the dead. In rehearsal, we were told that the first choral entries are those of souls trapped in limbo, shadowed by sepulchral double basses. The soprano entry, low in their voices, is especially wan.

The piece stirs into its eerie half-life with solo percussion: bass, tenor, and then snare drum, which don’t stop playing until a devastating climax. I stood above the battery of drums in the performance; that moment remains one of the loudest things I have ever experienced.

Where do we march? To the underworld: It segues into Britten’s setting of Wilfred Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” where the souls of two enemy soldiers, baritone and tenor, meet in hell.—Benjamin Poore

Jean Sibelius: “Alla Marcia” from “Karelia Suite” (1893)

Frederic Rzewski: “The People United Will Never Be Defeated!” (1975)

Fela Kuti: “Zombie” (1977)

Dmitri Shostakovich: March from “Jazz Suite No. 2” (1938)

Sergei Prokofiev: March from “The Love for Three Oranges” (1921)

Inspired by symbolist theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold’s translation of 18th century playwright Carlo Gozzi’s play of the same name, Prokofiev’s “The Love for Three Oranges” is a meet-weird between constructivism and commedia dell’arte. Nowhere does this union become more perfect than in the march theme that occurs three times throughout the work. At times acerbic, at times akimbo, it’s a deliciously weird, tongue-in-cheek commentary on some of the main impulses behind royal military marches. Fitting, too, as Meyerhold would meet his end in 1940 during Stalin’s Great Purge.—OG

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: “Procession of the Nobles” from “Mlada” (1889–1890)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: March from “The Nutcracker” (1892)

Julius Eastman: “Stay On It” (1973)

“Players may choose to play and repeat the layered cells at their own discretion,” Julius Eastman writes in his introduction to “Stay On It,” adding: “Each element (Theme, Cells) may be repeated ad lib. Cues to move to each next section may be visual, or a predetermined musical cue.” With so much room for interpretation, the capaciousness of Eastman’s score seems at odds with many of the qualities associated with the march—chief among them unison and conformity. But marches are also the chance to lend full-throated voice to some of our most alkaline emotions, and those are the sort that burn like a magnesium coil at the heart of Eastman’s music. In this Wild Up rendition of the composer’s 1973 work, the rapture is palpably addictive.—OG

Marvin Gaye (arr. Hot 8 Brass Band): “Sexual Healing” (2007)

Ok, so we’ve already established that marches come at all kinds of tempos, but what about temperatures?

The heat is on with the Hot 8 Brass Band performing Marvin Gaye, a reworking right from the heart of a social tradition. New Orleans second line is world-beating, an essential part of Mardi Gras celebrations, and the driving force of long, snaking funeral processions. New Orleans-style brass bands are their own beast, with a backline of split percussion and sousaphone, and a fierce horn section up front. With a collective group swagger to boot, it’s a slow-marching brass juggernaut.—HM

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Non più andrai” from “Le nozze di Figaro” (1786)

Franz Schubert: “Three Military Marches” (1812–1824)

Leave it to Schubert to add a dash of subtlety, even melancholy, to a set of military marches. The “Three Military Marches” aren’t exactly the Piano Sonata in A Major D. 959, but they do have Schubert’s characteristic grace, levity, and elegance in their DNA. This music has the same sort of detached ironic distance to the army as the military scenes in Robert Musil’s satire from the twilight of the Austrian empire, “The Man Without Qualities.”—JAB

Florence Price: “Festal March” (undated)

Camille Saint-Saëns: “Maestoso” from Symphony No. 3 (1886)

Helmut Lachenmann: “Marche Fatale” (2020)

“Is a march, with its forcing of the collective into a martial or celebratory mood, a priori ridiculous?” asks Lachenmann. “Is it even ‘music?’ Can one march and listen at the same time?” In his “Marche Fatale,” Germany’s most essential—and most radical—avant-garde composer writes the only kind of march possible for the current state of civilization, which is to say a march straight to hell.—JAB

György Ligeti: “Induló” (1942)

Hector Berlioz: “Rákóczi March” from “La damnation de Faust” (1846)

If you ask me, the scene where Berlioz’s Faust and Mephistopheles enter the city where Marguerite lives—to the bilingual chorus of Francophone soldiers and Latinist students (“Villes entourées de murs et remparts”/ “Jam nox stellata velamina pandit”) is the more compelling of the marches in “Damnation.” But I’ve always maintained that more marches would benefit from lyrics in dead languages. That said, the literal march in this opera is also a wonderfully moody beast. Based on a folk tune lamenting Habsburg rule of the Magyar people, Berlioz’s adaptation was originally composed for a concert in Budapest but fits the inherent futility and fatalism of the Faust legend to a T.—OG

Giuseppe Verdi: “Triumphal March” from “Aida” (1871)

Richard Wagner: “Trauermarsch” from “Götterdämmerung” (1876)

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.